The hard work of growing up is never done. Every couple of years, I run headlong into a wall and realize I feel 15 all over again, all false bravado masking shaken confidence.

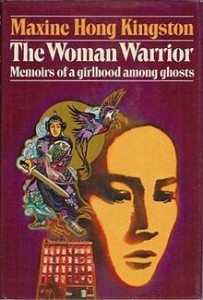

I was well into my adulthood when I read The Woman Warrior by Maxine Hong Kingston. The courage of her voice resounds like a gong throughout each chapter, speaking for generations of women who have been used, disregarded, discarded. After a life of fighting for a place at the table, she gives voice to her struggles and reveals the ancient truth: the one who tells the story sets the goddamn table.

If I had read this book as a nascent feminist in college, I might not have seen past the mettle in her stories to the deeper layers underneath. This past that weighs on her, seeks to dictate and define her, this very past is what she willingly carves on her back, not as martyr or slave but as witness. “The reporting is the vengeance—not the beheading, not the gutting, but the words.”

And so, what really draws me in is the deeper siren song of a woman unwilling to distance herself from the ghosts of her past in order to project her own true voice. Suddenly, living in a liberated present laden with the oppression that produced it is not something to go to therapy for.

I spent much of my early adulthood trying to outrun the influence of my religious fundamentalist upbringing. I tried to blaze my own trails, to disregard my agitation at leaving the fold. “Someday I’ll deal with this,” I’d think, building the wall higher and puzzling at my inability to remember details about my childhood.

The Woman Warrior showed me that I didn’t need to outrun anything, that it is okay to live with the ghosts. What fun is exorcising them when they animate the marrow of my own story? I had been running from the very thing that fueled my identity. A wall was scaled in learning to honor the grievances written on my own back.