Mightier Than the Sword

A celebrated cartoonist looks back on his singular life and career

Profusely Illustrated: A Memoir by Edward Sorel; Knopf, 227 pp., $30

Edward Sorel’s Profusely Illustrated manages to fuse art and autobiography with an unusual warmth and panache. Meant to be a “portfolio” of his best illustrations, cartoons, caricatures, and magazine covers, it also describes his “remarkably unremarkable life.” He tells us that “this book is essentially an attempt to save a few of my drawings from the oblivion that is the usual fate of ephemeral magazine art.” But Sorel is much too modest about his accomplishments. Over the past 60 years or so, he has given us some of the most original, biting, funny, and disturbing caricatures that anyone in this country has ever produced.

Born Edward Schwartz in 1929, he grew up in a tenement in the heartland of the Bronx, among the poorest of the poor. His Romanian mother had arrived at Ellis Island in 1923, as a girl of 16, just weeks before America’s prohibitive immigration laws took effect, restricting entry for Eastern European Jews. Her name was Rebecca Kleinberg, and we only glimpse her rare beauty on the last page of the memoir, where she poses with her own mother and four sisters—tall, dark haired, and dark eyed, she stares defiantly into the merciless eye of the camera.

Edward adored his mother and despised his father. He was baffled at why the elegant Rebecca would ever have married jug-eared Morris Schwartz, who was “stupid, insensitive, grouchy” and “made slurping sounds when he ate soup.” But there was a sly story hidden in their romance. Shortly after Rebecca came to America, she met Morris at the ladies’ hat factory where she worked. Morris lent her a nickel for lunch on her first day and invited her to the automat. Soon they began “keeping company.” Her mother and four sisters advised Rebecca against marrying such a boorish man. But Morris told Rebecca that “he would kill himself if [she] didn’t marry him”—a lament that must have moved her.

When Edward was eight, he contracted pneumonia and was bedridden for months. Having nothing to do, he started to draw pictures on the pieces of cardboard that came back from the laundry with his father’s shirts. Thus his life in art began. He attended Manhattan’s High School of Music and Art and also studied at Cooper Union, where he had to remind himself “how much I used to enjoy drawing—before I went to art school.”

He was essentially self-taught, and whatever talent he had grew out of that same bedridden boy. Edward, who still despised his father, legally changed his last name from Schwartz to Sorel “the moment—the second—I got a steady job.” He was inspired by Julien Sorel, the poor boy from the provinces in Stendhal’s novel The Red and the Black who sets out to conquer Paris. Edward Sorel was another poor boy from the provinces, and in his own way, he did manage to conquer New York.

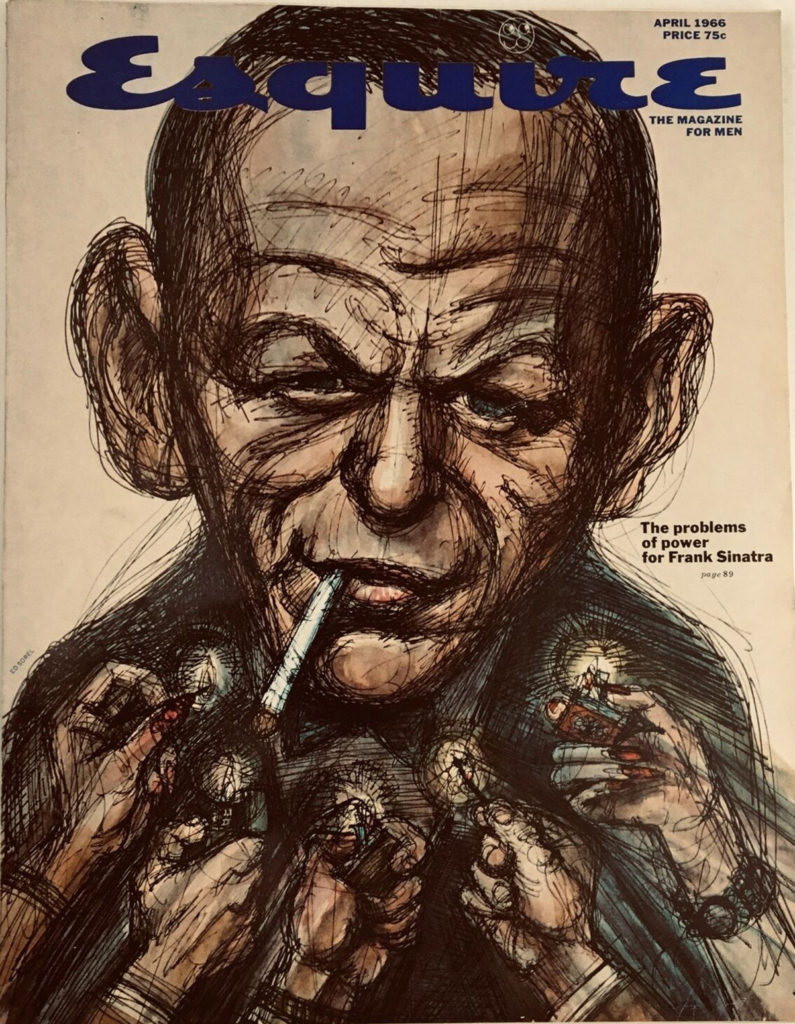

In 1954, he helped start Push Pin Studios with two of his former classmates at Cooper Union, Milton Glaser and Seymour Chwast. Push Pin, with its own jazzy style, would become one of the most influential graphic design groups of the latter half of the 20th century. Edward left Push Pin in 1957 and has been a freelancer ever since. He began designing book covers at $125 a clip and doing illustrations for magazines. His first real success came in 1966, when he was assigned to do the cover of Esquire magazine, accompanying Gay Talese’s celebrated profile of Frank Sinatra, called “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold.”

Sorel captures in his portrait some of the disdain and elusiveness of Old Blue Eyes. Sinatra has big ears, one blue eye (the other eye remains in the shadows), and a cigarette dangling from his lips, with five inked hands reaching out from the depths of the cover like claws clutching matches and cigarette lighters to serve him. No one else but Sorel could have caught Sinatra’s sad reign—and isolation—as king of the crooners.

Sorel would go on to do more than 40 covers for The New Yorker, perhaps the best of which is a caricature of Whistler’s Mother glancing with such scorn at the modernity of a white telephone beside her chair. He has also written and illustrated several children’s books; one of them, The Saturday Kid (2000), summons up much of his own childhood. Leo, the young hero of the novel, lives with his mother in the Bronx. The one thing that really excites him is the Saturday matinee at the local movie house, “where they showed cartoons, newsreels, a Dick Tracy serial, a Laurel and Hardy short, and two main features.” I suspect that the Saturday matinee, with its endless dance of faces, was the greatest pleasure Sorel had as a child and inspired much of his later work—its freedom, its perversity, its celebration of pure play.

I’m also a “Saturday Kid.” I grew up in the poorest heartland of the Bronx nearly a decade after Sorel. I, too, had a beautiful, elegant mother (from Belorussia rather than Romania) and a jug-eared father. Like Sorel, “I wished he would just somehow disappear.” And I sat through countless Saturday matinees, with a wonderland of images and the deep desire that each matinee would never end.

Hollywood was my second family, as it was Sorel’s. We both fell in love with an array of supporting characters because they could pop up anywhere, in any film. His favorites were Donald Meek, ZaSu Pitts, and Mischa Auer. Mine were Sidney Greenstreet, Cuddles Sakall, and Elisha Cook Jr. That’s how Sorel’s sense of caricature began. At the movies.

Later, his cartoons grew more and more political. He lampooned president after president with a marvelous originality and verve, showing us Nixon dancing the tango with Chairman Mao, Jimmy Carter as Gary Cooper in High Noon, or Barack Obama as Gulliver tied down by all the right-wing Lilliputians around him. As an “old lefty,” Sorel tried to weave presidential politics into the warp of his own political life. He reveals how America’s overthrow of Mohammad Mosaddegh in Iran and Salvador Allende in Chile, along with our disastrous attempts at “nation building” in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan, helped plunge us into the “oligarchy” of Donald Trump. It’s a pity that Sorel “lost interest in doing political protest drawings” a little before Trump came into power, or else we might have seen a caricature of Trump dancing with “Moscow” Mitch McConnell or crouching on top of the Capitol dome like some colossus in an orange wig.

Still, Profusely Illustrated is a pip of a book.