Milton Friedman’s Misadventures in China

The stubborn advocate of free markets tangles with the ideologues of a state-run economy

On a hot June day in 1989, the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party listened in stony silence as the most powerful leaders in Beijing denounced him. Just weeks earlier, as the world watched in horror, China’s rulers had turned their troops against the student protesters massed in Tiananmen Square—violence that General Secretary Zhao Ziyang, a steadfast reformer, had opposed.

“[You were] attempting to topple the Communist Party and wreaking havoc with the socialist system in coordination with hostile powers at home and abroad,” accused one wizened party elder. Another conservative piled on: “Our party and people have paid a price in blood for Zhao Ziyang’s serious mistakes.” Zhao, with his graying crown of swept-back hair, spoke up in his own defense, but his fate had been determined. He was dismissed as the party’s general secretary and placed under house arrest, where he would remain until his death in 2005.

A few days after Zhao’s dismissal, on June 30, the mayor of Beijing read out his report on the protests. Zhao had sought to overthrow the socialist order in China and replace it with a liberal capitalist system, the mayor declared. He offered damning evidence of how Zhao developed his supposed plot: “Especially worth noting is that last year on September 19, Comrade Zhao Ziyang met with one American ‘extreme liberal economist.’ ”

Which “extreme liberal” had Zhao met on September 19, 1988? The answer opens the door to a strange, incongruous tale, because the American economist who had allegedly plotted with the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party was none other than Milton Friedman.

Friedman first traveled to China in 1980. When he celebrated his 68th birthday that year, he was perhaps the most famous economist in the world. He had appeared on the cover of Time in 1969, in an issue that focused on the “new values” that would define the 1970s. With his diminutive stature, forceful personality, and Cold War faith in the free market’s inevitable triumph over communism, he was an instantly recognizable public personality, equally at home walking the plush carpets of the White House and expounding to the public from television studios.

Academically, Friedman had established himself as an expert on inflation and consumer behavior. Believing that people behave rationally in their own self-interest, he predicted in 1967 that a sustained period of inflation would not drive down unemployment, directly contrary to the mainstream view at the time. That was before oil crises and the Nixon administration’s economic policies shocked the American economy. During 1973, the U.S. inflation rate more than doubled, reaching 8.7 percent in December. (It would climb to 14 percent by 1980.) Through this period of soaring inflation, unemployment remained stubbornly high—a phenomenon known as stagflation, which was exactly what Friedman had warned of. If one test of an economist is the ability to predict economic phenomena and their consequences, Friedman had triumphed. He won the Nobel Prize in 1976.

But in American public life, Friedman was a firebrand and a polemicist—an extreme advocate for a particular brand of free-market fundamentalism. Economist Paul Krugman wrote of him, “His showman’s flair combined with his ability to marshal evidence made him the best spokesman for the virtues of the free markets since Adam Smith.” In 1980, Friedman and his wife, Rose, released a popular overview of their ideas entitled Free to Choose. This full-throated defense of free-market principles also became a 10-part television series. It made Friedman’s name synonymous with a total faith in the free market. When he served as a senior economic policy adviser for Ronald Reagan’s 1980 presidential campaign, his influence grew even greater.

In a television interview with Phil Donahue that aired in April 1980, wearing a tan suit under the bright studio lights, Friedman had contrasted his ideal society with socialist countries like China. Donahue asked intently, “Did you ever have a moment of doubt about capitalism and whether greed is a good idea to run on?”

Friedman cocked his head to the side and grinned. “Tell me, is there some society you know that doesn’t run on greed? You think Russia doesn’t run on greed? You think China doesn’t run on greed? … If you want to know where the masses are worst off, it’s exactly in the kind of societies that divert from [free-market principles].”

So Friedman was astonished when, in late 1979, he received an official invitation to visit China. The United States and China had announced that they would normalize relations on December 15, 1978, the culmination of a process of rapprochement symbolized by President Richard M. Nixon’s and Chairman Mao Zedong’s handshake in 1972. Academic exchanges had just resumed, and Friedman would be part of the first set of scholars invited to give lectures in China through a new official program. Friedman quickly accepted, but he confessed in a letter to a friend that the invitation was “a phenomenon that I find almost literally incredible.” The world’s leading advocate of free-market fundamentalism was to be one of the first American academic visitors to the People’s Republic of China after it had endured decades under a state-controlled economy.

Milton and Rose Friedman arrived in China on September 22, 1980. The trip was a struggle from the start. Milton complained about the “terrible body odor” of a man “dressed as a worker” in the passenger seat of his chauffeured car, as he wrote in his memoir, Two Lucky People. Regrettably, this odiferous individual turned out to be a deputy director of the Academy of Social Sciences, which was hosting Friedman’s lectures.

China in 1980 had barely escaped from the poverty that Mao left behind when he died in 1976. Deng Xiaoping, who emerged as China’s leader, had declared a momentous new era of Reform and Opening in 1978, but China’s gross domestic product per capita that year was only $175—and it showed. “The general impression on walking or driving down the streets is one of drabness and dullness and dirt,” Friedman noted. “Almost the only place there is light and beauty and cleanliness and variety is on the stage.”

Why had this poor socialist country invited Friedman, of all people, to provide economic advice? One word: inflation. Under Mao, prices were fixed by state fiat, repressing any inflationary pressures for decades. In 1952, 15 yuan could buy “10 kilogrammes of rice, 5 kilogrammes of flour, 1 kilogramme of pork, half a kilogramme of sugar, half a kilogramme of table salt, 15 kilogrammes of vegetables, 1 metre of white cloth, 2 cakes of soap, 25 kilogrammes of coal, half a kilogramme of edible oil, half a kilogramme of kerosene and some other consumer goods such as aluminum ware, stationery and medicines,” according to the Peking Review, which boasted 23 years later, in 1975, that the same sum of money (roughly $8.37 at official rates that year) still bought the same quantity of goods. Propagandists regularly announced that communism had successfully eradicated inflation in China, and painted inflation as a scourge of capitalist (or “liberal”) societies.

As China’s rulers under Deng Xiaoping began to loosen controls and free up prices, they knew that inflation might appear. With his academic achievements in predicting the “Great Inflation” of the 1970s, Friedman seemed a natural fit to help teach the Chinese leaders how to avoid this alarming prospect.

But their perception of Friedman was incomplete, to say the least. At one internal meeting of banking officials, a young bureaucrat explained the “two factions” in American economics in broad strokes: “Keynesians advocate inflation, and Friedman is opposed to inflation.” They seemed completely unaware of his missionary commitment to the free market.

By the time Friedman visited in 1980, Chinese economists still had only limited experience dealing with foreigners. In the late 1970s, curious Chinese economists began to read about ideas from the outside world—including the capitalist West, which had once been a bête noir. Zhao Ziyang believed his country should use foreign ideas to figure out how to reform its failed socialist economy. China’s reformers sent out invitations to all corners of the globe—to the socialist countries of Eastern Europe, the capitalist countries of Western Europe, and even to the United States. The invitation to Friedman was part of a much larger effort to learn from abroad and draw on ideas from around the world to shape China’s transformation.

After seemingly endless logistical snags, the Friedmans settled into their hotel. Milton delivered four lectures on topics such as “the mystery of money” and “the Western world in the 1980s.” His audiences of officials and scholars listened as he dismissed the idea that inflation appeared only in capitalist societies. Inflation was neither innately “capitalist” nor “communist,” he said. Instead, government itself was the root cause of inflation, which could be cured only by “free private markets.”

To the Chinese economists in the audience, these ideas were radical; to many of the country’s less liberal leaders, they were menacingly extreme. Friedman was preaching the free market rather than teaching them how to build policies to fight inflation. In a society that had not yet formally accepted any role for the market—let alone free private markets—this approach was anathema.

Accustomed to being feted as a visionary, Friedman did not receive the embrace he anticipated for his lectures. At a discussion after lunch one afternoon, his frustration boiled over. A Chinese researcher mentioned “the internal contradictions of capitalism,” a standard Marxist phrase. Friedman was done playing nice. He counterattacked, asserting that there were no such contradictions. He launched a fusillade of sharp observations about Marx’s incorrect predictions about the future of capitalist development. Ordinary people would always live better in capitalist countries than in socialist countries, he proclaimed.

The Chinese were quite prepared to listen to a Western economist discuss “the mystery of money” but had not expected to face such a diatribe. The next day, his hosts sat him down in a hotel room and delivered a long lecture on the triumphs of the Chinese Communist Party. It was an education—and a firm warning. The Friedmans departed China a few days later, on October 12, with Milton angrily exclaiming that the Chinese officials they had met were “unbelievably ignorant about how a market or capitalist system works.”

The Chinese, meanwhile, had learned the hard way about Friedman’s dual persona, which made it impossible to separate his expertise on inflation from his fiery condemnations of socialism. The economists he met, despite their eagerness to engage with a world-renowned expert, complained that he had been stubborn, impolite, and exasperating.

It was a rocky start for renewed U.S.-China exchanges. Shortly after Friedman departed China, a prominent conservative elder delivered a speech that criticized liberalizing foreign influences as a grave danger to Chinese socialism. “Foreign capitalists are still capitalists,” he warned. “Some of our cadres are still very naïve about this.”

In the years after 1980, China boomed under the policies of Reform and Opening. Zhao Ziyang steered the economy as the country’s premier. Deng directed him to figure out how to bring the market reforms that had quickly taken hold in agriculture into the cities and state-owned enterprises, which made up the bulk of the economy—and to do so without destabilizing society as a whole.

Problems proliferated wherever Zhao looked. State enterprises were massively inefficient, often running up huge debts without any consequences—but they employed millions of people, so any reforms leading to layoffs would devastate people’s livelihoods. Everyday goods from clothing to toilet paper were often in short supply because their prices were kept artificially low—but if the prices of these goods rose faster than incomes, people would be unable to afford them. The growth of industry had been slow because, without the ability to make a profit, enterprises had no incentive to improve—but if industry was allowed to grow without any constraints, the economy would overheat and inflation would soar. Most of all, at every step conservatives decried any use of the market as conflicting with China’s socialist system.

Zhao and his network of economists devised an ingenious solution. Enterprises would still have to meet planned quotas, and everything they produced to meet the quotas would still be sold at a state-set price. But beyond those quotas, enterprises could produce whatever quantity of goods they wanted and sell them at whatever price consumers would pay. It was a “dual-track” system: the old system remained in place, but it very quickly became only a small part of a much larger and more vibrant economy. Think of the old planned economy as a shriveled bonsai: Zhao didn’t suddenly stop watering it, he just planted a forest around it.

This policy worked, and growth skyrocketed in the years from 1984 to 1988. But it was a temporary solution; the unresolved problem of prices remained a thorn in the side of China’s rulers. Zhao was promoted to general secretary, and he and his economists canvassed the world for ideas, listening to Nobel Prize–winning Keynesians, cosmopolitan World Bank officials, and battle-scarred veterans of Eastern Europe’s economic struggles. They began to carefully craft a new agenda for price reform. But in the summer of 1988, Deng Xiaoping, the paramount leader, finally lost his patience. He decided to order an overnight liberalization of the price system. His advisers warned vainly that growth was so overheated that freeing up prices would lead to dangerous and unpredictable price increases. But Deng had made up his mind. In mid-August, prices around the country were freed.

A crisis immediately followed. Across the country, the fear of inflation turned ordinary streets into cinematic tableaux. In the southern city of Wuhan, crowds of frantic consumers besieged the Qingshan Friendship Store, which sold gold. They crashed against the store’s tightly sealed metal gate, their wrists thrust between the bars and their hands waving thick wads of cash, urgently withdrawn from bank deposits to be converted into precious metal. The frantic saleswoman inside grabbed their cash as quickly as she could, doling out as much 24-karat gold as the shop possessed. As money lost value, scenes like the gold frenzy in Wuhan seized the country, and a survey of 32 cities revealed that prices had risen nearly 25 percent in the month of August. An atmosphere of crisis descended on party leaders. By the end of the month, conservatives opposed to market liberalization had scrapped the reforms and were preparing a major period of retrenchment to stabilize the economy.

At this moment of crisis, Zhao made a characteristically bold decision. He would meet with a leading foreign economist to seek advice about how to get inflation under control—and not just any economist, but the notoriously outspoken Milton Friedman, once again called upon for his expertise on inflation. Subsequent events would show that Friedman was a risky choice indeed.

When the Friedmans planned their September 1988 trip, Milton did not yet know that he would be invited to meet with Zhao. The occasion for the trip was a conference on economic reform in Shanghai, the bustling coastal metropolis that had become a symbol of China’s transformation. In the years since his 1980 visit, Friedman had maintained correspondences with a variety of Chinese people, and he was eager to return.

The most colorful of his correspondents was a loquacious finance student at Xiamen University who had started translating a book of Friedman’s essays—and even sent him a photograph of herself sitting on her pink upholstered bed. Friedman dutifully responded, sending additional copies of his books and encouraging her to find him more Chinese disciples. It was this desire for greater influence in the world’s most populous country that impelled the 76-year-old economist back to China.

Soon after arriving, Friedman joined Shanghai Party Secretary Jiang Zemin (who would later become China’s president) for lunch. At the meal, Friedman argued for the importance of privatization and free markets. Jiang responded by stressing that these ideas would be politically very difficult. Even so, Friedman praised Shanghai’s development. “The few free markets,” he wrote, “had grown into extensive free markets, selling a wide range of products, involved not only in retail but also in wholesale trade. … Color and variety had graduated from the theater to the streets.”

Despite the summer’s economic chaos, the moment seemed right to Friedman to press his case for a rapid liberalization of the economy. At the Shanghai conference, he sat behind a table in the front of the room, his head just barely peeking over the microphone and jug of water provided for him. Next to him sat a Communist Party economist named Pu Shan, who wore a tightly buttoned Mao jacket and a crewcut like a silver helmet.

Friedman gave his usual impassioned case for free private markets. In his response, Pu Shan upbraided the distinguished visitor and asserted that China’s economic system might, in fact, prove superior to an economic system based on free private markets. Friedman dismissed the critique as the political correctness of an uncreative apparatchik—but it was clear that Friedman’s evangelizing message had once again failed to find as warm a reception as he had hoped.

One loyal acolyte did make an appearance, however. The correspondent from Xiamen University arrived unannounced at the door to his hotel room. She had taken the train from Xiamen, a seaside city on the Taiwan Strait. As Rose Friedman padded around the room barefoot, the distraught student pleaded with Friedman to get her a ticket to his sold-out lecture at Shanghai’s Fudan University. He obliged. The next day, she sat beaming in the front row at his lecture to a crowd of 400 students. Even if many Chinese officials viewed him as too radical, Friedman could clearly still inspire devotion.

After the visit to Shanghai, the Friedmans set out on a trip through southern China—but this leisurely tour soon came to an end. He received a summons to go north to the capital, and there was no time to waste.

In Beijing, Friedman stayed amid the tranquil ponds and elegant villas of the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse, the residence of visiting dignitaries. With inflation burning through the Chinese economy, Zhao and his network of economists were in desperate need of new proposals. Friedman had proved unpredictable, but his hosts seemed to believe that his expertise might offer necessary insight into the greatest test that China’s new economy had yet faced.

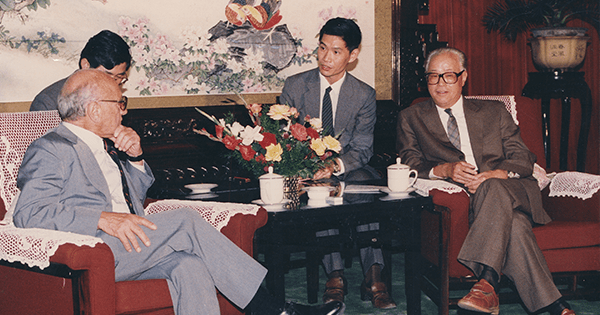

At 4:30 P.M. on September 19, Zhao greeted Friedman in the Great Hall of the People. Wearing a well-tailored brown suit, a white dress shirt, and a plaid tie, a smiling Zhao shook Friedman’s hand. They sat down in plush red chairs and began to talk.

Zhao laid out the challenges facing China’s economy. “What we intend to do in carrying the reform further is to reduce the number of prices that are under the dual-track system and state control,” he said, according to a transcript of the meeting. “However, just as we are ready to go a step further toward price reform, we are faced with difficult problems, especially sizable inflation.” Zhao asked for Friedman’s assessment of the effects of inflation. “Can the people take such a shock, both economically and psychologically?” Then Zhao raised an even more fundamental question: “Why did inflation occur in China?”

Friedman responded critically. He pointed to the dual-track system as one cause of inflation because it produced so many inefficiencies in the economy, from queuing to shortages, and pumped up prices in the sectors that were open to the market forces of supply and demand. Friedman was similarly dismissive of other “halfway” measures that delayed what he saw as the only real solution: full privatization and marketization.

However unconvinced Friedman may have been by Zhao’s arguments, he was clearly impressed with the Chinese leader’s command of economics. He remarked, “On hearing your analysis of China’s economic situation, I believe you are a professor by nature.”

“I only went to high school,” Zhao replied, laughing.

The conversation continued, touching on proposed reforms to exchange rates, state-owned enterprise management, and the central government’s authority over the economy. Zhao begged Friedman to understand China’s special circumstances: without a developed banking system, China could not tighten the money supply to control inflation, as the U.S. Federal Reserve does. Friedman continued to push for immediate, sweeping market reforms. After nearly two hours of heated exchanges, Zhao ended the conversation. The pair had reached no consensus on the best path for China.

Zhao usually remained seated as his guests departed, but on that September day he had something else up his sleeve. He stood, walked Friedman all the way out to his car, and even opened the car door for the American economist. It was an extraordinary gesture. Despite the inconclusive tone of the meeting, this gesture provided ample fodder for Beijing’s gossipy network of policymakers and scholars, who were used to parsing senior leaders’ views from such minutiae. Rumors began spreading about the close connection forged between the two men.

In the Chinese press, Friedman’s trip was reported in laudatory terms. The official People’s Daily wrote buoyantly about the meeting, transforming Friedman’s radically pro-market ideas into more generic views that cohered with Zhao’s goals for reforming the economy. The visit was presented in the state-run media more as a public relations boost for the beleaguered Zhao than as a meaningful intellectual exchange.

Before leaving Beijing, Friedman attended a lavish banquet with some of his hosts. Tanned and clad in a red plaid shirt and white linen jacket, the American economist grinned broadly and clinked brimming shot glasses with his Chinese counterparts. Indeed, Friedman praised his meeting with Premier Zhao and the Chinese leader’s economic savvy—a striking contrast to the “unbelievably ignorant” officials he had disparaged after his 1980 trip.

What of the alleged plot to overthrow socialism in China that would come back to haunt Zhao? Friedman undoubtedly wanted to see capitalism replace socialism in China, but he certainly did not conspire to bring that about in the collegial conversation with Zhao. The irony is that the press accounts about their camaraderie, which shored up Zhao’s credibility in late 1988, laid the groundwork for Zhao’s denunciation the following June.

In articles and interviews, Friedman also worked to publicize his grand reception in China. He had been fiercely attacked in the 1970s for his “responsibility” (as The New York Times put it) for supporting the repressive junta in Chile. So in announcing his return from China in the Stanford Daily that October, the always provocative Friedman wrote with biting irony, “Under the circumstances, should I prepare myself for an avalanche of protests for having been willing to give advice to so evil a government?”

No such protests came, and Friedman remained optimistic about China’s future. In a December 1988 interview with Forbes, he predicted that major pro-market changes were imminent.

Yet almost immediately thereafter, the reform agenda in China collapsed. Soaring inflation made daily life more expensive and hurt job prospects for young people graduating from college. Many Chinese voiced a sense of betrayal that the benefits of the reforms were distributed unequally, with the powerful getting richer and the powerless getting poorer. And they were angry about pervasive corruption and the lack of political reform.

Students nationwide launched protests centered on Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in the spring of 1989. Some of them called for reform and others called for revolution. As weeks passed and the crowds in Tiananmen Square grew larger, the world watched the protesters with fascination, enthralled by their conviction, bravery, and youth.

In the secret halls of the leadership compound, the top party chiefs fought fiercely over whether to impose martial law and quell the protests by force. The sight of popular movements toppling communist regimes in Eastern Europe terrified China’s rulers. Zhao vociferously opposed turning the military on the people, but his views lost out after a string of combative meetings in May. Following the last of those heated sessions, Zhao walked out to the square to speak to the students directly. He held a small megaphone close to his mouth as his voice filled with emotion. “We came too late,” he told the students. “Whatever you say and criticize about us is deserved.”

The next day, martial law went into effect across the land. The bloody crackdown began in the night of June 3. By the morning of June 4, Tiananmen Square had been emptied of the students who had camped there for weeks. They left behind only a few bloodstains on the stones, newly scarred with the tread marks of tanks. Mao’s official portrait still hung from the Gate of Heavenly Peace. In the imperial city that spread out below his empty gaze, an unknown number of protesters had been killed and wounded.

Later that month, with order restored across the country, party leaders formally dealt with Zhao. He was denounced for supporting the protests, “splitting the party,” and undermining socialism. The engagement with foreign economists pursued by Zhao and his network of economists came under direct assault, evidence of his alleged mission to push China to abandon socialism. And there was the Beijing mayor’s report citing Milton Friedman. Zhao had no way to escape this guilt by association or the other charges against him. His name was eliminated from official histories and has rarely appeared in print in China.

Friedman, too, became persona non grata after the crackdown. But as a symbol of the liberal path that had been forcibly prevented, he was inundated with pleas for help from young economists seeking to flee the country. The optimism about China’s future that Friedman had voiced only a few months earlier vanished with Zhao. For Friedman, who had long argued that economic freedom and political freedom were inextricably connected, the Tiananmen tragedy demonstrated the danger of conducting economic reforms without liberalizing the political system.

“No totalitarian state has yet managed to make the transition to a reasonably free society,” Friedman wrote in late June 1989. “China had the opportunity to be the first to do so. I very much fear that it has squandered that opportunity. … What a tragedy.”

With Zhao out and conservatives empowered, the fallout over the crackdown at Tiananmen soon broadened into a rolling back of the economic reform policies. Conservatives consistently blamed foreign infiltration and interference for China’s domestic troubles, ranging from the student “rebellion” to the lingering economic woes. Friedman fit into this narrative, but it extended far beyond him. As an anticommunist contagion continued to spread throughout Eastern Europe, pulling down once-invincible regimes, the Chinese Communist Party held onto power, white-knuckled, and its official line became more firmly anti-Western than it had been since the Mao era.

But Deng Xiaoping refused to abandon all the progress that China had made since the late 1970s. On January 17, 1992, he traveled to southern China for what was supposedly a family vacation. Putting all his accumulated credibility on the line, the 88-year-old Deng surprised the world by giving a series of informal speeches urging the resumption of intensive reforms. The gambit worked: by mid-February, after two and a half years of deep freeze, reformers burst back onto the scene with sizzling vigor.

“I don’t think the [conservatives] will be able to obstruct reforms, especially in coming months,” one prominent reformer, Wu Jinglian, said at the time. “In coming years, if we do not make mistakes, I think the changes will go forward.”

He was right. Although Zhao remained under house arrest, many of his policies resumed—without acknowledgment of their supposedly treacherous origins. Among the restored policies was the study of economic ideas from around the world.

Fueled by the need to catch up for lost time, the pace of reform quickened. In 1993, China’s gross domestic product increased by nearly 14 percent as industrial growth spurted. Ambitious domestic entrepreneurs pursued a new world of opportunity, and government officials implemented sweeping changes to increase the efficiency of state-run enterprises. As China opened to the outside world again, foreign investment flowed into the country. China would experience extraordinary growth in the decade ahead, becoming one of the world’s largest economies.

Even the “extreme liberal” Friedman was welcomed back to China. Traveling to Shanghai and Beijing in October 1993 for official meetings, he was astonished at the rapid pace of development. At the end of his trip, he returned to the Great Hall of the People, the site of his fateful encounter with Zhao, to meet with China’s new president, Jiang Zemin. Although they had met in Shanghai in 1988, no fond feeling existed between the men. Friedman repeated his arguments about the necessity of absolutely free private markets. But Jiang delivered what Friedman perceived as a canned speech about the successes and challenges of the Chinese economy, and the meeting ended quickly. It was a far cry from the two probing hours he had spent debating Zhao. Friedman wrote after the meeting, “I conjecture that Jiang did not really want to hear what we had to say.”

The public response was similarly muted. A short item in the People’s Daily described how China’s new leader had “introduced” China’s reforms to Friedman and invited him to conduct research on the economy. The memory of Friedman’s tumultuous role in the 1980s had been erased from history. He was simply another foreign expert invited to a country that was once again open for business.

In more recent years, the senior echelons of the Chinese Communist Party have occasionally returned, like Zhao 30 years ago, to an interest in Friedman’s inflation-fighting wisdom. Senior officials at the People’s Bank of China, the central bank, have even quoted from Friedman’s Free to Choose to describe their anti-inflationary goals. Once characterized as an agent of unforgivable treachery, Friedman has now become a foreign name to be cited in formulating official policies.

Even so, the forces that targeted Zhao and Friedman in the summer of 1989 are still alive in China today, opposing liberal ideas and market reforms. One of the most prominent antagonists to these conservative forces is the liberal economist Mao Yushi, now in his late 80s. The founder of an organization called the Unirule Institute of Economics, dedicated to free markets and reform, Mao has adopted Friedman’s contrarian persona, writing brash, quotable essays promoting liberal principles. He is regularly attacked as a “traitor” and a “slave of the West,” but he continues undaunted. In 2012, the Cato Institute awarded him the Milton Friedman Prize for his advocacy of individual rights and free markets.

Opposition to liberal ideas has enjoyed a resurgence under president and party chief Xi Jinping, and it may no longer be possible—if it ever truly was—for both inflation-fighting bureaucrats and outspoken free-marketeers to lay claim to Friedman’s legacy. I asked Mao Yushi why he thought Friedman remained an important figure in China today.

“Since the new government came to power, China’s reforms have moved backward,” he told me. “China is a state that opposes liberalism. The government places many unnecessary restrictions on the people’s freedoms … so it is extremely important to promote liberal ideas in China. And this is the reason why [Friedman] is in demand.”

How can we understand the mixture of wariness and interest that occasioned Milton Friedman’s invitations to China? China’s rulers clearly believed that economics—and economists—could be dangerous. But their consistent interest in this particular interlocutor, as unpredictable and pugnacious as he was, reveals their extraordinary fascination with this dangerous knowledge. They needed the best ideas from around the world to allow the Chinese economy to boom, and sometimes that required dealing with thinkers whose expertise was invaluable but whose views were unpalatable. No outsider personifies this complex duality better than Milton Friedman.

The exploratory, open-minded spirit that brought Friedman to China has weakened considerably there today. Contacts with foreign economists certainly continue, but they occur against a background of suspicion. In August 2013, shortly after Xi Jinping came to power and began establishing his centralized, strongman style of rule, cadres from across China massed in Beijing to hear him speak. Facing the assembled officials at this National Propaganda and Ideology Work Conference, Xi painted an ominous landscape in dark brushstrokes. “Western anti-China forces” are seeking “to overthrow the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party and China’s Socialist system,” he reportedly told his subordinates. He seemingly presented a choice between infiltration and total refusal, with only one option truly open to loyal Chinese communists.

“If we allow [hostile foreign forces] to have their way,” he intoned, “those false efforts will lead people astray, which is bound to bring chaos to the Party’s hearts and the people’s hearts, endanger the Party’s leadership and the security of the Socialist national regime.” In the face of these threats, Xi said, the party must “dare to bare the sword.”