Mr. Olympia

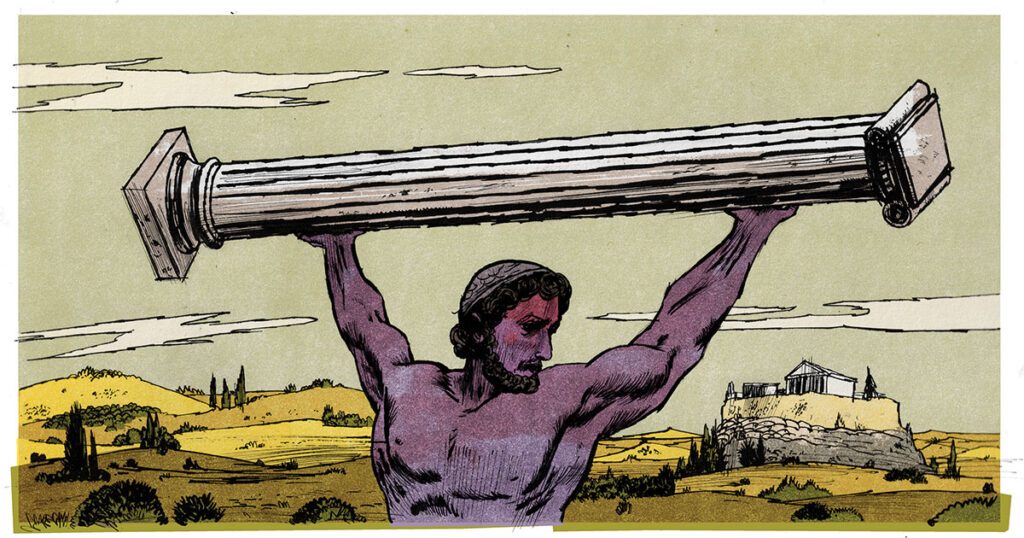

When the ancient Greeks looked at human muscle, they saw something different than we do

The earliest evidence of weightlifting in the ancient Greek world is a sandstone block from Olympia, weighing about 315 pounds, with a pair of deep, smooth grooves worn into the long top side of the stone. The grooves make it possible to picture the event described by the words cut into the rock: “Bybon, son of Phorys, lifted me over his head with one hand.” A similar inscription can be found on a bigger, heavier rock, hundreds of miles away on the island of Santorini. Seven feet long, six feet in circumference, the black volcanic boulder weighs more than 920 pounds and bears this chiseled announcement: “Eumastas, the son of Critobulus, lifted me from the ground.”

Many classicists have been skeptical of the boasts carved on these stones. Few of them have known much about lifting weights. The article “Weightlifting in Antiquity,” the most detailed study of the topic, was published in 1977 by Nigel Crowther, the only classicist of that era who had been a competitive powerlifter. Crowther, now emeritus professor of classical studies at Western University in London, Ontario, contended that both ancient claims are plausible. The stone of Bybon at Olympia, he wrote, is no heavier than barbells hoisted by the 19th-century Prussian strongman Arthur Saxon. The rock of Eumastas on Santorini, he added, could possibly have been raised with a movement resembling the deadlift—at the time of Crowther’s writing, the deadlift world record was a little more than 885 pounds, close to the 920 Eumastas supposedly hoisted. (The record has risen since then. In 2020, in Iceland, Hafþór Júlíus Björnsson deadlifted 1,104.5 pounds.)

In the whole of Greece, archaeologists have unearthed only two other stones that show signs of having been used in some way akin to modern weightlifting. Both were found at Olympia, with one of the limestone chunks inscribed, “I am the throwing-stone of Xenareus.” Meanwhile, very little surviving art from ancient Greece portrays anything like heavy weight training or weightlifting. One painted fragment of a wine cup—possibly from the sixth century BC—shows a slender boy struggling to lift a stone. And yet, ancient Greek art—from seal stones to statuary—depicts a plethora of bulging muscles. So why is there so little written or visual evidence of ancient Greek weightlifting?

I put that question to Charles Stocking, who holds a joint appointment in classics and kinesiology at the University of Texas at Austin—and who, like Nigel Crowther, was once a competitive powerlifter. Stocking says that “our perspective is historically conditioned. And what I mean by that is, lifting weights is so much an essential part of modern sport and fitness that the two are almost synonymous. But this is a tradition that developed. And it developed tangential to sport.”

Because ancient Greek athletics developed in the context of religious ritual, “supplemental exercises wouldn’t necessarily take center stage the way they do today,” Stocking says. Moreover, human strength was measured with a different frame of reference back then. Today, Stocking says, we associate strength with “the ability to lift heavy things,” but for the Greeks, who loved wrestling, strength was determined by “your ability to move another body. And how do you develop that strength? Well, a lot of it would be from just moving other bodies. As opposed to picking up rocks.”

The Greek word μυς (transliterated as mys), the term that distinguished muscles from general fleshiness, appears in two battle skirmish scenes in The Iliad, but the word’s usage there conveys no sense of muscle’s purpose. In the first instance, a warrior suffers a wound

at the top of the leg, where a man’s

muscle is thickest: around the point of his spear

the tendons were sliced apart, darkness shrouded his eyes.

A few moments later, another warrior is struck on the shoulder:

the spear point stripped away

the base of his arm from its muscles, shattered the bone.

He fell with a thud, and darkness shrouded his eyes.

These lines (in Peter Green’s translation), which describe minor events in a major battle, appear to be the oldest surviving literary mentions of individual muscles as distinct anatomical features. Still, these examples are outliers: in writings from ancient Greece, there is near-total silence when it comes to muscles. Homer often alludes to warriors’ physiques (rows of broad shoulders in lines of battle) and often cites big bodies as indicating strength, but in The Iliad, he never explicitly names muscles as an aspect of physical prowess.

Muscles apparently were not a sign of the power to do violence or of any other kind of power. In The Origins of European Thought, the classicist R. B. Onians states that in Homer’s time, it was “the knee [that] was thought in some way to be the seat of paternity, life, and generative power, unthinkable though that may seem to us.” In The Iliad, we see warriors dealing death blows by unstringing the knees of their enemies. From about 600 BC, statues of naked young men were a common sight in sanctuaries, cemeteries, and public spaces all over Greece; these statues, called kouroi by art historians, also focused viewers’ attention on the knee joints. Muscles, by contrast, were not an aspect of a person’s appearance. And muscles were not identified as playing any part in the process of bodily movement. Muscles were known as a distinct substance, located in the vicinity of tendon and bone, but no particular function or significance seems to have been ascribed to them.

Plato never used the word mys, nor did Aristotle or any of the Greek playwrights. Even the authors of Greek medical texts barely mentioned individual muscles, as the historian Robin Osborne has pointed out while noting that ancient physicians showed a general “lack of interest in what muscles do.” Only two surviving medical texts prior to the first century AD mention muscles by name, as mys, according to the classicist Tyson Sukava. Neither of those medical texts connects muscles with movement.

So how can there be so many bulging muscles in ancient Greek art but so little awareness of muscular function? The odd answer is that the ancient Greeks saw biceps, pecs, quads, and glutes in very different ways than we have learned to see them. We see what we are taught to see—even when looking at our own flesh—until we are forced, by slow processes of discovery, to agree on seeing ourselves anew.