As of this writing, we have 108 comments—a new record!— on our last column, “Above the River of Your Longing.” Some, of course, are direct responses to that column’s prompt (use your name as a starting point for your poem); others were exchanges among participants, and I must praise the level of discourse. Respondents are unfailingly courteous and generous, fostering a sort of celestial poetry workshop in which the spirit of collaboration prevails. And this week, there was a lot of well-merited applause for our poetic efforts.

Writers were encouraged to incorporate anagrams or to consider namesakes in their poems. Emily (no last name given) combined these in a terrific prose poem with a fetching title, “An Anagram of Sister is Resist”:

Our Hebrew names illumined the power differential—she was Batya, Egyptian princess, rescuer of Moses, daughter of God; I was merely Ahuva, one who is loved. Her married name contains Batya, as well as aleph and bet, print and type, poet and poets. Poor Ahuva, Batya taunts, pink-skin Batya, twinkle-blue-eyes Batya. Psst. Schlep on back to your own name. We were not twins of a gazelle, as it happens. We were homophones, at best, waist and waste, wine and whine; or we were lines of different slopes, uneven stoops, destined to cross one another. I could not opt out, swipe left (her dominant hand). Pots and pans—she washed, I wiped. It was always hook-and-loop, over-under, stabbing at parity. I’m stabbing it now, stealing these words right out from under her. We both got cancer, the same organ, the same summer, though I was fourteen months younger. Cancer’s not contained in either of our names, Hebrew or English, married or maiden. Breast is only in her name. Both is only in her name, but I lost both; Batya, just the one.

Pamela Joyce Shapiro said, and many of us agreed, that Emily’s poem “transcends the prompt.” Pamela singled out this sentence for praise: “We were homophones, at best, waist and waste, wine and whine; or we were lines of different slopes, uneven stoops, destined to cross one another.”

Christine Rhein’s wit and ingenuity were on display in her poem, which grants her name an active existence independent of the poet’s:

Christine Rhein

doesn’t rhyme, despite her inner

sinner, her hidden Einstein

shine, that jumble of tries, retries,

cries making her no Christina

Rossetti, no musical Queen

Christine, no gold-laden Rhine-

maiden, though of course a poet

knows to hold her secret siren hints

close to her chest, to pen her nicest

nest of nets, keep her work ethic

echt, but still, Christine Rhein never

rhymes, except, on a night like this,

with mis-schemed lines and—gulp,

gulp, gulp—pristine wine.

The infinitive sequence that concludes “keep her work ethic / echt” competes with “her hidden Einstein / shine” for my approbation.

Jordan Davis went to town with anagrams, treating them as if they were properties of the self:

My anagrams—so many javas, divas,

and some divans, an avid Dido, odd—

So vain to say I feel unseen by them,

but here we are, alive, a dad van man.

And with my government? sad donor

of android moths, jihad doorman, avast!

a matador and handmaid in a jar.

A dastard atavism manhood nods…

That’s somewhat more like me. Let’s add poet:

Jade’s orthodontias vamp adaptive smooths,

starvation’s jaded oomph (o pedant jive)

pajamas shoved dirt onto, driven hot…

Good grief. If nomen omen is a thing

My self and name require more change to sing.

Constraints are paradoxically liberating, because they compel the imagination to combine words rather as a chemist may mix the fluids in test tubes. Thus, we get explosive surprises like “pristine wine” (to rhyme with her name) in Christine Rhein’s poem and, in Jordan Davis’s, striking strings of words I’ve never before seen conjoined, like “starvation’s jaded oomph (o pedant jive).”

Diana Ferraro’s cleverly titled “Nada” is a tour de force of anagrammatic perfection, a sonnet with a trace of Shelley (“I err if I fear!”) and a pinch of Hamlet (“Ferraro and Di are dead”).

Dear friend or rife foe,

Ferraro and Di are dead.

Deaf in an era of fire,

I find a door.I err if I fear!

One fir oar

and free rein

fare near and afar.An Indian rain,

a reef,

one fair ford:

dire roe for dinner.No art, no air, no road.

No friar aid.

Millicent Caliban’s “A Missing Friend” may quicken speculation about the bearer of that formidable persona:

Millicent is not my name assigned at birth.

Like Norma Jeane, I chose one for the screen.I am a liar.

In air, my lair. A yarn, in rain.

My mail may aim ram rail.

Lima? Iran? Mali?

A man in an army? IRA?

I am an ami MIA.

Wonderful the palindrome that concludes this unusual ode to made-up names. Norma Jeane was Marilyn Monroe’s given name, and whether the author is giving us a clue to her own identity or not, the generative power of that name yields paradox, alliteration, query, and a remarkable self-description: an amiable friend who, in some figurative sense, is missing in action, perhaps disguised as an Irish revolutionist.

In “That’s Not All,” Sally Ashton sallies forth with a ton of energy, and no ash:

Thy sly ally,

too shy to sally,

shall be long

and tall, a tally

not diminished

to Sal of yon canal

but more mustang,

y’all. Not astronaut.

In a field of her

own so shall not

atone nor hash

more words. Also

known as Slash.

From Michael C. Rush, we get the homophonic “My Kill” with an arresting opening line and a marvelous observation of “Muse Circe”:

User, shame his accuser, Icarus!

Search, share his emails, his crucial miscue.

Came the liar’s share, harm, malice:

cash accrues in the camel’s arse.Cherish slim circus charms:

miracles are crimes of misrule.

Muse Circe reclaims her lucre—riches!—

as realism hums in musical realms.Rush a clumsier amicus clause:

the lame cures aim cliché lures

as reams scale cruel serial relics,

raise eclair’s cream-cache chimeras.Ears hear much, harsh airs’ sham curse.

A miser cries. His heirs care.

If I had more space, I’d quote the full breadth of several other entries—but unlike the imagination, space here is finite, so instead I’ll praise some more of my favorite lines. From Christa Overbeck, “the A to Christ;” from Kaleiheana Stormcrow, “Crows call in the east, hail a storm;” and from Paul Michelsen, “LISA BONET ATE NO BASIL.”

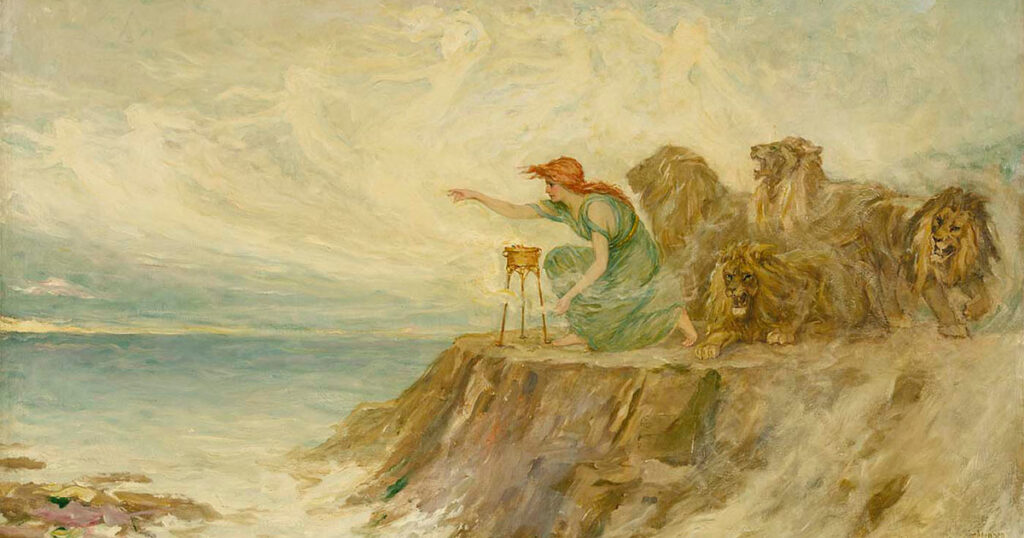

For our next round, write a poem using as your point of departure one of the following five “Proverbs of Hell” by William Blake. Your poem may, by anecdotal means, illustrate or confute the infernal axiom you have chosen. It need not quote the Blake line you chose; you can let your readers guess. Limit 15 lines. Or write a cogent one-paragraph discussion, elucidation, and analysis that brilliantly addresses (or argues with) the line. Deadline: Tuesday, March 4.

- Drive your cart and your plough over the bones of the dead.

- Prudence is a rich, ugly old maid courted by Incapacity.

- The nakedness of woman is the work of God.

- The tigers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction.

- Sooner murder an infant in its cradle than nurse unacted desires.