George Balanchine left Russia in 1922, when he was 18. He didn’t go back for 40 years, until October 1962, when he returned for an eight-week tour with his dance company, the New York City Ballet. He lasted about a month before absenting himself from the tour for week-long breather at home in New York, to recuperate from the stress of the tour, which was almost too much for him. Part of the stress came from the standoff in late October between the United States and Russia during the Cuban missile crisis. Everyone was nervous and worried, even before President Kennedy announced that the United States was prepared to retaliate on Soviet soil for a nuclear strike. Talk among the dance company was of where to hide and how to get out if worse came to worst. Balanchine bore up under that stress remarkably well, even when an American aircraft was shot down over Cuba on October 27. In the afternoon, Soviet troops and a crowd of protesters surrounded the American embassy. The embassy warned Balanchine to stay away from the theater that night for fear of a hostile audience. But the company went, despite the danger. Balanchine had been training himself since his escape at 18 to live in the present moment, and so his dancers danced, holding nothing in reserve. Instead of a hostile audience, they had an enthusiastic, appreciative one.

Even more stressful for Balanchine than the political situation, suggested a New Yorker article on his Soviet visit, was being back in his homeland and seeing friends and family again whom he had not seen in four decades. Or, pointedly, choosing not to see some of them, because he didn’t want to face the specters of those he’d left. Others, such as his mother and father, he was unable to see because they had died. On his return to the tour in early November after his breather, however, he met more of his family and heard stories of their difficult lives. His own life might have been similarly difficult had he not left. But knowledge of their hardships did not make him kind. Likewise, when he saw that the artists he had known as young and full of promise had become old and beaten, he did not feel increased affection. They appeared to him “old and brown and bent like mushrooms,” and he wondered how you could feel affectionate toward a mushroom.

Balanchine was reticent and stiff even when his brother, a celebrated Soviet musician, played recordings of his own work. As his brother waited at the piano, ready to play more of his compositions for Balanchine’s approval, Balanchine sat with his head in his hands and said nothing. He could not say anything.

I paused in my reading to wonder why the verb was could not, rather than would not. The emphasis with would not is on the desire to resist, whereas could not suggests conflicting desires—the desire to be generous, perhaps, at war with the desire to be truthful. But Balanchine was a showman, and his brother’s display of work was the spectacle. Even mundane shows get some recognition from even disgruntled audiences. Halfhearted clapping is the rule if you are uncomfortable giving a full-blown ovation. But Balanchine, according to a witness, did not respond at all. Why didn’t he applaud his brother?

Quien quiere hace más que quien puede is a Spanish phrase meaning that wanting to do something is more important for achieving it than being able to. The English equivalent is “Where there’s a will, there’s a way.” If Balanchine had wanted to please his brother, the right words would have occurred to him. Instead, he chose to say nothing. In Spanish, people who choose not to struggle, who refuse to engage, often say “Paso,” which is “No way” or “Screw that.” How can you sympathize with a mushroom? The answer is you must want to.

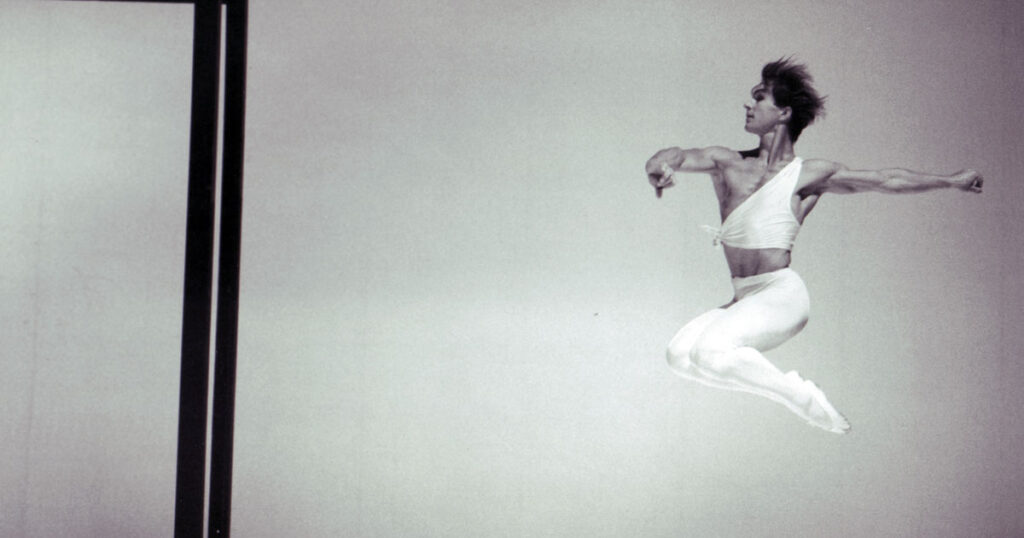

This was in 1962. All these people, with their needs, fears, regrets, and desires, have passed, as a visiting friend from the States said this summer in speaking of some deceased people. It surprised me to hear the euphemism pass from a person of my age and background. The word evokes for me a stage, with a dancer crossing from left to right, steps small and regular, hands fluttering, suggestive of a bird. Onto the stage, then off again, a creature passing into the scene and then passing from it. But under the strong influence of the Spanish verb pasar and its meaning of refusal to engage, I imagine the dancer not fluttering haplessly but sauntering across the stage in a show of studied indifference, giving a dismissive shrug. “Dance? Forget that,” I hear him say. It is a him—it is Balanchine, in the small scene from his homeland visit, refusing to take part. And isn’t that what dying often is—no longer taking part? Bowing out? I wonder that Balanchine didn’t avail himself of the chance with his brother to again demonstrate how to live fully in the moment and, by giving a generous compliment, make his brother a happy man. It would have been a more satisfying performance.

A final note. Exactly 12 months after the Cuban Missile Crisis, the James Bond film From Russia with Love was released in London. The action takes place in Istanbul, with Bond helping a Soviet consular cipher clerk named Tatiana Romanova to defect. Did any of the writers or producers wonder about the implications for the family members Romanova left behind? Or for her emotional confusion at escaping without family? They must not have wanted to. And why would they have? Why complicate a light film with the sad consequences of survival?