My Family’s Siberian Exile

A writer pieces together the forgotten history of life in Stalin’s special settlements

For most of us, Siberia looms as vast and empty in our imagination as it does on the map, but for me, that emptiness has always carried a hint of longing for a past barely remembered. I come from a family of ethnic Ukrainians who numbered among the six million people whom Stalin forcibly relocated to “special settlements,” less restrictive versions of gulag labor camps, in remote reaches of the Soviet Union. My mother, an exile from birth, grew up in Siberia, and it was from there, after my grandparents divorced and my grandfather returned to Ukraine, that she and my grandmother emigrated to Cleveland, where I grew up.

My mother quickly scrubbed away any trace of her heritage, but my grandmother held fast to Ukrainian traditions. The church was the center of her spiritual and social world. Her grasp of English stayed shaky because the women she worked with at a machine factory on the city’s west side had also come from Eastern Europe. She was a constant presence in my childhood and never failed to bring pierogies, stuffed cabbage, or other pungent hallmarks of Ukrainian cuisine when she came by. Only when I got older did we grow close. I discovered that she was a gifted storyteller with a good sense of humor. I admired her work ethic and how much more she cared about people than material things. In college, inspired by the prospect of speaking to her in her native language, I started to learn Ukrainian, and before long, I was traveling to the places that formed the backdrop of her early life.

I spoke to my grandmother extensively about her experiences in exile, slipping a recorder on the table between our mugs of tea. She had been deported from a village near Lviv, Ukraine, at 22, a newlywed with a child by her first husband, who had died during the war. By the time she left Siberia, she had spent almost half of her life there, working in coal mines. When my grandmother died in 2013, at age 88, I worried that a defining chapter of our family’s history was in danger of being forgotten. I envisioned the future whittling her life down to myth: Once upon a time, there was an ancestor of ours who lived in Siberia …

At 31, I was old enough to grasp that my grandmother’s death was not an aberration in the order of things but its true order. I wanted to create a story of her life that would resist oblivion. Although I trusted the essence of her recollections, I knew that time had blurred and distorted her memory. I started searching for information to complement my grandmother’s accounts. But barely anything, in English or Ukrainian, turned up about the circumstances of her exile. I wasn’t the only one in the dark: in the fall of 2017, a Ukrainian political talk show aired a feature on the operation that exiled my grandmother, one of the largest in the country’s history, as its 70th anniversary approached. A survey revealed that about 75 percent of viewers had not heard of the event before the broadcast.

The lacuna did not surprise me. The Soviet regime had suppressed any version of history that deviated from its own, thereby crippling public knowledge of the gulag, the Holocaust, the famine of 1932–33, and other events, large and small, that have shaped Ukrainian life over the past century. Almost three decades after the Soviet Union’s collapse, large gaps in Ukraine’s historical memory remain. Historians’ access to archives increased exponentially starting in 1991, but the former nomenklatura who governed Ukraine after its independence kept classified many documents about sensitive political events during Soviet times.

In the months after my grandmother’s death, this began to change. In early 2014, violence and mass protests resulted in the ouster of Ukraine’s kleptocratic president, Viktor Yanukovych. A Western-backed leader named Petro Poroshenko took his place, and the new administration began expanding the public’s access to those Soviet-era files. Later that year, in the hope of learning more than what my grandmother was able (or willing) to tell me about what had happened to my family, I booked a flight to Ukraine to see what I could discover.

The author’s grandmother (standing, center) with fellow workers at the coal mine she was assigned to during her exile to Yemanzhelinsk, Siberia (courtesy of the author)

Exile as a political tool has a long history in Russia. According to Daniel Beer, author of the 2016 book The House of the Dead: Siberian Exile Under the Tsars and a historian at the University of London, the monarchy, as far back as the mid-17th century, had viewed Siberia, a land of indigenous reindeer herders, fishermen, and nomads, as a “convenient dumping ground for dissidents and subversives.” Between 1801 and the 1917 Russian Revolution, the regime sent more than a million people there, most famously Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Vladimir Lenin, and the Decembrists, who in 1825 attempted to overthrow the monarchy. The tsars’ intent went beyond mere punishment—they wanted to colonize the valuable Siberian landmass for economic gain while morally purifying deportees through hard labor and isolation.

The revolutionaries, eager to distance their movement from a detested feature of tsarist life, abolished exile within two months of assuming power, but they soon found themselves facing the same dilemma: Siberia had valuable commodities and a dearth of workers. Meanwhile, the Bolsheviks had a growing list of people they wanted to marginalize and punish. In 1919, they renewed the practice of exile, adding to it a network of forced-labor camps. By 1930, the Soviets had established a new penal agency to oversee the operation: Glavnoe Upravlenie Lagerei, or Main Camps’ Administration, better known by its abbreviation, gulag.

Under Stalin, the gulag grew so substantially that an estimated 24 million people passed through its institutions during his rule. Exile to special settlements was a fundamental part of the gulag, though it attracts less attention, both public and scholarly, than the more punitive and populous labor camps. Stalin’s first Five-Year Plan, launched in 1928, laid the groundwork for special settlements by calling for the rapid industrialization of what was then still a largely agrarian country. A senior Soviet official introduced the idea of creating “colonization villages” in remote areas that were rich in natural resources such as coal, iron, and timber but unfriendly to human habitation. Middle-class peasants thought to be resistant to collectivization, known as kulaks, were the first unwilling inhabitants of these settlements. In many cases, the peasants arrived to find nothing but a thick swath of taiga, or subarctic forest. “The deportees suffered just as much as their countrymen who had been sent to labor camps, if not more so,” wrote journalist and historian Anne Applebaum in her 2003 book, Gulag: A History. “At least those in camps had a daily bread ration and a place to sleep. Exiles often had neither.” Steven Barnes, a scholar of Russian history at George Mason University, estimates that over the course of Stalin’s rule, more than a million exiles died during the difficult trip east and amid the harsh environment of the settlements.

In the mid-1930s, the regime’s targets shifted. The members of my family were sent away not for being kulaks but because they lived on the fringes of a radical, anti-Soviet variant of Ukrainian nationalism. My grandmother’s elder brother Stefan had been a member of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, the movement’s military arm. He died, according to rumors my family heard later, when a Soviet soldier threw a grenade into the bunker where he was hiding.

The Ukrainian nationalist movement’s allegiances shifted with the political winds—during the war, they initially sided with the Nazis but later made overtures to the Americans. They killed Jews, Poles, and Ukrainians at odds with their aims, often in a brutal, terrorizing fashion. In western Ukraine, where nationalist sentiment was and remains strongest, the movement is remembered less for its atrocities than for its opposition to Soviet power, its most enduring commitment. Of all the nationalist insurgencies that erupted during the chaotic years of the war, the one in Ukraine lasted the longest, costing Soviet forces significant resources and casualties well into the 1950s.

The Soviets retook Ukraine from the Nazis in 1944, and their unsuccessful attempts to quash the uprising led to frustration. “In our work there is one mistake,” said an official at a 1945 conference for Soviet secret police agents held near Lviv, as documented in a declassified conference report. “We kill rebels, we see the rebel lying dead, but each rebel leaves behind a wife, a brother, a sister, and so on.” The secret police designed a mission, dubbed Operation West, to banish family members of suspected combatants to the hinterlands of the Soviet Union. With their families gone, the insurgents would lose crucial support, since their loved ones often sheltered them and hid baskets of food for them in the forest. On October 21, 1947, the Soviets put into motion plans to arrest more than 75,000 Ukrainians they deemed nenadezhnyy, or unreliable. Among the deportees were members of my family, who for countless generations had lived in a village called Staryava, a hamlet in the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains, five miles from the Polish border.

A host of other ethnic groups received the same treatment in the 1930s and ’40s. Some, like the Crimean Tatars, were targeted and removed en masse from their homelands. Other groups—Germans, Poles, Balts, Chechens—were monitored for unreliable elements. Ultimately, between six million and seven million people were subject to internal exile by the Soviets.

After Stalin’s death in 1953, the regime, declaring that there was “no necessity for further maintaining the restrictions in question,” began lifting exile sentences for select groups. By the late 1960s, virtually all exiles, including members of my family, had their sentences canceled. Their freedom came with stringent conditions: exiles, with some exceptions, were not permitted to return to their native communities and received no restitution for property or savings seized by the state after their arrests. Only in the 1990s did the government begin to address the suffering of the exiles, albeit in a limited way. My grandmother’s eldest daughter, Stefa, exiled at age six, receives monthly reparations of 50 hryvnia—less than two dollars—for the 20 years she spent in Siberia. In Ukraine today, that’s enough for two pounds of cherry tomatoes.

Based on what I’d learned from my grandmother and the few secondary sources available, I knew that the Soviets had planned the operation down to the smallest detail: the lists of families to be taken, the secret police and intelligence officers who would make the arrests, the routes for the horse-drawn wagons and railway cars. I decided to travel to Lviv to see if I could find in the newly accessible Soviet files any further information about what had happened to the members of my family who had been caught up in the operation.

Over the years, I had spent stints as long as six months living in Lviv. The city’s mix of baroque, Renaissance, and neoclassical architecture and multitude of church domes, green with oxidation, called up in me the feeling of home. This time, I arrived just as the blossoms that had tumbled from the city’s many flower boxes were being cleared away for the coming winter. Like all Ukrainian cities, Lviv was still shabby from years of paltry public investment, but to me that was part of its charm.

I arranged to stay with Lida, a second cousin a few years younger than me who worked in customer service for one of Ukraine’s cell phone companies. In the 1960s, as the Soviet Union phased out the practice of exile, it permitted a few women and girls from my family to emigrate to the United States. This was a significant victory, given that leaving the Soviet Union was notoriously difficult; the regime couldn’t give the impression that its citizens wanted out. Able-bodied men, however, were a precious commodity after the war, and according to my grandmother, the government held them and their families back. I therefore had an abundance of relatives in the country, most of them clustered around Lviv.

The morning after I arrived, Lida and I set out to meet Alex Dunai, a local genealogical researcher I had hired to help me navigate the city’s holdings. He had cautioned me by email that the new administration’s interest in broadening access to archival material was, like most aspects of Ukrainian government, unpredictable at best. Alex, a cheery, heavyset man in his mid-40s, met us in Lviv’s historic center, and together we made our way up a cobblestone incline to the regional archive of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, where his contacts had suggested we start.

We quickly got an audience with an official at the ministry, a woman whose droopy cheeks accentuated her frown. After we sat down, Alex launched into a description of the documents we were seeking. He kept his hands folded on the table before him. His tone carried a hint of the obsequious. He was good.

The official wrote down the names of my family members and walked out of the room.

We sat alone in her sunny office, listening to the newly bare tree branches tap the windows. Alex explained in a low voice that the ministry was notoriously guarded about its holdings and might not grant me access to the files even if it had them. After a time, I saw a woman with a ream of yellowed documents walking in the same direction the official had gone.

Eventually, the official returned. “We do have documents relating to the individuals you named,” she acknowledged, “but you need to complete an application to receive access to the documents, as well as provide documentation showing your relationship to the subjects in the files.”

“I have my grandmother’s birth certificate,” I said. It wasn’t with me, of course—it was in my desk in Washington. But I had it and kept careful watch over it. My family had few physical items that testified to my grandmother’s life before she came to America.

“Well, all that says is that she was born,” the official said. She explained that I would need to establish that I was my grandmother’s direct descendant by furnishing my mom’s birth certificate, evidence of her marriage to my father, and my own birth certificate, all translated into Ukrainian and notarized.

“Is there a way that I can help?” Lida asked. “Could I write the application and provide the documentation?” The idea made a lot of sense—Lida was at the same remove from the people in the files as I was. The crucial difference was that her documents were in Ukrainian, and she could easily get what we needed from her mother, who lived in a coal-mining town about 45 miles outside Lviv. The official gave us instructions for how to submit the request. That process would take place in a different building across the city.

The three of us walked out onto the sidewalk. Alex lit a clove cigarette. “I will tell you an old joke,” he said. “We used to call the Lubyanka the tallest building in the Soviet Union. Why?” He studied our blank faces for a moment. The Lubyanka was the Moscow headquarters of the KGB, and the notorious site of countless executions and acts of torture. “Because even from its basement, you could see Siberia.”

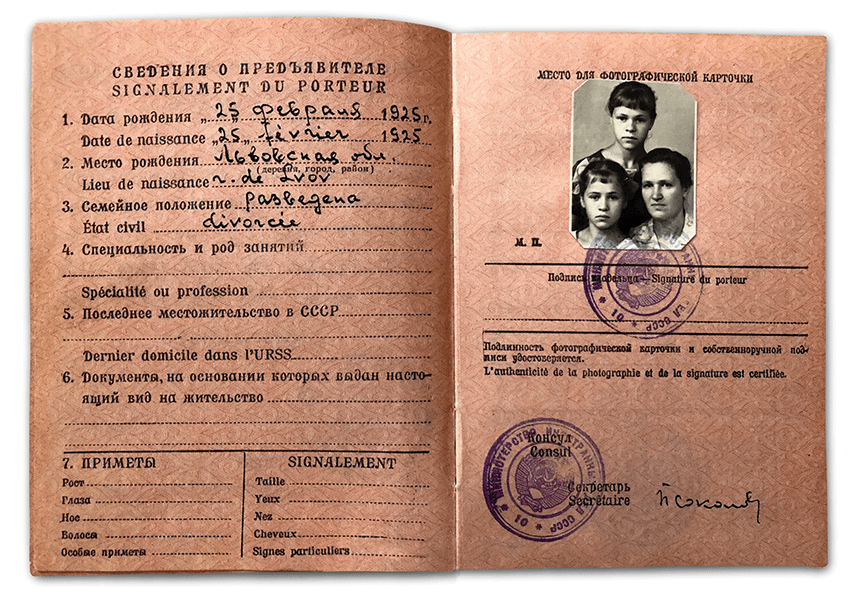

Soviet authorities allowed the author’s grandmother to take her two youngest daughters, pictured with her above, when she left for the United States. (Courtesy of the author)

After phoning her mother, Lida informed me that she could get the documents that day. Her mother paid the driver of a public van, called a marshrutka, that was already heading to Lviv, to take the documents along—a Ukrainian version of a same-day messenger service. Later that afternoon, in a large parking lot on the outskirts of town that reeked of rotten eggs, Lida found the van and retrieved a Ziploc bag containing the documents. “We’re all set,” she said.

Lida filled out a paper request for the files in the waning minutes of the workday. A bureaucrat gazing wearily at a computer monitor said that we’d hear back with the ministry’s decision in seven to 10 days, then added the form to a stack of documents on her desk.

One afternoon, soon after I returned to the United States, my phone started convulsing with text messages from Lida that featured photocopied images of Soviet documents. Her request to view the files had been approved. Altogether, the archive held 147 pages on the exile of my family to Siberia, organized into separate files for each of the adults who had been deported: my grandmother, Anna; my grandfather, Andriy; Rozalia, my great-grandmother; and Ivan, my grandmother’s younger brother. My grandmother’s daughter by her first marriage, Stefa, was so young at the time of the deportation that she did not warrant a file.

That evening, I started to read through them. The files were in Russian, which I spoke poorly but could read competently enough. On the cover of each file, the word secret had been crossed out. As I had hoped, the files strengthened my understanding of my family’s experience, every fact in them a post to support the beams of the story I was trying to build. Together with what I already knew from my grandmother, they helped me piece together a fuller understanding of the events set in motion that October day in 1947.

The soldiers began rounding up the residents of Lviv at 2 A.M. It was cold—in some parts of Ukraine, snowfall hindered the operation. The underground had gotten word that the deportation was imminent, and people who suspected they would be deported had already packed food and clothes. The members of my family, however, were caught unprepared when the police arrived at their modest rural farm, so they did what desperate people do: they ran. My grandmother and Rozalia rushed young Stefa to the fields and crouched in the tall grass, but someone gave them away, and the police pushed them into the horse-drawn wagons with only the clothes on their backs. Ivan hid in a neighbor’s attic, and when the police found him, they beat him. He boarded a wagon with blood flowing from his head. My grandfather had risen early that morning to work in the fields, but somehow the police captured him, too. Family photos, clothing, valuables, official documents—my family members had no choice but to leave everything behind. Later, according to family lore, the Soviets moved their house to a different part of the village and used it as a school.

The wagons took them to a small town called Khyriv, about five miles down the road, where they were transferred to cattle cars, along with about 1,800 other detainees. Some 40 cars, each packed with at least 45 people, lurched into motion, heading slowly east.

The journey was grueling. The passengers were let out for an hour every day or so to get water; sometimes the authorities gave them soup. “Everything happened on those trains—birth, death, everything,” my grandmother’s cousin Slavik, another Operation West deportee from Staryava, told me during my trip to Ukraine. Some detainees tried to escape the trains, but the police recaptured most of them. The passengers called out to people walking along the railroad tracks and asked where they were. The longer the trains rolled on, the fewer Ukrainian speakers they encountered, until at last all they heard was Russian.

On November 4, two weeks after they were arrested, my family members were formally registered in Siberia. They had been relegated to a nascent coal-mining settlement called Yemanzhelinsk in western Siberia. I knew from speaking with my grandmother that within 10 days of their arrival, my grandparents and Ivan had been recast from farmers who tilled the land to miners who toiled beneath it. (Rozalia, then 45, was deemed too old for work.) In her first days underground, my grandmother had been wracked with anxiety as she navigated the dark, narrow tunnels by her headlamp. Early on, she worried that she would not be able to find her way out of the mine, but she soon learned to observe the water running along the sides of the tunnels—it always guided her toward the exit. From the files, I discovered that her mine had a number—18—and that Ivan and my grandfather worked there, too.

My grandparents resided in barrack 3, apartment 13, which they shared with three or four other families. They lived under house arrest, especially during the first few years. “If I had to go to work in the morning, I had to stop by the chief’s barrack. If I went to the market, I had to go and say, ‘I am going to the market for an hour or two,’ ” my grandmother had told me. The exiles had to report to the commander periodically to demonstrate that they were still physically present. In the files, I found sheets of paper on which, at the commander’s insistence, the adults signed their surnames twice a month.

The files also contained a document from May 1950 in which each of the exiled adults attested that they understood that they would be held criminally responsible and sentenced to hard labor if they ever attempted to escape Yemanzhelinsk. The coal mines in which Ivan and my grandparents toiled six days a week did not qualify as “hard labor”—the term was code for the gulag labor camps.

Ivan was sent to such a camp. My grandmother had recounted to me the anguish of her brother’s sudden disappearance. The only thing the settlement authorities told them was that Ivan was no longer in the mine. The sign-in sheets in Ivan’s file go blank starting in September 1951. He was 23 years old, and his wife was pregnant with their first child.

I found six pages in Ivan’s file that detail the case against him and eight other young Ukrainian men. They stood accused of organizing gatherings at which they sang songs glorifying the Ukrainian Insurgent Army; some of the men were charged with trying to aid the army directly. Ivan had been observed giving a toast in honor of the army and all those repressed under the existing government. The authorities noted a second instance, in the summer of 1950, when Ivan “slandered the Soviet regime,” though they did not specify how.

Ivan was tried, found guilty, and sentenced in January 1952. In my grandmother’s telling, the family was able to confirm that Ivan was in a prison only when they persuaded a free Ukrainian girl, who had come to Yemanzhelinsk voluntarily with her boyfriend, to travel to the regional capital and make inquiries. That March, according to Ivan’s file, he was transferred to the Ozerlag labor camp in Irkutsk oblast, more than 1,700 miles east of Yemanzhelinsk. Ozerlag was a large camp designed specifically to hold political prisoners. Inmates there built railroad tracks and logged the abundant larch, pine, and birch of the region’s forests. Ivan, who was eventually able to send and receive mail, wrote to his family about the terrible snow in the winters and the horrendous mosquitoes in the summer. Back in Yemanzhelinsk, the family scraped together what it could in the hope that he could barter for a net to protect his face from insects. In the end, Ivan was lucky—his punishment was reduced during the “thaw” in Soviet repression that followed Stalin’s death. After serving just five years of a 25-year sentence, he returned to his family in Yemanzhelinsk. He was still an exile.

Even with all these new details, there remained aspects about life in Siberia, particularly during the early days under Stalin, that were absent—things I knew only because my grandmother had spoken about them.

The files contain no evidence of how a Soviet official advised my grandmother to put Stefa in a state orphanage because she would be too busy working in the mine to care for her. No record of the fights that broke out over access to the few wells with potable water. No mention of the fleas that infested the barrack or the malaria that scourged the deportees. No hint that the walk from the barrack to the mines took an hour, and often longer in winter’s snow and wind. No documentation of how a miner, like my grandmother, after returning to the barrack from her shift, would often have to go back out to stand in line for the chance to procure a loaf of bread. No indication of how often she would get nothing and return empty-handed.

The files held no trace of how the authorities would arrest starving workers caught stuffing mauled, rotten potatoes into their clothes, claiming even these remnants as “state’s property.” No suggestion that Soviet authorities felt the same about the wood chips left over from construction in the settlement, and that they hunted down deportees who crept outside to steal them because they had nothing to burn, nothing to stave off the cold that froze the buckets of water in their homes at night.

The files included no list of the responsibilities my grandmother had at the mine during the 19 years she worked there—carrying up to 25 pounds of explosives from the staging point to the mine three kilometers away, drilling the explosives into the wall, bracing herself for the explosion, shoveling the ore shards from the freshly crumbled wall into a wagon, helping to push the wagon, laden with up to a ton of ore, toward an electric train that would convey it and its cargo out into the world.

Nowhere was there mention of how, after a mine caved in and crushed those working in it, Soviet authorities joked that with the smaller payroll, “the spoons will be cheaper.”

I couldn’t expect the files to contain the fullness of my grandmother’s experiences, though of course I wanted them to—just as, I suppose, I had hoped that they might somehow bring her back to life. I had been naïve, too, not to think that the files themselves could be used as tools of manipulation. Given Ukraine’s shifting political winds, the power to shape the country’s historical memory now resides with those who see the nationalists my family supported as the noble harbingers of a modern, independent Ukraine. In 2015, at the same time that President Poroshenko approved some of the most permissive guidelines in Europe for public access to records of a deposed Communist regime, he approved legislation that criminalized those who “publicly show contempt” for the nationalist movement.

Historians around the world reacted to the news with dismay. In recent years, scholars have established an abundance of repugnant facts about the nationalists, including their support of the Holocaust and participation in the ethnic cleansing of Poles in a region in northwest Ukraine. With the new law, they worry that future work in this vein may be stymied. Even before the law was passed, some historians accused the Ukrainian government of purposely withholding records that could damage the reputation of the nationalist movement.

I didn’t discuss Ukrainian nationalism extensively with my grandmother, mostly because I was ignorant of the extent of its cruelties. Now I understand that reckoning with my family’s exile to Siberia entails acknowledging their support for the movement. It doesn’t change that they were victims of a repressive regime that denied them their fundamental human rights. But it does introduce a shade of complexity into their story, a shade whose darkness is cast by the pride, anger, ignorance, and fear inherent to nationalism. I treasure the memories I have of my grandmother. I’m grateful that I got to know her as an adult and that she entrusted me with some of the harrowing details of her life. At the same time, I have to remember the context in which they played out. Perhaps, in the end, it’s that complexity that separates history from myth.