My Hairy Past

Shoulder length or longer, my mane was about my looks, yes, but also about the need for justice

When the Beatles appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show for the first time, in 1964, I was about to turn nine and knew nothing about them, although my parents and my six-year-old sister, Anne, somehow did. So did my best friend, John Ruth, who explained that the round things on their guitars—which I had guessed were decorative moons—were control knobs. My ignorance wasn’t permanent. When A Hard Day’s Night came to Kansas City, where we lived, John Ruth and I went to see it more than once, and we watched it the way we watched Dr. No and Goldfinger, by going to the theater without checking the starting times, and staying in our seats until the movie had come back around to where it had been when we sat down. Then, if we had nothing else to do, we let it go around again.

We studied the (tiny) selection of electric guitars in the Sears mail-order catalog and debated about which of them each of us would play in the “singing group” that would make us famous, too. The only friend of ours who ever actually got an electric guitar was Ralph Lewis, whose house was catty-corner to John Ruth’s. One afternoon, Ralph, John, another friend, and I loaded Ralph’s guitar and amplifier into my old Radio Flyer red wagon, rolled everything down the street to my house, and plugged the amplifier into an outlet to the left of our front door. I was wearing jeans and a shiny dark-blue windbreaker, which to me looked like a leather jacket, even though it had a hood. I made my hair seem as long as I could by using my palm to smooth it onto my forehead, then rang the bell, and when my mother opened the door, I gazed (through sunglasses) into her astonished eyes while loudly, tunelessly strumming. This was how we had planned to persuade her that I, too, should have an electric guitar, but the tactic didn’t work.

When I was in kindergarten, my friend Freddy Bartlett used his mother’s electric clippers—with which she gave haircuts to him and his older brother—to shave a parking space on his head for one of his Matchbox cars. Most of the boys I knew in 1964 had haircuts like his (minus the parking space). The closest my friends and I could come to Beatles hair were some beehive-shaped molded-plastic “play wigs”—one blond, one brunette, one redhead—that belonged to Anne and were unpleasant to wear, especially around the ears. Yet even though our real hair was short, we probably looked somewhat more like Beatles when we were not wearing the wigs. My parents occasionally employed a high-school-age babysitter from our neighborhood who preferred the Dave Clark Five, and she said that if you looked closely at any picture of any Beatle, you could tell that his hair wasn’t real. I privately examined my Beatles trading cards, and although I told her she was wrong, there were cards that gave me pause.

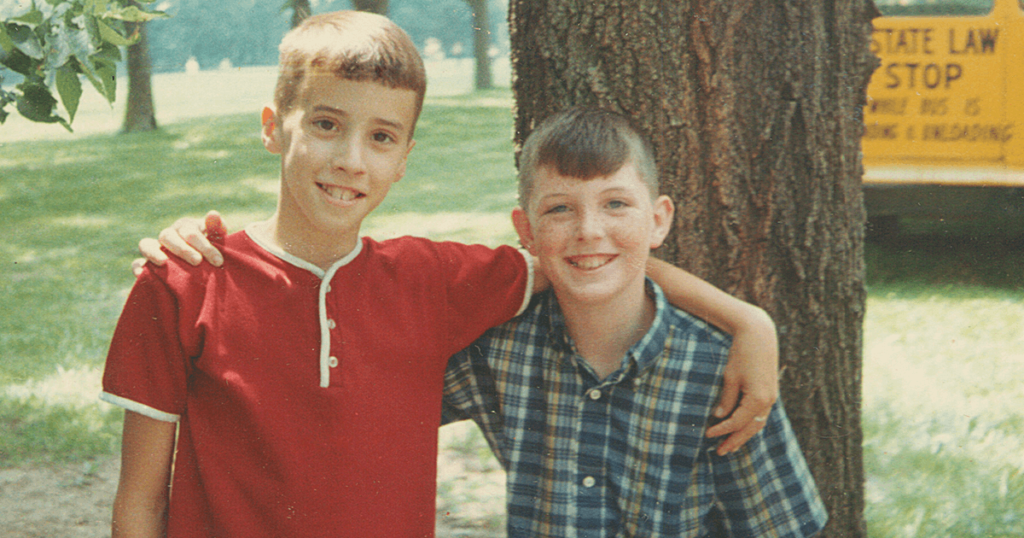

In a photograph of John Ruth and me taken shortly before we boarded the bus for YMCA summer camp that same year, John looks like a miniature army inductee: his head is shaved everywhere except for a small, round clump in front. My own hair by then was slightly longer—partly because of the Beatles, perhaps, but mainly because of Robert Vaughn, who played Napoleon Solo on The Man from U.N.C.L.E. The front portion of Vaughn’s hair formed an adze-like overhang, and I wanted one of those (and also his cleft chin). My father told me that if I regularly combed and parted my hair, as he did, I would eventually “train” it to remain in position. But my hair lacked structural integrity, and it never stayed put. Another problem—this was the era before daily showering—was that while I slept, my hair knotted itself in spiky clumps, mainly on the right side of my head, and I could never get everything flat again before school. I coveted my grandmother’s hairnet, and I once tried sleeping with a tight-fitting plastic mesh bag pulled down to my ears. But doing that made things worse—a foretaste of difficulties to come.

The author and his pals aspired to, but had not yet achieved, Beatles mop tops. (Marc Tielemans/Alamy)

In July 1967, Time published a cover story called “The Hippies: Philosophy of a Subculture,” which I studied in my room. Recently, I bought an old copy of the magazine on eBay and read the article again. It said: “Historically, the hippies go all the way back to the days of Diogenes and the Cynics (curiously, no rock combo has yet taken that name), who were also bearded, dirty and unimpressed with conventional logic.” It said that the hippies “preach altruism and mysticism, honesty, joy and nonviolence” and that they “consider any sort of arithmetic a ‘down trip,’ or boring.” The text was accompanied by many arresting photographs, two of which I remembered clearly: one of some long-haired, bearded guys wearing clothes made from American flags, and one of a hippie girl crouching in front of a primitive-looking hippie dwelling, with nothing on. Reading that article when it came out had made me think that someday I, too, would like to have long hair, a beard, a flag shirt, and a naked girlfriend. I remember exactly where I was—in our Buick station wagon, approaching a stop sign at a particular intersection near our house, on a very sunny day—when I told my mother, based on my reading of Time magazine, that the hippies seemed to have some interesting ideas. At camp that summer in Colorado, a counselor, whose name was Tom Love, lent me a book he recommended, The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran. Another counselor told me later that of all the counselors on the staff, Tom came the closest to being a hippie—a statement I didn’t know how to interpret, because Tom’s hair was no longer than mine.

My hair crept over my ears during the late ’60s, although it didn’t begin to approach hippie length until I was in high school, in the early ’70s. My hair is very fine—it’s almost as soft as cat fur—and when it was at its longest, I could keep it out of my eyes only by sitting still or walking into a breeze. I also had a problem with what my sister was able to identify as split ends—although in some ways the frizziness was useful, because in the more troublesome sections it functioned like rebar. I hesitated to use my hand to move my hair off my forehead, for fear of making the front part greasy, so I leaned slightly to the left and gave my head an occasional snap, to throw it back. My mother, cruelly, recommended bobby pins, and although I scowled at her remark, I privately considered how easy my life would be if I could use them (or her Final Net).

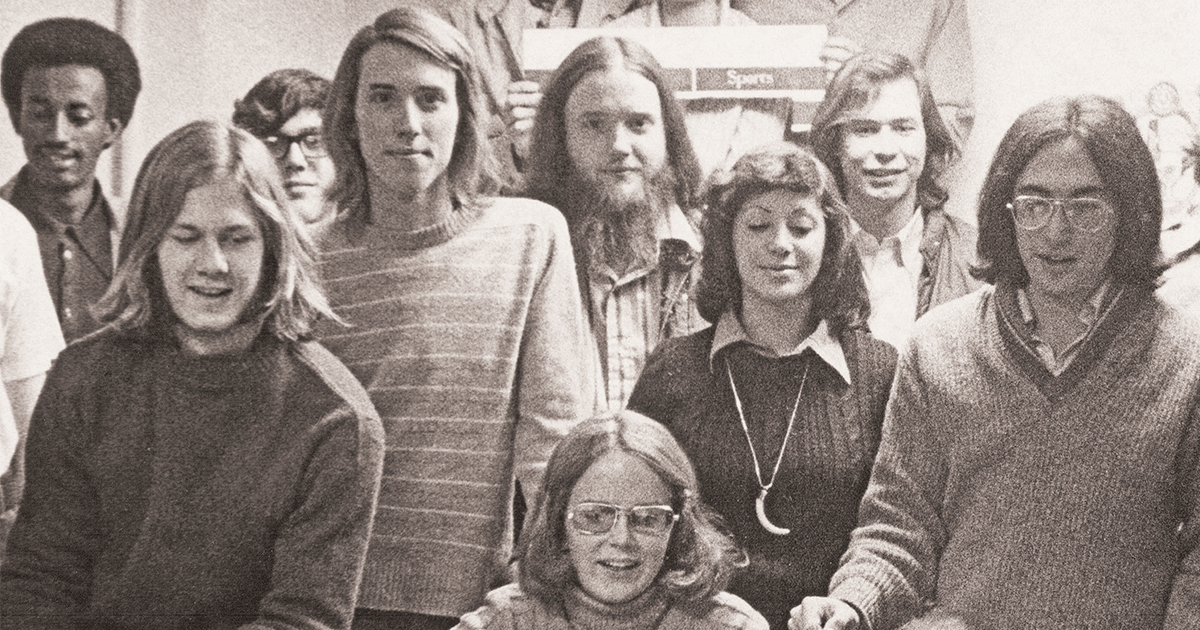

Nevertheless, I liked my hair. In 10th grade, the coach of the track team told me at the beginning of the season that I had to either get it cut or give up pole vaulting, and I quit the team. My school was boys only, and the general rule was that your hair couldn’t touch your shirt collar. That limit was interpreted broadly for a while, and my friends and I had strategies for stretching it further, including tipping our heads forward in the presence of authority figures. Periodically, though, a school administrator or my parents would force me to go to the barber. I would warn the barber to take off no more than “an eighth of an inch, all around,” then grip the arms of the chair and stare at the mirror until he had finished. During a school assembly one morning when I was in 11th grade, the principal, who was new in the job, announced that he was fed up, and he took a pair of scissors from a pocket and told 20 of us to stay behind. Several boys escaped through a window. The incident came to be known as the Hair Purge. I was the editor of the student newspaper, and in the next issue we published a photograph of the principal examining the back of the head of my friend Henry, who now has very little hair but then had quite a lot. We also published a letter from a man who was a teacher and a member of the school’s board of trustees. In the letter he described the Hair Purge as “degrading beyond belief” and “one of the saddest, most humiliating scenes” he had witnessed in his 12 years at the school.

That letter made me happy, although even at the time it struck me as an overreaction. Then the principal overreacted, too. He suspended me from the newspaper, on the grounds that I had failed to give anyone an opportunity to censor the letter, and he did so over the contrary recommendation of the Discipline Committee, of which I was a member but from which I had had to recuse myself for this, our first case ever. I remember reading somewhere that, to an adolescent, the paramount moral issue is fairness. My suspension must have seared a permanent lesion in the fairness node of some primitive part of my brain, because today that principal is the person at whom, by several decades, I’ve stayed angry the longest. In 1985, my wife and I and our daughter, who was a year old, moved from Manhattan to a small town in Connecticut about 90 miles north of the city, but we almost moved to a small town in New York State about the same distance away. I learned later that the head of one of the New York town’s schools, which our daughter might have attended, eventually, if we had moved there instead, was my old high school principal from Kansas City. We’d have had to move again.

The principal and Henry during the Hair Purge. (Courtesy of the author)

An argument that teachers, coaches, parents, and others made against long hair was that boys who had it not only looked like girls but also, inevitably, used drugs. My friends and I objected that this was an example of post hoc reasoning, which in some class or other we had learned to eschew, but in fact, as we ourselves knew, the correlation was more than accidental, and one of the things I’d found compelling in the Time article—although I hadn’t mentioned this to my mother—was its discussion of mind-altering substances. The article said that a drug called marijuana (“the green-flowered cannabis herb that has been turning man on since time immemorial”) was “ubiquitous and easily grown, can be smoked in ‘joints’ (cigarettes), baked into cookies or brewed in tea (‘pot likker’).” It also said, “Defenders of the hippie subculture liken it to a super-Eucharistic ritual, one that has brought drug users, particularly of LSD (‘the mind detergent’) and other synthetic hallucinogens, into epistemological experience and thus changed their lives forever.”

The idea that your understanding of the world could be transformed by something you smoked or swallowed seemed more startling to me in 1967 than it possibly can to anyone nowadays. An occasional sleepover activity with my friends when we were younger had been hyperventilating, which took you to the tingly edge of unconsciousness. The drugs favored by the hippies, I inferred, induced a similar condition, but for longer periods. When I was in eighth grade, in the bedroom of my friend Duncan, several of us tried chemically assisted hyperventilation by spraying Arrid Extra Dry through socks held over our mouths and inhaling deeply. When a friend’s older sister learned what we’d been up to, she was so horrified that she began supplying us with marijuana.

Later that summer, in a park in our neighborhood, Duncan produced an envelope containing what he said was LSD, and five of us each swallowed a crumb-size orange piece. I don’t think I expected anything to happen, but after 30 minutes or an hour, I realized that I was minutely examining a sun-bleached dog turd in the grass where we were lying, and began to wonder. Most of the rest of that afternoon, evening, and night consisted for me of confusion, anxiety, and intense paranoia, punctuated by (admittedly) impressive perceptual effects, including a cartoonlike animation that played on the interior surface of my eyelids when I closed my eyes.

Everyone I knew seemed to handle reality altering better than I did. One night in high school, my girlfriend and I knelt in the back seat of a friend’s car and looked out the rear window, laughing, while the friend drove backward down a roller coaster–like county road in rural Missouri. He assured us that we were safe because he wasn’t drunk but “just tripping,” and I remember feeling not afraid or reckless but abashed by the certainty that if I had been in his condition, I would have been too overwhelmed to steer straight. Another evening, the same girlfriend and I took some mescaline that I had bought at school, and although it wasn’t very strong, I became hopelessly lost in the narrative complexity of the television program Love, American Style, which we were watching on a small black-and-white TV. (A complicating factor was that each episode consisted of multiple unrelated mini-episodes featuring many of the same actors. I was as baffled as I later was by Finnegans Wake.) A tenet of hippie thinking was that hallucinogens are windows on the soul—a grim notion, as far as I was concerned, since my own soul, based on what I had glimpsed of it, appeared to consist mainly of confusion, cravenness, and dread.

The hirsute author in striped sweater during his college years. (Courtesy of the author)

During the summer after eighth grade, which was also the summer of Woodstock, my friends and I began attending rock concerts at Memorial Hall in Kansas City, Kansas—beginning with Vanilla Fudge and including, eventually, Steppenwolf, Jefferson Airplane, Led Zeppelin, Janis Joplin, and the Grateful Dead. I wore bell-bottoms and, when I thought of it, lifted my shoulders a little, to make my hair seem longer. In May 1970, a new concert hall, called Freedom Palace, opened closer to where we lived, in a building that when my parents were teenagers had contained an enormous dance floor mounted on steel springs. (The building had also had an ice rink, and when my grandmother came to pick up my mother after a skating party there in the 1940s, she embarrassed her daughter by placing a package of lamb chops on the ice to keep them cold while she waited.) Tickets for Freedom Palace shows cost as much as $3.50, and you could buy them at Tiny Tim’s Magic Circus, where you could also shop for rolling papers, water pipes, roach clips, and edible body oil, among other hippie staples. We went to the inaugural show, by Canned Heat, and to many shows after that. We saw The Who on a typically suffocating Kansas City July evening in 1970. Hundreds of counterfeit tickets had been sold, and the building either wasn’t air-conditioned or wasn’t air-conditioned enough. The power kept going out. Roger Daltrey angrily threw a microphone at the wall behind the stage. People standing in the balcony near the concession stand threw ice into the swelter below. Ten or 15 feet ahead of us, two long-haired girls, who were only a little bit older than we were, took off their shirts.

Even in 1970, the name Freedom Palace seemed slightly ridiculous, but the impulse behind it was something I had come to understand and believe in. Electric guitars, illegal drugs, and long hair had evolved into political and moral arguments against the depravity—against the essential unfairness—of the horror-filled world of adults, which at that point was presided over by Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew. (Freedom Palace opened four days after the Ohio National Guard fired on unarmed students at Kent State University.) Among the many things that surprised me about Time’s hippie article, when I read it again, is that it contained no mention of Vietnam, other than an observation that hippies “feel ‘up tight’ (tense and frightened) about many disparate things—from sex to the draft.” Maybe the editors didn’t perceive a connection, or did but dismissed it as unworthy of discussion, since at that point the magazine’s position was virtually indistinguishable from Lyndon B. Johnson’s, Robert McNamara’s, and my father’s. By the time Freedom Palace opened, cutting your hair could feel like an endorsement of evil; John Lennon (whose hair was exactly what I wanted mine to be) was a far more appealing moral exemplar than any of the usual candidates, Yoko Ono notwithstanding. Grownups missed the point about long hair when they triumphantly pointed out that the so-called nonconformists sure looked an awful lot alike. Recently, my mother, who is almost 90, told me that she and a friend had been discussing the old hair confrontations. “Why were we so upset?” she asked. “It wasn’t like you wanted tattoos.” But of course, if no one had been upset, it would have had to be something else. Maybe even tattoos.

In 1983, on a reporting assignment, I joined 67 American Beatles fanatics on an organized tour of London and Liverpool. We visited Abbey Road, Penny Lane, Strawberry Field, the site of the old Cavern Club, and other landmarks, and we met Liverpudlians who had known John Lennon, or said they had. One of the women on the trip swore she wouldn’t leave England until she had met at least Ringo, and a few weeks later she mailed me a photograph of herself standing on a sidewalk in London with Paul McCartney. I myself met McCartney 18 years later, in Paris. By that time, his hair and mine were approximately the same length, although mine had more visible gray. I was working on an article about his daughter Stella, the fashion designer, and after he’d answered my questions about her, I mentioned my own children and said I’d often walked past their bedroom doors and heard them inside playing 35-year-old Beatles songs on their electric guitars (ahem).

My son, whose name is John, didn’t get just the electric guitar I’d once wanted; he also got the hair. He grew it long in grade school and again in high school, and it stayed out of his eyes all by itself, among other remarkable features. I often worried that I had somehow willed him to want long hair, for my vicarious benefit—or that my wife had, since she seemed to be at least as interested in it as he was. We influence our children in elusive, insidious ways—or maybe we don’t. At any rate, I had a complicated emotional reaction when the head of his school demanded that he get it cut or face consequences. Thirty years of reflection and life experience had deepened my feelings about the power of idealism, and—to the dismay of everyone else in my family—I took the side of the school. There was much angry shouting in our house that evening. But in the end I prevailed. The barbershop had closed by then, but I reached the barber at home, and she agreed to see John there. She cut his hair, to shirt-collar length, in an old barber chair in her basement, and the next morning he was allowed to take the PSAT.

The following fall, John wrote a long, tightly reasoned letter to his school’s administrators in which he argued that it was unfair to treat boys’ hair differently from girls’—and he made his case so well that, remarkably, they changed the rule. It was the kind of victory I had yearned for in high school but hadn’t believed was possible, and by the time John went to college he had the ponytail of his father’s dreams. When he got there, however, he noticed that few other students had hair as long as his—and as my wife and I were helping him move in, I noticed the same thing. Long hair had no meaning then; it was just a style, and an anachronistic one, at that. Not long afterward, in a bookstore, a neo-hippie girl spotted John’s hair from the back and mistook him for someone else, a neo-hippie boy who, for spare change, often performed in a public square near the campus. “Hey, Juggler Man,” she said as she came up behind him. And the next day he got it all cut off.