My Mongolian Spot

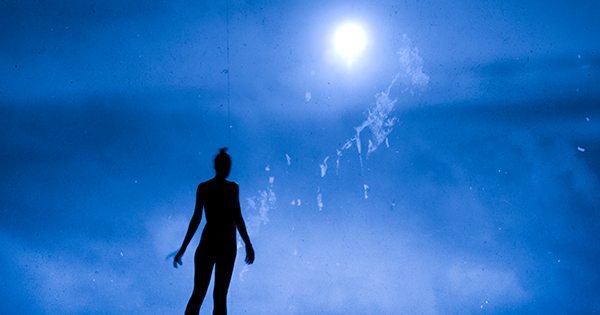

An ephemeral birthmark is a rare gift, connecting me to generations spanning the centuries

First you should know: I was born with a blue butt.

So was my mother.

Thirty-two years and many thousands of miles of land, sky, and sea separated her creation from mine, yet we emerged the same: wailing, mad for first breaths,

10-fingered, 10-toed, chick-like tufts of black hair nested atop our soft skulls, and, incredibly, a wavy-bordered blue spot not unlike that of Rorschach’s inkblots, blooming across our tiny bums—blue like ice-cold lips, blue like the ocean at midnight, Picasso’s most melancholic bluest of blues.

By the time I learned about my blue butt, it was gone. Like a spy’s secret message written in vanishing ink, the spot disappeared sometime after my fourth birthday. The timing seems strange—to think that as soon as I could form my earliest memories, my blueness had already left me. In one such memory, I recall taking a shower with my mother. The water beat down on my shoulders thunderously. I’d misbehaved (perhaps, refused to wash my hair), and as I slid open the mottled glass door to escape, my mother smacked my bottom. Because this is my earliest butt-related memory, I mined it recently, hoping to uncover any clues of my former blue self. I remember wailing in the showy way children do when they’re old enough to know better, then peering behind me for proof: the fierce, fiery outline of my mother’s hand. But I can recall nothing but plain tush. I was neither red nor blue. We stood as nude as newborns, un-shy in our nakedness, water cascading across my mother’s towering body as she fumed and I wept in her shadow.

I once asked my mother why we were born blue, and she said matter-of-factly, “Because we have Mongolian blood.” Then she walked away casual-like, as if such a spurious-sounding answer did not inspire its own army of follow-up inquiries. My parents were born in South Korea, but I was born in Los Angeles, raised in a nowheresville suburb on frozen TV dinners and laugh-track sitcoms. Jennifers were American. I was American. My blue butt and Mongolian goods seemed practically mythological.

But I wasn’t alone. My older sister Laurie was also born blue, and her marking lasted well through kindergarten. We know this because Laurie’s teacher asked my mother to come to class one day for an emergency conference. The teacher had taken Laurie to the bathroom, seen her blue butt, and mistaken the spot for an enormous bruise. When my mother told me this story, more than a decade had passed, but the encounter still annoyed her—not for the absurdity of the accusation so much as for the teacher’s ignorance. “We are Korean,” my mother explained, as if forced to qualify that the grass was green, or that birds could fly. “We are all born this way.”

I didn’t believe her until I saw a blue butt for myself. After my aunt gave birth to a boy, my mother and I visited to coo over the baby. When it was time to change his diaper, my aunt plucked him up by his ankles, folded his little naked body, and there it was: a bona fide blue butt in the flesh. I felt oddly proud at the sight of it. We were all part of the same club, our secret selves hidden from the rest of world.

My mother pursed her lips at me, as if to say, “See? Told you.” But I was too distracted by the striking shade of blue before me. Not happy or cheery, but deeply dark hued. A kind of sorrowful inheritance.

When my mother told me about our purported Mongolian blood, I was 14 years old. The most I’d heard about Mongolia back then pertained to the Khans, namely Kublai and Genghis, the latter at best known as the founder of the Mongol Empire and at worst considered a genocidal warlord. In the 13th century, all of East Asia had been seized through countless Mongol invasions, in a reigning fiefdom that eventually sprawled as far as central Europe, Indochina, India, and the Iranian plateau, so it’s true my family’s history is inexorably tied up in that messy business. Still, it seemed depressing to think how all that remained of the largest contiguous land empire in human history were these vanishing blue butts—and a stir-fry joint in our local shopping mall’s food court.

At Great Khan’s Mongolian Festival, you picked all the veg and meat toppings you wanted, which were then cooked with chewy yellow noodles right in front of you on a round, flattop plancha grill. Talk about a fall from grace. The signage had jaunty script, illuminated in primary-colored neon, reminiscent of an entrance to a theme park ride, and the mascot was a mischievously grinning, side-eye-glancing Mongolian warrior, with wispy facial hair, crossed double swords, and that iconic horned helmet. I did not order here often—doing so inspired a specific breed of guilt. The mascot at Panda Express was an innocuous cartoon bear, yet here I was bankrolling a caricature I knew inherently to abhor. But rather than fessing up to my own fraudulence, I let my mind be empty, and chose instead to monitor the simple tactility of my order’s progress, which usually entailed a Mexican dude sautéing my food with a pair of comically oversize chopsticks. Or I could watch the blondies across the way at Hot Dog on a Stick, in their cheery uniforms and shako caps, pumping vat after vat of 100 percent fresh-squeezed, real lemonade.

Mongolian blood aside, my mother to this day enjoys reminding me that I am “100 percent Korean.” She thinks this purity is a gift, says so with immodest superiority, the way some people talk about 100 percent Egyptian cotton sheets. But in a rather complicated twist, my paternal grandmother, a Choi, was raised in Manchuria. That area is now largely referred to as Northeast China, but also happens to include parts of modern Mongolia. To our knowledge, she never lived in a yurt, or ger, as native Mongolians call them. Neither did she dine on marmot meat, or ride horses, or extract alcohol from goat’s yogurt, as some rural Mongolians do. My grandmother, a learned woman, said to be “ahead of her time,” studied philosophy in Tokyo and theology in Connecticut. She did not wear an ornate horned helmet. We do not know what region of Manchuria she lived in, whether she encountered Mongolians, or, for that matter, whether she considered herself Mongolian too, in spirit or by blood. But she was born bearing the legendary, budding blue that links us all.

According to Korean folklore, our blue spots derive from Samshin Halmoni, Grandmother Spirit, a deity whom many families prayed to for their unborn child’s good health. Samshin slaps children to life when they are born, leaving behind the indelible blue spot. In other derivations, Samshin beats the baby blue, until it is forced from the womb.

Science tells us that melanin-containing cells trapped in the deeper dermis during embryonic development cause our strange coloring. The result is a blue birthmark, often found on the bottoms of East Asian babies, that dissipates by age five. Western medicine classifies the blue butt as “congenital dermal melanocytosis,” or in common parlance, the Mongolian spot. A German doctor named Erwin Bälz coined the term in 1883. Bälz “discovered” blue butts on Japanese babies while serving as personal physician to Emperor Meiji and the Japanese imperial household. Our blueness existed far before 1883, though not in the world of white men, and so it goes.

But if the babies were Japanese, why did Bälz deem them Mongolian? The landlocked nation of Mongolia did not yet exist the way we know it today; it hadn’t even acquired independence from the Manchu, or Qing, dynasty.

It just so happens that the Mongolian that Bälz referred to was not ethnic but taxonomic. To understand this fully, we must traverse backward and west, to 18th-century German scholar Johann Friedrich Blumenbach. In a later edition of his 1775 work, On the Natural Variety of Mankind, Blumenbach divided the human species into five definitive categories: the Caucasian or white race, the Malayan or brown race, the Ethiopian or black race, the American or red race, and the Mongolian or yellow race. Blumenbach determined these classifications based on his expansive collection of skulls, gathered from around the world. Beyond this private interest and study, no scientific proof supported his naming system. Blumenbach’s races were as improvised and subjective as any other made-up name.

I suppose these kinds of enduring choices last, however apocryphal the origin, because people rely on the certitude of names. Sometimes we base this knowledge on one man’s personal opinion. Sometimes we call that process science.

According to archaeological findings, my skull type, that of the Mongoloid variety, existed as far back as 10,000 years ago. Physical anthropologist Carleton Coon wrote in his 1962 book, The Origin of Races, that my ancestors, the Mongoloid subspecies, existed throughout most of the Pleistocene era, which ended about 11,700 years ago.

If you’re like me, you might be alarmed by the word Mongoloid. Set that aside for the moment, and consider this: science tells us that Mongoloid is merely another suitable classification we ought to accept for the Asian race.

It is unclear when Mongolian and Mongoloid fused into synonymous taxonomic foils, but most credit Blumenbach for the origin of both terms. Their casual interchangeability is rampant across early ethnological texts. A three-race model, popularized in the 1940s, is still employed by some forensic anthropologists today. It features the Mongoloid in an achingly archaic trio alongside Caucasoid and Negroid. Like the Mongolian, the Mongoloid includes populations from East, Central, and Southeast Asia, as well as eastern Russia, the Arctic, the Americas, some of the Pacific Islands, and northeastern sections of South Asia.

One might consider this lumping together of visible minorities an example of what Swedish botanist and zoologist Carl Linnaeus called a wastebasket taxon, also known as wastebin, dustbin, or catch-all taxon—a term to classify organisms that do not fit into any other preexisting category, a taxonomical junk drawer, if you will.

Supposed physical features of the anthropological Mongoloid, compiled from Stanford’s Compendium of Geography and Travel for General Reading (1882), American Journal of Physical Anthropology (1939), Mapping Mongolia: Situating Mongolia in the World from Geologic Time to the Present (2011), and Forensic Facial Reconstruction (2004):

• Thick skin cuticle and an abundance of carotene; yellowish complexion.

• Lightly oblique eyes, small nose, black lank hair, sparse beard, salient cheek bones.

• Glabrousness, i.e., little or no facial or body hair. According to Carleton Coon, both “Negroid and Mongoloid skin conditions are inimical to excessive hair development except upon the scalp.”

• Upon the scalp, hair is coarse, straight, blue-black and weighs the most among the races.

• Possesses 450 sweat glands per square inch of skin; both “American blacks” and Caucasoids possess 750 sweat glands per square inch.

• Relatively broad, flat faces; absent brow ridges.

• Upper eyelid characterized by puffiness, extra fat, and the epicanthic, or “Mongolian” fold (the skin fold on the upper eyelid that covers the inner angle of the eye, which creates the Asian “almond-shape”).

• Gracile skulls due to the Mongoloid’s very recent evolutionary development.

• The “Mongolian spot.”

Physical features present in my family, and other observations:

• The “Mongolian spot.”

• I have never seen my father sport a beard. I don’t think he can grow one. His legs, arms, and chest are completely hairless. He combs the plentiful, strong hair on his head definitively to the right.

• Until we entered a sauna, I had never seen my mother sweat.

• When I was a child, my mother told me I was lucky, because I’d been born with big eyes. But some days at recess, my classmates pulled the corners of their eyes back so that their prismatic green or blue pupils disappeared behind taut slits of skin. They said, pleased, Look, I’m you! Once, perplexed by their game, I retreated into the bathroom to examine my reflection. I studied every crease and curve, as if beneath the lens of a microscope, for any indication of the grotesque mask they’d presented me. I returned to class believing my eyes were not slanted but broken, for I could not seem to see what they could.

• The back of my grandfather’s skull is as flat as a woodblock. His head is shaped this way because he was a chak-heh baby. Back in rural prewar Korea, “sweet babies” did not squirm when you laid them down but remained obedient and still, so still their supple skulls flattened to the earth. This was a favorable trait in his day, a lifelong indication of one’s goodness. The clear verticality of my grandfather’s profile is, to me, his finest feature, the kind of bare elegance you might find in the clean lines of a half moon in the night sky, or the smooth horizon at sunset. When I was a baby, my mother laid me on my face to sleep. She wanted my skull to be round. She wanted my skull to be beautiful.

In his study of craniometry, Blumenbach believed the Caucasian skull to be the utmost superior in physical beauty—the flawless benchmark from which all other races diverged. Blumenbach also concluded that man originated from the Caucasus Mountains, the stunning terrain where Noah’s Ark supposedly came to rest. The skull Blumenbach examined for his findings had actually belonged to a Georgian woman, but he chose to propagate the broader term Caucasian for his perfect race instead. He did not, however, conceive of that name. The first appearance of Caucasian can be traced to a 1785 publication, The Outline of History of Mankind, written by Christoph Meiners, a colleague of Blumenbach’s at the University of Göttingen and a fellow German philosopher.

Meiners divided humanity into two categories: the beautiful race and the ugly race. The beautiful Tartar-Caucasians were light-skinned, “gifted in spirit and rich in virtue,” whereas the Mongolians, the dark-skinned, ugly race, exhibited weakness in body and spirit, and deserved to be controlled through despotic rule.

No actual science had ever upheld Meiners’s racial hierarchy. Subjective beauty served as the essential, and only, criterion. In her 2010 book The History of White People, historian Nell Irvin Painter details the questionable nature of Meiners’s politics; he merely relied on selective ethnocentric travel literature to inform his narrow theories. I recently stumbled upon a portrait painting of Meiners and was surprised to find in his face an uncomely asymmetry: knobby, ruddy nose; meaty, wide brow; thin, flaccid lips. To me, only in the most charitable conditions could he be categorized as “beautiful.”

Thankfully, today, Meiners and his written works are all but forgotten. The legacy of his colleague, Blumenbach, however, often referred to as the Father of Scientific Anthropology, appears everlasting. His Caucasian has seamlessly entered our modern lexicon, and we utter the word, oblivious to its arbitrary origins, amenable to its superior beauty, unknowingly acceptant, too, of its ugly Mongolian twin.

In Korean, the word for America is Miguk, meaning “Beautiful Country.” My maternal grandmother, a Bahk, is of the post–Korean War generation that believes everything Made in the U.S.A. is superior. She wants Skippy peanut butter shipped from the States to Seoul even though she can find it in her neighboring town’s E-Mart, a most epic grocery store that trumps all other grocery stores. Besides Skippy, E-Mart sells artisanal earthen cookware, age-defying face emulsions sourced from rare snail slime, fine rice wine, and perfectly ripe watermelons accompanied by well-engineered, complimentary straw satchels. To her, certain things Koreans still do best: kimchi, cars, electronics. But she has a habit of flipping over any packaged good to inspect its origins. “Ah,” she’ll say, pointing to the label, relieved. “Yoo-essuh-aye. Numba one.”

When I graduated high school, this same grandmother offered me the chance to change my eyes. Double-eyelid surgery, or Asian blepharoplasty, all the rage in Seoul, is a cosmetic operation that reshapes the skin around the eye. Many Asians, like myself, are born with a monolid, meaning there is no natural crease above the lash-line. Asian blepharoplasty removes upper eyelid fat, and after a new crease is stitched in to the lid, the eye appears bigger, rounder, and to some, more attractive.

Perhaps my grandmother wanted me to look round-eyed for the same reason she cautioned me against suntanned skin, or why she often permed her own black lank hair. She did not consider herself part of an inferior, ugly race, but it seems she ever aspired to revise her body and mine, according to some extrinsic standard I could not then easily comprehend.

Still, for as long as I’ve been alive, whenever my grandmother looks at me, monolids and all, she does not see someone from Asia. I may have inherited her bridgeless nose or gracile skull, but to her I have always belonged to a different, superior stock. To her, my mother is Korean, but I am a Miguk saram, American: the one from Beautiful Country.

Across the pond, in Surrey, England, on the sprawling, wooded acreage of Earlswood Asylum for Idiots and Imbeciles, Dr. John Langdon Down once conducted a curious research. Down, who served as medical superintendent, believed in a natural system of classifying the “feeble-minded,” based on how their facial features best resembled Blumenbach’s five races. He published his conclusions in an 1866 study, Observations on an Ethnic Classification of Idiots. In it, Down deduced that some patients’ disabilities rendered them more akin to those who resembled “the great Caucasian family”; there were also “several well-marked examples of the Ethiopian [i.e. African] variety,” those of “the Malay variety,” and those resembling “people who … originally inhabited the American Continent.” But Down devoted particular attention to what he deemed the “Mongolian type of idiocy.” Certain European patients possessed slanted eyes, accentuated by epicanthic folds, an irrefutable characteristic of the Mongolian race.

After years of genetic research, Down’s Mongolian discovery would earn a proper name: Trisomy 21. Those born with Trisomy 21 possess all or part of a third copy of chromosome 21, rather than the usual two. Today, we know this by a different name: Down syndrome. But for more than a century, doctors, patients, and scholars all referred to the condition as “mongolism,” or “Mongolian imbecility,” in other words, the Asian type of idiocy.

Some argue that Down never referred to his Mongolian idiots as mongoloids, but our current, pejorative understanding of the term most certainly emerged from his work. Just as well, Down did not imply that those afflicted with mongolism appeared objectively unattractive; still, we have since come to associate such features with an undesirable mental condition.

So those, unlike me, who opt for Asian blepharoplasty can altogether eliminate that undesirable, Mongoloid quality from their eyes, the Asianness from the Asian eye via a simultaneous epicanthoplasty, which removes our tainted epicanthic folds. According to Los Angeles plastic surgeon Kenneth Kim, Asians with a “harsher appearance” will experience, post-surgery, a “softer, more open look.” I examined a few corresponding photos on his website, and couldn’t help but agree; the “After” women looked far more beautiful, energetic, kind. It occurred to me that to the world, I might resemble some walking “Before” photo: tired, mean, or worse—“feeble-minded.” Perhaps my grandmother had hoped to repair me of this. It’s possible, too, that every Asian eye surgery is a kindred, unconscious act, to excise that which binds us to our slant-eyed, blue-bummed Mongolian past.

There are mongols, and there are mongols.

An entire century lapsed before anyone objected to the inevitable discrepancy between Down’s ethnic idiot and the East-Central Asian group native to the nation of Mongolia.

In 1961, the prestigious British scientific journal The Lancet agreed to call the condition a new name—Down syndrome—because the increased participation of Chinese and Japanese scientists “impose[d] on them the use of an embarrassing term.” But the change received considerable opposition. To commemorate the centennial of Down’s landmark paper, several specialists met in London in 1966. Controversy over the disorder’s name sparked debate, as this transcript offers:

Dr. Cummins: Objections have been raised against the [terms] “mongolism,” “mongol,” and “mongoloid” because it is said that they resurrect the idea of racial affinity. I think this is an imagined difficulty. We use many terms containing embalmed errors from the past. The words “aorta” and “artery” never arouse in us thoughts of these vessels as air tubes as it was with the ancients; we just use the words as words. And the same applies to the word mongolism.

Dr. Matsunaga: I am not happy with the words mongol, mongolism, and mongoloid, although I agree that they are convenient to use. The basic question is this: is it ever justified in medical terminology to misapply a name, especially a geographical one, to a disease when this name becomes inappropriate because of increased understanding of the underlying pathology?

Dr. Penrose: I use the term mongol and have taken refuge from the accusation of racial discrimination because the Down-syndrome type of mongol is not spelt with a capital letter whereas the racial type of Mongol is.

An imagined difficulty. Recently, I performed a Google search of mongol, which reaped very real, unsettling results, from cruel British schoolyard slang to Uuganaa Ramsay’s story. A decade after scientists were arguing over semantics, a young woman named Uuganaa lived inside her family’s Mongolian yurt. Unlike my paternal grandmother, Uuganaa cooked marmot meat over open fires, traveled on horseback, distilled vodka from fermented yogurt. Her family wore sheepskin-lined deels to keep warm and used sun-dried cowpats for fuel. I think she studied English because she wanted to belong to the modern world. When she paged through a dictionary to find the word Mongol, the primary definition described a man or woman whose patronage traces to Mongolia. The secondary definition: a person with Down syndrome or the mentally ill.

I have used the term mongol and have taken refuge. According to her 2014 memoir entitled Mongol, Uuganaa eventually moved to Great Britain, where she married a Scotsman and gave birth to two children. Her second child, Billy, was born in 2009, sporting the blue Mongolian spot. But Billy also possessed an extra chromosome, characteristic of Trisomy 21. Devastated by his prognosis, Uuganaa and her husband sought solace from their doctor, but he suggested that Billy’s disability might not be physically noticeable, given Uuganaa’s ethnic background. In other words, a Mongol is a mongol, capitalized or not.

Embalmed errors from the past. A year later, in 2011, British comedian Ricky Gervais casually tweeted to his scads of followers a series of puns and jeers: “Two mongs don’t make a right,” “Good monging,” “Night night monglets.” The nonprofit organization Down’s Syndrome Scotland scolded Gervais in a public statement; his frivolous use of mongol derivatives appeared irresponsible, and callous to those with learning disabilities. But to Gervais, a mong is a generic term for a div, a dummy, an idiot, devoid of its former implications to Down syndrome. Gervais elaborated in his own statement: “I clearly explain that words change. … Not only am I not referring to people with Down’s syndrome, I also explain that I am not associating the word with its old derogatory meaning.”

Words change. We forget the mongoloid was first Asian. Or how a tiny fold in the eyelid transformed the Asian into imbecile. Gervais had it wrong, though. There is no dissociating a word fully from its old meaning. It might disappear from the surface, like our blueness, but the essence remains, an entombed truth, our indisputable origin.

Or maybe the words don’t change at all—we do.

My mother says there is no Korean word for our blueness. Perhaps this is based on the same principle that applies to French doors or Dutch ovens. In France, glass paneled doors are known as portes-fenêtres, or door-windows. In the Netherlands, a “Dutch oven” is called a braadpan, which is used on the stove to fry meat. Maybe, to Koreans, our blueness is not unusual. Our butts are just butts.

Still, if I ever have a child, I will tell her about our shared mythos. I’ll say that she might have the gift of Mongolian blood coursing through her tiny core, like my mother’s, like mine. Or how Samshin Halmoni may have slapped her blue, to life. At some point she might want to alter her eyes, her skin, the essence of her being, which is why our blue period lasts much longer than four brief years. In the impossible void where words and science have failed us, I want her to know that being born blue is exceptional, some magic in our chemistry, a bright and bruised and blooming sign that says, if only to each other, we belong. And though she might feel otherwise, I hope she learns that it is not her responsibility to stay easily defined. Some things, like being blue, are meant to remain ineffable, impermanent, unnamable, unnamed.