New World Prophecy

Dvořák once predicted that American classical music would be rooted in the black vernacular. Why, then, has the field remained so white?

Listen to Joseph Horowitz and Sudip Bose discuss the buried history of black classical music—and play some tunes—on a special episode of our podcast, Smarty Pants:

In 1934, Leopold Stokowski and his incomparable Philadelphia Orchestra premiered a new work by a black composer : the Negro Folk Symphony of William Levi Dawson. Four days later, Stokowski conducted the symphony at Carnegie Hall, a performance that was nationally broadcast and widely reviewed. “Hope in the Night,” the second movement, ignited an ovation—the orchestra had to stand. At the close, Dawson was repeatedly called to the stage. Pitts Sanborn of The New York World-Telegram wrote that “the immediate success of the symphony [did not] give rise to doubts as to its enduring qualities. One is eager to hear it again and yet again.” Leonard Liebling of the New York American (like Sanborn, a critic of consequence) went the full distance; he called Dawson’s symphony “the most distinctive and promising American symphonic proclamation which has so far been achieved.” Yet the Negro Folk Symphony would soon be forgotten.

Around the same time, two other notable symphonies by African Americans were prominently premiered: William Grant Still’s Afro-American Symphony, performed by the Rochester Philharmonic in 1931, and Florence Price’s Symphony in E minor, played by the Chicago Symphony in 1933. And yet, writes the music historian Gwynne Kuhner Brown (in her 2012 article “Whatever Happened to William Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony? ”), “the tumultuous approbation [Dawson’s symphony] received from critics and audiences alike set it apart—not only from contemporaneous works by African Americans, but also from most new classical music of the period.”

In 1934, Stokowski told audiences for the Negro Folk Symphony that “a wonderful development is taking place in American music.” In 1963, he returned to the work and recorded it with his American Symphony Orchestra—a reading of seething intensity and irresistible panache. You don’t have to go looking for this recording. It’s hiding in plain sight on YouTube. So is a brilliantly played (if less deeply felt) 1994 Detroit Symphony recording. Nevertheless, the Negro Folk Symphony retains its veil of obscurity. When a rare performance (of the first movement only) was given last February by the orchestra of the State University of New York at Purchase, a prevalent response among the student musicians was shame.

Dawson died at the age of 90 in 1990, an éminence grise. His eminence, however, remained restricted to his choral arrangements of African-American spirituals. Though Pierre Monteux, Otto Klemperer, and Artur Rodziński all expressed interest in conducting the Negro Folk Symphony, though Dawson envisioned it as his Symphony No. 1, he never again composed for orchestra. The reasons are both obvious and not.

Green Book, Peter Farrelly’s Academy Award–winning film about the African-American pianist Don Shirley, tells a pertinent story of an artist in limbo in the 1950s and ’60s. Whatever the veracity of the film’s widely discussed account of a black musician in white America—it succumbs to bloated clichés of race and ethnicity—the real Don Shirley performed Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 with the Boston Pops in 1945 at the age of 18. A couple of decades later, he made unreleased recordings of concertos by Rachmaninoff and Khachaturian. He performed Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue at La Scala, and Gershwin’s Concerto in F at the Metropolitan Opera House for the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. He also composed for orchestra. His admirers included Igor Stravinsky. He did not identify as a jazz artist. But Shirley’s performing career took place in clubs, where he purveyed a singular musical hybrid, intermingling “Blowin’ in the Wind” with a Rachmaninoff etude, or “I Can’t Get Started” with a Chopin nocturne.

Shirley said that, early on, the impresario Sol Hurok advised him that America was not ready for a black pianist playing classical music. Hurok’s word carried authority. He managed the preeminent African-American concert artist of her generation, indeed the most famous African-American woman of her time: Marian Anderson—the exception who proved the rule. And Anderson wasn’t merely an incomparable singer of spirituals. Her wide-ranging recital repertoire included art songs in German and French; Schubert’s “Erlkönig” was one of her specialties.

Anderson’s 1956 autobiography, My Lord, What a Morning, remains a riveting document. She recalls that her first major manager was Arthur Judson, the supreme powerbroker of American classical music. Most of the nation’s important conductors, pianists, and violinists were Judson artists. The unfailing courtesy and formality of her memoir make Anderson’s indictment of Judson all the more chilling. He did not remotely gauge her talent or her potential. She felt her career was at a “standstill.” When Anderson told Judson that she intended to go to Europe, he replied, “If you go … it will only be to satisfy your vanity.” She went anyway.

Anderson discovered far greater success in Europe than in America. It was in Paris, in 1934, that Hurok heard her. She returned to the United States under his management a year later. Notwithstanding her subsequent international acclaim, she did not appear at the Metropolitan Opera until 1955. None of the four individuals most responsible for her famous Met debut, in Verdi’s A Masked Ball, was American born. Hurok was a native of Russia. The Met’s general manager, Rudolf Bing, was born in Vienna. Bing’s musical assistant Max Rudolf (born in Frankfurt) prepared her. Dimitri Mitropoulos (born in Athens) conducted her.

This snapshot limns in microcosm the whiteness of American classical music in the 20th century. Around the same time that Anderson finally sang at the Met, the African-American conductor Dean Dixon discovered himself unemployable in the United States; he wound up with major positions in Gothenburg, Sydney, and Frankfurt. In 1962, the violinist Sanford Allen became the first full-time black member of the New York Philharmonic; he resigned 15 years later, saying that he was “simply tired of being a symbol.” That all this is finally changing augurs well for Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony. In fact, a buried history of symphonic music by black composers is already being vigorously excavated, with Florence Price so far the main beneficiary.

The history in question, remarkably, may be traced to the influence of a famous Bohemian visitor: Antonín Dvořák, who from 1892 to 1895 was the director of New York’s National Conservatory of Music, charged with helping American composers find their own voice. Dvořák was a butcher’s son, schooled in his father’s tavern in Bohemian folk music and dance. A cultural nationalist, he looked for America’s folk music and found it among black Americans. Hearing “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” and “Go Down Moses” for the first time, he experienced a veritable epiphany. In 1893, he told the New York Herald: “I am now satisfied that the future music of this country must be founded upon what are called negro melodies. … In [them] I discover all that is needed for a great and noble school of music.” Dvořák’s prophecy, instantly influential and controversial, correctly anticipated that American music, as known throughout the world, would be black. But the American school he predicted was something different: a canon of symphonies, concertos, and operas infused with the black vernacular, anchoring a New World classical music idiom.

Dvořák’s enthusiasm for appropriated “negro melodies” was equally embraced by W. E. B. Du Bois. Like Dvořák, Du Bois was a devotee of Richard Wagner. As a graduate student in Berlin, he absorbed The Ring of the Nibelung. In the tradition of Wagner, Johann Gottfried von Herder, and other German theorists of race, Du Bois linked collective purpose and moral instruction to “folk” wisdom: the soul of a people. To him it was obvious that America’s sorrow songs—slave songs of the cotton field and campground—constituted a usable past that, subjected to evolutionary development, would yield a desired native concert language. Formal training and performance, for Du Bois, did not impugn the authenticity of folk sources; rather, a reconciliation of authority and cosmopolitan finesse would result. Concomitantly, ragtime, the blues, and jazz threatened Du Bois’s cultural-political agenda. A child of the Gilded Age, born in tolerant Massachusetts in 1868, he endorsed uplift.

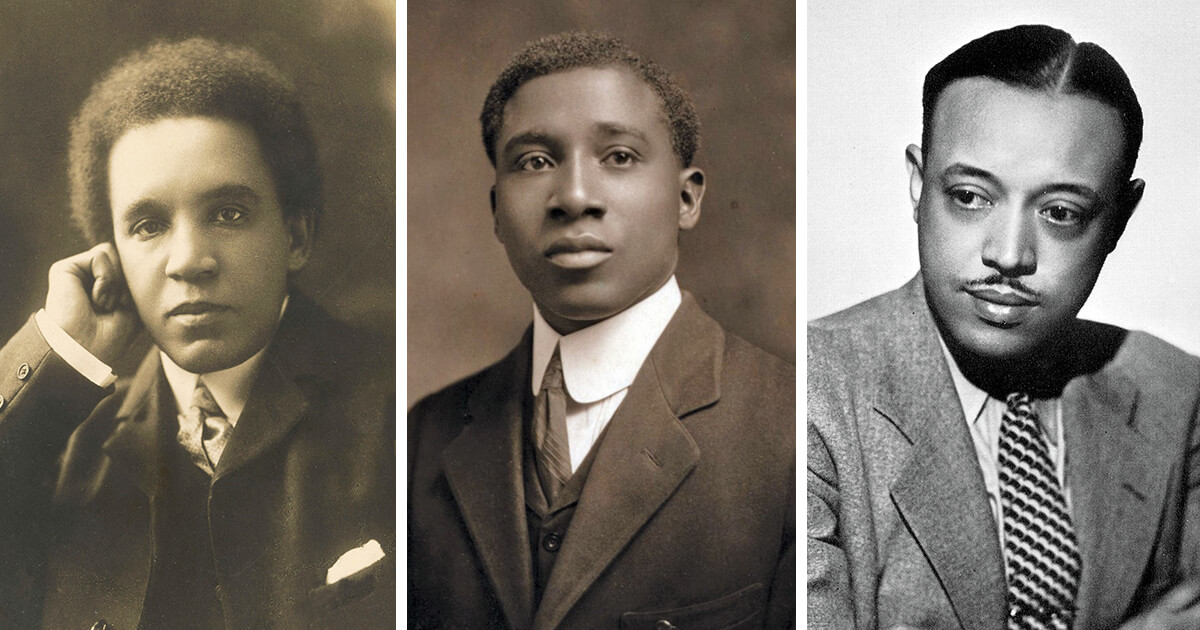

From left to right: the composers Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (an Englishman born to a mixed-race couple), Nathaniel Dett, and William Grant Still (Chronicle/Alamy; Everett Collection/Alamy; Lebrecht Music & Arts/Alamy)

Du Bois focused his hopes on the one extant black concert composer of high consequence: Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, born in London in 1875 to a white British mother and an African father. Coleridge-Taylor in turn found inspiration in Dvořák, whose influence is readily discernible in his 1898 cantata Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast—a sensation on both sides of the Atlantic. Coleridge-Taylor met Du Bois at the First Pan-African Congress in London in 1900. He had previously encountered Paul Laurence Dunbar, whose poems and stories notably mined the black vernacular. They and others pointed Coleridge-Taylor toward African-American roots.

And so in 1905, a year after his first visit to the United States, Coleridge-Taylor published a set of Twenty-Four Negro Melodies for solo piano. The 10th of these was a setting of “Deep River,” the sorrow song he most admired. Coleridge-Taylor’s “Deep River” was taken up by Maud Powell, the leading American concert violinist of the day; she became the first white American to record a black spiritual. His subsequent output increasingly explored the uses of “negro melodies.” But in truth, Coleridge-Taylor did not live up to Du Bois’s high expectations; the decorum of the Victorian parlor is never remote from such pleasant orchestral excursions as The Bamboula and Keep Me from Sinkin’ Down (with solo violin).

Another black American advising Coleridge-Taylor was Harry Burleigh, once Dvořák’s assistant in New York. Burleigh composed his own settings of “Deep River” beginning in 1913—significantly, just after Coleridge-Taylor’s early death. It was with Burleigh’s iconic “Deep River” that the spiritual as concert song was born. It was first sung by such eminent operatic artists as Frances Alda, Frieda Hempel, and Louise Homer, later by Anderson and Paul Robeson. Burleigh himself was a popular concert baritone whose repertoire notably included Mendelssohn’s oratorio Elijah. He additionally composed art songs that avoided the black vernacular; they, too, were widely performed for a time. But Burleigh, Anderson, Robeson, and the tenor Roland Hayes notwithstanding, the American recital stage retained its white complexion. Burleigh’s orbit was further confined because he was not trained to compose for America’s signature classical-music institution: the orchestra.

Those developments set the stage for Nathaniel Dett (1882–1943), a notably original black composer (and poet and essayist) who studied at Oberlin, Columbia, Harvard, and the Eastman School, and in France with Nadia Boulanger. Dett’s one large work with orchestra is an oratorio, The Ordering of Moses (1937). His is the lineage to which Florence Price, William Grant Still, and William Dawson belong—a substratum of American classical music that quietly coexisted with the glamour of Stokowski, Serge Koussevitzky, and Arturo Toscanini; with Jascha Heifetz, Vladimir Horowitz, and Arthur Rubinstein.

An enduring presence throughout this buried narrative is Dvořák, who fostered a coterie of musicians and writers, black and white, dedicated to forging a New World concert idiom imprinted with the sorrow songs. The Boston publisher of Coleridge-Taylor’s Twenty-Four Negro Melodies, William Arms Fisher, had studied with Dvořák in New York. In 1922, Fisher created the famous synthetic spiritual “Goin’ Home,” based on the tune that begins the Largo movement of Dvořák’s New World Symphony. That same Dvořák melody—the most celebrated English horn solo in the repertoire, a faux plantation song cradled by a luxurious chordal accompaniment—had also exerted a decisive influence on Burleigh’s “Deep River.” Both Price and Still studied in Boston with George W. C hadwick—whom Dvořák, in the 1890s, had pointed toward “negro melodies” and a more consciously “American” style.

For Dawson, Dvořák was at all times a lodestar, a source of validation. But despite the efforts of Dvořák, Du Bois, Coleridge-Taylor, Burleigh, and others for whom the sorrow songs suggested limitless potential for the concert hall and the opera house, America’s black musical mother lode predominantly flourished—wondrously—in popular musical realms. American classical music stayed Eurocentric and white. No canonizing “American school” emerged. To this day, New World orchestras mainly play Old World music.

Dett’s The Ordering of Moses was prominently premiered: by the Cincinnati Symphony in 1937 on national radio. Midway through, however, the broadcast was stopped without explanation—presumably because of listener complaints that the composer was black. After that, like Dawson’s symphony, Dett’s cantata disappeared.

Racial prejudice, personal and institutional, obviously inhibited the potential success of a Dett, Dawson, Still, or Price. But a subtler prejudice was aesthetic.

Around the time of the Great War, the literary historian Van Wyck Brooks went in search of a usable past for American writers and—famously—came up empty-handed. In his view, modernist American novelists and poets, for whom originality was a validating priority, would have to begin anew. But not long after, Brooks looked again and discerned forebears. A colleague, F. O. Matthiessen, in 1941 decisively reclaimed Emerson, Whitman, Thoreau, Hawthorne, and Melville as distinctly New World writers comparable to the European masters. Ernest Hemingway declared that “all modern American literature comes from” Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. And William Faulkner called Moby-Dick the one novel he wished he could have written.

In the neighboring realm of American music, there were no historians to undertake a comparable study—the discipline of music history remained nascent in America. And so this task mainly fell to two composers, Aaron Copland and Virgil Thomson. In their widely read books, essays, and reviews, neither was inclined to scrutinize America’s musical past in any detail. Both prematurely declared the music of such 19th-century composers as John Knowles Paine and George Chadwick as “kindergarten” or “adolescent” exercises enslaved to Germanic models. Was Chadwick’s music really “a pale copy of … continental models,” as Thomson asserted? That could never be said of Chadwick’s salty 1897 orchestral cameo Jubilee, with its Winslow Homer high jinks and heady whiff of Stephen Foster. But no matter. For Thomson, come-of-age American music, first materializing around 1910, was lean, precise, and poised, cleansed of prairie dust and of Germanic angst and introspection. A subtext of these up-to-date conclusions was modernist mistrust of the vernacular musical past.

One pre-1910 composer long written off by Copland and Thomson as an inspired dilettante was Charles Ives. Beginning around 1900, Ives sewed into his dense symphonic tapestries all manner of parlor songs and hymns, patriotic songs, minstrel songs, abolitionist songs, and Civil War songs. These were sometimes residual shards and fragments, sometimes whole melodies lustily sung. He relished the pure vernacular so memorably praised by Emerson in his poem “Music”:

’Tis not in the high stars alone,

Nor in the cups of budding flowers,

Nor in the redbreast’s mellow tone,

Nor in the bow that smiles in showers,

But in the mud and scum of things

There alway, alway something sings

Ives pertinently wrote, “To think hard and deeply and to say what is thought regardless of consequences may produce a first impression either of great translucence or of great muddiness—but in the latter there may be hidden possibilities. … Orderly reason does not always have to be a visible part of all great things.”

In a 1950s production of Gershwin’s opera at the Stoll Theatre in London, Urylee Leonardos (Bess) sings to LaVern Hutcherson (Porgy). (Alamy)

Ives reveled in unadulterated “mud.” No less was this the case with George Gershwin, who thought nothing of implanting tunes in popular idioms—southern, Yankee, Cuban—in a concerto or tone poem. Gershwin, too, was mainly disdained by Copland and Thomson. This mattered, and matters still, because Ives and Gershwin, however “unused” by their American contemporaries, may plausibly be regarded as the two great creative talents in the history of American classical music (ask a European). Neither figured on Copland’s various lists of leading American composers. In 1941, by which time Ives’s Concord Sonata—possibly the summit of American keyboard music—had been belatedly premiered to wide notice, Copland wrote that Ives “could not organize his material, particularly in his larger works, so that we come away with a unified impression.” Asked in 1937 how he would compare his own music “to Mr. Gershwin’s jazz,” Copland replied, “Gershwin is serious up to a point. My idea was to intensify it. Not what you get in the dance hall, but to use it cubistically—to make it more exciting than ordinary jazz.” Comparably, Thomson, as late as 1972, positioned Ives as a “homespun Yankee tinkerer” rather than a full professional; his prediction that Edward MacDowell (a paragon American composer a century ago) “may well survive” Ives has proved risible. As for Porgy and Bess, it was Thomson’s 1935 view that Gershwin “does not even know what an opera is.”

If any single piece of music heralded American modernism, it was Copland’s Piano Variations of 1930. A clarion wake-up call for come-of-age compatriots, it declaims a kind of pastlessness. Though its skittish rhythms sublimate jazz, the main affect is one of skyscraper music of steel and concrete, vibrating with the nervous energy of the city. Roots in the soil are eschewed. Afterward, this clean “American” sound acquired a folkloric social conscience spurred by the Depression and World War II. The dissection and recombination of cowboy and dance hall tunes, jostled by complexly shifting meters, became Copland’s solution to what he considered a “formal problem”—that “[m]ost composers have found that there is little that can be done with such material except repeat it.” Copland’s vernacular borrowing in such signature works as El Salón México and Billy the Kid, scrupulously compacted, scrubbed clean of Emersonian mud and scum—not to mention American self-contradiction and racial travail—can seem antiseptic. Compared with Ives or Gershwin, he is ever a synthetic populist.

Dvořák had extolled “negro melodies” and listed 10 adjectives—including “tender,” “passionate,” “solemn,” and “religious”—evoking a protean range of feeling and experience. How much more circumscribed was Copland’s endorsement of jazz half a century later. It had, he wrote in 1941, “only two expressions: the well-known ‘blues’ mood, and the wild, abandoned, almost hysterical and grotesque mood so dear to the youth of all ages. … Any serious composer who attempted to work within those two moods sooner or later became aware of their severe limitations.” Listening to jazz as a stunted art music, Copland was more Eurocentric than such jazz enthusiasts as Béla Bartók, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, Maurice Ravel, Igor Stravinsky, or Kurt Weill—some of whom took to lecturing American composers on the perils of underestimating the pertinence of Harlem. (In the opinion of the late Gunther Schuller, whose musical worlds conjoined “classical” and “jazz,” Milhaud’s La création du monde surpassed all other concert appropriations of jazz. Schuller also greatly admired Frederick Delius’s Appalachia: Variations on an Old Slave Song—a veritable New World symphony inspired by spirituals the British-born composer heard as a young man in rural Florida.)

Around the same time that Copland assessed the limitations of jazz, Thomson endorsed the writings of George Pullen Jackson, who in the 1930s and ’40s influentially maintained that American folk music was fundamentally Anglo and “white.” According to both Jackson and Thomson, black spirituals arose from white spirituals. “The ethnic integrity of American folk music will be surprising news to many who have long held to the melting-pot theory of American life,” Thomson informed readers of the New York Herald-Tribune in 1944, when the collection and study of rural American music—yet another quest for a usable past—marginalized the sorrow songs and jazz as contaminated transformations.

Was Dvořák’s prophecy musically naïve? Not if you agree with the rest of the world that Porgy and Bess is the highest achievement in American classical music. Shostakovich likened Gershwin’s opera—itself a song of sorrow and redemption—to Mussorgsky. Its other transatlantic admirers were as various as Khachaturian, Gian Francesco Malipiero, and Francis Poulenc. But the reigning paradigm for a modernist “American school” had no more use for sorrow songs than for Gershwin or Ives, not to mention the “black” symphonies of Still, Price, or Dawson.

The same fate would have befallen the most popular, most iconic American concert work—Rhapsody in Blue—if Paul Rosenfeld had held sway. Writing in The New Republic, the high priest of American musical modernism detected in Gershwin the Russian Jew a “weakness of spirit, possibly as a consequence of the circumstance that the new world attracted the less stable types.” Rosenfeld vastly preferred the ersatz piano concerto that Copland produced two years after Gershwin’s “hash derivative” Rhapsody. Elevated by Copland, jazz had at last “borne music.”

Copland himself was neither a snob nor a racist. His politics migrated far to the left; he even addressed a 1934 Communist Party picnic in Minnesota. His modernism was genuinely catalytic. His collegial instincts, if sometimes parochial, were generous. But, picnics notwithstanding, he remained an outsider to the quotidian. In New Haven, Ives banged out ragtime at local clubs and hurled his fastball for Yale’s baseball team. Gershwin shouted alongside transported Gullah congregants in a Carolina island church. For all its friendly brio, Copland’s was a whitewashed America.

Today, the high judgments that once diminished Ives and Gershwin are no longer tenable. Modernism has run its course, and the musical schism it once exacerbated—a bifurcation of white and black, “classical” and “popular,” more pronounced here than abroad—has lost its cutting edge. The new opportunities at hand include opportunities for posthumous reclamation—not least for Dawson and his Negro Folk Symphony.

In a 1932 interview, two years before Stokowski premiered his symphony, Dawson said, “I’ve not tried to imitate Beethoven or Brahms, Franck or Ravel—but to be just myself, a Negro. To me, the finest compliment that could be paid my symphony when it has its premiere is that it unmistakably is not the work of a white man. I want the audience to say: ‘Only a Negro could have written that.’ ”

With its biting syncopations, its bluesy harmonies and pentatonic songs, Dawson’s symphony sounds “black.” It also quotes such spirituals as “Oh, My Little Soul Gwine Shine Like a Star” and “Hallelujah, Lord, I Been Down Into the Sea.” Thinking of Brahms or Dvořák, Dawson commented: “But these are folk songs and we have got to know and treat them as folk songs because they contain the best that’s in us. And anywhere in the civilized world, when you say, ‘This is a folk song,’ all the nations prize their folk songs. All the great composers utilize their folk songs, their source of material for development.” And there is something else going on: Dawson’s tunes will not stand still. His symphony’s developmental panache defies any impression of decorum. As symphonies go, its energies are wild and uninhibited. In fact, following a trip to West Africa in 1952–53, Dawson undertook a revision expanding the percussion complement and minimizing prefabricated structure.

The heart of the work is its central slow movement, “Hope in the Night.” Dawson begins with a tune for English horn—a gesture toward Dvořák and his New World Symphony Largo. Dawson called his English horn solo “a melody that describes the characteristics, hopes, and longings of a Folk held in darkness.” Its pizzicato accompaniment is as harsh and parched as Dvořák’s backdrop is beatific: a weary, trudging journey into the light. The journey builds to a clangorous climax, punctuated by gong and chimes: chains of servitude or messengers of fate. The coda is a master inspiration. Here, the three gong strokes that commenced the movement—“the Trinity,” Dawson wrote, “who guides forever the destiny of man”—are amplified by a seismic throb of chimes and timpani. The result is a heaving, pulsating threefold groundswell. This was the tremendous passage that triggered a spontaneous ovation during Stokowski’s 1934 performances.

The entirety of the symphony, Dawson wrote, is unified by a heraldic call “symbolic of the link uniting Africa and her rich heritage with her descendants in America.” The various permutations are subliminal or incantatory, mourning or hortatory. In a program note, Dawson cited a first-movement passage evoking “the rhythmical clapping of the hands and patting of the feet.” The symphony’s distinctive physicality of gesture also produces passages of lightning hand and arm thrusts, and of strutting grandeur. I do not doubt that, 85 years after its premiere, the Negro Folk Symphony retains the power to drive an audience to its feet.

In 1939—five years after Dawson’s symphony—Roy Harris composed his Third Symphony, which Copland and Thomson long considered America’s finest. Harris went on to compose 10 more symphonies. But these works are not heard today. To my ears, the Harris Third sounds pompous and uncertain alongside Dawson’s First. The black symphony of widest exposure remains Still’s Afro-American Symphony of 1931. It is the one anthologized for study in the ubiquitous Norton Anthology of Western Music and the only interwar symphony featured in Columbia Records’s “Black Composer Series” of the mid-1970s. This past February, the Los Angeles Philharmonic reprised “William Grant Still and the Harlem Renaissance.” In 2016, the Cincinnati Symphony revived Nathaniel Dett’s The Ordering of Moses, took it to Carnegie Hall, and recorded it to high acclaim. A decade ago, a trove of Price manuscripts was discovered outside Chicago, including two violin concertos now so widely noticed that a Price revival seems imminent. Two Dawson biographies are underway. The Negro Folk Symphony is surely next in line.

The Harlem Renaissance sage Alain Locke wrote in 1925 that “Negro folk song is not midway its artistic career as yet, and while the preservation of the original folk forms is for the moment the most pressing necessity, an inevitable art development awaits them, as in the past it has awaited all other great folk music.” With its harmonic versatility and polyphonic potential, he wrote, such music could undergo “intricate and original development in directions already the line of advance in modernistic music.” Nine years later, Locke greeted the Negro Folk Symphony as a breakthrough. Of “Hope in the Night,” he wrote that its

greatest grandiloquence is movingly successful. … It is moments like this that I had in mind in writing that the truly Negro music must reflect the folk spirit and eventually epitomize the race experience. To have done this without too much programistic literalness is an achievement and points as significant a path to the Negro musician as was pointed by Dvorak years ago. In fact it is the same path, only much further down the road to native and indigenous musical expression.

Like Du Bois, Locke long championed Roland Hayes, who succeeded Harry Burleigh as the preeminent exponent of the spiritual in concert. Like Du Bois, he mistrusted the popular musical marketplace in favor of elite realms of art. An opposing camp included Harlem’s loudest white cheerleader: Carl Van Vechten, who deplored Hayes’s refinements. This—and Van Vechten’s celebration of the blues and jazz—ignited a furious rebuttal from Du Bois, who discerned in Van Vechten a decadent voyeur in love with black exoticism. But Van Vechten’s revisionism was supported by the black writers Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. Hughes heard in jazz “the eternal tom-tom beating of the Negro soul.” He deplored the “race toward whiteness” in the uses of black music. Hurston similarly deplored a “flight from blackness.” She heard concert spirituals “squeezing all of the rich black juice out of the songs,” a “sort of musical octoroon.” Pitting authenticity against assimilation, the debate identified conflicting vernacular resources, old and new, rural and urban.

Is Porgy and Bess a true fulfillment of Dvořák’s prophecy, vindicating the road not taken? Or does it exemplify an eviscerating “race toward whiteness”? The evidence of its resilience, of its international reputation, of its inspired appropriation by Billie Holiday and Miles Davis all argue in its favor. The impresario David Gockley, whose Houston Grand Opera played a crucial role in implanting Porgy in the mainstream operatic repertoire, once wrote that Gershwin had successfully “fused folk, jazz, and classical elements. … What would have happened if he had lived another thirty years and contributed another eight or ten operas to the repertory? I believe a potential unique vein of American opera has never been allowed to develop and find its voice.”

I would tweak Gockley’s question to focus on the institutional anchor for American classical music: the concert orchestra. Does William Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony signify an ephemeral footnote or a squandered opportunity? In the history of 20th-century American music, “negro melodies” migrated to popular genres with magnificent results—in part through natural affinity, in part because they were otherwise pushed aside. What if Dawson had composed another half-dozen symphonic works? What if he could have realized his aspiration to become a symphonic conductor? Might American classical music have canonized, in parallel with jazz, an “American school” privileging the black vernacular?

We may soon glimpse some answers to these paramount cultural questions.

Listen to Joseph Horowitz and Sudip Bose discuss the buried history of black classical music—and play some tunes—on a special episode of our podcast, Smarty Pants: