Nolan Preece has been experimenting with chemical painting since the 1980s, and continues to work at perfecting the medium. After creating works with an environmental focus, he now depicts the mountains surrounding his home in Reno, Nevada. Here, he discusses the shape of the landscape, why he considers himself a painter, and how the colors of the desert resonate with him.

“I’ve been working with these chemically derived images since 1981. I got my MFA at Utah State University, where they trained us in the Ansel Adams technique. For my thesis, I decided to go rogue. I started trying things like the Sabatier effect, which is solarisation, and then alternative photo processes. About 1981, I started experimenting by painting with chemistry, and mixing it with a printed image. I originally called it a chemogram, but there was another fellow, named Pierre Cordier, who was doing a similar technique—they gave him a big show in the 1950s at MoMA. We hooked up and started to talk, and decided that I should go with his terminology and call what I was doing a chemigram.

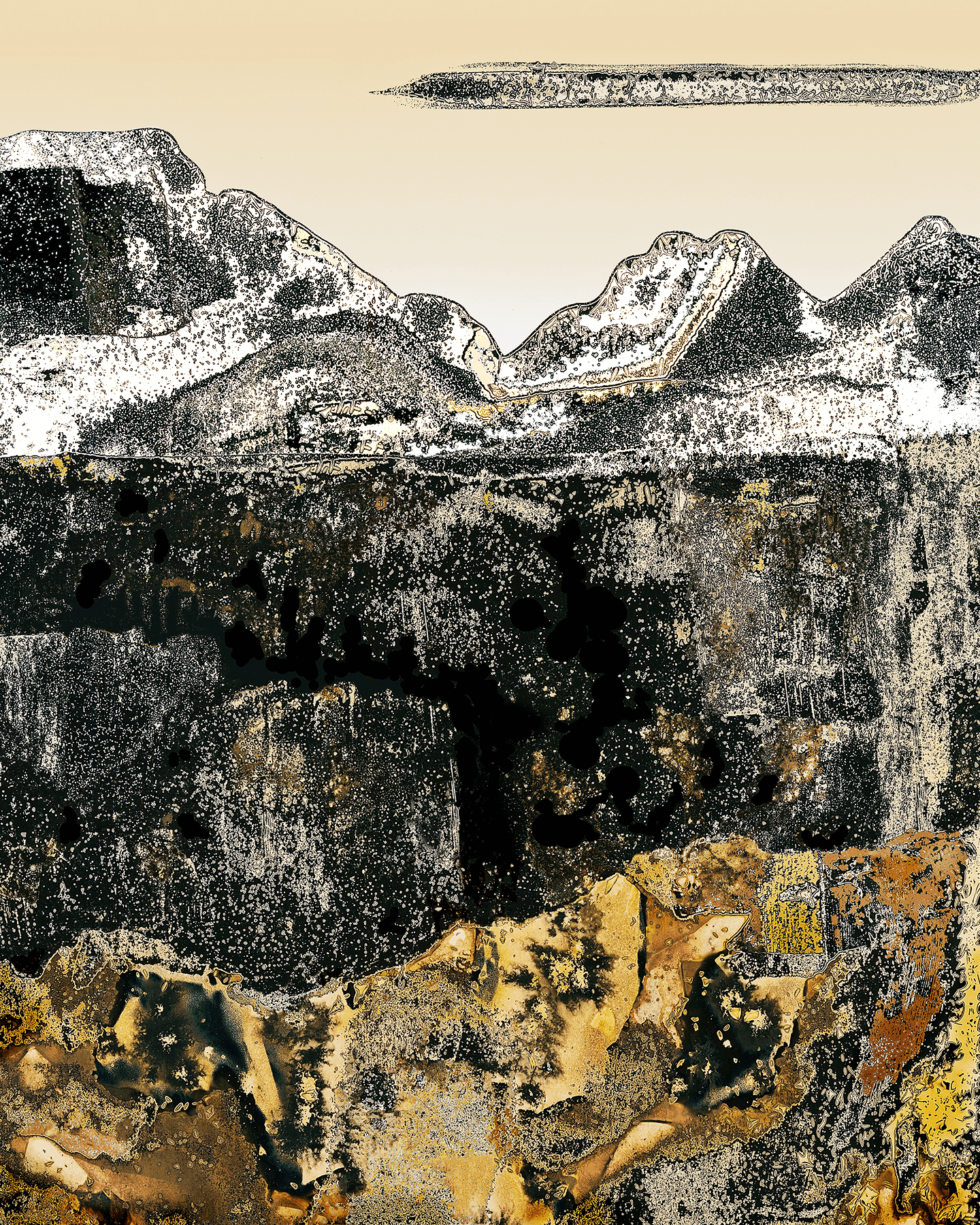

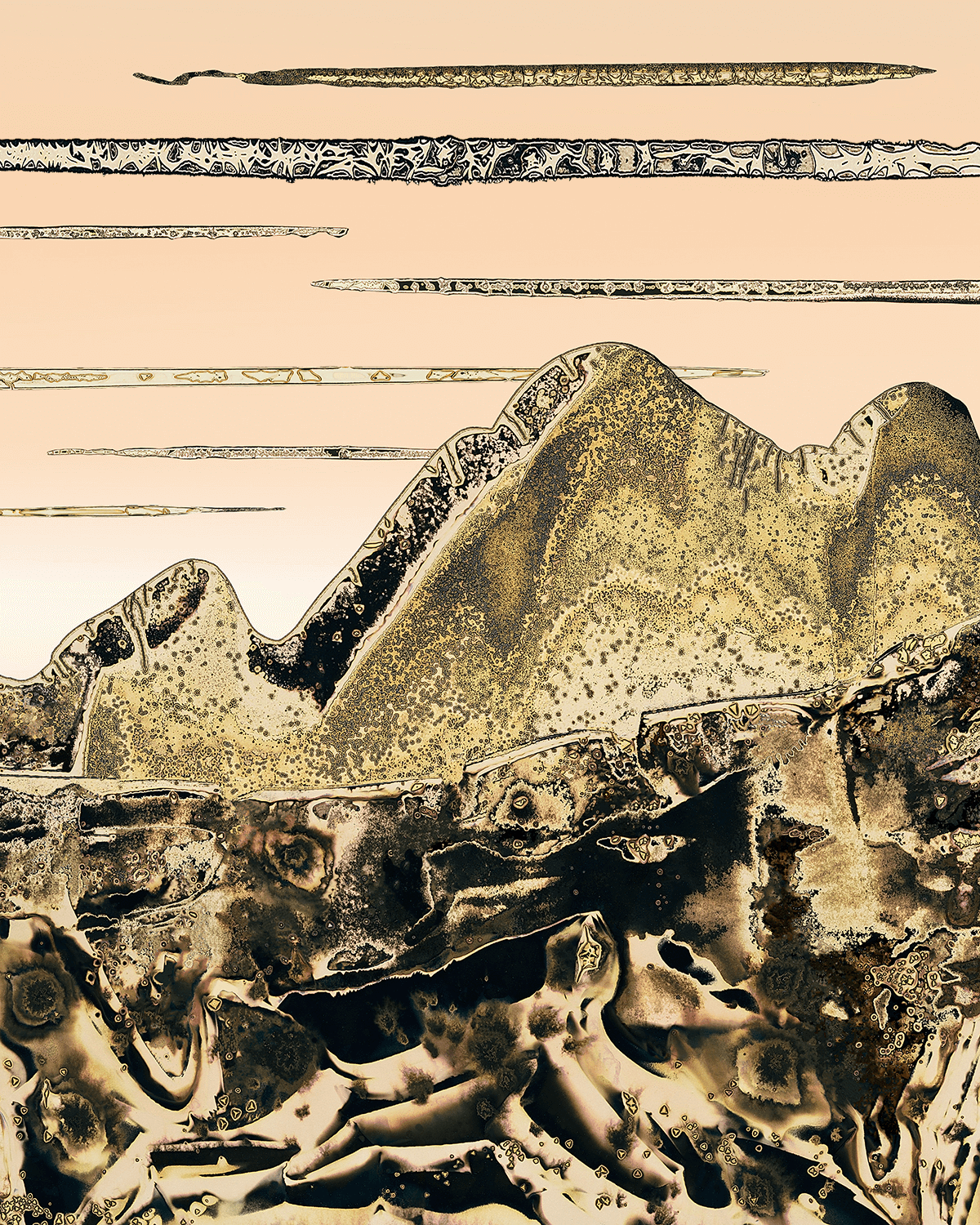

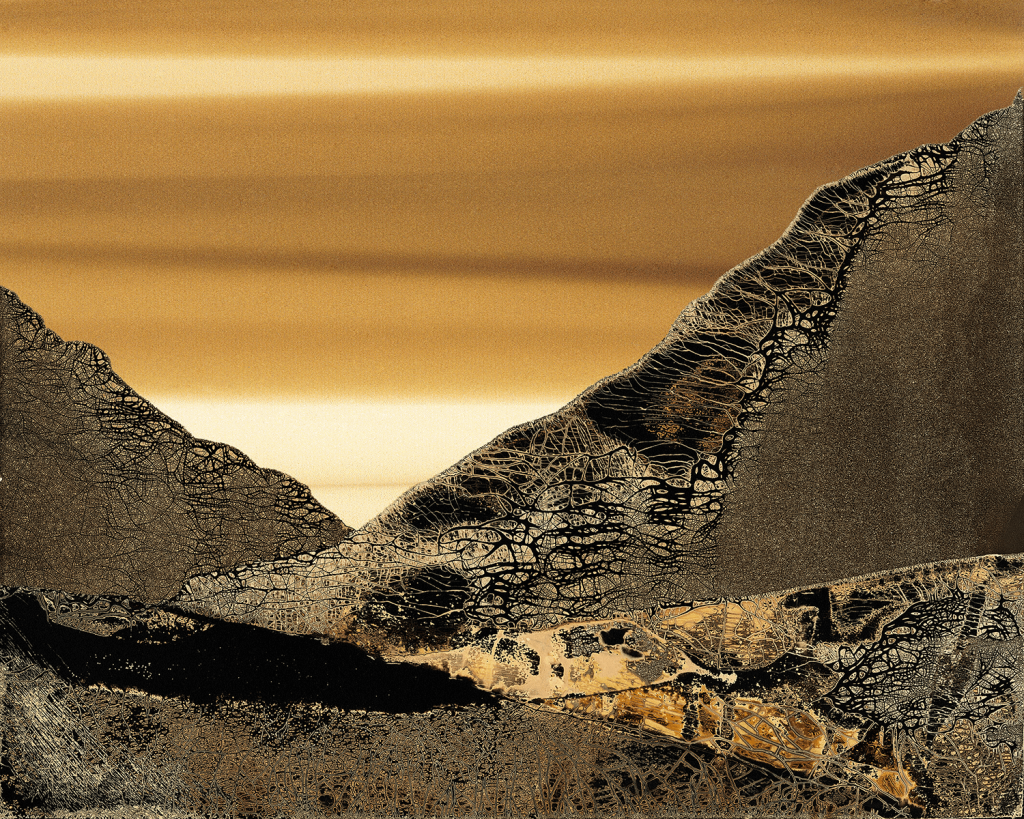

A chemigram is an equal mix of photography, printmaking, and painting. The old photo materials had silver in them, and that’s what does the work for you. I still use developer and fixer as my main chemicals. By mixing the two, you get gradations and some color. The printmaking aspect is the resist you put on the paper. If you use tape or glue or some acrylics—anything that would hold back the chemical reaction on the paper—you get a different kind of image. And I paint with chemistry to create the final product. My father was a photographer, and also the administrator at a hospital. We lived way out in the sticks, and since it was the 1950s, we had a hard time getting Kodak prepackaged chemistry. So my father would ask the drug salesman who came to the hospital to bring along photography chemicals. We’d produce all of our compound developers and fixers from scratch just by weighing the different chemicals and mixing them. I learned that process from my father, and I still mix all my chemicals from scratch today.

I’m one of the few chemigram artists working figuratively—most of them like to work with the abstract quality of the chemigram. When I realized that I could make landscape paintings with the resists and get some unusual figurative results, all of a sudden it became popular. I used to make abstracted eco-art that dealt with issues like climate change, and no one was buying into that. But the second I started making landscapes, they were flying off the shelf. So much of art is grounded in still life and landscape.

I’ve lived in the Great Basin for 40 years—half of that time I was on the Utah side against the Wasatch Range, but now I live on the slopes of the Sierra Nevada. I can look out from my deck and see them right there. The Sierras’ rock formations, which can have gold and iron coloration, are dynamic. One thing about the desert is that since there isn’t much vegetation, the landforms jump out at you. The color of the soil and the mineralization that’s taken place down on the surface. I like the rich browns, reds, and yellow ochres. The desert is attractive to me, because the colors you find in the desert are unlike anything else.”