Child of Light: A Biography of Robert Stone by Madison Smartt Bell; Doubleday, 608 pp., $35

A profile of novelist Robert Stone that appeared in New York magazine in 1997 offered this summary: “It has been Stone’s peculiar fate to have great success without great recognition.” Nearly 60, he had already won the National Book Award, for Dog Soldiers (1974), which was, in addition, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. A Flag for Sunrise (1981)—which was also a finalist for the Pulitzer and the PEN/Faulkner Award—and Outerbridge Reach (1992) had been finalists for the National Book Award. More honors and bestsellers were yet to come before his death in 2015.

However, despite Madison Smartt Bell’s assertion that Stone attained “a secure place in the American literary pantheon,” nowhere is he mentioned in the Columbia Literary History of the United States (1988) or the more recent and unconventional New Literary History of America (2009). Born in 1937, Stone has already faded from cultural conversation in a way that his close contemporaries Don DeLillo (b. 1936), Thomas Pynchon (b. 1937), and Raymond Carver (b. 1938) have not. The Modern Language Association International Bibliography lists 1,039 items on DeLillo, 1,905 on Pynchon, and 413 on Carver but only 53 on Stone. Moreover, since 2010, he has been the subject of only six articles.

Bell, a prolific novelist best known for a trilogy about the Haitian revolution, is determined to propel Stone into the pantheon. He has edited The Eye You See With, a posthumous selection of Stone’s nonfiction, and put together a single volume containing Dog Soldiers, A Flag for Sunrise, and Outerbridge Reach for the canonical Library of America, a publisher with the prestige to confirm an author as a peer of Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Mark Twain. Though he does not stint on Stone’s self-destructive tendencies, Bell’s biography of Stone, Child of Light, is an act of character resuscitation. “He was the writer I wished I could become,” Bell writes. “We were close friends.” Some of the strongest writing in the book recounts Bell’s two perilous trips to Haiti with the often-stewed Stone.

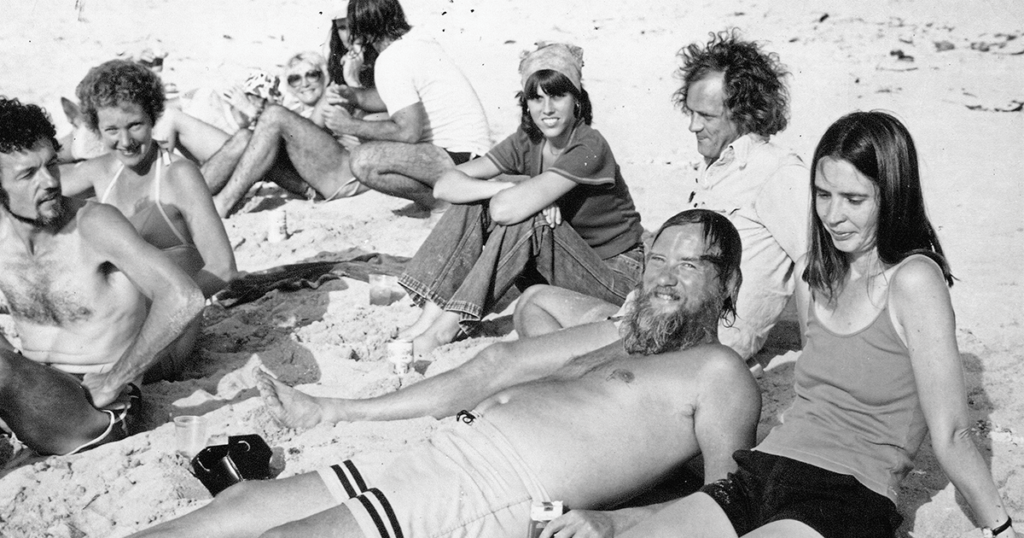

Raised in New York by a schizophrenic mother who moved them through a series of Salvation Army shelters and welfare hotels, Stone never knew who his father was. Four years in a grim Catholic orphanage left him a skeptic who hungered for faith. A tour in the Navy showed him the wider world, and a Stegner Fellowship at Stanford launched him on his writing career. It also introduced him to Ken Kesey and other psychedelic pranksters and immersed him in the 1960s counterculture. Throughout his life, drugs and alcohol would undermine his artistic discipline.

According to Kesey, Stone saw “sinister forces behind every Oreo cookie.” Like Ron Strickland, the cynical documentary filmmaker in Outerbridge Reach—and like Hawthorne, Melville, and Twain—Stone seemed to think it “was his job to look clearly into the dark.” His bleak vision is embodied in the paranoid structure of his fictions, typically a system of calamitous convergence in which unrelated characters eventually collide. Stone’s eye for evil fixes its gaze on New Orleans, Vietnam, Central America, Israel, Haiti, Hollywood, the high seas, and the centers of American power.

The United States has become more fractured and its writers more diffident, but Stone was one of the last American novelists with the ambition and arrogance to confront the enormity of his troubled country. Of virtually all his work, he could say, as he did about his first novel, A Hall of Mirrors (1967): “I had taken America as my subject, and all my quarrels with America went into it.” Those quarrels were fierce, exacerbated by disillusionment. Recounting his own visit to wartime Vietnam, Stone characterized himself as a “thoughtful tourist trying to draw a moral. But there isn’t any moral, it makes no sense at all.” He shared with John Converse, his alter ego in Dog Soldiers, the sense that “I don’t know what I’m doing or why I do it or what it’s like. … Nobody knows.”

Bell finds in Stone’s lapsed Catholicism the key to a sensibility that led him away from dogma but toward fundamental cosmic mysteries. “I felt at various times that I was taking seriously questions that for most educated people were no longer serious questions,” Stone told an interviewer in 1986, “and I ascribed that to my Catholic background. I mean specifically the question of whether or not there is a God or whether or not you can talk about life and its most important elements in religious terms.”

Though Stone lived to 77, much of the latter half of Bell’s biography is a litany of boozy binges, drug overdoses, and stints at rehab facilities as well as physical woes including sciatica, gout, diverticulitis, and emphysema. He broke his elbow at least four times. Yet, until almost the end, he maintained a vigorous schedule of book tours and expeditions to remote and dangerous places. Stone simultaneously juggled as many as four scattered residences on a budget that was sometimes precarious, forcing him into a succession of teaching jobs. An autodidact, his only degree was an honorary one bestowed by Amherst College.

Through it all, Stone’s wife, Janice, Bell’s indispensable informant, was the novelist’s secretary, editor, house manager, and inspiration. She called herself the “handmaid to genius,” though the genius dallied with other women and even fathered a daughter with one. A serious infatuation—with someone Bell coyly calls “Melisandra,” while offering enough clues to suggest her true identity—did not quite wreck a marriage that lasted 55 years.

Stone’s dramas of moral choice under extreme duress have not yet passed their pull date. But what Bell credits as his “unusual instinct for tracking the zeitgeist” might bar Stone’s entrance into the pantheon, as times cease to favor truculent white male titans. Although, echoing Stone’s 1986 Children of Light, Bell calls his biography Child of Light, its subject was spawned in shadows. He makes Stone’s darkness visible.