Notes From the Front

Henry Kissinger’s Vietnam diary shows that he knew the war was lost a decade before it ended

On October 27, 1965, having evaded enemy fire by corkscrewing through a steep descent to a mountain airfield, a Beechcraft 18 opened its door onto a blast of tropical heat. Henry Kissinger had flown through a monsoon from the Vietnam coast to the city of Pleiku on the country’s western border with Cambodia. Home to two of Vietnam’s more than 50 indigenous groups, the Bahnar and Jarai (collectively known as Montagnards), this district capital in the Central Highlands had grown from a colonial hamlet into a city bloated with CIA contractors, U.S. Army Special Forces, a South Vietnamese Army division, and several thousand of the three million refugees who had been driven from their homes during the Second Indochina War—known in Vietnam as the American War and in the United States as the Vietnam War—then entering its 11th year. A new phase in the war had begun in March, when 3,500 Marines splashed ashore. Soon there would be half a million American troops, supported by long-range bombers that would drop on Vietnam more than twice the total tonnage dropped by Allied powers in the European theater during World War II. France had already lost the First Indochina War, after a calamitous defeat at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. The question was whether the United States, with its massive arsenal and legions of troops, might fare better. Kissinger had come to Vietnam in search of the answer.

“The flight to Pleiku was as beautiful as is possible,” Kissinger wrote. Turning inland from the coast, the Beechcraft had navigated between 10,000-foot, cloud-shrouded peaks. On another flight, Kissinger had spied troops fighting on the ground below. “It was an eerie feeling,” he wrote, “to see an action in which thousands of lives are involved and have it appear almost as in a television serial of Indians besieging a Western fort.” Kissinger’s destination was less picturesque. From the air, it looked to him like the set for a Hollywood cowboy movie, “like one of those frontier towns inside a stockade.” The buildings were “heavily sandbagged” with “a mortar shelter in the center of the compound” and a barbed-wire fence around the perimeter. The Pleiku airport was buzzing with fighter jets returning from the first big battle of America’s ground war in Vietnam. Twenty miles to the south, in the village of Plei Me, Montagnard irregulars, led by American special forces advisers, had repulsed an attack by mainline troops from the North Vietnamese Army (NVA), eventually driving them across the border into Cambodia. This was a trial run for the NVA. Could they fight American troops defended by helicopter gunships, bombers, and long-range artillery? The battle convinced Ho Chi Minh, leader of the communist North, that they could. The United States ruled the air, but the communists could assert some measure of control on the ground—enough at least to inflict heavy casualties before retreating to the safety of their bases in Cambodia and Laos. A month later, for example,

17 miles south of Plei Me in the Ia Drang Valley, the communists would kill more than 500 American soldiers before again retreating across the border.

These details about Kissinger’s travels come from a “personal and confidential” diary that he kept during two trips to Vietnam—three weeks in the autumn of 1965 and a few days in the summer of 1966. Access to the diary, which is stored with Kissinger’s papers at the Yale University Library, is granted by permission only. A couple of scholars have drawn on the diary, and Niall Ferguson devotes a chapter to it in his official biography. Although Kissinger described his diary as a collection of “unedited notes written down at the end of each day,” nothing prepared me for the brutal honesty of those notes. Kissinger castigates lying officials, bumbling diplomats, incompetent soldiers. He knows that defending a former French colony–turned–client state, in the absence of a negotiated end to the war, will be an endless suck of treasure and lives. He will spend the next decade trying to spin this lost cause into a simulacrum of victory. Here, on his first days in Vietnam, we see the origins of the tragedy that will dog Kissinger for the rest of his life—up to the 100th birthday he celebrated in 2023. Are we reading the notes of a great diplomat or a war criminal?

Then a professor of government at Harvard, Kissinger was studying the war at the request of the U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. This was his first big governmental assignment, the lucky break that would lead him to the White House, three years later, as President Nixon’s national security adviser. There, Kissinger would eventually oversee the war’s inglorious end in 1975. That first night in Pleiku, 10 years earlier, was the closest he would come to studying the war on the ground. What he saw he chose to ignore, out of either hubris or a mistaken faith in American force. Either way, the experience anticipated the next half century of U.S.-led colonial wars, in Iraq and elsewhere throughout North Africa and the Middle East. If only Kissinger had trusted his own eyes.

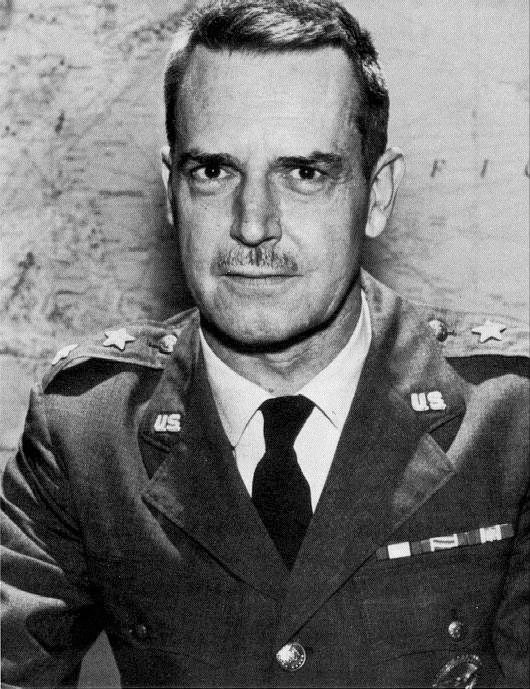

Maxwell Taylor, Henry Cabot Lodge, and Robert McNamara at the Pentagon, June 1964 (Wikimedia Commons)

Kissinger’s diary begins on September 13, 1965, with official briefings in Washington. Having taken a year off from Harvard to prepare for his initial trip to Vietnam, Kissinger visited the directors or deputy directors of all the major agencies involved in the war, from the White House and CIA to the State Department and the Pentagon. Kissinger was on a first-name basis with many of these presidential advisers, particularly those connected to Harvard or invited over the years to speak at his seminars on Divinity Avenue. There was Mac Bundy, former dean at Harvard, now serving as President Johnson’s national security adviser, and his older brother Bill, a former CIA man who was running Far Eastern affairs at the State Department. Bill was “as dapper and smooth and elegant as always.” General Maxwell Taylor, a previous U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam, was as “dapper and shrewd as always.” CIA chief William Colby was just plain “psychotic.” In one office after another, Kissinger was slipped the secret “for eyes only” documents that were being used to run the war. These documents surprised Kissinger with their assessments of how badly the war was going, but so too did the fact that they were being so closely guarded.

The opinions he heard in person, meanwhile, ranged widely. The CIA said it could finish the job with 50,000 more irregular troops on the ground. Dean Rusk at the State Department said victory was just around the corner. The most sobering analysis came from the Pentagon, where Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, according to Kissinger, “wanted to take over the whole country.” In the opposing camp was McNamara’s right-hand man, John McNaughton, who foresaw the war already lost and America’s allies betrayed in a hasty retreat.

It was now Kissinger’s task to see the war for himself.

“I had no idea what the United States can do in the way of projecting its military power abroad until I had seen Vietnam,” he wrote later. “When one flies over Vietnam the sky is covered with airplanes, helicopters. In any area where there are Americans the amount of equipment is breathtaking.” Yet, in spite of its military superiority, the United States controlled no more than 20 percent of the territory in South Vietnam, and many experts put the number closer to zero. Facts were hard to discern, especially given the military’s efforts to obfuscate them. After Kissinger’s plane touched down in Pleiku, two CIA escorts immediately hustled him to a military briefing for what Kissinger called “eyewash”—a barrage of statistics on kill ratios and firepower meant to conceal the reality on the ground. Army experts, he noted, were adept at “giving briefings whose major interest is to overpower you with floods of meaningless statistics and to either kid themselves or deliberately kid you.”

Afterward, Kissinger turned to his CIA escorts for a more honest account. The communists had secretly infiltrated 10 regiments across the Cambodian border and laid siege to the U.S. Special Forces camp at Plei Me, retreating only after 700 American bombing runs had left the mountains around Plei Me pockmarked with craters. This was the first major confrontation between regular troops from the NVA and South Vietnamese forces. When Kissinger asked his “now standard question about the quality of personnel,” the CIA men told him that 10 percent of the district chiefs were “outstanding,” eight percent were “bandits,” and the rest were an unknown amalgam of devious Montagnards and Viets “barely getting by.” Kissinger raised the possibility of a negotiated settlement with the communist North, but the men only scoffed. “The VC [Vietnamese Communists] ,” they told him, “were moving whole divisions through our area without our knowing it until months later.” With no way to monitor a ceasefire, the war would have to be fought to the end. The CIA men guessed it would take 10 years to “finish the job.” They were right, but it was the communists who would do it.

Kissinger at the end of his second visit to Vietnam, bidding farewell to Premier Nguyen Cao Ky in Saigon, July 28, 1966 (Associated Press)

That night, Kissinger slept in a room being used as the command post for the Army’s First Cavalry Division. The chatter of incoming radio calls filled the air as he recorded in his diary what he had learned of the recent battle. NVA regulars had staged a weeklong frontal assault on the camp at Plei Me, which was defended by some 400 irregular soldiers, in addition to a few U.S. and South Vietnamese military advisers. As at other fortifications along the Cambodian border, these men were primarily ethnic Jarai. Kissinger described how the battle at Plei Me had been preceded by a trial run:

Two months ago, the VC attacked an American special forces camp at Duc Co, about fifty miles from Pleiku on the Cambodian border. Duc Co like all special forces camps was manned by a battalion of 650 men with fourteen American advisors. The VC attacked in regimental strength. One battalion assaulted the camp and the other two battalions set an ambush for any relief force that might be sent. The relief force was, in fact, sent and ambushed and suffered heavy losses. … The attack on Duc Co was a training mission for a new regiment. … It had never been designed to take the camp. … The real purpose was to ambush relief forces. The VC had obviously studied Duc Co operations very well in preparing for the Pleime battle. This time they moved six battalions into action, five combat battalions and one battalion of porters.

This would be the communist strategy throughout the war. Attack a fortified camp with troops sufficient to overrun it, but retreat—or appear to retreat—as reinforcements arrived. Ambush the reinforcements, inflict as many casualties as possible, and again retreat in the face of American airstrikes and artillery. The communists would clear the battlefield of dead and wounded and cross the border into sanctuaries beyond the lawful reach of American bombers. It was as if the two sides were fighting different wars. The Vietnamese engineered attacks and ambushes. The Americans repulsed the attacks and declared victory whenever they retook contested territory.

Earlier in the evening, Kissinger had dined with two generals and two colonels, both of them recently returned from the battle at Plei Me. When he asked the colonels about the “political situation,” they told him that earlier in the year, the communists had “concentrated and knocked off all the sea coast between Danang and Nha Trang including a strategic valley in [which] much of the rice harvests of Vin Din province is grown. This valley is still under VC control as is most of the coast.”

The situation was no better up in the mountains. There, 20 fortified camps were under siege. No longer engaged in controlling the population through “pacification,” the camps had become sitting targets. Even the figures on pacification were misleading, said the colonels. One province was pacified “because the VC had put no effort into it.” Another was pacified “because it was being used as a rest and recuperation area by both sides.” As for the quality of the local district chiefs, Kissinger learned that “three were outstanding, five were barely getting by, three were not worth the powder to blow them up and one had recently been killed.”

Furthermore, Kissinger learned that “not a single operation of larger than battalion size conducted with Vietnamese troops had ever been successful because the security had always been compromised. They had captured Viet Cong documents which contained details of information about operational plans that had to come directly from the highest headquarters.” As we learned after the war, some of these documents were obtained by Pham Xuan An, the well-placed journalist in Saigon who worked simultaneously for Time magazine and Ho Chi Minh. But the communists had spies everywhere, tipping them off to troop movements and attacks throughout the country.

“I sat around with a group of officers and with the chief of special operations of the CIA just talking about things in general,” Kissinger wrote, describing his sleepless night in Pleiku. “The morale of these people was a curious mixture of dedication to their job and exasperation with the problems they were facing here. The CIA men told about what happened when the so-called hop tac areas were established.” Hop tac were the “oil spots,” the pacified parts of a district, which were supposed to expand outward and eventually cover the entire area as administrative control spread from village to village. Unfortunately, the communists excelled at working the oil spot strategy in reverse. They infiltrated agents into pacified villages and linked them together into safe havens for the movement of troops and materiel. The CIA men told of incidents where “known VC agents” had been arrested but released because of “Buddhist riots on the street” or someone having “got on the telephone and called the Prime Minister,” Kissinger wrote. “Several others present,” apart from the CIA men, “had horror stories to tell of inefficiency, corruption, and utter confusion. The consensus seemed to be that the primary hope was that the other side was equally as confused.”

The following day, after breakfast, two CIA men took Kissinger to visit a Montagnard village, which was doubling as a special forces training center. There, colorfully costumed villagers were being drilled by Army Green Berets, who specialized in operating behind enemy lines. The Montagnards looked competent, but it was “hard to tell how much of it was eyewash and how much of it was real,” Kissinger noted. “In every classroom I visited, for example, people were working with a frenzy and a dedication which I have not found to be general in Vietnam, but perhaps I am getting as suspicious as everybody else.” Still, Kissinger was charmed by the tribal village. “The Montagnards live in a different fashion from the Vietnamese,” he wrote.

Their houses are built on stilts and whole family groups live in one long house which may house as many as fifty people in separate compartments. One side of the house is a kind of veranda on which they grind rice and dry tobacco leaves. Underneath the house there are pigs and other livestock. In the middle of the village there is a house with a very high gable also on stilts somewhat like an Alpine chalet which is called the happy house where all [the] bachelors of the village live until they are married.

Next to the happy house was a gift from the United States: a “very impressive concrete installation which was intended to be a market. In fact, it is the most impressive building in the village, if not in Pleiku. It now stands utterly deserted because Montagnards never trade with each other,” Kissinger wrote.

After visiting with the Montagnards, Kissinger went to meet General Vin Loc, commander of the South Vietnamese forces in the area, a man “almost universally despised by the American advisers as [a] dilettante, playful and erratic, and extremely emotional.” While bragging about his accomplishments, the general “spoke of the battle of Plei Me entirely as if it had been a victory brought about by his superior generalship.” In fact, General Loc had lost 50 hamlets in the previous three months, and his region was essentially a no man’s land controlled by the communists.

Rushed to yet another meeting, Kissinger “received the usual eyewash briefing about the splendid accomplishments of the special forces teams which gave the impression that the war was being won.” The major giving the briefing eventually confessed that his troops were suffering from “ ‘campitis’; that is, staying in their camp and praying that they would not be attacked.”

Later that afternoon, Kissinger flew to the border to visit the special forces camp at Dak To. This would be his deepest foray into the Vietnamese countryside. In a mountain valley on the Laotian border, surrounded by 4,000-foot peaks covered in triple canopy forest, Dak To—much like Dien Bien Phu during the First Indochina War—was a sitting duck for the communists. This “is the northern-most outpost in Kontum Province, fifteen miles from the Laotian border on the main infiltration route of the Viet Cong,” Kissinger noted.

It contains a special forces camp and a regimental headquarters of the Vietnamese Army. Dak To had been overrun by the VC in June and recaptured only in August. It can be reached only by air since all the roads to it are closed. When we arrived we found one of the L19 spotter planes circling the airfield to look for possible VC snipers. The airfield is right next to the special forces camp, which contains 14 Americans, at the moment 50 Seabees [military construction workers], and 650 Montagnards. The Seabees are there in order to dig underground installations, since all units will have to be sheltered underground, the post being constantly exposed to VC attack.

The Americans there were an extremely impressive group, and as soon as one gets away from the really almost compulsive lying of the headquarters, one has to be moved by the dedication of these people—stuck out in an area as bait where they can be attacked at any moment by VC units of any size and who are almost certainly doomed if the VC ever consider it worth their while to take the camp. The Montagnards are living in little huts beside the American shelters, each Montagnard having an underground shelter near his hut in which he lives with his wife. The Montagnards will not fight unless their families are with them. Another attribute of the Montagnards is that they are absolutely loyal for their term in service. They fight strictly as mercenaries, and then at some point they will simply put down their arms and leave.

The captain who commanded the camp gave Kissinger a quick tour. Then they drove two miles down the road to the regimental headquarters. “The nature of the situation,” Kissinger wrote,

is shown by the fact that for this distance, even though there are 650 troops in the special forces camp and 2,000 at regimental headquarters, the road between the special forces camp and the Vietnamese regimental headquarters is impassable at night as it is always infested by VC guerrillas. Also, no planes can land at the airfield after 4 o’clock since the VC might shoot the plane down at dusk. The reason they are reluctant to shoot planes down in the daytime is not because they are unable to do it, but because they would give away their position and be subjected to aerial bombardment.

Kissinger met in rapid succession with the provincial chief, district chief, and regimental commander, who told him that 80 percent of Kontum province was under government control. In fact, almost none of the province was under government control, and the communists had overrun more than 100 hamlets in the past eight months. After lunch in “the very primitive regimental mess,” Kissinger took aside Major Tyler, the provincial adviser for Kontum province; Major Allen, the regimental adviser; and Captain Ruehlin, commander of the Dak To camp. “I asked them to tell me frankly how they rated the ability of the Vietnamese with whom they were dealing,” he wrote. They replied:

The province chief was incapable; he did not react quickly, he did not do the job; he was unwilling to delegate responsibility—in fact there was a remarkable lack of interest on his part in prosecuting the war. I then asked about the district chiefs. Major Tyler said there had been five districts in Kontum province; two had been lost, one had been combined with another. Of the two districts that were left, the district chiefs were venal, cowardly, incompetent and almost every other bad adjective they could apply to them.

Major Tyler and Major Allen, neither one of whom seemed hysterical, said that they had the distinct impression that the Vietnamese had no interest in catching the VC. There was a tendency on the part of all Vietnamese units to avoid casualties. There was a stigma to losing troops. Major Tyler told me that he knew of many operations that had been conducted by the provincial chief with his regional forces south of Kontum when all the intelligence reports said that the VC were north of Kontum. I asked Major Tyler and Major Allen what percentage of contacts had been initiated by the Vietnamese. Major Tyler said that in his three months on the job not a single contact with the VC had been initiated by the Vietnamese units. All contacts had been initiated by the VC. Major Tyler added that all the operations conducted with Vietnamese units were penetrated; for example, he had run two road-clearing operations between Dak To and Kontum with two battalions each. Before each of these road-clearing operations two bridges were blown. No bridge had ever been blown as long as the VC [were] controlling the road and collecting taxes.

Again, Kissinger speculated about negotiating a ceasefire, wondering whether the VC might stop their infiltrations in return for certain concessions, such as a halt to American bombing in the North. “All the Americans agreed that monitoring VC infiltration through Kontum province was absolutely impossible,” he wrote. “They pointed out that the elephant grass was twelve feet high and unless one physically stumbled on a man it was impossible to see him even from an airplane.”

Kissinger asked to visit another Montagnard village. A convoy of soldiers sent from regimental headquarters accompanied him 10 kilometers into the mountains. As he later wrote in his diary:

We formed a convoy with two weapons carriers, one in front and one in the rear and an American L19 flying low overhead and along the side of the road. I am sure that the greatest danger to which we were exposed was the fantastic speed with which we went over a dirt road which was absolutely full of holes. We never went below 50 miles [per hour]. … On both sides of the road elephant grass grew higher than the jeep. If a VC patrol had by accident been there and had decided to take us out it could have fired on us and gotten away before anybody could possibly have reacted. … I was met by the village chief who gave me a bracelet, which is the Montagnard sign of friendship, and a model of a “happy house.” We then raced back to the airfield, because it was getting late in the day and we had to get off before dusk.

This model happy house was Kissinger’s prized souvenir from his travels in Vietnam. When it arrived back in Cambridge smashed to pieces, Kissinger asked an official at the U.S. Embassy to help him obtain another one.

From Dak To, Kissinger embarked on “a harrowing flight back to Saigon” through late-day thunderstorms. Thanks to the “grand-daddy” of all traffic jams, it took Kissinger two hours to get from the airport to the embassy residence, where he was staying, and he spent the time listening to “harrowing tales of inefficiency, confusion, and general bungling” from the CIA man chauffeuring him. Later that evening, a dinner was held in Kissinger’s honor, but as he recorded, “I was so exhausted that I don’t really remember very well what was said, except that the labor attaché too complained about corruption and inefficiency and the inability of the government to get any popular base.”

So ended his first two days in country.

Some of Kissinger’s most trenchant remarks were reserved for his host, U.S. Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge Jr.: “I must say that I never had much use for Lodge in the United States thinking him insufferably arrogant and not very bright.” Kissinger met with Lodge every morning over breakfast and sometimes again in the evening for cocktails or dinner. He informed the ambassador about his meetings with various officials who were struggling to run a government that kept collapsing every 15 weeks. This was Lodge’s second tour of duty in Vietnam. The former senator from Massachusetts, who had lost his seat to the young John F. Kennedy, was later appointed by President Kennedy to serve as ambassador to Vietnam in 1963 and ’64. After a failed bid for the presidency, Lodge was reappointed by Lyndon Johnson in 1965. Lodge was the Republican beard for two Democratic presidents, neither of whom wanted to be accused of “losing” Vietnam as their predecessors had “lost” China. On his first tour of duty, Lodge greenlighted the assassination of Ngo Dinh Diem, the Vietnamese president who had fallen out of favor with his American backers. On his second tour of duty, Lodge was overseeing the arrival of U.S. combat troops in Vietnam.

One morning at breakfast, Kissinger found Lodge upset and distraught. Lodge had learned that an oral history of the Kennedy administration was being compiled by the former president’s advisers. They were fingering Lodge as the trigger man for Diem’s assassination, supposedly done without Kennedy’s knowledge or approval. Lodge gave Kissinger the cable traffic to review, hoping he could set the record straight on his return to Washington. “I had no choice,” Lodge told Kissinger. Diem’s brother, Nhu, who ran the secret police and Vietnam’s drug syndicates, had been the brains of the operation. He had provoked Buddhist riots, which included scenes of monks setting themselves aflame in the streets of Saigon. Nhu refused to go into exile. “He was a drug addict,” Lodge said. “Nhu had lost his mind. He was taking an enormous amount of opium. If Diem had let Nhu go both of them would still be alive today.” By this point, Kissinger had developed a slightly higher opinion of his host. “He is gruff and he does not have the highest IQ,” Kissinger wrote, but the ambassador was also “admirable,” honorable, and straightforward. The two men shared a low opinion of Defense Secretary Robert McNamara. He is “a very odd man,” Lodge said. To save time, McNamara wrote his reports on Vietnam before visiting the country. Kissinger, when he was briefed at the Pentagon, had been advised to do the same thing.

Hoping to negotiate a ceasefire, Kissinger asked Lodge for the names of South Vietnam’s communist leaders. Lodge said he had no idea who they were. Kissinger was dumbfounded when he got the same answer from the CIA station chief and other American officials. Lodge confided to Kissinger that he did have one possible lead. A young Vietnamese woman, whom he had met at an embassy function, had told him that he was being targeted for assassination. Suspecting she might have contacts among the communists, Lodge wanted to arrange a private dinner with her. Kissinger, who enjoyed the company of beautiful women and found Vietnamese women among the most beautiful in the world, advised Lodge against this plan. It could be a honey trap, he said, with the woman herself being the assassin.

Edward Lansdale, 1963 (Wikimedia Commons)

Apart from the ambassador and his staff, the person with whom Kissinger spent the most time was Edward Lansdale, a CIA officer who was running something called the Special Liaison Group. Sometimes at the beginning of the day, sometimes at the end, Kissinger would be driven to Lansdale’s Saigon villa to confirm a rumor or speculate on strategy. On his first night in Vietnam, Kissinger went to see Lansdale, who “invented” the postwar government in the Philippines by suppressing a communist rebellion in the 1950s and then “helped to establish Diem in power against heavy odds.” Lansdale was now out of favor “due to policy disagreements with McNamara.” The Pentagon chief wanted the Army to take over Vietnam and get things straightened out, whereas Lansdale was a proponent of “anti-guerilla warfare” and pacifying the countryside.

When Lodge asked Kissinger what he “thought of the Lansdale group, which is under vicious attack” from everyone else in town, Kissinger somersaulted from pretending ignorance to asserting his opinion. “I could not judge the work they were actually doing,” he said, but any man who could assemble such a crew of “disparate characters” who would “drop everything” to work with him must have “more than ordinary qualities.” The word disparate appears again when Kissinger wrote that “Lansdale’s group is really a knighthood of disparate situations. They are useless in normal times, but in difficult periods it is their dedication on which success may depend.” Kissinger then agreed with Lodge when he proclaimed, “In order to do unusual things you need unusual people and unusual people were difficult.”

Lansdale, “who had always struck me as a little muddle-headed and disorganized in Washington,” Kissinger wrote,

has a curious way with these Asians. He looks at them with his big eyes, he is enormously gentle and patient, and gradually they blossom under his tutelage. Whether this will lead to results is anybody’s guess—since it is not clear to me if anything can lead to results in this country—but I am convinced that if results are possible, they are more likely to come through the Lansdale method than through the desk pounding American method.

In 1961, President Kennedy had tapped Lansdale to run Operation Mongoose, which included several failed attempts to assassinate Fidel Castro. As a result, Lansdale’s career was in the doldrums. In 1965, Lodge invited him back to Vietnam, where he led a dozen people in organizing coups, stealing elections, and other black ops. Among them was Daniel Ellsberg, a Harvard PhD in game theory, who, as a former Marine, at least knew how to shoot straight. Before Ellsberg became the dove who leaked the Pentagon Papers, he was a hawk who spent weekends indulging a self-described “death wish” by walking point on military patrols in the Mekong Delta. Ellsberg had delivered a series of lectures in one of Kissinger’s Harvard seminars, and Kissinger mentioned his younger colleague as someone with whom he was “particularly impressed.”

“The difficulty is that except for the Lansdale group there are few Americans here who can really talk to the Vietnamese,” Kissinger wrote. One day, he watched Lansdale discuss with his group the idea of “revolutionary villages,” the new name for “strategic hamlets,” which itself was an innocuous term for concentration camps. The strategy was based on uprooting peasants from the countryside and turning their rice paddies and fields into free-fire zones, where every corpse could be counted as a success in America’s war of attrition.

After breakfast on his third day in Vietnam, Kissinger again visited Lansdale, who said “that he found conditions in Vietnam infinitely worse than he had expected.” People have been fighting for 25 years and were demoralized by “constant American pressure for reform.” Lansdale called the official reports on pacification “absurd” and said the U.S. military “had not really learned from the French experience.”

Later, at a dinner with Lansdale and his group, Kissinger was given a “gloomy” assessment. Lansdale said that only two of South Vietnam’s 43 provincial chiefs were not “guilty of graft, corruption, incompetence and a complete lack of understanding of the nature of guerilla warfare.” He estimated that only two percent of the country was under government control and even “Saigon was in the jaws of a gigantic pincer like a lobster.” With the possible exception of the ambassador and deputy ambassador, the communists could target anyone they wanted for assassination. “We are watching a society in an advanced stage of decomposition and it is not easy to put things together again,” Lansdale said.

On both trips to Vietnam, Kissinger received warnings of CIA misbehavior there. The first came at a breakfast with Lodge, who had “serious doubts about the CIA operations” that focused mainly on sending “political action teams” into Vietnamese villages. He told Kissinger that he had tried and failed to install Lansdale as Saigon’s CIA station chief. He had been indignantly refused because this was cutting across bureaucratic lines. The CIA saw Lansdale as a rogue figure—and for good reason. In the 1950s, while turning a former French colony into a supposedly democratic country, he had helped Diem steal his first election with 98.2 percent of the vote while simultaneously winking at the Diem family’s drug dealing. CIA airplanes transported heroin out of Laos to Diem family refineries in Saigon. The French had financed their colonial forces this way, and Diem was following their example.

Another warning came eight months later, on Kissinger’s second trip to Vietnam, in July 1966. This time the alarm was sounded by Ellsberg, who had just driven his car, a Triumph Spitfire, through 13 provinces. “Ellsberg painted a grim picture of the situation in the countryside,” where CIA-trained political action teams were being stationed in Vietnam’s 2,000 villages. “The idea of imposing fifty armed men on a Vietnamese village under the kind of leadership that the Vietnamese were getting was simply absurd because it had the practical result of inflicting another bunch of marauders on the villagers.” The United States, said Ellsberg, was “simply shuffling dirt against the wind.”

By this point, Kissinger’s enthusiasm for Lansdale had also begun to wane. He criticized his “egocentric personality” and “the inadequacies of his team. They strike me as second-rate, publicity-conscious, and undisciplined,” Kissinger wrote. Pacification was going so badly that the road from Saigon to the military base at Bien Hoa was closed. Kissinger had to travel the 16 miles by helicopter. He found that wherever the United States had installed itself in Vietnam, the country’s former towns and fishing villages had been turned into “one huge honkey-tonk.” Vietnam’s charms had faded.

U.S. troops carry the wounded to evacuation helicopters amid the bodies of their comrades killed by communist forces in the Ia Drang Valley, November 1965. (Rick Merron/Associated Press)

Despite all he had seen, Kissinger’s war optimism only grew after his second trip to Vietnam. He had come to presume that American forces would prevail. He was already forgetting the cautionary advice he had received during his briefings in Washington and the gloomy reports he had read in the Pentagon’s “for eyes only” documents. As Kissinger noted early in his diary, McNamara adviser John McNaughton “had a file of looseleaf notebooks which are never permitted to leave his office and had never been shown to the State Department.” This had led Kissinger to wonder: “It is not clear to me how one can make national policy with each of the key sub-Cabinet officials guarding their documents for their own personal use without sharing them with either their staff or with the key department.”

Ellsberg no doubt agreed. His position on McNaughton’s staff at the Pentagon would be the apex of his government career, particularly when it came to accessing official secrets. In 1967, when Ellsberg was called back to Washington to help write the Pentagon Papers, he toiled as one of 43 compilers of historical documents—documents that did not include the correspondence and memos in files like McNaughton’s. Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers in 1971, at just the right moment to work as a lever against continuing the war in Vietnam. The secret report was revelatory, but it included nothing of the deliberations that had taken place at the highest levels of government. Ellsberg took great personal risk by leaking the Pentagon Papers, but his whistle would have sounded much louder and much earlier if he had known what was stored in McNaughton’s safe.

Kissinger did know what was in the safe. McNaughton thought the war was insane, a waste of treasure and lives that would end inevitably with the United States’ being forced out of Vietnam. His advice to Kissinger—advice, unfortunately, that the Harvard professor ignored, despite recording it faithfully in his diary—was frank and unsparing: “Let’s face it: At some point on this road we will have to cut the balls off the people we are now supporting in Vietnam, and if you want to do a really constructive study you ought to address yourself to the question of how we can cut their balls off.”

On his last night in Vietnam, Kissinger invited some young embassy staffers to a Chinese dinner in Cholon. Then they hit the nightclubs in Saigon, “where extremely graceful Vietnamese were dancing while on the outside flares were dropping and illuminating the terrain on the outskirts of Saigon. One could occasionally hear artillery rumble. This is an absurd situation.”

“I believe we have to come out honorably in Vietnam,” Kissinger wrote at the end of his diary. This concept of ending the war honorably would be the will-o’-the-wisp that he chased for the next decade. Kissinger had seen in Vietnam a “grim picture, which is not relieved by the fact that I cannot think of a brilliant remedy.”

“If I were a dictator here, I would not know where to begin.”

When he became Nixon’s national security adviser and then secretary of state, Kissinger already knew how the affair would end, and it would not end honorably.