It’s never good when the fire alarm goes off during a tour of a rare manuscripts collection. Our class shuffled out of the climate-controlled room, down the fire escape, and around to the front of the university library. We huddled like Emperor penguins—backs to the wind, faces hoping for sunshine. Longer and longer we waited—this was no drill. My first thought: I hope the fire isn’t in the coat room. My second thought was more appropriate: I hope the fire isn’t destroying all the manuscripts.

We had just seen Milton’s Cambridge graduation signature; Coleridge’s college competition-winning Greek poem; Percy Shelley’s medical bill (sent to Italy, unpaid); Mary Shelley’s attempted life insurance claim (husband’s death at sea not included in the contract). What a knife-turn of fate if we now would not be able to explore the other table of leather books resting on their protective pillows.

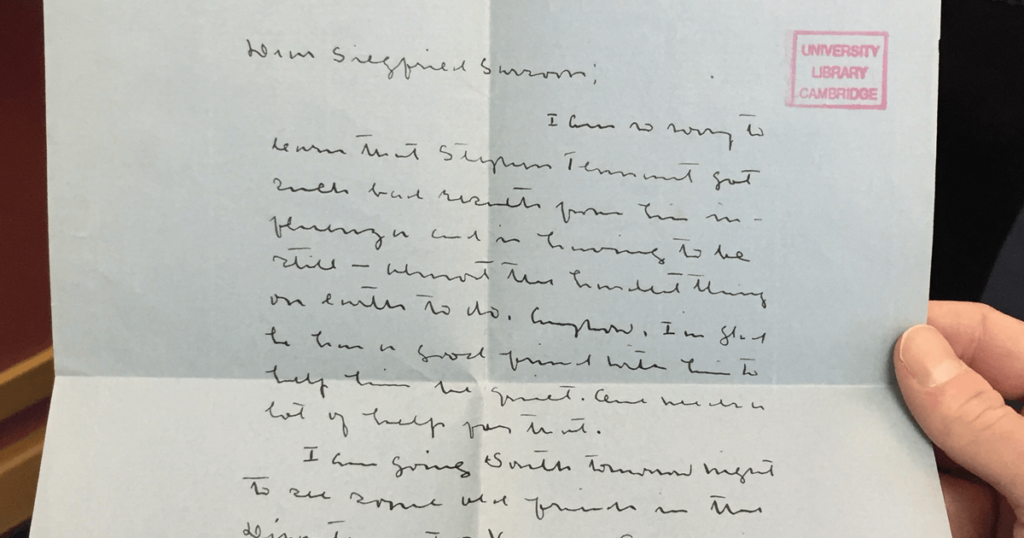

Eventually, firefighters located the blaze in the plant services room and extinguished it. Books (and coats) were unharmed. What was the reward for our damp loitering? Oh, nothing special—just a letter Willa Cather sent to Siegfried Sassoon in Paris, dated July 20, 1930. A missive not included in Cather’s collected letters, recently published despite her wish that the letters be destroyed (perhaps burned?). A blue-paper letter that could ignite my dissertation and leave the ivory tower smoldering.

My academic dream: a wild adventure discovering lost manuscripts, all from the comfort of a library carrel. “Lost Cather letter published and edited by Charlotte Salley”—breaking news soon to scroll across a Times Square marquee. If the fire evacuation had happened after I set my eyes on the treasure, I would—without a blink of doubt, guilt, or remorse—have popped it in my pocket à la The Thomas Crown Affair. Any self-respecting academic marauder would understand.

As it is, I’ll return and make the proper requests for visitation rights. I’ll need time, too, since Cather’s handwriting is atrocious. The T cross is an inch above the rest of Cather. Shelley’s doctor’s writing is more legible. Perhaps that’s why Sassoon tossed the letter to Cambridge—Can’t make out more than a few words of this. I’ll leave it for some poor graduate student to slave over.

Reader’s Note: Every day for the next couple of weeks, we’ll be presenting new entries from “Along the River Cam.” Check here for the latest post.