Obscura No More

How photography rose from the margins of the art world to occupy its vital center

At the midpoint of the 20th century, anyone venturing into a gallery or museum would have been hard-pressed to find any photographs on view among the displays of paintings, drawings, prints, and sculpture. Only a few select museums in major cities—New York, Chicago, San Francisco—considered photographs to be something worth collecting and exhibiting. When photographs were exhibited as works of art, they were far more likely to be found on the dusky walls of coffeehouses and bars than hanging in the white expanses of commercial galleries. Nor, despite their important presence in magazines like Life, Look, and National Geographic, did they much figure on the pages of art magazines or of the few newspapers that could afford to employ art critics.

Scholarly and academic attention was also nearly nonexistent. When I wanted to take a photography class as an undergraduate at Cornell University in the late ’60s, I went to the fine arts department office and asked what was available. “Nothing” was the answer. “We don’t consider photography a fine art.” Confoundingly, the only class on offer, an intro course, was taught in the college of agriculture. I enrolled. The art history survey course I took as a sophomore made no mention of photography. The course textbook, H. W. Janson’s History of Art, did not even list photography in its index.

Fifty years later, one would need to search hard to find a contemporary gallery or museum that does not display photography. Moreover, photography is now the subject of headliner shows at major museums, of PhD theses in art history departments and MFA degrees in studio art programs (including Cornell’s), of books of art criticism that liberally quote from some of the important thinkers of the past century, including Roland Barthes, Walter Benjamin, Michel Foucault, and Susan Sontag. Original black-and-white prints that magazine editors once discarded after using them to make halftone reproductions now command prices at auction of tens if not hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Similarly, the art world itself has been transformed. These days, museums and galleries devote space not only to color photographs as large as any painting by Jackson Pollock, but also to video projections, assemblages of unprepossessing materials that constitute artists’ installations, and interactive performance art. There are now more galleries showing contemporary art than those devoted to the entire rest of art history, with sales at auction houses following the same trend: in the years since photography entered the art world, contemporary art has replaced impressionist and Old Masters painting as the most sought-after, collected, exhibited, and expensive segment of the market. As strange and inchoate as its forms can appear, contemporary art is no longer confined to a small vanguard of true believers; instead, it has developed into a worldwide phenomenon that engages the attention of a broad young audience. Pictures that come from cameras are a large part of the reason why.

Double Rembrandt with Steps by Mike and Doug Starn, 1987–1988 (© 2020 Mike and Doug Starn/Artists Rights Society [ARS], New York)

From the medium’s beginnings, starting in 1839, photographers sought to have their work recognized as art. Indeed, the modern history of photography has been written as a kind of pilgrim’s tale, a major plotline of which is a progressive discovery of the medium’s unique artistic nature following a series of unsatisfying imitative encounters with the arts of painting and drawing.

In the words of William Henry Fox Talbot, one of the two principal inventors of photography, the new medium was no less than a “new art,” yet he called his process “the art of Photogenic drawing,” not photography. The first newspaper report in Paris about the discovery made by the medium’s other credited inventor, Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, begins by saying that “this discovery … will revolutionize the art of drawing.” The writer then refers to Daguerre’s images as “beautiful drawings,” in part because the eponymous term for them had yet to be coined.

Yet for many early observers, the comparison of photography to the work of artists of the pen or brush shortchanged the medium. It fell to commentators like Lady Elizabeth Eastlake, who wrote an influential essay in 1857, to argue that photography’s value should be measured not by existing aesthetic standards but by its own. Lady Eastlake’s article was the first to advance what in the 20th century came to be seen as a modernist aesthetic—that photography could be an art by following its own unique characteristics and abandoning influences and standards from other visual arts, specifically painting and drawing. Rather than compete in terms of flattering depictions of its human subjects, for example, it could excel by providing near infinite detail, which Lady Eastlake noted was one of its native talents.

The idea that the art of photography could be determined by photography itself justified the creation of independent histories of photography written more or less without regard for contemporaneous histories of art. The earliest of these focused more on technological progress than on the makers of outstanding pictures, but Beaumont Newhall’s 1937 The History of Photography, the first real American attempt, inverted that emphasis, placing individual pictures and picture makers at the center of its narrative, even as it recapitulated the notion that scientific and technological breakthroughs helped propel aesthetic ones. Little was said about painting.

This was the history enshrined at the Museum of Modern Art, where Newhall established and led a department of photography in 1940, and the one I read when I was getting seriously interested in the subject. It was an account revivified in the ’60s by John Szarkowski, then the director of the photography department at the Museum of Modern Art, who essentially mixed Lady Eastlake’s argument for photography’s uniqueness with the modernist imprimatur of critic Clement Greenberg. In The Photographer’s Eye (1964/1966), Szarkowski listed five essential characteristics of the medium: the thing itself, the detail, the frame, time, and the vantage point. Contemporary photographers hoping to enter the aesthetic discourse of photographic practice produced work that reflected on these characteristics and, more generally, on “the photographic,” the idea that whatever else a photograph is about, it ultimately is about the nature of photography itself.

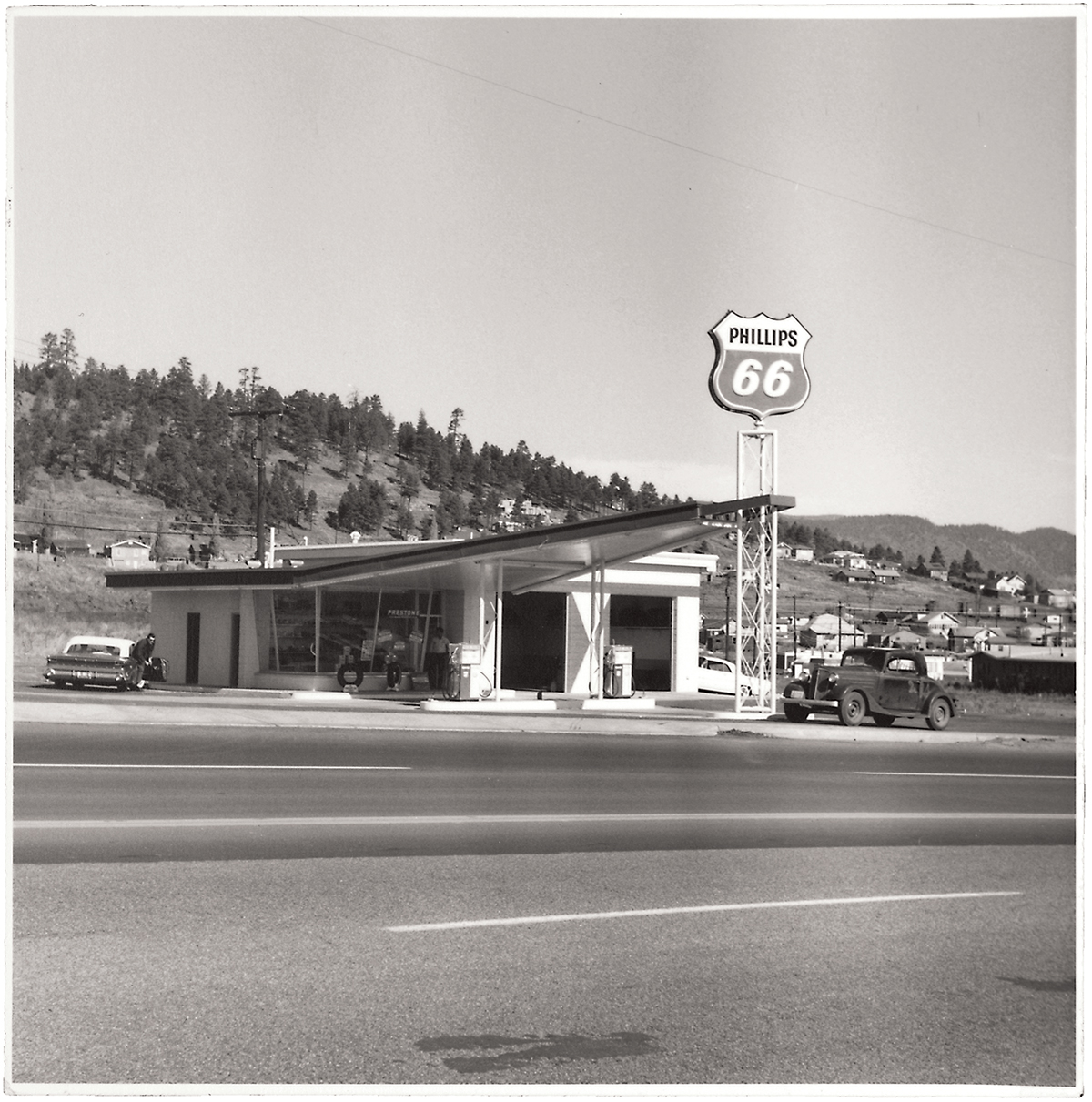

Phillips 66, Flagstaff, Arizona by Edward Ruscha, 1962, from Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963) (© Ed Ruscha, courtesy of the artist and Gagosian)

Photography also developed its own independent exhibition system, arguably of necessity, since it was excluded from the 19th-century salons, with only one exception, the Paris Salon of 1859. As a result, by the end of the century, photographers had established their own salons to present their work to the public as art. In England, an association called the Linked Ring started an annual photographic salon in 1893; similar juried exhibitions happened in Vienna and Paris around the same time, as a new generation of photographers with artistic aspirations replaced the medium’s pioneers. The style they created, photography’s first international aesthetic movement, came to be known as pictorialism.

The pictorialists made their case for photography as an art by producing photographs that looked as if they had been made by hand. The only trouble was that art itself—the kind of advanced art centered in Paris that became known as avant-garde—was changing so rapidly at the turn of the century that these photographers’ efforts came to seem retardataire. Among those caught in the middle was Alfred Stieglitz, a German-educated New Yorker who is often credited with single-handedly promoting the acceptance of the idea of photography-as-art in the first half of the 20th century. The young Stieglitz was a wholehearted pictorialist, a leader of a largely American pictorialist group called the Photo-Secession, until a trip to Paris with Edward Steichen in 1907 introduced him to truly modern artists like Auguste Rodin, Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, Constantin Brancusi, and Henri Matisse. At his modest gallery on Fifth Avenue, called the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession when it opened in 1905 and later known as 291, Stieglitz alternated new European art with pictorialist photography shows.

By 1910, an older and presumably wiser Stieglitz virtually stopped showing pictorialist photography and became a promoter not just of new European art but also of young American artists who responded to Cézanne, Picasso, and the others: Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, and, starting in 1916, a year before the gallery closed, Georgia O’Keeffe. Two months before O’Keeffe’s first appearance at 291, Stieglitz mounted the gallery’s final photography show: the work of Paul Strand.

Strand’s modern photographs, especially his close-in, near-abstract pictures of porch shadows and bowls, revived Stieglitz’s interest in the medium. Like Lady Eastlake before him and Szarkowski after, Stieglitz came to believe that the art of photography could be understood only in terms of photography. Strand’s work, Stieglitz found, was “devoid of trickery” of the sort that pictorialists used in printing to emulate the atmospherics of a James McNeill Whistler painting; it was “pure” and “direct” in the sense that its appearance, even when abstract, could be readily recognized as photography.

But there was a small catch to Stieglitz’s ambition for modern photography: the almost complete absence of a market for photographs. This led artists like Strand’s friend the Precisionist painter Charles Sheeler to minimize or even renounce the importance of photography in their work. In the early ’30s, Sheeler’s gallery dealer told him to stop showing his photographs, lest his paintings be seen as copies of them. The dealer’s interests were clearly financial, but they also reflected what was a long-standing prejudice against photography in the art marketplace. Photographs could be seen but not sold.

Untitled #96 by

Cindy Sherman, 1981 (Courtesy of the Artist and Metro Pictures, New York)

What might be called the modernist apartheid system for photography was not entirely hegemonic. In Europe during the period between the world wars, photographs were a big deal, as evidenced by a number of vanguard art movements, Russian constructivism, Dada, and surrealism among them. At the German Bauhaus, László Moholy-Nagy was at the center of an art and design revolution in which the camera was seen as a powerful tool for reorganizing consciousness. What Moholy-Nagy explicitly called “the new vision” became a central part of Bauhaus teaching.

The surrealists Max Ernst, Man Ray, and Maurice Tabard had their work included in a large 1929 exhibition called Film und Foto, in Stuttgart. That show is legendary because it brought together new and experimental photography from throughout Europe with some from the United States, with contributions by Imogen Cunningham, Edward Steichen, Ralph Steiner, and Edward and Brett Weston. Photography, as artist Suzanne Pastor has written, “became part of the modern chic of the twenties,” and it also represented, for many, the radical new future for the visual arts. Photographs also played a role, albeit minor, in the 1936 exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism, organized by Alfred H. Barr Jr. at the Museum of Modern Art, which mixed them together with paintings, drawings, and films.

Sadly, the rise of the Nazis in Germany and World War II brought an end to these essentially experimental art movements and consequently an end to photography’s budding status within the art world. The migration of artistic talent to the United States included Moholy-Nagy, Ernst, Man Ray, and many of the European artists in Film und Foto, but unless they worked as magazine photographers, their work was largely marginalized. After the war, photography was consigned mainly to the printed page, in the form of picture magazines, fashion magazines, and newspapers. When it was exhibited, it was often as a nostrum of conventionality and commonality, as in the wildly popular 1955 show The Family of Man, organized by Steichen at the Museum of Modern Art. The role photography played in Dada and surrealism and at the Bauhaus was largely overlooked until, like a recovered memory, it was recalled amid the growing interest in the medium in the ’70s and ’80s—the decades in which I enter the story.

Photography’s rise within contemporary art—and contemporary art’s simultaneous rise to prominence—encompasses a period coincident with my own life. I was a child of an amateur photographer and a member of the first generation of Americans to grow up with television. I learned to dance by watching Dick Clark’s American Bandstand. Father Knows Best and The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet provided aspirational models for measuring my upbringing. Waiting my turn at the barbershop, I would devour dated copies of Life magazine, and my interest in visual experience developed alongside my attraction to literature and writing.

I arrived in New York City in 1971, prepared to be a proverbial penniless poet, although I had achieved some résumé cred by working part-time as a newspaper photographer at the end of my graduate writing program in North Carolina. The most famous photographer of the moment, Diane Arbus, committed suicide in her West Village apartment at about the same time that I moved into my first apartment on the Upper West Side, but I would encounter two of her peers, street photographers Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander, prowling midtown in search of telling moments in the human comedy. They were famous, at least in my mind, for being shown at the Museum of Modern Art. Arbus was about to have her posthumous retrospective there. And a new breed of galleries had just sprung up, devoted to selling photographs as works of art. Within a few years, I took advantage of the new interest in writing on photography, cutting my teeth as a critic at Art in America before becoming a contributor to the SoHo Weekly News.

Visiting friends downtown, I discovered a whole other world: in SoHo, artists my age or slightly older were making art that I could barely recognize as such, filling old industrial spaces with tree trunks and piles of dirt and creating a scene in which any manner of activity—rappelling headfirst down the side of a building, cooking, masturbating, talking to oneself—could count as an artwork. Much of what was happening was recorded with cameras, producing photographs, films, and (soon enough) video. The art world was in ferment, reconfiguring itself to a new age, assimilating a new generation, my generation.

It wasn’t only the art world in upheaval. The later ’60s and early ’70s were marked by the civil rights movement, the war in Vietnam, a growing feminist awareness, and a consciousness-changing youth movement that coalesced around rock music, sex, and drugs. Some of this I had experienced firsthand, going to Bob Dylan, Rolling Stones, and Janis Joplin concerts, traveling to anti–Vietnam war “mobilizations” in Washington, D.C., visiting San Francisco during its 1967 Summer of Love, inhaling illegal botanicals. But much of it I had assimilated through photographs.

I saw images of Black protesters in Birmingham being sprayed by high-pressure fire hoses, a Marine dying in the Khe Sanh mud with his blood recorded in living color, a Vietnamese girl running naked and burned from her napalmed village, and, on the May 18, 1970, cover of Newsweek, a distraught young woman on the campus of Kent State University kneeling next to the body of a student killed by a bullet from the Ohio National Guard. These stills were part of a broad, essential-seeming media environment, novel then but now exponentially denser, that included not only film, television, and picture magazines but also rock album covers, psychedelic concert posters, and R. Crumb underground comics.

In one instance, my firsthand experience and an iconic photographic image coincided directly. The Pulitzer Prize–winning news photograph of 1970, taken by Steve Starr of the Associated Press, showed a group of my Cornell classmates leaving the campus student union on April 20, 1969, with long guns in their hands and bandoleers of bullets across their shoulders. All were Black, and they had been protesting on-campus discrimination; purportedly they armed themselves after some white students threatened to use force to end the occupation of the building. Unfortunately, the mere sight of weapons played into some people’s fear that civil rights might lead to horrible and violent outcomes, even on bucolic college campuses.

I reacted differently. I knew not only that the image was laden with fraught symbolic significance, but also that the students depicted were mostly suburban kids who did their best to look fierce but barely knew a rifle’s sight from its safety. I recognized then, if I hadn’t before, that photographic meaning was contingent rather than absolute.

The assassinations within a five-year span of President John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr. had added more grizzly images to my generation’s memory bank, no doubt troubling our ability to fit into the existing order of things as much as they instilled an appreciation of life’s tragic dimension. That art in all its forms—visual, written, performed—would be radically altered in this convulsive climate should have come as no surprise. What was surprising, at least at the time, was the starring role that photography, and its younger partner, video, would come to play in this transformation.

It is no exaggeration to say that photographs snuck into view in contemporary art, starting in the ’60s. They were first seen as paintings, in the silkscreens of Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol, or as documentation, in a wide range of new and transgressive art styles such as earth art, conceptual art, and performance art. Artists who relied on photographic documentation, followed by their dealers and collectors, began to notice that photographs were interesting in and of themselves. Plus, photographs could be easily made, exhibited, and reproduced, something that couldn’t be said for earthworks or performances.

It helped, too, that photographs were part of what was fast becoming an overwhelming domain of camera images, an “image-world,” in Susan Sontag’s phrase, that encompassed movies, television, magazine picture essays, advertisements, and everyday snapshots and threatened to replace firsthand reality. In the ’70s, theorists, critics, and artists all started to look at photography with a fresh interest, recognizing it as a medium not just for making pictures but also for making meaning. It wasn’t long before contemporary art galleries were exhibiting photographs and video as a regular part of their schedules.

At the time, the art of photography was best represented in the public imagination by glorious prints of glorious nature made by the likes of Ansel Adams, but it also encompassed street photography and other modes of factual documentation. The new photography was different. Another photographer named Adams—Robert—showed us landscapes filled with suburban houses. John Pfahl, also of the new generation, made beautiful color pictures of what he called “altered landscapes,” altered because he put objects into the scene to produce amusing optical conundrums, like a hayrick that was visually transformed by a well-placed skein of rope into an outsize ice cream cone.

James Casebere, David Levinthal, Cindy Sherman, Laurie Simmons, Sandy Skoglund, and others started staging their pictures in studios and on tabletops, taking cues from commercial studio photography and Hollywood scenography while rebelling against the belief that good photographs were unmediated slices of reality. Most radically, there were artists who decided to take photographs of photographs. Sherrie Levine and Richard Prince impertinently claimed the results as their own, leading to much umbrage among older photographers and many lawsuit-threatening letters from copyright attorneys. The point of this appropriation wasn’t theft, however, but to point out how overburdened we are with images, to the extent that we don’t often recognize what they are selling us, or why.

By the end of the ’80s, the distinction between what was photography by artists and art by photographers no longer seemed to matter. What did matter was the impact of photography and video on the very conception of what contemporary art was. No longer a prisoner of formal proscriptions about what it should look like, contemporary art had become more diverse, more open to a variety of voices, and more reflective of cultural concerns, including, but not limited to, the experiences of women, gays and lesbians, African Americans, Latino people, and first- and second-generation immigrants. For many, photography and video were ideal tools for expressing the complexities of their lives. For others, lens-based media were the harbingers of a new media culture, one now fully realized in the inescapable 21st-century environment of the digitally networked image.

I have come to recognize how fortunate I was to have landed in New York when I did, for I was able to witness photography’s transformation from a minor role to a lead actor in the drama of 20th-century art. When I started paying attention, art and photography were separate domains, and when I began writing for The New York Times (which I would do for most of the ’80s), I was assigned to cover photography exhibitions and books while the paper’s other art critics covered everything else. My territory initially was a small enough world that I got to meet and interact with many of the major players of an older generation—Berenice Abbott, André Kertész, Russell Lee, Helen Levitt, W. Eugene Smith, Ansel Adams himself—and to rub elbows with Peter Campus, Ralph Gibson, Nan Goldin, Duane Michals, Cindy Sherman, Carrie Mae Weems, and scores more contemporary artists.

The eradication of photography’s separate-but-not-quite-equal status within the art world—its triumph as an art form—has been important, but equally important is the crucial position that photography and other lens-based media have come to occupy throughout our culture, not only by representing it but also in large part by producing it. Given that camera images are practically inescapable and incalculably influential, is it any wonder that many of the most creative artistic talents of the past 50 years have devoted themselves to showing us not only the medium’s aesthetic possibilities but also its paradoxes and peculiarities.