Kneeling has reentered American political discourse. In the protests after George Floyd’s murder, Black Americans approached police officers and knelt. To lower one’s body in front of a man wearing riot gear and weapons, a man who is vibrating with the knowledge that today may be the day he will use them, takes a rare kind of physical courage. In some ways, it is an escalation of the raised hands and chants that followed Michael Brown’s killing in 2014: “Hands up, don’t shoot!” It is an attitude of petition and surrender transformed into an act of defiance. At once vulnerable and insistent, the posture demands a commitment from the kneeler and, I imagine, wrests an emotional reaction from the officer that must be very difficult to suppress.

This emotional urgency is certainly part of the gesture’s power. But part of its power is also in its historical resonance. I say that kneeling has reentered our discourse because it calls to mind old images—older than last summer, older than Colin Kaepernick’s steadfast protest on the football field and the angry responses he provoked—an ancient iconography of Black men and women on their knees that is worked deeply into our visual culture.

The silhouette of the Black person kneeling is a cliché in Western art, one that has been demeaning to Blacks more often than it has been empowering. Like the other Procrustean caricatures we encounter in daily life, it limits us to something less than full humanity. Its appropriation in our recent protests shows yet again Black Americans’ capacity to master the badges of our oppression in powerful new ways. We are a people, after all, who took the castoffs from other men’s tables and the tough, gristly refuse of the slaughter, and made a cuisine that became the quintessentially American food. We are a people who created glad music about our pain, and that music, the blues, now underlies all of America’s homegrown genres. Our kneeling during the George Floyd protests, while holding signs that read, “Get your knee off our necks,” was another dramatic proof of our ability to transform a painful inheritance into a new narrative.

Viewed in the broader context of Black creative power, the re-emergence of this gesture can be taken as a threat, not only to subvert and reclaim individual confrontations with power, but essentially to remake the American narrative. To understand where we are now, therefore, it may be worthwhile to consider the history of this iconography and to reflect on what it means that we reenacted it in the summer of 2020.

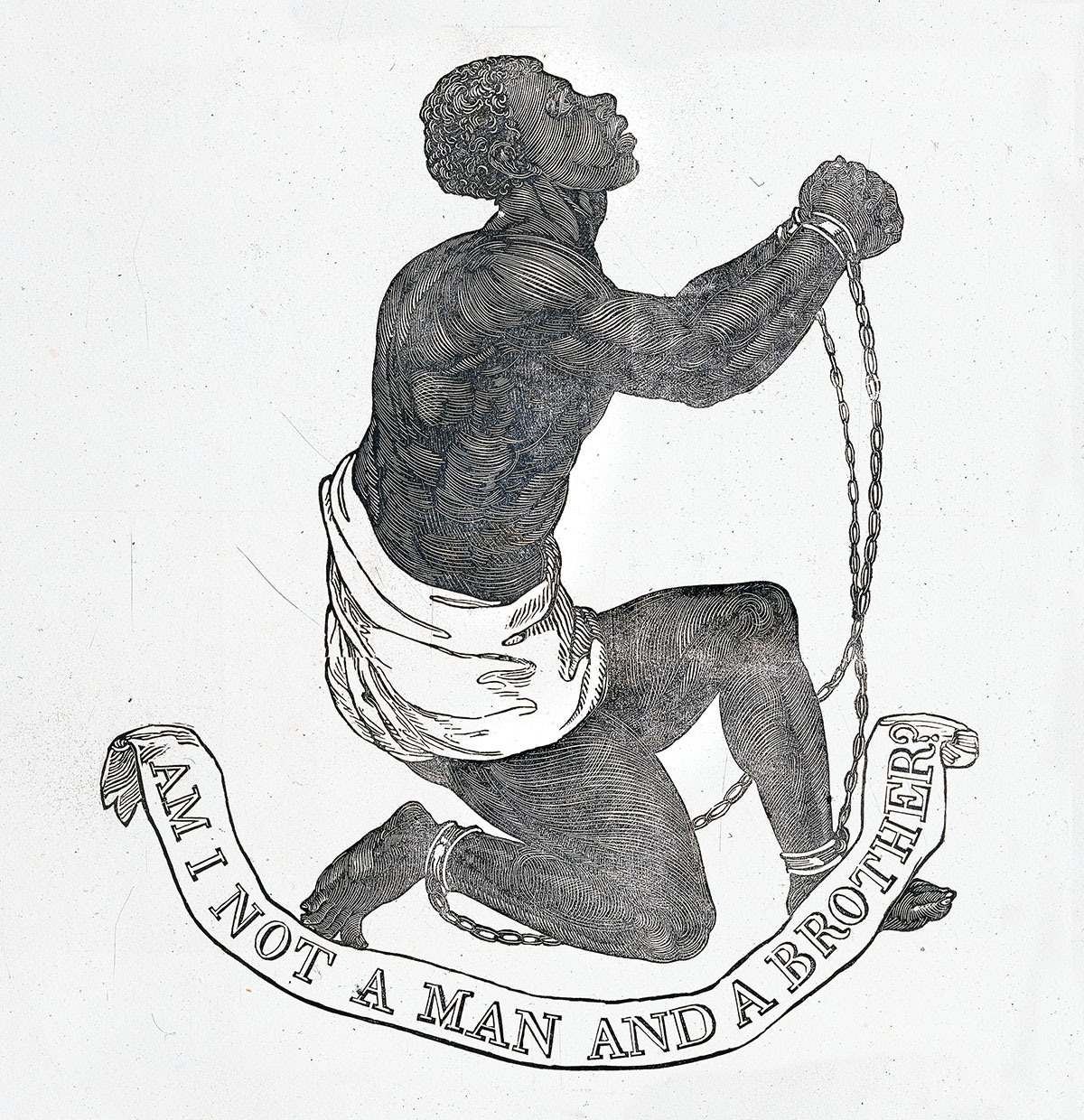

The version of the kneeling figure that first comes to mind, and the one that most directly influences our time, is on the emblem of the British and American anti–slave-trade societies. Produced in the late 18th century by Josiah Wedgwood, it depicts a Black man kneeling barefoot and in rags. His wrists are fettered, and a chain dangles from his uplifted, clasped hands. The text, “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” arches across the scene. Later versions by all-female abolition societies made the figure a kneeling Black woman, with the text “Am I Not a Woman and a Sister?” As a popular signal of sympathy for the cause, the emblem appeared on everything from pottery and other household goods to wax seals and fobs, shoe buckles, hair ornaments, and intaglio jewelry. It was even struck into repurposed low-denomination coins, which society members exchanged as tokens and keepsakes.

This emblem of the British and American anti–slave- trade societies, produced by Josiah Wedgwood, appeared on many objects. (Library of Congress)

Although he became ubiquitous, the slave on Wedgwood’s seal was hardly the earliest example of the kneeling African in Western imagery. His ascendance represents the decline and diminution of a more ancient figure: Balthazar, one of the three magi who journeyed from the East to honor the newborn Christ. Early Western depictions of the Adoration of the Magi portrayed the three kings as European, but from at least the 14th century, artists began to use these paintings to showcase their skill at depicting the different races and ages of man. Melchior, sometimes aged, was portrayed as Arab; Caspar, in the prime of his life, as European; and Balthazar, sometimes a youth, as African. The fashion for depicting Balthazar this way began in northern and Germanic Europe, extending south and east over the centuries and finding its way into Italian art by the 16th century.

The Adoration scenes are as complicated as a Roman triumph but much more intimate. They contain a menagerie of animals both exotic and domestic, cloth and other materials of every texture and hue, and a crowd of mixed ages and conditions displaying a spectrum of emotion, including love, awe, fear, distraction, confusion, and incredulity. These are scenes of great and boisterous transition: men on a long journey have arrived or are arriving; a woman has just become a mother; a crowd of disparate strangers is uniting in a shared focus and a shared conversion; a god is becoming flesh.

Peter Paul Rubens’s The Adoration of the Magi, 1624 (Art Collection 2 / Alamy Stock Photo)

In some of the most famous versions, Balthazar is the third king in line and not yet kneeling to the infant Christ. In versions by Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Balthazar stands austere, in white robes, with abstracted, star-addled eyes. This dark, elegant, and otherworldly man provides a shock of black and white in the ruddy human scene, contrasting with the pink of the fleshy baby, the yellow and brown of the straw and the donkey, and all the other ochre colors of men and animals huddled around the door of a stable and recent birthing room. Balthazar’s exoticism and his reserve communicate, more than anything else in these paintings, that something extraordinary has just happened, and that the divine has intervened into the world of men. A 1624 painting by Peter Paul Rubens goes so far as to put Balthazar at the center of the scene. Rubens’s African Balthazar, turbaned and richly draped, stands with an arm akimbo, thrusting his large belly forward, his widened eyes darting sideways to the infant Jesus. One cannot believe that a man this proud will kneel. But it is Balthazar’s magnificence, even amid all the other visual interest of the scene, that effectively communicates the Adoration’s central theme. Jesus’s greatness is confirmed because we are certain that even this towering figure will bend the knee.

Many renderings of the Adoration show the moment when Balthazar begins to lower himself—an Albrecht Dürer print captures this—and others show the moment when he finally kneels. The Italian Baroque painter Bartolomeo Biscaino has my favorite example of this final moment. In his canvas, Balthazar looks like an uncle kneeling to meet a new nephew. With one hand, he offers Jesus his gift. His other hand is over his heart, which could be a pledge of fealty, but instead expresses something more personal than that: the unconscious gesture of a man moved beyond every expectation. His gaze connects with the baby’s, and their connection is the painting’s chief emotional content.

The Adoration of the Magi (1650/1655) by Bartolomeo Biscaino (Strasbourg, Musée des Beaux-Arts/Musées de Strasbourg, M. Bertol)

This kingly, orientalist version of the kneeling Black man survived into the 19th century. Thomas Jones Barker’s 1863 painting The Secret of England’s Greatness features a colonialist fantasy on a large scale: a handsome African man in regal dress kneels in grateful awe in the throne room at Windsor Castle to receive the gift of a Bible from Queen Victoria. This work is certainly offensive, but that should not blind us to some points of interest. The Secret of England’s Greatness is a version of the Adoration, with Queen Victoria draped in blue to suggest Mary, Prince Albert in the background as the resentful Joseph, and two English ministers behind the African dignitary standing in well enough for the other magi. In this iteration of the scene, Victoria and the figure meant to personify Africa are visually paired. She is wearing pearls, as is he. She stands before a lion throne; he wears the pelt of a big cat. She is adorned with feathers, as is he.

Like the Old Masters who painted the Adoration, the artist of The Secret of England’s Greatness understood that highlighting the African’s majesty would further exalt the object of his veneration. In this late version, the Black man’s genuflection is a voluntary gesture, like that of the knighted vassal kneeling to promise his strength to his monarch, or that of the bridegroom kneeling to his bride. It is the obeisance of a figure depicted as Victoria’s equal—in stature, in vibrancy, in beauty. The implication of his physical equality, along with the effort to pair them visually, is that the only explanation for his obeisance is her overwhelming moral superiority or divine right to rule. His grandeur is what makes his posture meaningful.

Thomas Jones Barker’s 1863 The Secret of England’s Greatness portrays Queen Victoria giving an African dignitary a Bible.

By this late date, however, the regal Balthazar had largely been eclipsed, as the genuflecting Black man featured on the seal of the abolition societies began to predominate in Western art and imagery. It is a stark transition from the African magus to that pathetic figure. In the Adoration, the black man represents one part of diverse humanity united for the first time under a new divine regime. The figure on the antislavery seal has been shorn of his finery and exiled from that boisterous scene. Perhaps the rest of the human and animal kingdom continues in its celebration of the Nativity in another place, but the Black man has been cast out. In this respect, the symbol of the abolitionist movement was ironically in sync with the emergence, during the Enlightenment, of new intellectual justifications for the enslavement and oppression of Black people.

Western depictions of black majesty fit more neatly into eras of European thought and culture committed to the belief that people were defined essentially by distinctions of social class. In those earlier eras, the idea that black men might also have kings as well as peasants was no threat to European hierarchy. If anything, it implied an argument, from universal adoption of the principle, that those born to rule should rule. During the Enlightenment, however, a philosophic rejection of notions of inherited social caste created an appetite for new explanations supporting the West’s enduring social and economic commitment to Black slavery, explanations rooted in taxonomic differences between races of man. Hieronymus Bosch’s austere and magnificent Balthazar from the 15th century would have been an awkward fit in the late 18th century, the inauguration of an era newly committed to belief in the scientific inferiority of Blacks.

In “Am I Not a Man,” the Black man of the antislavery seal asks only for acknowledgment that he is at least a fellow human. In his insistence that he is also “a Brother,” he pleads for readmission into the community gathered around Christ from which the image exiles him. From a monarch, the Black man has been transformed into an object of sympathy, an object of mercy, the proving ground for the moral rectitude of the white race to whom the appeal is addressed. Indeed, this is the most striking distinction between the original iconography and the version on the antislavery seal: the man who once knelt only to God now kneels in petition to a man—and the white addressee of his appeal is not even pictured. The assumption of the seal, domineering and inescapable, is that there is no need to depict him because the consumer of the image is a white person. And the loneliness of the Black figure, the austerity of his landscape, further transforms the viewer: from a participant represented among the magi and enfolded into a scene that overwhelms the senses, into a detached voyeur of a stranger’s degrading appeal and, of course, into the arbiter of that stranger’s fate.

This image of a Black man on his knees was what the antislavery societies of Britain and America assumed would make the most effective appeal to a white audience wavering on the point of admitting Black people’s right to ownership of our own bodies. And in a sense, we have been pictured in that position ever since.

The icon of the kneeling man is hundreds of years old, and yet it is still here, one part of that difficult past that we Americans drag with us from age to age. History is not past, as Ralph Ellison observed in the introduction to his great American novel, Invisible Man. “Furtive, implacable and tricky, it inspirits both the observer and the scene observed,” including its “artifacts, manners and atmosphere.” As one might expect, we feel the past as both a social and a political burden. But it is, unavoidably, an aesthetic one as well.

What it means for a Black person to live under the shadow of an inherited aesthetic is that when white people see us, they tend not to look for cues about our interests or personality. It may never occur to them to be curious about who we are. Instead, we are categorized by reference to a catalog of types. A Black person among white strangers expects to confront a ready-made summary of not who but what he must be, before he has spoken a word. The Black parent at the soccer game experiences this, the shopper at the store, the teen whose white friends stop inviting him to play once, in their parents’ estimation, he transitions from cute kid to shady character.

Indeed, the kneeling at our recent protests implicitly attested to a truth that all Black men must come to terms with starting in early adolescence: that the Black body is a fearful colossus to the white officer. It is only by getting down on his knees that a Black man has a chance of having his words attended to, instead of the imagined threat his body poses even at rest. Black women also face impenetrable prejudgments; we are the Jezebel, the troublemaker, the sassy sidekick, the workplace virago, the mammy, the church lady, the beggar. The Black adolescent girl must find herself while pressing through a smothering forest of these inert bodies, set types that strangers treat as more obvious and vibrant than the person in front of them. She must find her voice while white people continue to speak, react, and respond to a caricature, regardless of what she tries to say.

Perhaps the most common assumption in polite spaces is that we are there to serve. In a 2014 interview, Michelle Obama discussed her experience at a highly publicized photo-op in a store. The only person to approach her did so to ask for her help fetching something from a shelf. That shopper “didn’t see me as the first lady, she saw me as someone who could help her”—that is, as an employee. In the same interview, Obama mentioned a time her husband was mistaken for the wait staff at a black-tie event. It was affirming to hear her talk about this, because of course it happens to me too. When I’m out shopping, other customers often approach me to ask for a size or to get something from the back of the store.

This may seem trivial, and indeed, some news outlets mocked the first lady for complaining about something so small. But if it isn’t your experience, it might be hard to imagine how it feels to be constantly interrupted by strangers in public places telling you they see you as a servant. No quantum of prestige confers immunity. During a year I spent as a Supreme Court clerk, tourists had plenty of opportunities to tell me their estimation of my place in the building. A white family called out to me once as I passed through the cafeteria in my navy suit, asking whether I worked there. When I proudly confirmed I did, they asked me to fix the coffee machine. Another time, a white father and son on their first trip to D.C. shared an elevator ride with me. Referring to the ornate elevator doors, the father ventured, “They don’t make you polish all that bronze, do they?” I was wearing my court-appropriate attire and carrying a stack of legal research. But when they saw me and my brown skin in that exalted setting—the house of the state—they assumed that I belonged on my knees.

Those Black women who survive, the poet Audre Lorde said, do so in spite of living in a world that “takes for granted our lack of humanness, and which hates our very existence outside of its service.” And we are in service, whether or not the summary archetype we are filed into is “servant.” We are equally serving a lazy narrative when we are called upon to play any of the other fixed types in the limited cast of possibilities. And I don’t think Lorde’s word hate overstates things. When a stranger reflexively assigns me to a category, it may seem more lazy than mean-spirited in the moment. But the repeated, unreflecting refusal to see me as an individual does begin to feel something like hatred. At best, it reflects a deep anxiety about the fact of my personhood outside of these roles.

It doesn’t take much to shift, in the white stranger’s estimation, from a useful type to a threatening one, from servant to pariah. One afternoon a few months after my clerkship, while I was on maternity leave from a law firm, I wheeled my stroller to Washington’s Union Station to pick up my older child, whose teacher shuttled him to this stop on the Metro after preschool each day. I wore what I suppose most people wear on maternity leave, and I hadn’t bothered with makeup. Unfortunately, my cell phone died on the way to the station, and my son and his teacher weren’t there when I arrived. As I stood in our usual spot in the busy station, I became more and more anxious. I didn’t want to walk away to find a clock, because I didn’t want to miss them when they arrived.

I thought my anxiety might be getting the better of me, so I asked a passerby what time it was. He turned his head slightly at my voice but didn’t answer me. This happened again with the next person, and again and again. A stream of white professionals ignored me as I asked one after the other, “Excuse me, do you have the time?” I suppose they assumed this was my ploy to get them to engage with me so that I could beg for money. After a white woman my age passed me closely, ignoring me, I heard a histrionic note in my voice when I called out the question again. She turned around without stopping—actually walking backward—and answered my question with a handwringing, apologetic gesture before hurriedly continuing on her way. When my son and his teacher finally arrived, I learned that they had boarded the Metro in the wrong direction. Everything was fine. My three-year-old, putting his own interpretation on my mood, thought it was silly I was so upset about the mishap, which he had experienced as a hilarious adventure.

There is something of a debate at the moment about whether America is “a racist country.” But consider, white reader: do you have to dress up in order to get the time of day from your countrymen? Can you walk or jog around an unfamiliar neighborhood in casual clothing? The caricature sorting we are subjected to is blunt and unsophisticated. We have to make quite obvious at first glance that we fit one or the other stereotype if we want to make sure to be favorably sorted, to be free from harassment and indignity, or, when dealing with armed men, to be safe from murder.

If you’re not Black, you may not understand how it feels to live among a people who expect you to embody two-dimensional caricatures, to act out icons, types, and figures. When it’s not life or death, it is still a constant distraction and insult, made more, not less, obnoxious because it is unthinking and unintended. When a white person alerts us to the part we’ve been assigned, we face a choice whether to play along to get along. There are social or professional consequences that come with asserting a self. To be unsurprising, to comply with expectations: this is the survival tactic of a slave living in her master’s house. It’s all the more tragic when, having been raised in a theater with such a limited repertoire, we come to believe we are the part. If a community insists on seeing a young Black girl as an oversexed, sassy troublemaker, and later, as a demanding, long-suffering disciplinarian, eventually she may give in and express all the emerging power of her voice in that frame.

And yet, there have always been Black people who have managed to take these caricatures and make good use of them, to grab the end of the descending lash and pull.

This year I read Nell Irvin Painter’s moving biography of Sojourner Truth for the first time, and I was struck by a few vivid examples from the life of that exceptional woman. What made Truth exceptional was not that she managed to avoid the relentless categorization and diminishment of her personhood by white Americans. In fact, Painter reveals, the most famous moment of Truth’s life probably comes down to us altered and squeezed to fit into the frame of one such caricature. If an American learns one thing about the great 19th-century abolitionist, it is probably the first lines of her famous “Ar’n’t I a Woman” speech from an 1851 women’s rights convention in Akron. The version of this speech that historians and elementary school teachers have traditionally quoted has been the one the white abolitionist Frances Dana Gage narrated in a newspaper column in 1863, more than 10 years after the fact. In this widely publicized version, Truth pointed to a man in the audience and said, “Dat man ober dar say dat woman needs to be helped into carriages, and lifted ober ditches, and to have de best place eberywhar. Nobody eber helps me into carriages, or ober mud-puddles, or gives me any best place!”

Raising herself to her full height, and her voice to a pitch like rolling thunder, she asked, “And ar’n’t I a woman? Look at me. Look at my arm,” and she bared her right arm to the shoulder, showing its tremendous muscular power. “I have plowed and planted and gathered into barns, and no man could head me—and ar’n’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man, (when I could get it,) and bear de lash as well—and ar’n’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen chillen, and seen ’em mos’ all sold off into slavery, and when I cried out with a mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard—and ar’n’t I a woman?”

What modern Sojourner Truth biographers such as Painter and Carleton Mabee have shown, however, is that these probably weren’t Sojourner Truth’s words. Truth had only five children, for one thing. One of them had been torn from her and sold into the Deep South—a heartrending episode that, along with her determined efforts to get him back, helped to shape both her public and private character. Painter found no other instances in which she claimed more. Furthermore, Gage’s version had Truth speaking with a heavy southern accent, which is what white audiences may have expected if all they knew about Truth was that she was a former slave. But Sojourner Truth was raised in New York State and spoke Dutch as her first language. Proud of her diction, Painter tells us, Truth resented being quoted with an accent.

The renowned 19th- century abolitionist Sojourner Truth, shown here in an 1864 portrait by Matthew Brady (IanDagnall Computing/Alamy)

A truer version of the speech, Painter argues, was the one synopsized directly after the event in an 1851 article. In that report, Truth’s speech focused closely on women’s equality to men and women’s right to the ballot. It did not have the striking refrain, “Ar’n’t I a woman”—that repeated insistence that Truth belonged in the category “woman.”

Gage’s misquote stripped Truth of her particular cultural markers, her difficult and unique biography, and her authentic political ideas. Instead, it forced Truth to speak, “Am I Not a Woman and a Sister?” There’s no telling why Gage did this. Perhaps she thought that this was the version of Sojourner Truth to which the public would best respond. It’s also possible, though, that Gage was so taken with the two-dimensional caricature on her movement’s emblem that she had difficulty seeing a Black woman in any other way.

Painter’s biography also reveals moments in which Truth triumphed over these archetypes, not by escaping them, but by subverting them for her own expressive purposes. My favorite example is the time when an audience did call her sex into question. In the mid-19th century, it was not uncommon for critics to challenge politically active women by insisting that they were male agitators in women’s clothing. According to Painter, this happened to Truth in 1858 in Indiana, where she had just given a speech on abolition. A loudmouth insisted that Truth was really a man, and this notion spread through the crowd until finally it was put to a voice vote whether she should have to prove her sex by stepping aside with women from the audience to show them her breast. The crowd answered this proposal with a boisterous “Aye.” This would have been the moment for an “Ar’n’t I a Woman” speech if there ever was one.

But Truth had a different reaction. She stood up before the crowd and opened her top. She told the shocked audience that she had fed many a white babe from these breasts, that some of them had grown into better specimens of manhood than the people she saw in the crowd—would any of them like to suck? Standing there exposed, she told them that she had nothing to hide, and that “it was not to her shame that she uncovered her breast before them, but to their shame.” Painter points out that in that moment, Truth called on another powerful visual theme. When Black women were sold, they were often forced to stand on the auction block with their breasts exposed. We cannot know whether Truth’s own memories of being auctioned and sold included this specific humiliation. But Truth knew how to embody a stock role. She knew how to use it to express her rage, her personal power, to mock her audience, to throw their pretensions to gentility in their faces, to confront them with the context of the demand they placed on her, and the indignity and moral enormity of the request given that context.

Sojourner Truth could use the caricatures at hand, such poor representations of the self, for vivid and undeniable self-expression. A poet can make a whole world out of 17 syllables; an artist can represent movement and life with a pencil line; a great musician can perform on a broken instrument. A great mind will communicate itself with the vocabulary available. We may wonder what a person like Truth might have taught the world if she hadn’t been constrained to represent her humanity with such a limited palette—but set that aside.

Here’s the point: for those of us who survive it—that is to say, for those of us not driven into a hole underground like Ralph Ellison’s deranged hero in Invisible Man—an upbringing fettered with these expectations is a harsh but effective training in narrative and performance. A person schooled in this theater has learned, by brutal necessity, every line. We have been picked up and put down like props, lost and found again, expected to play one bit part and then another, now helpful, now frightening, to do, in short, whatever the main character may require for support of his fragile ego or the fulfillment of his heroic fantasy. And, unlike those who cast themselves in the part of the so-called master race, a role that flatters the adolescent tendency to think of oneself as the protagonist of every story, and who may therefore never learn to confront the distinction between that role and the self—we know for a certainty that it is all theater.

A few weeks ago, I went to the Art Institute of Chicago to take a look at the 1827 portrait of the Black actor Ira Aldridge. According to the four-volume biography by historian Bernth Lindfors, Aldridge was born free in New York City in 1807 and earned wealth and fame in Europe for his acting ability. His first successes in England were for his portrayal of Shakespeare’s Othello and other African dramatic parts. He then added Shylock and Richard III to his repertoire, which he performed in white makeup. During part of his career, he took his act on the road to cities around England, playing scenes from Othello, followed by a comedic role as a shiftless and bumbling slave. As an article by the critic Alex Ross points out, critical assessments of Aldridge often focused on his race. But Aldridge had a knack for turning a profit off his audience’s racial fascination. After a white American actor in blackface found success with an act about an African American trying and failing to pronounce Shakespeare, Aldridge simply added that self-mocking role to his own repertoire.

He used every suffocating caricature, every stereotype that put Black people in a box or that justified their continued oppression, to burnish his own star and to win a life for himself that was enviably unfettered. And although some historians have criticized him for adopting the skits of minstrel shows as part of his act, by pairing such doggerel with the high drama of Othello, he highlighted the artificiality of each. Such juxtapositions must have suggested to audiences that none of these set types essentially captured Black humanity. When he cast off one persona and put another on as easily as changing his clothes, he must have demonstrated, at least to some, that there was a Black human in front of them who could not be summarized by any of the parts he played.

As Aldridge’s star rose in England, reviewers saw in his performances a powerful argument for abolition. In the Art Institute’s portrait, titled The Captive Slave, John Simpson, a British artist friendly to that cause, has painted Aldridge as the icon we’ve been discussing. Aldridge rests on an ill-defined ledge and against a shadowed background in a spare, Renaissance-red smock. A chain with absurdly large links trails from one of his shackled wrists. He is meant to be the slave on the emblem of the abolition society come to life and taking a moment of rest from his habitual pose, his gaze still turned in the direction of his petition. The smock opens in a deep V across his chest, revealing a wide and strangely flat expanse of brown skin, as though the artist made the decision to emphasize Aldridge’s body and skin color after the sitter had left the studio. The earthy brown and red palette of the Aldridge portrait connects the image to antiquity. To the modern eye, the slave’s smock also stretches forward in time to suggest orange prison scrubs, an allusion the artist could hardly have anticipated, but one that gives the portrait enduring resonance. The painting suggests that the captive slave’s status is classic, even biblical, static, and inherent in his corporal form. The pose of the sitter and the direction of his gaze put the viewer in the position of a voyeur, rather than an interlocutor.

In John Simpson’s The Captive Slave, the “pose of the sitter and the direction of his gaze put the viewer in the position of a voyeur.” (Art Institute of Chicago)

Aldridge may have approved of this painting, as useful propaganda in the cause he championed, or as a stunning testament to his emotive talent as a tragedian. Maybe he even called upon his experience as a dramatist to help direct his pose, costume, props, and expression. Nevertheless, it is striking that the best portrait of this fascinating man portrays him as a version of a two-dimensional image, giving little hint of his private self. Like many of the extraordinary and extraordinarily lucky Black people of his era, he used his success to promote what should have been obvious: the equal humanity of people of his complexion. But in spite of the personal independence he had achieved, in spite of his ability, from his privileged position, to advocate for his people, he was still constrained to issue these appeals in the stilted symbols his white audiences found most palatable.

On the same visit to the Art Institute, I renewed my acquaintance with Kehinde Wiley’s portrait of Barack Obama, here on loan from the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. I wanted to see again how Obama was officially memorialized—a man who achieved escape velocity from the clinging force of these inherited caricatures. Of course, he performed, as all public figures do, sometimes borrowing from Martin Luther King Jr., sometimes from the attitudes and turns-of-phrase of earlier presidents. But there is no inherited archetype, no script for a Black president. The portraits of Aldridge and Obama make an interesting pair. The deep V of Aldridge’s chest emphasizes corporality and suggests nakedness, while the shackles at his wrists remind the viewer of the tragic status slaves inherited with color. The message is that the slave has been doomed by his body. The same space on the Obama portrait is taken by the placket, collar, and cuffs of a crisp white shirt—Obama’s body is his own, unavailable to the viewer. Aldridge’s hands splay lax and exhausted across his thighs. Obama’s are crossed in front of his abdomen, communicating reserve. Obama’s direct and attentive gaze holds no hint of petition.

What is most interesting about the Obama portrait is how Wiley has conveyed his status. In American history, markers of status, public and domestic, have often served as painful demarcations, excuses to be human in only some settings or to reserve humane treatment only for some. Wiley has painted Obama in front of a chinoiserie wallpaper, like that of a well-appointed English or American drawing room of an earlier time, and sitting on a strangely proportioned chair that combines the ornamental styles of several eras. But this is no stilted invocation of these classic indicators of high class. The wallpaper is such a lush green that it sears the eyeballs, and Wiley has painted it coming to life, surging around Obama’s feet. Elements that appear in classic Western portraiture as markers of a sitter’s fixed place in the world, including décor, furniture, and a brown-skinned attendant, reappear here totally transformed. The wallpaper is alive, vibrant, playful. The furniture is invented, fanciful, floating. The Black man is really a man, not a prop: individual, specific, private.

As I said, for those of us who survive it, life among a people who objectify us, who make us play simple roles in a theater of their own triumphant story—it is a training ground. It teaches us to tell the difference between form and reality, between the demands of society and our private selves. We can’t help becoming keen to absurdities when society is so frequently absurd at our expense. A Black artist like Wiley, or for that matter Ira Aldridge, or Sojourner Truth, can introduce surprising juxtapositions among the well-worn aesthetic clichés they know so intimately. They can reveal that what was thought fixed is flexible; they can center on the canvas whomever they want. And this is really the problem of the moment, the issue pressed by the kneeling protesters in the summer of 2020, and that continues to unfold now in ferocious public debate about race and American history. Give us the stage for a moment and there is the risk that a well-rehearsed and comforting scene may turn playful, ironic, subversive—or even revolutionary.

In a photo taken at a protest in 2020, we see a kneeling man, lightly dressed for summer, urgently addressing a phalanx of armored police. The echo of the abolitionist’s seal is pointed, but with a difference. The kneeling figure is no longer alone. He is surrounded by a crowd carrying recording devices, every lens pointed in his direction, and he knows it. The kneeling is ostentatiously performative. By taking this pose, he is not just overleaping the riot shields of the police with a personal emotional appeal. He is also speaking to the cloud of witnesses surrounding him, and to us. His kneeling has become a martyrdom, not just the pathetic appeal of an unheard victim. It is a challenge to those who would deny his humanity, provoking not pity but shame. In the moment, his gesture may have made it more likely that the officers he spoke to would attend to him. But whether they listened or not, in all of the images of him holding this ancient pose in a new context, he has claimed an undeniable authorial power over the meaning of the scene.

It’s a moment that captures something important about our time. Following each of the successive murders that have so galvanized public conversation about race in American life in recent years, we have seen confident assertions by Black Americans to authority over how these stories should be told. The murders must be contextualized, Black Americans insist, as part of a narrative that includes 400 years of suffering innocence, beginning when the first Africans were brought against their will to these shores. And we are in the midst of a furious backlash about how to talk about American history, from those who insist that the past deserves reverence and that we must not emphasize its horrors.

The uncomplicated and wholesome version of the American story only works, of course, with a white narrator, one who minimizes or omits the perspectives of Americans for whom this description is laughable. In such stories, the white man strides the stage as the protagonist while disenfranchised women, Blacks, indigenous people, and others exist only as props supporting his triumphant refinement, over time, of honorable American principles like liberty and democracy. It is this very instinct on the part of white narrators to oversimplify and self-soothe that has dictated the view of Black people as two-dimensional and interchangeable. To be convincing, such narratives require that the exploitation Blacks have endured—indeed, that Black lives themselves—must matter less. They must not weigh so much in the balance that the loss of Black life begins to darken the tone or change the moral of the tale.

It is no wonder that in America, a Black author has always been greeted as a fearsome figure. This anxiety was the thrust of the attack on The New York Times’s 1619 Project and its lead author, Nikole Hannah-Jones. This is what motivated the 1776 Commission, the Trump administration’s anemic pamphlet response. And it underlies all the current hysteria over that much-abused term, critical race theory, including the waves of state legislation purporting to constrain schoolteachers to programs of patriotic education.

In general, we are in a time of retrenchment of old ways of thinking about race and power in American politics and society. Congress’s negotiations over voting rights are, at base, about whether Black populations in conservative states should be able to effectively share in governance, or else whether, in an echo of the Three-Fifths Compromise, Black populations should be counted to increase their states’ share of national power while Black people themselves remain powerless to shape policy. Those who find white supremacy convenient seem to be winning the fight to restrict access to the ballot, at least for now. But Black intellectual power is not susceptible to similar limitations.

Instead, a tide of talented journalists, historians, artists, directors, novelists, and poets—a Black Renaissance of stunning breadth—has risen to meet the urgency of our moment. The result has been the inexorable emergence of the Black narrator in American public life. In the face of this development, some seem to fear the relegation of the white American to an underdeveloped side character in the national story as we tell it, and in a role that is not always a flattering one. They fear being labeled racists, such a reductive term. They fear that they will be diminished, in effect, to a two-dimensional figure. In all this legislation and agitation over how American history must be taught, one hears a repeated, frantic cry to the effect of: “Narrator, turn your terrible gaze from me!” One marvels at this turnaround.

But it is just possible that we, who have suffered from it for so long, have no desire to undersell the humanity and complexity of others. Americans’ long insistence on seeing the Black man on his knees has exacted a terrible cost. I know I’m not alone in that I have only to close my eyes to see the photo negative of that image imprinted on my retina: Derek Chauvin kneeling on George Floyd’s neck until he died. The truth is that no one need be subordinated for new perspectives to add to the accounting of our national story, our national character. All that this moment requires of white Americans is the courage and humility to admit our full equality. Indeed, the common pose in our recent protests worked so well as moral reproach because it provoked reflection on what I hope is a shared intuition—that in a country like ours, no one should have to kneel.