On Visitors

When the Bachelor Girl and the Red Death come calling, are they mirrors for our eccentricities?

Oh, do not ask, “What is it?”

Let us go and make our visit.

—T. S. Eliot, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

This morning I looked out at the road across from my side yard, hoping to see the wild turkeys. My husband made a short video of them eating spilled birdseed below our bird feeder. There were once 17 of them. Seventeen! Then there were 15. Last year, early in the summer, I saw only one, pecking along the gravel path. Let’s be honest: I wondered what its life was like, without family. I did hope another turkey or two would pop up from behind a bush, or emerge from the high grass. Nada. And now I don’t even see him. It might have been female, I suppose, but in New England you have to hear about my gender all the time (called “she”) because of all the talk about boats. So, to me, the turkey—a non-boat if ever there was one—was male.

Not that I’m really so pathetic that I thought a wild turkey had come to visit me. But that didn’t diminish the pleasure I took in its existence, in its being part of my visual world. Seeing it was enough: all the imaginative scenarios it allowed me to conjure up (no; I wasn’t going to shoot it), all the connotations it invoked. To some extent, seeing can be better than having. I had no responsibility toward the turkey (can I even imagine that I might have seen the fox, and it wouldn’t?). I projected onto it many virtues. I felt at peace with my turkey.

Flannery O’Connor, in her essay “The King of Birds,” begins by discussing a visitor she once had:

When I was five, I had an experience that marked me for life. Pathé News sent a photographer from New York to Savannah to take a picture of a chicken of mine. This chicken, a buff Cochin Bantam, had the distinction of being able to walk either forward or backward. Her fame had spread through the press, and by the time she reached the attention of Pathé News, I suppose there was nowhere left for her to go—forward or backward. Shortly after that she died, as now seems fitting.

Ms. O’Connor can always be depended upon to be amusing, but what I see in the introduction to her fine essay now, as opposed to when I was in my 20s and first read it, is this: in a way, I have become the chicken. The human visitors to my house have come to observe. They can’t observe me if they’re emailing or texting. They want to see me walk either backward or forward, in effect. And the best place to do that is from the viewing gallery on the back porch, where I often take several steps backward before turning in the direction I’m headed, as I maintain eye contact while conversing with the visitors. Backing up has its advantages, and unlike the garbage truck, I don’t make a high-pitched beeping sound as I do it. In some cultures, this way of leaving would be courteous, a sign of deference. But of course I was thinking metaphorically: they want to see me walk backward and forward (might I be entertaining both Republicans and Democrats?), the same way they’d like me to jump through hoops. If you see what I mean.

I’ve written in these pages before about house guests, thereby offending my dearest friends and drawing to me others, who more easily assumed I had to be kidding. Let me be clear: I like visitors. I haven’t exactly struck up a fascinating social life in southern Maine. I hear that as you go north, people get friendlier. When the winters are bad, it behooves everyone to pull together: you dig out my back wheels, I’ll help you patch that hole where the flying squirrels got in. Such things pass for bonhomie around here. For downright merriment.

As summer approaches, I’ve been thinking about the concept of a visit. What does a visit mean, anymore, when we can text our innermost thoughts and when travel has become so exhaustingly terrible that people often won’t attempt it?

In the chapter “Hosts and Guests” in Amy Vanderbilt’s New Complete Book of Etiquette (1963), the subheadings are: “Who Invites Whom. Arrivals and Departures. When There Is No Host. Should a Guest Be Called For? The Extra Woman. Acting Host for a Bachelor Girl. How a Guest Takes Leave. Thank-you Notes.” The mind boggles. What would happen if you were inviting a Bachelor Girl to spend the weekend, and you found out she didn’t drive, so you sent your husband to the bus station to pick her up, and when she was leaving she told you that she wanted to be honest before taking her leave: your husband’s driving was frightening, and also, did you realize he mutters to himself? What would happen if the Bachelor Girl showed up and saw another set of guests leaving? (In my experience, having guests overlap is as much of a faux pas as letting a lover know you have other lovers.) Or let’s forget her for a minute: What if you invited Amy Vanderbilt and she found out she’d have to share the guest room with a Bachelor Girl, and then they jointly wrote you a thank-you note filled with exclamation points (in my book, the optimal punctuation mark of summer)? Would it be impolite to sell it on eBay?

The visitors come trailing not clouds of glory but bags of gourmet food sure to cause great confusion, whereas a dinner of baked chicken, rice, and carrots could confuse only the truly young (put carrot in eyes?) or truly old (is this dinner?). Should the expensive jar of minced shallots with pickled ginger and blood orange reduction be put on the table alongside the salt and pepper? Are you required to put on your reading glasses to make sure the label lists no euphemism for a preservative that might send someone in the family—such as Fluffy, if she jumps up onto the table when no one is looking—to the ER?

But let me get back to O’Connor’s essay. Time was when the visitor had a job. The visitor wasn’t casually visiting; he or she would have been sent on assignment. No doubt some iced tea or lemonade would change hands, but those visits were actually meant to accomplish something, so they had a double meaning. Now, such visits can happen on Skype, if anybody needs to look up my nostrils to see how I’m reacting to something. I, too, in this ambiguous new world, often wonder whether a visit is personal or professional, though even without my etiquette book, I’m sure that asking would be wrong. If someone comes to interview me, for example, I don’t confuse this with their desire to spend the night in the guest bedroom. This has happened, certainly. Of course I don’t want people to drink and drive, and I’m quite sensitive to budget cutbacks. A writer friend in California emailed recently to tell me she was expected to provide the wine for her reading/signing. Still, I’m joking; I can tell the difference between a social and a professional visit. When my doctor comes over on Halloween, bringing the medical students in the book discussion group, that is a social visit. Whatever he thinks about what I’m snacking on, he isn’t going to talk about my cholesterol problem. I’m being paid a visit. I’d be stunned if they all drank and passed out. They seemed alarmed enough that little people in skeleton costumes kept pounding on the door.

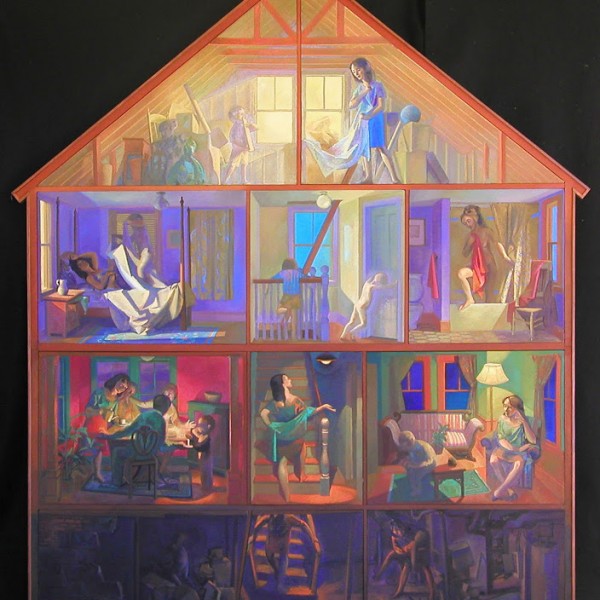

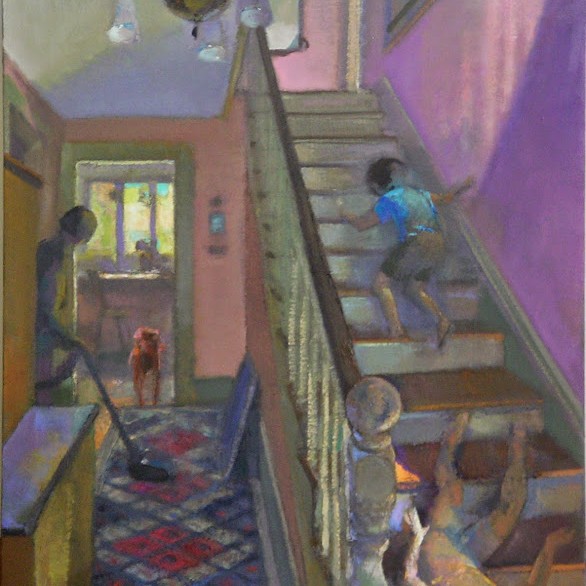

Let’s take another, slightly different, hypothetical case: one in which I am asked to visit. Now, this would hardly be the same as having Mark Knopfler stop by, in which case I’m sure he would at least know that they hoped he’d be moved to pick up his guitar. I can say honestly that almost anyone I know (except for Edmund White and Michael Carroll) would be dismayed if I pulled a new short story manuscript out of my apron pocket and started reading. Rule One of writer’s social etiquette is that writers never say or do anything—except when forced to, to promote their work—that indicates that they write. I, myself, often speak of “some things I’m typing.” My husband’s painting studio is on the third floor, which he refers to by saying that he is “going to the attic.”

Our odd prohibitions against speaking the truth aside, what does constitute a visit? Is it merely that some time is spent in someone else’s company? Are expensive gourmet items part of the deal? Can pajamas be mentioned early in the conversation? Is it necessary for the thoughtful visitor to insist that you go to the attic or that you type in order to make you feel that you are still free in your own house, which of course makes you feel even guiltier because you know you are, but you thought you were getting a time-out, a visit? Must visitors offer to take you out if they are coming for one night? Two? Are their jokes about expense accounts so unfunny that it would be like their talking about how Tyrannosaurus rex roared to them to have a nice time as they went running across the field?

[adblock-right-01]

And this important question: Can visitors bring visitors? Might that then turn into a situation best expressed by that old cliché that the enemy of my friend is my friend, or whatever the cliché is? More questions would be: If the visitor repeatedly compliments your washing machine, is he or she hinting? When you’re asked what time you usually get up, should you be honest and say that if the melatonin and the valerian capsules don’t work and you have to take Ambien, the answer is “around noon”? If the guest asks whether the electric toothbrush disturbs you, should you admit that it wouldn’t bother you, but Fluffy would be sure to get under the sofa and claw out all the cotton batting? Is the question “See any UFOs around here?” a joke, or a test you might fail? If the person asking you is an ophthalmologist, can you answer honestly that you have so many flashes in your peripheral vision warning of a retinal tear that you couldn’t possibly say? Should really, really disturbing gossip (“How many embryos were implanted? And the husband believes they’re his?”) be imparted just before bedtime?

Let me move on to a second literary point of departure: “The Masque of the Red Death,” by Edgar Allan Poe. (No, no, I’m not going to confuse the fact that he’s dead with his being about to walk into the room, as I did with Amy Vanderbilt.) In this story, you may remember, Prince Prospero, fearing the devastating plague sweeping through his country, retreats to the forerunner of a gated community (he has a castle, rather than a McMansion; he also owns whatever is inside), where the walls “had gates of iron.” (If this had been the Nixon White House, there would have been many men in elaborate uniforms to open them, but that’s neither here nor there.) There is a masked ball, during which time a figure costumed as the Red Death penetrates the fortress (similarly, the Red Death might have made an appearance at Truman Capote’s famous black and white ball, if on Capote’s A-list, and willing to dress appropriately for the occasion, and if this weren’t an anachronism). All the rooms are painted different colors, but in the black room, there are blood-red windows:

In the western or black chamber the effect of the fire-light that streamed upon the dark hangings through the blood-tinted panes was ghastly in the extreme, and produced so wild a look upon the countenances of those who entered, that there were few of the company bold enough to set foot within its precincts at all.

Nota bene: you may have clear ideas about home decorating from reading magazines such as Elle Decor, but it won’t do you much good when you’re dealing with the Red Death. The Red Death is not so much a visitor, though—I don’t want to give visitors a bad name—as an intruder (this could get us back to Truman Capote, and that nasty story he revealed in Answered Prayers, but I won’t digress). This intruder proceeds, with spots of blood on his costume (reminiscent of someone who has dribbled the shallot condiment, for example) … anyway, the prince feels this to be in bad taste, a mockery. The irate but courageous prince (who hates having his party ruined) stabs the already blood-flecked person dressed in black, who is then unmasked as the Red Death. All die. This is clearly a visitor at his worst. But let’s just tone this one down for a minute and imagine someone coming to visit whom you haven’t really invited. Let’s say they make gestures toward blending in (major costume for the ball; perhaps, in my lesser example, wearing jeans like everyone else), but they’re also a little too ironic or even the opposite of irony, they’re too forthright—but they’re just not for you. What is the etiquette? You’re obviously not going to stab the person, and no one comes to visit as the embodiment of anything (except inadvertently, as Flu Season), but still, what exactly should you do with such a visitor? It seems to me that yawning is always appropriate in such a situation, checking one’s watch (forgive me for leaving out the important clock in Poe’s story), even saying that it was nice to see them, while adding helpfully that there’s a Motel 6 up on the highway. Consider, also, installing a peephole, and practice being a New Yorker, tiptoeing to the door as quietly as the way the fog comes on little cat feet, to see the appropriately funhouse-mirror face of your ex, come to retrieve his books, or Girl Scouts with distended squirrel-in-winter cheeks.

One last mention of a literary visitor who really shakes things up: the blind man in Raymond Carver’s “Cathedral.” The blind man, Robert, is a friend of the man’s wife and comes to visit, but the story’s dynamic is primarily between the two men. The blind man eventually provokes an ability to imagine in our main character, and the host does become more enthusiastic and more interested in the evening. What is a cathedral? Both seem to end up fulfilled, at story’s end, in their various, odd ways, even though we continue to squirm (if the comatose wife ever wakes up, what then?). This is a much too quick paraphrase and does not begin to describe this weirder-than-life-because-it-is-life story. Here is a particularly brilliant passage, greatly understated, yet meant to link the subtext of the story, with Carver intentionally conflating the wife with the blind man, as well as with her husband, as well as with their unstated desires and assumptions. The blind man suggests that in order to better understand what a cathedral is, he and the husband draw it. The way he expresses it, though, is this: “ ‘All right,’ he said. ‘All right, let’s do her.’ ” So! The sexual jargon (“do her”) is conflated with the process, and with the drawing that will emerge. In the reader’s mind, the wife has been made synonymous with a cathedral (as in: “cathedral of the body”). So when the blind man says, “We’re drawing a cathedral. Me and him are working on it. Press hard,” we can’t fail to understand the deeper, sexual connotations of the words. Soon afterward, the blind man’s encouragement continues: “Sure. You got it, bub. I can tell. You didn’t think you could. But you can, can’t you? You’re cooking with gas now. You know what I’m saying?” Yes, we do know what he’s saying. Although he’s an invited guest, he’s almost as insidious as the Red Death, because what is drawn, what is known, can never be erased or unknown, so that—as with many of Carver’s characters—they are fated to go on knowing so clearly what they don’t know that the nonverbal awareness becomes another form of torturous consciousness.

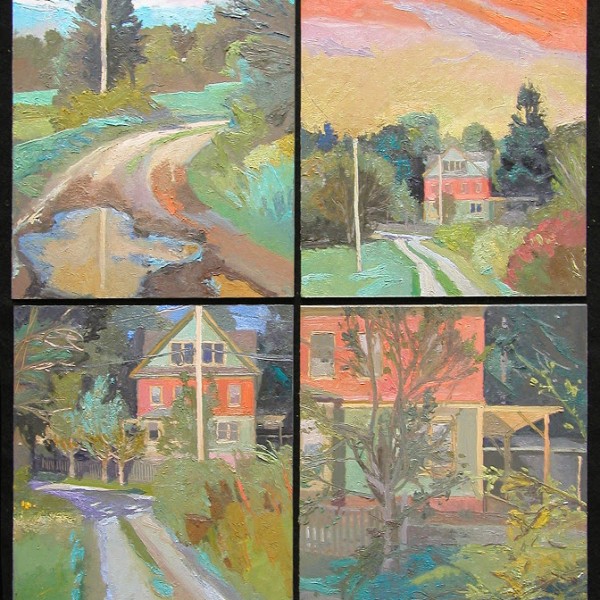

In my house, mostly maps are drawn. Nobody wants to envision Chartres; they want to know the best route to take to get the ferry to Monhegan. And that’s when the sad truth has to be explained: you have to go up, up, up the coast to get where you want to go, and the roads narrow and there are no passing lanes. If you get behind a logging truck, or even an SUV driven by somebody who’s stoned, the ride up the coast can be a very long ride. Years ago, visitors—mostly from Japan—would stop by, en route to the home of May Sarton. I never met May Sarton, but I knew her by sight and avoided her in the grocery store, she was so contentious. People were scared of her. She wrote about some of the locals with blazing indictment in her journals. Behind her back, people told stories at their own expense about how they’d dodged the May Sarton bullet: “Oh, you need a specialist, not somebody like me …” Many times, my husband, with an expression for visitors that was meant to be expressionless, got out the highlight pen and drew the best route between our house and hers. She had visitors, this being Maine; they sometimes stopped by to meet the Plan B writer (me), en route to Ms. Sarton. How she dealt with the many visitors, I don’t know, but I can attest that many came in pilgrimage, many scholars and admirers, many feminists, many curious people. To be visited by a curious person, I think, is much harder than being visited by someone who knows you well, who knows what to expect, who has already inevitably been let down by you (Gawd! You’re like Sunny von Bülow, you don’t get up until noon!).

I think of the visitors in Dickens. Jane Austen. Edward Gorey. Of the visitors in Joyce’s “The Dead,” which seems to me the ultimate Grand Guignol of visitor stories, becoming increasingly more claustrophobic, more tense, than we could have imagined. There are the invited (Mr. D’Arcy, the tenor) and the taken-for-granted (Lily, the servant girl). It’s a routine holiday, which assures anyone sensitized even slightly to literature that this is going to be an aberration, a downer worse than we could have imagined. Which it certainly is. Yes, possibly—possibly—Gabriel comes out the other side, after his awakening to the realities of his life, but he’s going to have to return to his aunt’s house, the celebrations aren’t going to stop just because he’s brought up short, he’s going to be in the same place, at the same time, next year—and this isn’t even a bad Broadway play. He’s in one of the rings of hell, as I read it. That famous epiphanic moment is gorgeous, but in terms of the future, his future on planet Earth, in Ireland, at the Misses Morkan’s house for the next holiday? I don’t even need to bother answering my question.

Here’s a thought: Might we sometimes invite visitors to trap us? To see us not as multidimensional, but merely at our worst (“Look what the damned dog did!”). If so, if we’re not just opening the door to the equivalent of a stranger who’s here to attend a “masked ball” in which everyone is mysterious, though protected somewhat by their “costume,” what might be the best result, the most ideal conclusion, about admitting a visitor to our home? Charitably, I have to mention that we might come to know them better and that the same might be said about their awareness of us. A visit might just be a social form, a way of extending oneself, and what’s wrong with that (especially if you aren’t haunted by visits in literature)? It makes us look better in our own eyes. Think of the Bachelor Girl. Would you want to be her? (For the sake of argument, don’t all raise your hands at once.) Picking up Ms. Vanderbilt’s etiquette book from the early 1960s, now so outdated as to be hilarious (Where is Susan Sontag, where is camp, now that we need it?), I read that,

If he [the helpful male host] does seem very much an intimate of the household … there is, possibly, some speculation concerning his exact relationship to the hostess. To allay such speculation, a bachelor girl may designate more than one “acting host” from among her men friends. But if only one serves, he is careful to leave with the last guest if it is late in the evening. Even if the relationship between “host” and hostess is quite intimate, a gentleman must always go to elaborate lengths to avoid anything that might appear to be compromising. Even an announced engagement doesn’t free him of this obligation.

While I am still gasping, let me say just a few things: first, the idea of getting my husband, let alone a group of “men friends,” behaving as “acting hosts” would prove me delusional. I know, I know, I’m married, and it’s not the same as being a Bachelor Girl, but sometimes when I’m running around, doing everything as the hostess, it feels like I’m Bachelor Girl Run Amok. Also, my husband does often leave with the guests—at least long enough to shine a flashlight in the dark, so they don’t fall off the one sneaky step at the end of the walkway. Years ago he also aimed the light into our garage for our permanent summer guest, about whom my friend Dadée—who was exiting at the same time as the Permanent Guest—said to her husband, “George! I think he lives in their garage!” I have to admit that my husband also runs out of the house in order to plunge something into the garbage can—lobster carcasses, or tins of anchovies dripping oil. On these occasions, sometimes an animal gets his attention (please let it not be a skunk), or he notices the stars. I have sometimes been summoned to see whatever it is he has seen in the absence of our guests: the full moon; the damned swamp maple turning red in early September; the reappearance near our fence of dreaded bittersweet; the huge nest of bees in the ground that he blasted three times with poison that can be squirted from 25 feet. (Of course he did not tell me about this until he had done it. Three times. My husband is wildly allergic to bee stings.)

[adblock-left-01]

What could we possibly be without visitors? They become the mirror for all our eccentricities and all our insufficiencies. Every visitor has so many things about which she is both enlightened and informed and blind. As do we. Yes, we are surprised sometimes to see the left-behind medicine bottle in the bathroom, as they have no doubt been scandalized to see that the floating duck in the bathtub grew mold on its underside and, furthermore, neither of their hosts has sold anything in months. What can you do but bring on the champagne (though only in a manner of speaking: last summer we liked a Spanish sparkling wine, Cristalino, we got for $7.29 a bottle, discounted by the case).

I’ve omitted mention of the heated discussions about politics, underneath the strands of pig lights glowing at the perimeter of the back porch that make it seem we’re on a ship at sea (the S.S. Porcine? ), or some party we’re simultaneously having, and nostalgic for, out of Marjorie Morningstar. My feeling is, if you’re going to be visited, don’t sit there and just take it, like a Carver character; be expansive and deflect attention as much as possible from painful talk—since how can it be anything other, in this Year of Ukraine? If someone comes to stay, whatever they bring with them gets into play: libertarianism; pajama bottoms big enough to hide a dog inside each leg; the manuscript they’ve been working on for the past six years.

The departed authors of the essays and short stories I’ve mentioned can now have the last word on this subject—they are my guiding lights—and here’s what I imagine they might say: Flannery O’Connor might say that she died way too young, but that her visits to Sally and Robert Fitzgerald opened another world to her. Carver? Visitors often embodied the subtext, or perhaps the subconscious, of his stories. He certainly died too soon, also, though he wrote a very plaintive poem called “Gravy” about the many blessings he felt he’d had, so the rest was just gravy. Poe? Well, he didn’t last that long, either. He might say that the mysterious annual visitor to his grave in Baltimore was much appreciated, because who couldn’t do with a flower and a bottle of booze?

This leaves only Amy Vanderbilt, who once thought so many things could be explained. Such clarification has all gone up in pixels and been done in by technology and its graceless protocols, by the various rings of cell phones that we’ve selected as the soundtrack to our lives. By 24-hour news, and the illusion we’re constantly in touch. We are, in reality, out of touch.

Give me my porch, my husband walking around barefoot, my friends, the summer visitors on their way somewhere else that holds so much promise for being simple: no cars allowed on Vinalhaven; so few ferries to Monhegan; bad cell phone reception; unreliable Internet. We vote with our feet. The summer visitors all become the chicken that wants to walk backward as much as it wants to walk forward.