The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America by Frances FitzGerald; Simon & Schuster, 752 pp., $35

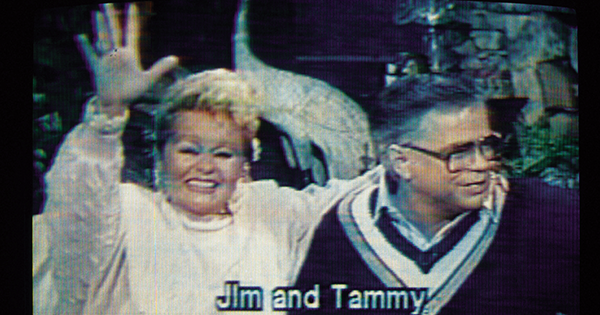

While reading Frances FitzGerald’s new book, The Evangelicals, I remembered a summer night in Alabama when my wife and I stopped by my parents’ house for a visit. Dad was standing in front of the TV struggling with the channel selector, a new gadget he had yet to master. On the screen, Tammy Faye Bakker’s mascara was running down her cheeks while her husband, Jim, was trying to squeeze money out of poor Southern whites like us.

Dad didn’t have any use for the Bakkers. “What do they have to cry about?” he’d ask. Hadn’t the Bakkers run into a rich boy named Pat Robertson, a Virginia senator’s son who had failed his bar exam but had enough money to buy a TV station and hire the Bakkers to host a children’s show? Robertson even let Jim Bakker co-host The 700 Club. When all the crying and carrying on brought in more money than either Robertson or the Bakkers could have imagined, Jim and Tammy Faye broke off to start their own network, PTL, and then built a Christian-themed amusement park in South Carolina that became the third-most-visited amusement park in the country in the 1980s.

But my father thought their ending was a hard one. On a tip from Jimmy Swaggart, a fellow evangel-ist and philanderer, Jim was exposed as having an affair with his secretary, to whom he had been paying hush money. He was also accused of participating in “mutual masturbation” with male members of his staff and was convicted of stealing from the ministry’s contributors in a Ponzi scheme. When he finally got out of prison, he admitted that before he went in, he had never even read the Bible in full.

FitzGerald, best known for her classic 1972 book about Vietnam, Fire in the Lake, mentions these details, along with brief asides about preachers like William Branham, who claimed to have raised people from the dead and believed that Eve had “mated with the snake” before giving birth to Cain. But FitzGerald’s purpose is much more than anecdotal: over the course of more than 700 pages, she gives the full, authoritative history of American evangelicalism, the spreading of the “good news” that humans were not “utterly depraved” and had not already been elected to be saved or damned, no matter what they had done during their earthly lives.

FitzGerald writes that Jonathan Edwards, the son of Congregationalists, had first parroted the standard Puritan fare but had also incorporated the notion of “free will,” and after what he described as a “sudden, surprising descent of the Holy Spirit,” began preaching that man could have a “direct relationship with Christ.” The idea launched the First Great Awakening in 18th-century America and was spread throughout the colonies with the help of an itinerant English evangelist named George Whitefield. After the Revolutionary War, the Second Great Awakening peaked in 1801, when thousands of poor Scotch-Irish settlers, the People of the New Light, descended on Cane Ridge, Tennessee, and fell into ecstatic fits of shouting, singing, and rolling on the ground as they experienced the joy of “free grace.”

For a 19th-century premillennialist preacher like William Miller, the purpose of a personal salvation experience was to usher in Christ’s return to earth, which he predicted would take place in 1844 if only enough of his listeners would sell their property and huddle together on a mountaintop to await their Savior. Meanwhile, another influential revivalist named Charles Finney thought that the good news would result in the creation of a “new heart” and might serve an additional, wider purpose, such as ending slavery or recognizing that women were equal to men, stirrings of what Washington Gladden would later preach as the Social Gospel.

FitzGerald argues that this dual nature of evangelicalism, compounded by the descent into civil war, split the Methodist, Baptist, and other denominations into an ever-widening divide between fundamentalism, the most doctrinaire and backward-looking form of evangelicalism, and modernism, its opposite. This rift involved more than splitting hairs over the exact number of days until the Rapture. Not only did the debate call into question the central miracles of the Bible (the Virgin Birth, the resurrection of the body, and so forth), but it also extended to the question of “whether God had ever intervened directly in human affairs,” thus challenging the truth of the Bible in its entirety.

These arguments, some of them later incited by the sudden economic dislocation at the turn of the 20th century—rural to urban, farm to factory—eased in time for the antagonists to applaud America’s entry into the First World War in 1917, but the consensus fractured again when the horrors of that war became manifest. In its aftermath, and during the continuing migration of the poor and marginalized from the mountains to the godless cities, the stage was set for the single greatest battle between the fundamentalists and the modernists: the Scopes trial, in which fundamentalist William Jennings Bryan lost to Clarence Darrow. Nevertheless, FitzGerald writes that to this day “perhaps one half of evangelicals continue to reject Darwinism.”

FitzGerald is sure-footed when she chronicles the rise of evangelists like Billy Sunday, Oral Roberts, and of course Billy Graham, whose steadiness and civility would make him the most admired minister of the 20th century. But the heart of The Evangelicals begins in Lynchburg, Virginia, home to Jerry Falwell and birthplace of the Moral Majority. Here FitzGerald’s prose comes to life in a way that can only be achieved by a writer who has gone to the actual place, talked to its residents, and kept an eye out for detail and an ear tuned to the rhythms of ordinary speech. She recounts how Falwell once told the many thousands of his congregants that “to read anything but the Bible and certain prescribed works of interpretation was at best a waste of time.” He railed against “secular humanism,” and polls indicated that “over a third of Americans described themselves as ‘born again’ ” and that “an additional third … agreed that the Bible [was] the actual word of God to be taken literally, word for word.”

The mid-1970s seemed ripe for the emergence of a politically powerful coalition of “fundamentalists, Pentecostals, Southern Baptists, and other evangelicals.” FitzGerald tells us that national figures like Pat Robertson and the Bakkers appeared poised to lead it, but for different reasons held back. That left Falwell at the helm, along with Equal Rights Amendment opponent Phyllis Schlafly, who joined him in the fight against secular humanism, asserting that it would lead to sex textbooks in public schools, unisex toilets, and the legalization of homosexual marriage.

The movement gathered steam, eventually coalescing around two major issues: abortion and gay rights. After Ronald Reagan defeated Jimmy Carter in 1980, optimism was high. For the first time, thanks in large part to Falwell, FitzGerald says, the “fundamentalist sense of perpetual crisis, and of war between the forces of good and evil” had been “introduced … into national politics.”

The Evangelicals concludes with a riveting chronicle of the swift decline of the Moral Majority and the rise in its place of a politicized Christian right, which gave its full weight to the fight against abortion and gay rights, particularly gay marriage. It went on to lose the unnecessarily protracted fight about Terri Schiavo’s feeding tube. It could not, or would not, sufficiently condemn the murder of doctors who performed legal abortions or the bombing of abortion clinics, such as the one in Birmingham, Alabama, that killed an off-duty policeman and terribly injured a nurse. It ignored looming environmental catastrophes like global warming. It opposed, or didn’t fight for, national health insurance, and it did not, with the exception of pastors in the mold of Rick Warren, take much of an interest in the plight of the hungry, sick, and homeless around the world.

Instead, the Christian right’s Machiavellian, twilight struggle—largely carried out by political hacks—was doomed to fail because of one unassailable factor: demographics. The millennial generation is the least-churched and most diverse in American history, and on the whole, is passionate about extending rights to gays, lesbians, transgender people, and other groups of their fellow citizens who have been the objects of discrimination and hate. Even the Southern Baptist Convention has distanced itself from the Christian right, which had been co-opted by the Tea Party, a more sinister movement that appeared not to be in any way religious.

I heard the other day on NPR that an estimated 80 percent of the white evangelical vote went to Donald Trump. FitzGerald’s brilliant book could not have been more timely, more well-researched, more well-written, or more necessary.