Orwell’s Last Neighborhood

While envisioning the darkest of futures and grappling with mortality, the English writer retreated to an idyllic Scottish isle to write Nineteen Eighty-Four

It’s hard to know what would be a good place from which to imagine a future of bad smells and no privacy, deceit and propaganda, poverty and torture. Does a writer need to live in misery and ugliness to conjure up a dystopia?

Apparently not.

We’d been walking more than an hour. The road was two tracks of pebbled dirt separated by a strip of grass. The land was treeless as prairie, with wildflowers and the seedless tops of last year’s grass smudging the new growth.

We rounded a curve and looked down a hillside to the sea. A half mile in the distance, far back from the water, was a white house with three dormer windows. Behind it, a stone wall cut a diagonal to the water like a seam stitching mismatched pieces of green velvet. Far to the right, a boat moved along the shore, its sail as bright as the house.

This was where George Orwell wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four. The house, called Barnhill, sits near the northern end of Jura, an island off Scotland’s west coast in the Inner Hebrides. It was June 2, sunny, short-sleeve warm, with the midges barely out, and couldn’t have been more beautiful.

Orwell lived here for parts of the last three years of his life. He left periodically (mostly in the winter) to do journalism in London and, for seven months in 1947 and 1948, to undergo treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis. Although he rented Barnhill and didn’t own it, he put in fruit trees and a garden, built a chicken house, bought a truck and a boat, and invested numberless hours of labor in what he believed would be his permanent home. When he left it for the last time, in January 1949, he never again lived outside a sanatorium or hospital.

I came to Jura after a two-week backpacking trip across Scotland. My purpose was to drink single-malt on Islay, the island to the south, and enjoy two nights of indulgence at Ardlussa House, where Orwell’s landlord had lived. I was not on a literary pilgrimage. Barnhill is not open to the public, and no one among the island’s 235 residents remembers Orwell.

Nevertheless, it’s hard not to think of him here. With a little work, you can almost retrace his steps, day by day. Orwell kept a diary from at least 1931 until October 1949, four months before his death. In his introduction to a 2012 edition of the diaries, the late Christopher Hitchens—Orwell’s biggest contemporary champion—wrote that they “enrich our understanding of how Orwell transmuted the raw material of everyday experience into some of his best-known novels and polemics.”

The entries from Jura, however, are an exception. They offer no look into Orwell’s mood, thoughts on politics, or difficulties with his novel. The only hint that he might be a writer is the entry of August 31, 1947: “Most of afternoon trying to mend typewriter.” Instead, the diaries are an account of seedlings planted, eggs collected, fish caught, and gasoline lost from a leaky tank; of the depredations of birds, rabbits, deer, and slugs on the garden; Orwell’s walks, his guests, and their outings.

The conventional wisdom is that Orwell’s years on Jura killed him, nearly robbing the world of Nineteen Eighty-Four. None of his biographers or friends seemed to consider that Jura, despite or because of its harshness, might have extended his life and given him the psychic space to imagine a place utterly unlike it.

Today, the island is just as empty, and life only a little less difficult, than when he was there. The 21st century has moved closer to Nineteen Eighty-Four than it has to Jura.

George Orwell didn’t like the Scots and was embarrassed that his real name—Eric Blair—led some people to believe he was one. Nevertheless, he’d had the idea of moving to a Hebridean Island for at least five years before he set foot on Jura in September 1945.

The place had been recommended to him by David Astor, an editor at a London newspaper, The Observer, for which Orwell wrote book reviews. Astor’s family, wealthy as few others, had a summer estate on the island. He arranged for Orwell to stay with a farm family. While there, the writer made plans to rent a vacant house near the northern end of the island the following year. “I was horrified when I heard this,” Astor later said.

Orwell wouldn’t seem the best candidate for life there. He was tired from work as a broadcaster at the BBC, a war correspondent in France, and a member of the Home Guard during World War II. He had a chronic form of tuberculosis and in a few months would suffer a pulmonary hemorrhage. His wife had died in surgery earlier in the year, and at the age of 42, he was raising their son, a year and a half old, with the help of a housekeeper.

At the same time, Orwell was famous for his love of adversity. Destitute, he had worked as a dishwasher in Paris, almost dying there in a paupers’ hospital, and had fought in the Spanish Civil War. Less known to his admiring readers was his fondness for gardening, cabinetmaking, and rural life.

The house he rented was situated on the 20,000-acre Ardlussa estate, which comprised the northern end of the island. The estate was owned by Robin Fletcher and his wife, Margaret, who had moved there after the war and were trying to restore its economic viability. They were happy to have another tenant even if he wasn’t a farmer.

Robin had been a housemaster at Eton, the boarding school Orwell had attended. During the war, he served in the Gordon Highlanders, was taken prisoner in Singapore, and had worked on the infamous Burma-Siam Railway. Margaret received three postcards of 12 words each during his three-year captivity. Her two brothers died during the war. One, a worker in a Glasgow aircraft factory, had collapsed mysteriously at 22; the other, Ardlussa’s previous owner, was killed in Belgium.

Indeed, the war’s human toll was everywhere in evidence. Among the estate’s tenants were two men who landed at Normandy, two veterans of the Italian campaign, and two former prisoners of the Japanese. Near Barnhill lived a single man, Bill Dunn, with a below-the-knee amputation from a war wound. He’d placed an advertisement in the Oban Times seeking a farm tenancy that Robin had answered. In a nearby croft was a former Polish soldier, Tony Rozga, who was married to a Scottish woman.

Orwell escaped injury in the war but had been wounded in its rehearsal. In 1937, he took a sniper’s bullet to the neck in the Spanish Civil War. Miraculously, its only permanent effect was on his voice, which people reported was high and soft. (Curiously, despite Orwell’s long employment at the BBC, no recording of him is known to exist.)

Jura had one store, one telephone, and one physician, at a village called Craighouse, 16 ½ miles south of Ardlussa House. Mail was delivered to the settlement there three times a week and forwarded to Barnhill, seven miles farther north, each Thursday. Food and fuel rationing was still in effect. The store in Craighouse kept the ration books, and island residents put in their orders by mail.

Orwell spent one night at Ardlussa House after a 48-hour trip from London. Interviewed decades later, Margaret Fletcher remembers that “he arrived at the front door looking very thin and gaunt and worn … a very sick-looking man.” The next day, she and Robin took him up to Barnhill and left him in the cold, empty, four-bedroom house.

Orwell got to work.

On May 24, 1946, in his second diary entry on Jura, he wrote: “Started digging garden, ie. breaking in the turf. Back-breaking work. Soil not only as dry as a bone, but very stony. Nevertheless there was a little rain last night. As soon as I have a fair patch dug, shall stick in salad vegetables.”

A few days later, his sister, Avril, five years younger, arrived. She’d spent the war as a factory worker and was ready for a long vacation. She, too, decided to stay for good.

Many people, both friends and biographers, have speculated about why Orwell decided to move to Jura. (He never addressed the question.) Among their theories: He sought a place lacking distraction. He was pessimistic about the world’s ability to avoid nuclear war and thought that a Hebridean island would be far from first-strike targets. He wanted to raise his son where the boy could run around outdoors. He feared Soviet agents might try to kill him as they had Trotsky, another of Stalin’s sworn enemies. (Orwell always kept a loaded Luger close by.) The magazine editor Richard Rees saw self-punishment in the choice. “I fear that the near-impossibility of making a tolerably comfortable life there was a positive inducement to Orwell,” he wrote.

Barnhill, looking much as it did in the late 1940s. Despite his failing health, Orwell landscaped it with a touchingly optimistic view of his life expectancy. (Alamy)

The current laird of the Ardlussa estate is Andrew Fletcher, the grandson of Orwell’s landlords. He’s 47, lean, and not afraid to wear pink running shoes around the house.

He and his wife, Claire, moved to Jura from Glasgow in 2007. He’d been a landscape gardener and she a programmer at a radio station; together they have four daughters.

Ardlussa House is a cream-colored, vaguely Georgian structure with a forest of chimney pots on the roof. (Parts of the building are older, dating from the 1600s.) The front hall is what you might expect from a Scottish estate house—the resting place of dozens of rubber boots and waxed cotton coats, houndstooth hats and canvas field bags hanging on hooks, and a bouquet of fishing rods sticking out of a bin.

Inside the big front doors is a bookcase filled with bound volumes of agriculture and estate management periodicals from another century, as well as single tomes, such as The Grouse in Health and Disease (Popular Edition), and The Red Deer of Langwell and Braemore by the Duke of Portland KG. Farther in is a relief map of the estate in a glass case, two shelves of Orwell literature, and a tray holding an opened bottle of single-malt. Upstairs are rooms off little corridors that seem not to connect to other parts of the house. Orwell spent several days here in late 1947, when his health worsened and a physician was called from Glasgow to consult. But there’s no plaque denoting his room.

Indeed, there’s little Orwell memorabilia on Jura. Barnhill, owned by Andrew’s aunt and uncle, has a stained claw-foot bathtub used by Orwell. The writer’s motorbike was junked more than a decade ago because, as Andrew recalled his uncle saying, “It was damaged beyond repair.”

Like Andrew’s paternal grandparents, Andrew and Claire are trying to reinvent Ardlussa as a sustainable business. Hunting (“stalking” in local parlance) and a small hydroelectric plant (“hydro scheme”) are the main sources of income. The estate also gets a conservation subsidy as a “site of special scientific interest” (mostly because of its mosses and lichens) and an agricultural subsidy for 65 head of cattle.

The land supports about 1,000 red deer, a large elk-like species, and hunters take about 130 a year. Ardlussa charges £600 to hunt stags and £400 to hunt hinds, or females. The estate keeps the meat, with the best cuts sold to London restaurants, the rest to supermarkets. Clients can keep the heads, although getting them home may be difficult.

My companion, Judy, and I stayed in a room on the second floor of Ardlussa House. We were there a half-year off hunting season, and we didn’t see a single deer. Jura’s latitude is above that of the Aleutian Islands, and the days were Arctic-long. It was sunny and warm, but not so warm that a fire in the hearth wasn’t welcome as we dined on the estate’s venison and salmon. Quilted window coverings blotted out the sun, which remained up until 10 P.M. We were there for the best part of the year—the wintry nights of June. When we woke early the next morning, we looked out one window and saw a red-haired girl leading a pony. Out another, her red-haired sister was herding ducks.

There are concessions to the isolation, however.

In 2016, Claire Fletcher and two other women opened a one-pot distillery called Lussa Gin. They make gin from grain alcohol flavored with 15 botanicals that they gather or grow on the island. They’ve sold more than 15,000 bottles, and the enterprise has made living in the middle of nowhere more interesting.

To stay in a place so isolated, you must have a sense of destiny. Or so believes Alicia MacInnes, a 40-year-old Australian transplant and one of Lussa Gin’s partners. She remembers the evening when she arrived long ago. “It was absolutely pelting rain. The woman picking me up, from the Jura Hotel, had backed the car down to the ferry. The boot was up. I could see her smiling face,” she told us one evening. After a pause, she switched to the second person, as if she were describing someone no longer herself. “You’ve been on a long journey. The car’s warm. Soon you’re traveling along single-track roads, exactly where you wanted to be.”

Her memory might be called Orwellian, in a pre-Nineteen Eighty-Four sense of the word.

The road from Ardlussa House to Barnhill is seven miles. The last three were what Susan Watson, the young woman who’d been Orwell’s housekeeper and nanny to his son in London, called “impassable to normal traffic.” Orwell walked the track many times. A few weeks after moving in, he returned to England to retrieve his son and Susan. When they returned, they hiked the last three miles, Orwell carrying Richard on his shoulders.

You can now drive to a dirt parking lot four miles from Barnhill and seven miles from Corryvreckan, the headland overlooking Scarba, the next island to the north. Both are worth the walk. Below Corryvreckan, in the strait dividing the two islands, is a whirlpool—the second biggest in Europe and the third biggest in the world. It is as much a tourist attraction on Jura as anything related to Orwell. Judy and I set out to have a look, too, but decided to stop at Barnhill along the way.

We parked the car, headed up the road, and soon came to a padlocked gate. It wasn’t attached to a fence, but with ditches on each side, there was no need for one. You can’t go off-road in Jura in a car. Even on foot it’s a slog, given the exuberant grass and ferns. Orwell, however, enjoyed bushwhacking. In June 1946, two weeks after moving to Jura, he walked across his end of the island, a round trip of 10 miles. At that point in his life, he had an eye for menace, and I wonder what he thought about a relic he found on the far side. “Old human skull, with some other bones, lying on beach at Glengarrisdale,” he noted in his diary. “Said to be survivor from massacre of the McCleans by the Campbells, & probably at any rate 200 years old. Two teeth (back) still in it. Quite undecayed.”

The ruts were as hard as concrete, with a strip of grass between them. Had Orwell trod here? It seemed unlikely the road had been moved. The pebbles underfoot might also have tormented his motorbike, his preferred mode of travel when it wasn’t broken down. His neighbors said he sometimes strapped a scythe to the rear seat in case he had to cut the track’s grassy middle. It must have been a sight—the cadaverous Orwell as the Grim Reaper assigned to a rural route.

The road rose and fell along a low ridge. Barnhill came into view at the end of a spur road that ran through a sea of ferns and cottongrass. Stone barns sat on either side. You can’t approach the house without opening a fence, guarded by a blooming foxglove.

Although Barnhill is available for vacation rental, starting at £1,000 per week, we saw no people. As in Orwell’s tenancy, it has a coal-fired stove, now supplemented with electricity from a generator, and it has a gas refrigerator. Online reviews and pictures suggest it’s still damp and shabby.

A connoisseur of discomfort, Orwell never planned to leave. He landscaped Barnhill as if he owned it, and with a touchingly optimistic view of his life expectancy. In his first weeks, he planted a garden with lettuce, radishes, onions, watercress, spinach, turnips, and seven types of flowers. The next month, he ordered four dozen strawberry plants, two dozen raspberry bushes, a dozen black currant, red currant, and gooseberry bushes, a dozen rhubarb plants, and a half dozen apple trees. On January 4, 1947, he planted “1 doz fruit trees” and more currants, gooseberries, rhubarb, and roses. On September 19, 1948—three months before he left Jura to enter a sanatorium in England—he planted peonies and pruned the raspberries.

One renter said it was a 20-minute walk from the house to the water, but you wouldn’t guess that from Orwell’s diaries. He and his sister, and later Bill Dunn, the amputee farmer who married her in 1951, spent a lot of time fishing. Some of their hauls were gluttonous (31 fish one evening in 1947). In his entry from August 18, 1946, Orwell described the method of preserving pollock, the usual catch.

Gut them, cut their heads off, then pack them in layers in rough salt, a layer of salt & a layer of fish, & so on. Leave for several days, then in dry sunny weather, take them out & hang them on a line in pairs by their tails until thoroughly dry. After this they can be hung up indoors & will keep for months.

We imagined Orwell digging in the garden and hanging his fish out to dry. Then we headed back to the main track.

Eventually we reached the settlement of Kinuachdrachd, to which Orwell regularly came to get milk for his son before he secured his own cow at Barnhill. Here, the road ended. A sign lying on the ground pointed us up a trail. “Gulf of Corryvreckan

2 miles,” it read. As we walked up the hill, we saw beyond the last house a rocky cove of Caribbean color and clarity. Climbing higher, we could make out the incoming tide’s chaotic embroidery on the water, and soon we could hear the maelstrom itself, a distant sound of water running over pebbles.

The hillside was covered in bright green cottongrass, horsetail, and sphagnum, with dark patches of heather. At the top, we looked to our right and got an aerial view of the Sound of Jura. Rocky, flat-top islands looked like a fleet of battleships at anchor. Beyond them was the mainland, furrowed by fjordlike “sea lochs.” Our position afforded a spectacular view of Scarba, which hasn’t had permanent residents since the 1960s. Birds glided in long arcs below us. We took off our shoes and ate our Ardlussa-packed lunches.

Two miles long, three-quarters of a mile at its narrowest, and with a tidal current that can reach 10 miles per hour, the Gulf of Corryvreckan is some of the most dangerous water in the United Kingdom. The speed and turbulence are partly due to the strait’s irregular depth. It is less than 350 feet deep in most places but has a 640-foot trench and a buttress reaching to just 90 feet below the surface at the Atlantic end. Wildly deflected water creates the whirlpool—sometimes a picture-book vortex, but more often a patch of standing or breaking waves. Even on windless days, there’s whitewater. Corryvreckan is a corruption of a Gaelic phrase meaning “cauldron of speckled water.”

But the most remarkable thing we saw wasn’t the whirlpool; it was the rest of the stream. As it rises to the surface, the deeper turbulence formed areas that resembled giant thumbprints or amoebas, which floated past us out to sea.

Soon, two Zodiacs appeared. About a dozen passengers in yellow helmets and orange life jackets sat on benches, like snapped-in Lego people. The boats came and went, playing tag with the edge of the rough water. After 15 minutes, they disappeared around the Atlantic side of Scarba.

“That may have been the show,” Judy said.

Ours was just as good. But Orwell’s was better than anybody’s.

In the middle of August 1947, two of Orwell’s nieces and one nephew—the children of his deceased older sister, Marjorie—came to Barnhill for a vacation. Orwell took them, his son, Ricky, now three years old, and his sister, Avril, to the Atlantic side of Jura on a camping trip. They stayed several days in an abandoned cottage. When it came time to go home, Avril and one of the nieces, who’d been spooked by the boat ride over, chose to walk back. “Uncle Eric” (as they called him) and the three others returned in the dinghy, powered by an outboard motor.

Orwell, however, had misread the tide table. They entered the gulf halfway between high and low tide, when the current was fastest.

“Before we had a chance to turn, we went straight into the minor whirlpools and lost control,” Henry Dakin, who was about 20 and on leave from the army, recalled years later. “Eric was at the tiller, the boat went all over the place, pitching and tossing, very frightening being thrown from one small whirlpool to another.” The chop bucked the outboard off the transom. It went into the water, and to the bottom. Nobody was wearing a life jacket. “Eric said, ‘The motor’s gone, better get the oars out, Hen. Can’t help much, I’m afraid.’ ” Orwell pointed to his chest. Dakin maneuvered the boat to a rocky island called Eilean Mòr, the last bit of land before the open ocean. Tossed by waves, the boat capsized. Orwell rescued Ricky from under it. Everything but a fishing rod and a couple of blankets was swept away.

The island was occupied by nesting puffins. Orwell got a fire started after his cigarette lighter dried out. A few hours later, they got the attention of a passing lobster boat by waving a piece of clothing from the end of the rod. The fisherman offered to take them to Barnhill, but Orwell said all they needed was to get to shore, even though he was the only one who still had shoes. A half century later, his niece and nephew were still stupefied (and angry) at having to walk back barefoot.

Many versions of this calamity have the boat capsizing at the edge of the whirlpool. “Their motor-boat was drawn into one of the smaller whirlpools and overturned. Fortunately, with Mr Blair’s help, they all reached a small islet,” read the account in the Glasgow Herald 11 days later. However, anyone who’s seen the whirlpool at Corryvreckan knows that if that had happened, Nineteen Eighty-Four would have ended in 1947.

If you write in a diary almost every day, and are famous enough that all your house guests are asked to record their memories, the world is going to learn a lot about you. That is certainly true of Orwell’s years on Jura. The writer’s diaries provide a record of his daily life in odd and exquisite detail. The entries invariably begin with an observation about the weather and end with the number of eggs collected that day, and the total since the flock was acquired. The day after the Corryvreckan mishap it was “5 eggs (291).”

Orwell was frugal with coal, kerosene, and gasoline—all subject to rationing. He kept an account of how much of each fuel the household was using, the rate of loss or leakage, and whether the supply would last until the next delivery. He also noted when to change the battery for the radio, which, aside from the mail, was his only connection to the wider world.

He did a lot of tinkering and building, often without the necessary skill and materials. “Put up sectional henhouse,” he wrote on April 13, 1947. “Wretched workmanship, & will need a lot of strengthening & weighting down to make it stay in place.” Two weeks later, while his son was recuperating from the measles, Orwell noted: “R. better. Tried to make jigsaw puzzle for him, but can only cut pieces with straight edges as my only coping-saw blade is broken.” When he lost his tobacco pouch, he made a new one out of a rabbit skin, lined with an inner tube.

He was an unsentimental naturalist. Rabbits were a scourge of the garden. One spring day while digging his recently plowed potato patch, Orwell uncovered “a nest of 3 young rabbits—about 10 days’ old, I should say. One appeared to be dead already, the other two I killed.” Occasionally, he showed flashes of cruelty. On a picnic to a nearby island, he and his companions encountered an adder, Scotland’s only venomous snake. Bill Dunn, the farmer who married Avril, recalled that Orwell held its head down with his foot and “deliberately took out his penknife and opened it and slit the snake from top to bottom. He degutted it, filleted it.” Orwell always disliked snakes, but I can’t help wondering what part of Nineteen Eighty-Four he was working on that week.

He could also behave in a way that doesn’t comport with his reputation as the tribune of the working man. In 1946, a few months after Orwell arrived in Jura and assembled his household, David Holbrook, the lover of nanny Susan Watson, came for a visit. A graduate of Cambridge and a tank commander during the war, he was also a member of the Communist Party, which made Orwell immediately suspicious. During Holbrook’s stay, Robin Fletcher visited Barnhill to discuss hunting. With him were several “beaters”—hired men who flush game. Orwell’s nanny and her boyfriend were given strict instructions to make themselves scarce.

“The laird was going to be entertained in the sitting room, which was not very often used, and they were going to have tea there, and we were not to appear,” Holbrook recalled in a 1984 interview. “Susan and I had tea in the kitchen with the beaters, and Orwell and his sister had tea in the sitting room with the laird, which we thought was very comic.”

Orwell doesn’t mention this, or other domestic dramas, in his diary. Neither does he talk about the progress of his novel (although he does occasionally in letters). We don’t know how he divided his time between writing and planting peas, poisoning rats, cutting peat, hauling lobster pots, fixing his motorcycle, and playing with his son. Visitors remember hearing him type in a room over the kitchen many mornings, appear for lunch, and then sometimes return upstairs to type some more.

He finished the first draft of Nineteen Eighty-Four in early November 1947, typing in bed because of illness. From that Christmas until midsummer of the following year, he was in a hospital outside Glasgow, being treated for tuberculosis. He undertook a second draft of the novel there.

Orwell returned to Jura on July 29, 1948, his health somewhat restored, and finished his rewrite in November. He was unable to find a typist willing to come to Barnhill, so he retyped the manuscript himself, again mostly from bed. He wrote a letter to a friend on November 15 saying that he was so weak that he couldn’t pull up a weed.

His final Jura entries are short. They describe no activity. On November 24, he wrote: “Cold during the night. Today fine & sunny, but cold. Wind in East. Wallflowers keep trying to flower.” Four days later: “Beautiful, windless day, sea like glass. A faint mist. Mainland invisible.” Their message might as well have been, “I am still alive.”

Orwell left Jura for the last time just after New Year’s Day 1949. He went to a sanatorium in Gloucestershire, England. In September, he was transferred to University College Hospital, London. He died there on January 21, 1950, after bleeding from one of his TB-damaged lungs.

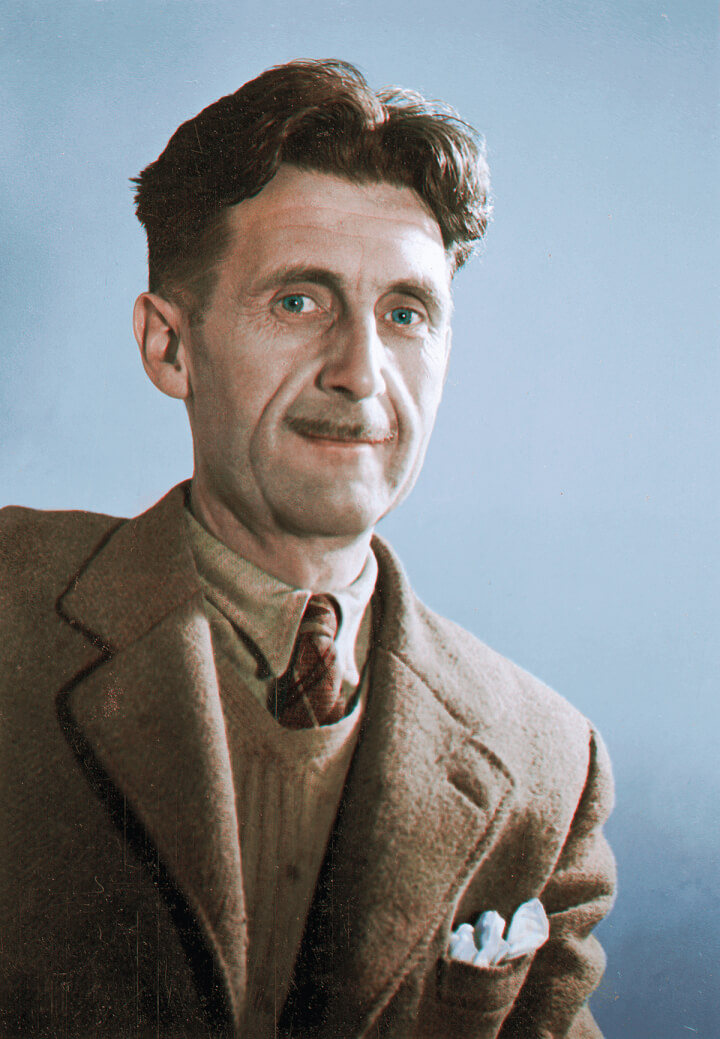

George Orwell, c. 1940. Curiously, despite his work as a broadcaster

for the BBC, no recordings of the writer’s voice are known to exist. (Wikimedia Commons)

So, is there anything about Orwell’s time on Jura that informs the book he wrote there? Or is the mystery of Nineteen Eighty-Four that it bears so little relationship to its creator’s life?

The answer to both questions is yes.

Although the novel begins on April 4, 1984, in the dystopian empire of Oceania, its inspiration was England, circa 1946. The food is bad, and there isn’t enough of it. (Meat was rationed in England until July 1954.) Whatever your vehicle, you’re constantly worried about running out of gas. Your house is cold, the plumbing leaks, and privacy is hard to find.

Winston Smith, whose evolution into an enemy of the Party is the novel’s narrative backbone, has more than a little of Orwell in him. Both have an aversion to sulfurous odors (cabbage, feces). Winston’s first transgressive act—starting a diary—is something Orwell had been doing for years. As Winston stares at his book’s blank pages, it’s hard not to hear the author talking to himself:

For weeks past he had been making ready for this moment, and it had never crossed his mind that anything would be needed except courage. The actual writing would be easy. All he had to do was to transfer to paper the interminable restless monologue that had been running inside his head, literally for years.

There are other grains of autobiography. When Winston goes to help unclog the sink of the woman in the neighboring flat, he hopes he doesn’t have to bend down, “which was always liable to start him coughing.” This was a problem Orwell had when gardening. Winston ruminates early in the novel that “in moments of crisis one is never fighting against an external enemy, but always against one’s own body.” Orwell must have felt the same when he twice left Jura to seek treatment for his failing lungs.

The inadequacy of Barnhill’s paraffin, or kerosene, lamps whispers in the description of how “the feeble light of the paraffin lamp” didn’t permit Winston to see that the prostitute he hired was a toothless woman in her 50s. Even in the famous scene in which Winston is shown the torture device made for him—a facemask attached to a cage of hungry rats—we find a precursor on Jura. In the diary entry for June 12, 1947, Orwell noted: “Five rats (2 young ones, 2 enormous) caught in the byre during about the last fortnight … I hear that recently two children at Ardlussa were bitten by rats (in the face, as usual.)”

But that’s about it. Nineteen Eighty-Four is an extreme product of the imagination. It didn’t just render life under totalitarianism, it imagined the R&D that would go into the totalitarianism of the future, much of which has proved true. That included the purging of the historical record, state control of procreation, government surveillance of public spaces by camera, and the invention of electronic screens that both project images and record activity that occurs in their presence.

One of Orwell’s insights was that there’s no best place in which to imagine such a world, so you might as well do it where you want. But if he thought Jura would be a quiet place without distraction, he was wrong. There were endless chores, things to fix, plans to bring to sometimes literal fruition, and a child to educate and entertain. Also, endless guests. When he returned to the island in July 1948 after seven harrowing months in the hospital, Orwell soon had so many summer visitors that he erected a tent in the yard to accommodate them.

His willingness to persevere on Jura in spite of ill health was almost universally criticized by his friends, who lamented his presence on the island. However, Paul Potts, an eccentric poet who met Orwell during the war, idolized him, and visited him on Jura, made an observation that gets closer to the truth: “Ever since I had known him he’d been given up as hopeless. During that time he’d lived a fuller life than a whole company of A.1 recruits.”

Jura was a strange choice, but almost certainly not one he made for show.

When I think of Orwell and Jura, what comes to mind is not the Corryvreckan calamity, or him tapping away in his upstairs aerie, or the image of a pulmonary cripple cutting 150 blocks of peat (which he did one June day in 1947). Rather, it’s an event on his next-to-last day on the island, sometime in the first week of January 1949.

Orwell had been confined to bed for a month. (“Have not been well enough to enter up diary,” he wrote after a 12-day gap in the record.) He was once again leaving to be treated for tuberculosis. The plan was to go to Ardlussa, spend the night with a villager, and travel south to the ferry terminal the next day.

His sister Avril and Bill Dunn, her soon-to-be husband, drove Orwell and Ricky in Dunn’s ancient Austin. On the way, it slid off the road into a ditch, becoming hopelessly stuck. (I have a friend who twice went into a ditch on Jura, requiring extraction by tractor each time.) Avril and Bill walked four miles back to Barnhill to get the “lorry”—a kind of pickup Orwell owned—while Orwell and Ricky stayed in the car.

“We just sat there together, talking,” a grown Ricky remembered years later. “It was raining. It was cold, and I do remember my father giving me boiled sweets. He was a very sick man, but he was quite cheerful with me, trying to pretend that nothing was wrong. It was getting dark by the time Avril and Bill got back with the lorry.”

Richard Blair was about to be orphaned a second time. This was one of his last memories of his father.

The lorry couldn’t pull the car out of the ditch. But as it happened, the accident was at one of the few places where a vehicle could detour onto the heath for a few yards. Orwell and his son were rescued and delivered to Ardlussa. From there, Orwell moved onward to Cranham Sanatorium.

Judy and I passed that spot in the road as we walked back from Barnhill on our endless June afternoon. I have no idea where it was exactly. At this point, probably nobody does. But it’s there someplace, a symbol of love and optimism, which are just two of the things defeated by the end of Nineteen Eighty-Four.