With the alders going brown, and the cottonwoods and birches turning yellow, it’s impossible not to obsess about the dying spruce trees. A nonnative species of aphid has killed—or nearly killed—trees all over town and across the bay.

The spruce aphid is originally from Europe, but has been in the Pacific Northwest for about a century. Warmer winters have given the insect a chance to multiply, even in the cold months. Aphids can give birth to live young. I watched this with a hand lens once when I was in college. Females can reproduce without males around, creating exact genetic multiples of themselves over and over and over again. It is eerie.

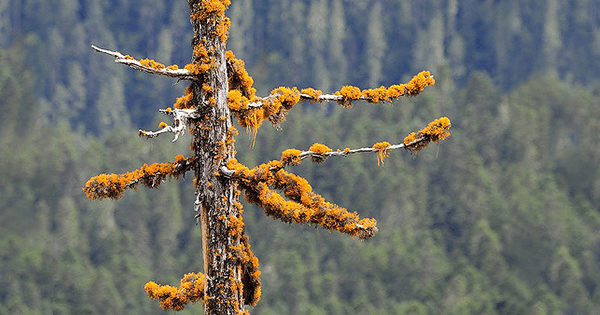

We have only one spruce on our quarter-acre property in town. It stands just outside our kitchen window and towers over the house. Except for the tips of the branches, the entire tree has turned brown, and it rises out of a circle of its own dropped needles.

The impact of this aphid epidemic, of course, isn’t about individual trees. It’s about the transformation of entire spruce forests. And nearly all of the trees below 350 feet in elevation have been affected. Experts advise property owners to leave the trees standing. The trees are likely still alive, they say—at least for now.

Less than 20 years ago, an explosion of spruce bark beetles ravaged local forests. As with the aphids, mild winters encouraged the beetles. At the peak of the outbreak in the 1990s, the insects were killing 30 million trees a year. In the end, the beetles leveled forests in an area the size of Connecticut. People living on tree-cloaked properties suddenly found themselves in meadows of stumps, feeling naked, or grateful for their new views, or both. The acres of dead trees invited wildfires, which further altered the landscape. Those beetles are still on people’s minds here. And even if the aphids don’t kill the spruce, they might make the trees more susceptible to future beetle attacks.

At this northern latitude, we have only four main types of tree: spruce, alder, cottonwood, and birch. Each one is critical not only to the ecosystem, but also to the psyche. Alders are the weed trees, but provide welcome green and privacy each spring. And they make the best marshmallow-roasting sticks. Cottonwoods often grow in glorious stands in the middle of spruce forests, and in the fall, they glow gold amid a sea of green-black. Birch forests are wondrous in every season: their pale, papery bark seems to hold every color. It’s possible to deeply love a particular birch, and there are special ones around town that invite wedding ceremonies and buoy swings.

The spruce has always been the workaday tree of this landscape—providing fuel for fires and raw material for kayak frames and cabins. The presence and absence of these trees mark the most striking transitions between habitats: from temperate rainforest to alpine tundra, from meadow to woods, from intertidal zone to forest.

Although I’ve never felt a particular fondness for the nearly dead spruce on our property, a hawk owl perched in it years ago, and the tree has provided a swath of blue-green that I have loved. No longer. It’s painful to lose a tree that is part of your daily life.

I know that the aphid outbreak is just one of the many changes we will see in the years to come. But it is hard to think about the coming decades, easier to consider the next few months. What we need is a cold winter, a real winter. It would clean the slate, reset our minds and our optimism about the future, and hopefully kill those damned bugs.