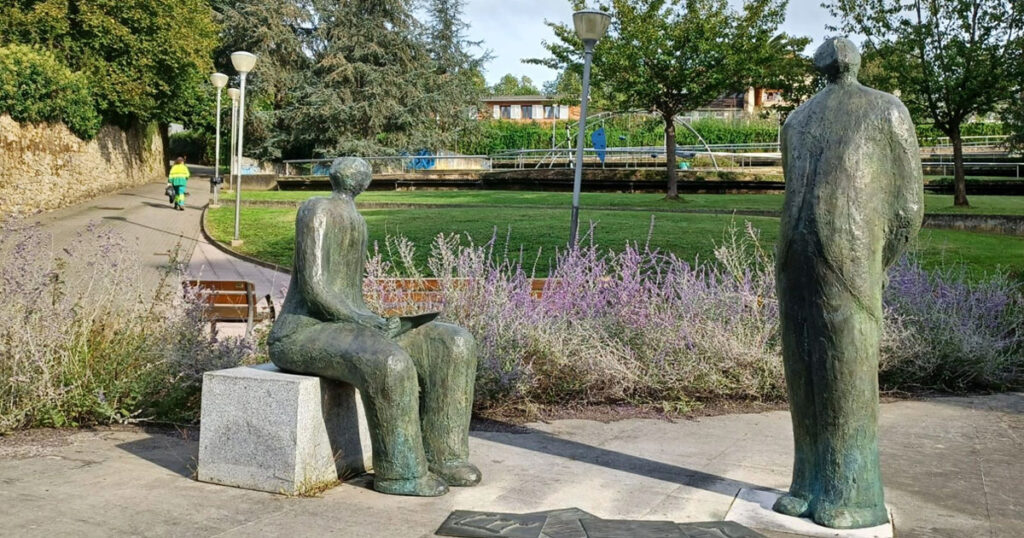

I discovered the Parque de la Música two years ago, in my first weeks in Pola de Siero, wandering with my dogs in the early morning through the new town. Nice tiered park, nice trees and bushes, nice bronze sculptures of two figures with a jumble of bronze sheets of music on the ground between them, a bronze plaque naming the two people to whom the park was dedicated. The names meant nothing to me, and I immediately forgot them. The park I’ve returned to a number of times in my walks with the dogs: a pretty, peaceful spot, always empty.

Fast forward two years. On the last Friday of May, a visiting childhood friend and I attended a concert in the Pola Teatro Auditorio, a massive building in a complex that includes a dance school and a cultural center with a library and an exposition hall. I had passed these buildings many times but had so far ventured into only one, the Casa de Cultura, which houses the library. I didn’t even know where the auditorium door was. My friend and I circled the building until we spotted what appeared to be a likely entrance. In we went.

The concert was a tribute to a musical celebrity of La Pola, Ángel Émbil, and consisted of performances by several choirs of the Siero Musical Society, starting with a trio of tots, who skipped and bounced to their places with their teacher, and ending with a choir with members between 18 and 65 years old, performing a quintet of pieces by Émbil. I was too far from the stage to see the singers’ faces, but even at a distance I could tell the singers’ ages from their gait. No confusing the loose, easy movements of the younger members with the stiff, uncertain motions of the older ones. Everything about the way the older singers mounted the low bleachers and turned to face the audience gave away their age. Perhaps someone could hear age in the mix of voices too. Not I, however. I could only say I liked their singing even better than the sweet clean voices of the children. My friend knows no more about music than I do, and her comment, like mine, was that she enjoyed the singing. Her son is an excellent violinist, and my brother plays a handful of instruments, but none of their know-how has rubbed off on us. Happily, expertise is not necessary to enjoy yourself at a concert on a Friday evening in late May, friend at your side. Neither was expertise required to savor a glass of wine at the bar where we stopped as we walked back to my house.

A few days later, the two of us, out early walking the dogs, wandered past the Parque de la Música. Reading the plaque, my friend noticed that one of the bronze figures depicted the same person honored in the concert. So it did. An Asturian from the age of 10, when, in 1907, he moved with his family from the Basque Country to Gijón, he later moved to La Pola, where most of his professional life was conducted. “Conducted,” I said. Would a good conductor know how to preside over his life? Maybe so: composing, teaching, and conducting until his death in 1980 made Émbil a beloved figure. I’m not saying you need to have a monument in your honor, but if you conduct yourself well, won’t there be a tribute in the hearts of friends and family?

We left the park. Only on the next visit, after my friend had left, did I notice that the park is shaped roughly like a theater, with the two statues posed on the low, stage end, the semicircular tiers expanding outward like the tiers in an amphitheater, the path along one side like an aisle. As on other occasions, I climbed the path, walked along those tiers to gaze down on the figures on the stage below. Not just a park but an amphitheater. Not just a musician but a maestro. Not just a friend but a super friend. To see it all clearly, you need only the right overlay. And time to line everything up, just so.