Physicist, Pacifist, Anti-Fascist

In dissent, Einstein affirmed humanity over nationalism

On the day I sat down to write this column, August 4, I realized that it was the 100th anniversary of Britain’s entry into the First World War, a momentous event precipitated by German’s invasion of Belgium, and decided to scrap a previous idea to devote this one to that prominent German pacifist Albert Einstein.

In October 1914, 93 German intellectuals, including Nobel prizewinners Max Planck and Wilhelm Roentgen, signed a Manifesto to the Civilized World in which they railed “against the lies and calumnies with which our enemies are endeavoring to stain the honor of Germany in her hard struggle for existence.” Nationalist chauvinism was sweeping Europe. “It is not true that Germany is guilty of having caused this war,” they insisted. “It is not true that we trespassed in neutral Belgium.”

Einstein refused to sign the document, writes Jamie Sayen in Einstein in America: The Scientist’s Conscience in the Age of Hitler and Hiroshima, and “in his first public political act,” became one of only four signatories of the Manifesto to the Europeans, which declared that it was the “duty of the educated and well-meaning Europeans to at least make the attempt to prevent Europe […] from suffering the same tragic fate as ancient Greece once did. Should Europe too gradually exhaust itself and thus perish from fratricidal war?”

What Sayen calls Einstein’s “instinctive pacifism” reflected his antipathy toward cruelty and hatred and his contempt for “the military mentality.” The 35-year-old theoretical physicist refused to aid in the German war effort and spent the first two years of the war working on and then publishing his general theory of relativity.

The war claimed the lives of 8.5 million soldiers on all sides, killed seven million civilians, wounded 20 million soldiers, and introduced chemical weapons, tanks, and aerial bombing.

On November 6, 1919—nearly a year following the signing of the armistice—British scientists announced that, after an expedition to the South Atlantic, they had verified one of the predictions of Einstein’s theory of relativity: that light passing near the sun would be deflected by the sun’s gravitational field. “In spite of the prevailing atmosphere of postwar hatred,” Sayen writes, “English scientists had just traveled several thousand miles to verify the theory of a German.”

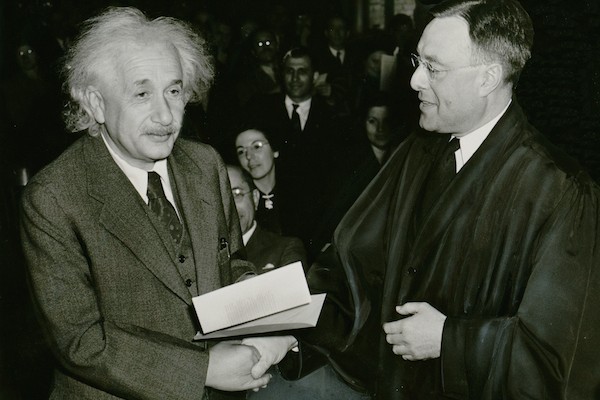

In October 1933, Einstein accepted a lifetime appointment at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, and later renounced his pacifism in the face of Nazi Germany’s war-mongering and persecution of Jews. In August 1939, he wrote a letter alerting President Roosevelt to the possibility that “a nuclear chain reaction” could lead to the construction of “extremely powerful bombs of a new type” and suggested that the president appoint a group of physicists to work on chain reactions in America. Einstein worked tirelessly to help Jewish refugees from Europe gain entry into the United States in the face of then-restrictive immigration laws.

“The Einstein Archives overflow with letters from refugees, and Einstein did everything in his power to help them,” Sayen writes. “He wrote affidavits for so many, despite his own limited resources, that by the late thirties his signature on an affidavit no longer carried much weight with the authorities. For others, he wrote letters to relatives, if they had any, or to wealthy nonrelatives who were willing to sponsor strangers.”

I have long admired Einstein’s decision to speak out against World War I (or, as the Germans called the first world war, Weltkrieg) when very few did, and when those who denounced the killing were scorned and ostracized. I also admire his decision to speak out against the use of nuclear weapons, “the most formidable and dangerous weapon of all times,” in a speech recorded in 1945:

We cannot desist from warning, and warning again, we cannot and should not slacken in our efforts to make the nations of the world, and especially their governments, aware of the unspeakable disaster they are certain to provoke unless they change their attitude toward each other and toward the task of shaping the future.