After two-and-a-half weeks with my folks in Durango, Colorado, this past August, being as useful to them as I knew how, I was home in Spain again. I looked around, lost. How to be useful to myself was the problem. I could not decide to tackle my own life, although, so shortly before, no problem had seemed too big, not even my father’s study. I’d looked with dismay on his thousands of books, hundreds with no proper shelf space, and yet had been able, forcefully, insistently, holding each volume before my dad for a yea to toss or a nay to keep, to help him cull 17 cardboard boxes-worth from his collection.

It seems to me he kept many more than he parted with, and that’s true. He owns thousands of volumes, and the job this summer was to get rid of just one section of shelving encroaching on the door, meaning either finding room for those books on other shelves or getting rid of them—of them and the many dozens that had piled up around his bed and chair and desk. But isn’t it true that he could have stood to part with almost any of his books? He could have said yes to the first 400 I asked about. Instead I had to practically wrest each book from him. Every negative I got peeved me a little. “Oh, Dad! You’re never going to read this again!” I said, to which he would answer, “I might.”

But now I miss my dad and his pushback against my push. “Gathering Evidence,” I had read from the spine. “Tennis and the Meaning of Life. Being and Nothingness. Ivanhoe.” For each I asked, “Save or toss?”

“Oh!” my father said in gentle thoughtful wonder about one book after another, as if he’d recently had on his mind that very volume. “Okay,” he’d say, slowly nodding.

“Okay toss?”

“No, no. Save.”

Finding 400 to give up took some days and some wheedling. But finally, we were almost done. I grinned at the book dealer, who was waiting patiently just inside the door of my father’s study for us to go through the last pile. He was getting a bargain—he’d have any of the selected books for his bookstore at the price he named, and would donate the rest to the library for their used-book sale. The boxes were already in his vehicle. I told him, “I need a better word than toss if I want my dad to give them up.”

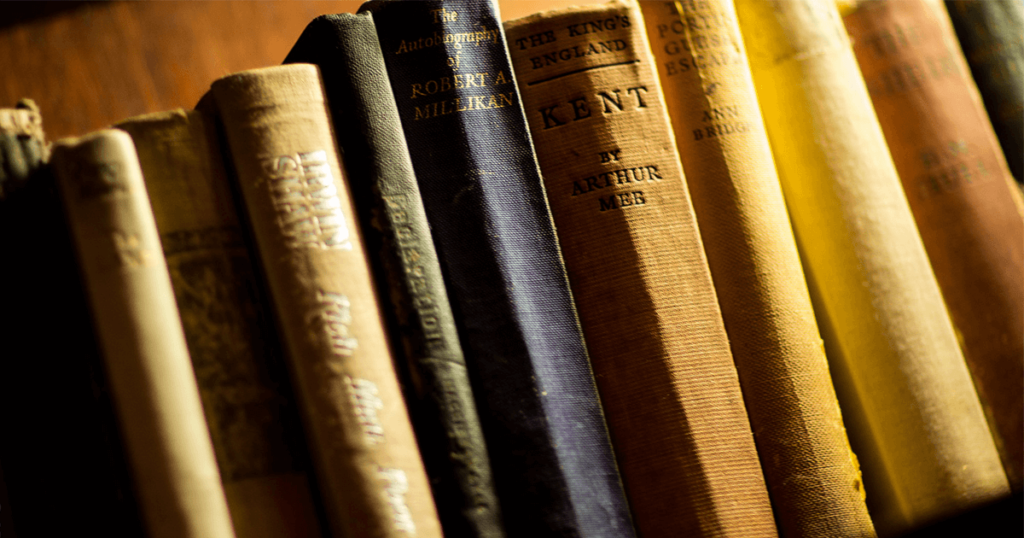

The book dealer had been eyeing my dad’s immense roll-top desk, covered with books and papers. I looked at it all again, too: the piled papers, the nameplate from my dad’s office door when he’d taught, the sole window letting in a hint of the slowly advancing day, the four lamps shedding warm pools of light on stacks of books and patches of floor, the armchair in the corner, the family portraits crowding the wall above the chair and the space over the door, and the four dark walls of books enclosing it all. History, philosophy, the Second World War, Paris, memoirs, books on photography, books by Georges Simenon, books about The New Yorker, all crowded into my dad’s study. Most of the fiction was shelved in the basement, more than he could ever read. They were all treasures. You don’t toss treasures. Some phrase like pass on, or make available to others would better suit the future envisioned for the books my dad was giving up.

The book dealer smiled, as if he’d read my thought and had that better word for what you do when you’ve had your fun and satisfied your hunger.

“Release,” he said, and I pictured a wriggling fish held firmly while a hook is freed from its mouth and before it is let go into the water, becoming just a flicker of light, then a shadow. Catch and release in English is pesca sin muerte in Spanish, fishing without death. My father was reaching for a book. I let him have it. He held it, longer than necessary. Perhaps tighter. Then, it was hoped, he’d loosen his hold and set the book free. Which is all very good for the book, but what about my dad?