Some professional activities are separate from everyday life; others, such as the culinary arts and architecture, intrude. Like a chef cooking for her family, an architect who is building a home, buying a home, or even furnishing a home, inevitably brings a professional bias to the task. So it was for me. During our time together, my wife, Shirley, and I shared six homes. I was not one of those architects who imposed their own ideas on others—not that that would have been possible with Shirley. Her strongly held views on domestic matters were often more practical, and more original, than mine. After years of looking at and visiting buildings with me, she had absorbed an architectural ethos, which she combined with her own innate taste. Of course, it was not all smooth sailing; sometimes I got my way, sometimes she hers.

A House in the Country, 1972–1974

Shirley with her grandfather, Oscar St.-Jean, on our wedding day

Who would have thought? Shirley and I would say to each other from time to time. One of those shorthand expressions of old married couples, it referred in our case to our long-standing union. Who would have thought? Certainly not I. She was a native Montrealer, half Anglo, half French Canadian; I was the son of expatriate Poles, born in Edinburgh and an immigrant to Canada. I was the product of a solid bourgeois background: my father was an engineer, my grandfather, whom I had never met, a banker. Shirley’s mother, Cécile, worked in a factory, and her grandfather, whom Shirley treasured, was, as I understood from her stories, a dedicated horseplayer. The only child of divorced parents, Shirley was raised by her mother in a large extended family, surrounded by her grandparents and numerous aunts. I grew up in a nuclear family, and my relatives were scattered—an uncle in England, another in France, aunts in Poland. I was a professor at McGill University, that is, an intellectual—most of what I knew about life came from books. Shirley had gone to work directly after high school, and her knowledge of life came from life. She had married young, and her daughter, severely disabled, had died as an infant; a divorce followed. More than pretty, Shirley was convivial and outspoken. I was shy, uneasy in crowds. Yet here I was with this remarkable woman—and she with me. Attraction of opposites? I suppose that cliché applies.

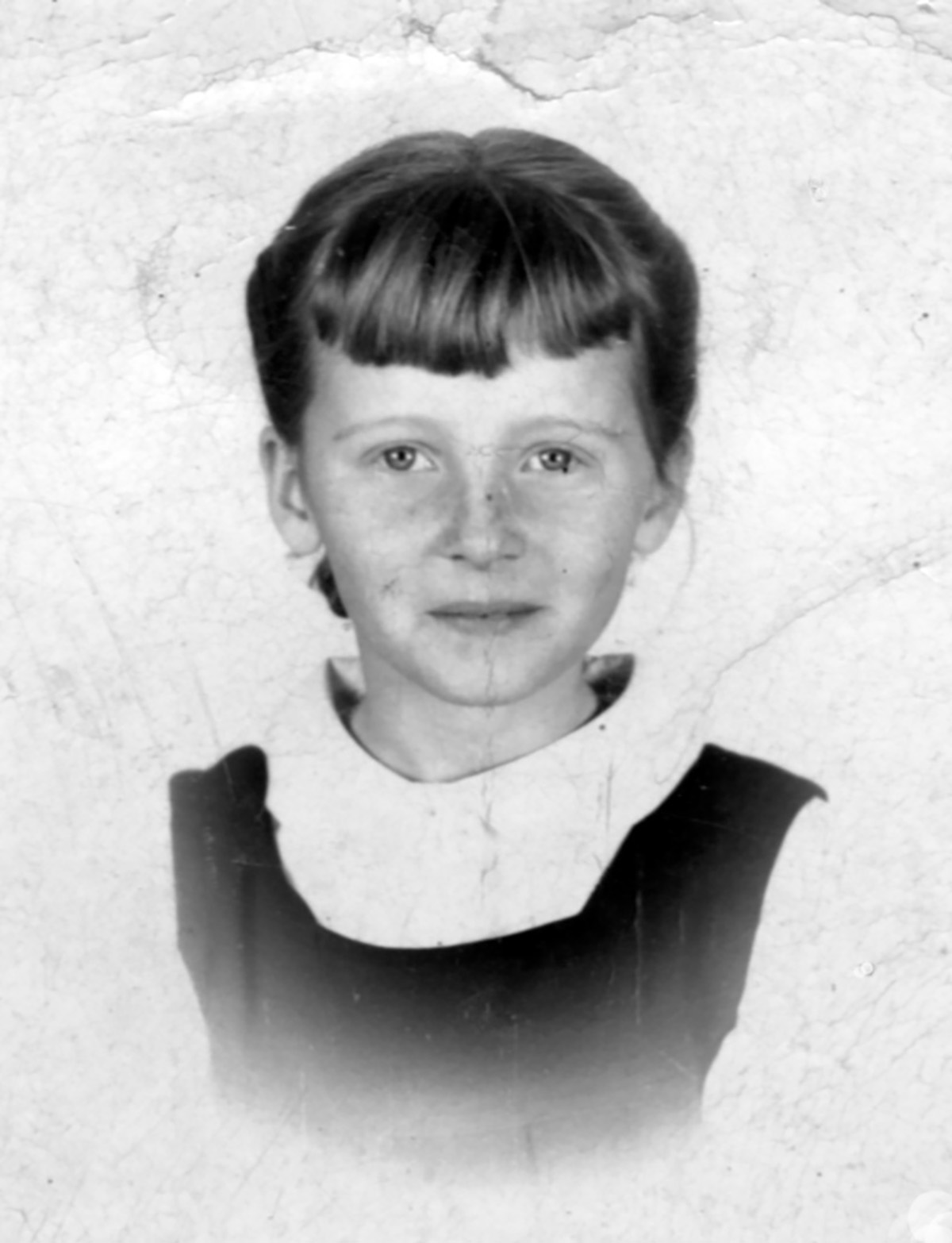

Yet attractions must share something. Shirley, a little redhead named Hallam, attended French convent schools in Montreal, where she was a bit of an outsider—as was I. We both looked back fondly on our schooling. Her teachers were sisters of the Congrégation de Notre-Dame; mine, in England and Canada, were Jesuits. My parents were wartime Polish exiles, and I was raised in England. Montreal is a cosmopolitan city, and Shirley had European connections; her ex-husband was from an Italian family, and when I met her she was living with a Hungarian photographer and working for another Hungarian émigré, a filmmaker.

Shirley and Attila, the photographer, shared a downtown Montreal flat with Jean-Louis, a French furniture designer. He and I worked in the same architectural office, and after we became friends, I saw the three of them frequently—I lived just up the street. Jean-Louis and Attila did not speak English well, so when Shirley wanted to see a new Hollywood film, we would go together—I was the one with a car, a Citroën deux chevaux. Being with Shirley was always fun; she was spirited, companionable, intelligent. There was nothing romantic about these outings; we just both liked movies.

Over the next couple of years, I moved on to other offices, other jobs. I still saw Jean-Louis—we worked together on an interior design commission—but he was now married and had moved out of the flat. I lost touch with Attila and Shirley. One day I ran into her on Sherbrooke Street. She told me that she and Attila had broken up several months before. She’d been in charge of production of short documentaries for Sesame Street, but the work had exhausted her, she said, and she had recently decided that she needed a break. That meant she had to move out of her current apartment, which was nearby, and find a cheaper place to live. Although generally circumspect, I am occasionally impetuous, and this was one of those times. Look, I said, I’m living in a big old house on Île Perrot. There’s way more room than I need. Why don’t you come. Try it. You can have your own bedroom, no strings attached. She said yes.

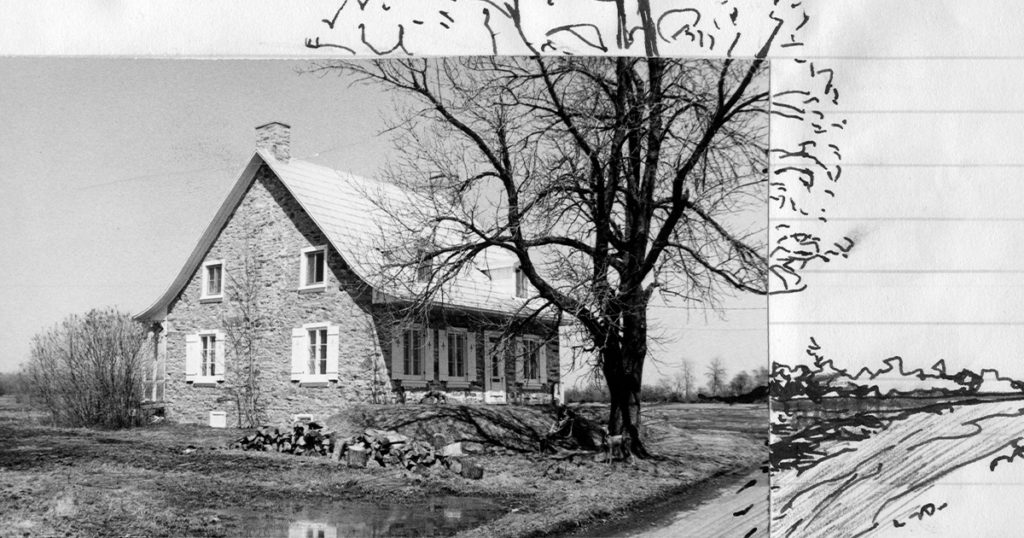

Île Perrot is one of several Saint Lawrence River islands that surround the large Island of Montreal. My house was on Pointe du Moulin, so named because an old windmill stood on a nearby windy point at the eastern end of the island. The circular stone tower was built in 1708, when the island was a seigneury—a feudal estate in the colony of New France. The house that I rented was old, too, a sturdy four-square structure with substantial stone walls and a very steep roof, architectural features derived from Normandy, where most of the early habitants originated. The pronounced bell-cast eaves, which are a distinguishing feature of traditional Québécois houses, were especially popular in the 19th century, which is probably when this house was built. It was too elaborate for a farmhouse, and there was no evidence of barns or outbuildings, so more likely it was a country retreat. The main floor was simply subdivided: a narrow stair hall in the center ; on one side, a living-dining room that stretched all the way to the back; and on the other, a front room that I used as a study and a kitchen. The attic floor under the roof contained three bedrooms. There were many windows and dormers, and the rooms were bright and sunny, especially in the winter when the ground was covered in snow. The house came furnished with rustic pieces to which I had added my Danish modern coffee table, a couple of director’s chairs, and a drafting table. Shirley’s furniture went into storage, except for a red Sacco beanbag chair.

The house was isolated, surrounded by open fields and shaded on the south side by a spreading oak. Immediately across the road flowed the broad Saint Lawrence. It was an idyllic setting. A house in the country was my dream; I’m not sure it was Shirley’s. As a youngster she had spent happy summers at her mother’s summer cottage on Lac Maskinongé, northeast of Montreal, but at heart she was a city girl. She had grown up speaking both French and English in Saint-Henri, a gritty downtown neighborhood at the foot of Atwater Avenue, not far from the storied Montreal Forum, where her mother sometimes worked as an usher. Saint-Henri was a working-class mixture of French Canadians, Irish, and Blacks, many of whom worked as railway redcaps—Windsor Station was nearby. Shirley played in the streets and alleys and sometimes snuck into Rockhead’s Paradise, a Black-owned nightclub that was a local fixture.

I had developed a taste for country living after spending three months on the Balearic island of Formentera, a Spanish whistle stop on the hippy Grand Tour: Haight-Ashbury, Marrakesh, Kathmandu. Of course, Île Perrot wasn’t Formentera, and Shirley, in her leather jacket, beret, and aviator glasses, wasn’t a hippy chick, but life in the old stone house suited us both. We bicycled in the summer and skied in the winter. We gardened. We got a dog, a Weimaraner named Duke. We were not recluses; the city was only a 40-minute drive away, so friends could easily visit. Most days I would go in to McGill, and Shirley would often accompany me, sometimes to work at the university, keeping the books for my research group, and sometimes to see friends. She kept her bedroom, but there were visits back and forth. There was no plan, it just happened. It was hardly puppy love: she was 28, I was 29. Who would have thought?

Balconville, 1974–1979

Following our second winter on Île Perrot, the owner of the house indicated that he did not wish to renew the lease. I’m not sure whether he wanted to sell the house or move in himself, but in any case, we had to find another home. It was agreed that we would move back to the city. By a happy coincidence, our friend Jean-Louis and his wife, Hildegard, had just bought a house and were vacating their rented flat. We knew it well—Jean-Louis had renovated it himself. The building belonged to a big development company that had acquired a dozen city blocks in the downtown neighborhood. The company had completed the first half of a large development that consisted of apartment buildings, offices, a hotel, and a shopping mall; the remaining several blocks it owned included Jean-Louis’s flat.

The developer, intent on preserving good community relations, was a congenial landlord, charging nominal rents and being quick to respond when repairs were needed. He had no objection to tenants making physical changes, since it was likely that at some future date the old buildings would be demolished. Jean-Louis had opened up some of the interior walls, removed the mantelpiece from the fireplace, exposing the brick, and replaced the counters and cabinets in the old kitchen. We happily took over the lease. The flat was on Jeanne Mance Street, where both of us—separately—had lived only a few years before. You could walk to the university, and it was close to Mount Royal, where we could run the dog. Saint Lawrence Boulevard, The Main, where Shirley shopped, was nearby: a Greek grocer, Waldman’s fish market, and a kosher chicken supplier—live poultry butchered and de-feathered while you waited. She always took Duke, who insisted on carrying a bag when they came home, but never on a leash; neither Duke nor Shirley believed in leashes.

The flat was part of a multiplex, a common Montreal housing type that consists of stacked flats, similar to a Boston three-decker or a Chicago three-flat, except that the Montreal plex is always a row house. A distinguishing feature is that each flat goes from front to rear, and each has its own front door to the street, the upstairs flats being entered off a second-story balcony reached by an open stair. The result is a streetscape of three- and four-story row houses behind a lacy screen of steel or wrought-iron balconies and staircases, some straight, some spiraling. This characteristic architecture is captured by the title of David Fennario’s 1979 play about a working-class Montreal neighborhood, Balconville.

Unlike triple-deckers and three-flats, Montreal plexes were not confined to blue-collar neighborhoods. Our 19th-century building, with its imposing limestone façade and large bay windows, was located close to Hôtel Dieu, the oldest hospital in the city, and it was originally intended for well-to-do doctors and senior hospital staff: spacious two-story flats, one on top of the other. To reach our front door, you climbed a tall outside stair. At the top were two doors: one to the lower flat, with main rooms on the second floor, and one to the upper—ours. The door opened onto a small landing at the foot of a tall stair. At the top of the stair was another landing where you left your winter boots and overshoes before entering a generous hall. The flat was large, almost as large as the Île Perrot house. The main floor, which had tall ceilings, was similarly subdivided: half was a front-to-back living room and dining room, separated by an arched opening that originally had pocket doors; the other half consisted of a front room that I used as a study, the stair hall, and a kitchen in the rear. A rather grand curving stair led upstairs, where there were three bedrooms and a small room that we used as a darkroom—we were both photographers. The bathroom had a huge old bathtub where even I, a six-footer, could luxuriate. The toilet was in a separate room—European fashion—lit by a skylight that also illuminated the hallway and the stair.

The kitchen opened onto a narrow-roofed balcony—called a gallery in Montreal—that gave access to an enclosed back stair and included a small plywood table where we spent many warm summer evenings eating and drinking. The gallery overlooked a treed back alley, a common feature in downtown Montreal, originally used for delivering coal and removing trash. Over time, people added garages, and if we looked down, we could see the metal roof of ours, which had been painted by Daniel, an artist friend of Jean-Louis, with a big red and green apple.

It was early summer when we moved in, and by the fall, once we were settled, we thought it would be nice to have a party in our spacious new home. Shirley said that if we were going to throw a big party—we had never done that before—we needed a reason. What exactly were we celebrating? A housewarming? Returning to the city? I’m not sure who suggested a wedding. I don’t remember a formal proposal or even much discussion. Once said out loud, even casually, there was no going back—neither of us could think of a good reason why not.

We got married on a cold Friday in mid-November before a judge in the Palais de Justice. Shirley’s best man was her friend Dominique; mine was Wajid, a friend from work. Shirley may have been casual about getting married, but that didn’t mean she shouldn’t have a wedding dress. She bought her clothes from a little shop on The Main run by an outré designer who made her a floor-length dress with a high neck and long sleeves, almost a nun’s shift, if nuns wore white cotton jacquard with a tutti-frutti pattern. The party was in the late afternoon. The invitation said no gifts please, just bring a cake and we will supply the champagne. I bought four jeroboams of Mumm. I also went to Dionne’s—Montreal’s Fauchon—for fresh strawberries, a winter treat in those days. It was a mixed group: our families, Shirley’s aunts and nieces as well as her grandfather, my brother and his wife, Montreal friends, Polish friends, university friends and colleagues, old students. All in all, a success.

Years later I came across a New Yorker cartoon of a wedding reception. The newly married couple is circulating, and the veiled bride, holding a bouquet, is cheerfully addressing a table of nonplussed guests. “Oh, we’re just here for the party,” the caption reads. That was us.

The Boathouse, 1979–1993

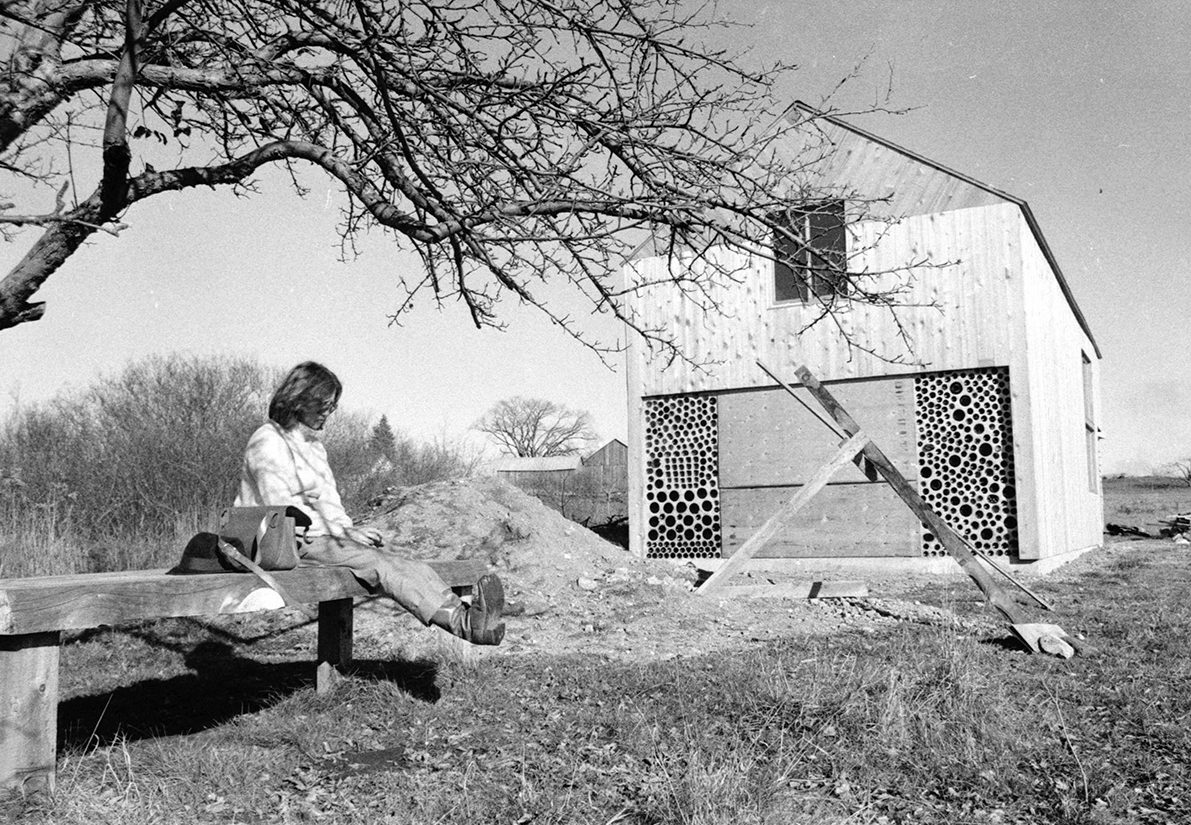

The Boathouse under construction. Building your own house brings feelings of fulfillment but also bouts of depression.

Our third home came about more or less by accident. I had become consumed by the idea of building a wooden sailing boat. My woodworking experience was limited—as a teenager I had built a leaky dinghy from plans in Popular Mechanics—and I knew that I would never master traditional boatbuilding with its steam-bent frames and lapstrake planking, but I came across a boatbuilder who had developed designs using plywood, which I thought I could handle. I sent away for plans. Now I needed a place to build.

That is how we became the owners of a small acreage outside Hemmingford, a village one hour’s drive from Montreal near the New York State border. My reasoning was that because it would take several years to complete my project, I would need a sheltered workspace. If we bought a piece of land outside the city, I could build a shed and, sometime in the distant future, we could add on to it and have a summer cottage. What did Shirley think of this? A summer cottage in the country is a Canadian institution, so she needed no convincing on that score, and she had her own childhood memories of Lac Maskinongé. Like me she was charmed by the location. Hemmingford was apple-growing country, and our land included a small orchard, as well as rolling fields and a stream deep enough to swim in. A lakeside site would have made more sense, but waterfront real estate was too expensive. As it was, we were stretched thin; the apple grower who sold us the 12-acre parcel agreed to payments spread over several years.

Shirley held her counsel regarding boatbuilding. The romance of yachting held no attraction for her, but she was prepared to humor me. Perhaps she expected that my enthusiasm would blow over. We set about building the workshop. We mixed concrete, sawed wood, and hammered nails. While our friend Vikram and I poured the concrete for the floor slab, Shirley troweled, and after we nailed up the sheets of wallboard, she plastered joints. It took a couple of years, and the result resembled a little barn covered in cedar siding. The barn was divided into a workshop with a loft for storing materials, and a small room at the other end where we could sleep over. I added a sauna, to revive the weary boatbuilder.

At some point the weary builder reached an unexpected but unavoidable realization: he was never going to build the boat. Building the workshop by hand (we initially had no electricity) had fulfilled whatever desire I had for woodwork, and it had also made me realize my limitations. I really didn’t have the temperament, the finickiness and necessary attention to detail, required to build a boat. Shirley and I had talked of eventually adding a house to the workshop, but I didn’t think that was going to happen either. Do-it-yourself building is a demanding process, full of disheartening mistakes and frustrating dead ends, of which we had had our share. Devoting yet more years to building an addition would put a needless strain on our marriage; we had stumbled into this project, but we had no reason to stumble further. There was a final consideration. The developer who owned our Jeanne Mance flat had run into trouble, and he had sold his unbuilt properties to a government-backed nonprofit that planned to renovate the old plexes and turn them into affordable housing and co-ops. It promised to be a long, drawn-out process with endless community meetings. That did not appeal to us. So we decided: we would convert the workshop, in which we had invested so much time, into a house and move to Hemmingford.

Our little barn was the built equivalent of a small cottage, although it would be necessary to subdivide the interior to accommodate a kitchen and bathroom. The room beside the workshop could serve as a small sitting room, enlarged by a built-in divan; with the addition of a closet, the space above would make a good bedroom. The workshop portion easily became a large farmhouse kitchen with plenty of space for a dining table. I inserted a tall, narrow window facing the long driveway, so that you could see visitors arriving. To accommodate the bathroom, I added a second floor over the kitchen, leaving a tall opening between the two levels; the loft did double duty as a study and guest room.

Shirley had been content to leave me on my own when I was building a workshop, but if this was to be our home, she had definite views on the subject. For example, she objected to my plans for the bathroom. Why couldn’t it be larger? she asked. I tried to explain that space was at a premium in our small house, but in the end, I had to admit that she was right—we spent a lot of time in the bathroom. It should be generous. We ended up with a room that was twice as large, and rather than a separate shower stall, all the surfaces were tiled and the whole floor sloped to a drain. Shirley also had thoughts about the kitchen. She had read a New York Times article about the kitchen in Frank Gehry’s house, which had an asphalt floor that could simply be hosed down. That appealed to her. Because ours was a small house, I wanted the same material throughout the first floor and I didn’t fancy asphalt in the sitting room, so we compromised on large terracotta tiles, attractive and easy to clean.

It wasn’t that Shirley was stubborn; she was simply more aware of the minutiae of domestic life and, unhampered by professional training, she was willing to question convention. For example, she didn’t like kitchen counters with deep base cabinets and difficult-to-reach wall cabinets. Couldn’t a kitchen be more like a workshop, she asked, with tools conveniently at hand? I designed a long counter that did not reach the floor, with shallow drawers for utensils and cutlery and deeper drawers for mixing bowls and appliances—no cupboards. Jean-Louis built it for us, and we used leftover floor tiles for the countertop. Instead of wall cabinets, I made a wooden wall rack for hanging pots and pans, knives and spatulas. On an outing to an Ontario flea market, we found an old wood-burning cookstove complete with a warming drawer and a copper water reservoir. The stove worked well once it got going, and the oven produced the best lasagna Shirley had ever made.

There were two subjects on which she was willing—with some reluctance—to compromise. They both involved features that grew out of my university research. One was the bottle wall. Recycling and reuse were two of my interests, and I wanted to incorporate a section of wall made from used bottles. In truth, my chief reason was aesthetic—the sun shining through the emerald and amber bottles had the beautiful effect of a stained-glass window. The bottles were set in concrete with their bottoms facing outward, which made a pleasing pattern on the exterior: wine bottles, Cinzano bottles, square gin bottles, large gallon jugs, the four jeroboams that I had saved from our wedding. The interior was a forest of protruding bottle necks, a dust catcher and impossible to clean, which did not thrill Shirley. The Swedish composting toilet was another of my research interests. The large plastic tank was located immediately below the bathroom, hidden behind a wooden screen. The tank was vented to the exterior and functioned well—it also composted food scraps from the kitchen. The lower end was fitted with an access hatch through which the composted material was annually removed. Shirley appreciated the environmental benefit of a waterless toilet, and the odorless compost resembled peat moss. It was bringing a wheelbarrow into the house that she never could quite come to terms with.

I had intended the workshop to look like a small barn to suit its rural surroundings: a boxy form with a largely windowless façade facing the long driveway. Shirley didn’t complain about this, but I could sense her dissatisfaction—the severe barn didn’t look very welcoming. I added a screened porch at the kitchen end. That helped. About a year after we moved in, I extended the other end. Living in the house, we realized that we needed the equivalent of a garage—a place to put a freezer, keep garden tools, and store firewood. I built an unheated storage room, separated from the house by a breezeway. Above the breezeway, I added a small study off the bedroom. Facing the driveway, I built a little entrance porch, just a roof supported on two columns. When we drove down the long driveway at night, the porch with its corrugated fiberglass roof glowed like a large lantern. Now the little barn looked more like a cheery home. We named it the Boathouse.

An Old Garden Suburb, 1993–1999

Thirteen years later, after I was offered a position by the University of Pennsylvania, Shirley and I moved to Philadelphia. We looked for a house in Chestnut Hill, an old garden suburb at the edge of the city. The picturesque gorge of nearby Wissahickon Creek had been a famous scenic landscape in the 19th century; Edgar Allan Poe had described it as “of so remarkable a loveliness that, were it flowing in England, it would be the theme of every bard.” Thanks to such encomiums, the surrounding area became a place where upper-middle-class Philadelphians built summer retreats and found relief from the sweltering heat. In the 1880s, a new railroad spur linked Chestnut Hill to downtown, and under the eye of George Woodward, an enlightened developer who was influenced by the British Garden City movement, a leafy suburban community took shape. Woodward, something of a philanthropist, built a variety of houses, from high-society mansions to compact row houses for young families.

With our discounted Canadian dollars, we had difficulty finding a house that we liked and could afford, and after a fruitless summer we were resigned to renting an apartment. At the last minute we came across a small house on Rex Avenue. The house dated from the 1890s and, like many of the older houses in Chestnut Hill, was built of locally quarried Wissahickon schist. The tall stone building with deep shuttered windows and a decorated gable was worlds apart from the Boathouse. The fall day we arrived was not auspicious. After the moving van was unloaded, we discovered that much of our furniture, including our bed, would not go up the narrow winding stair. We sat in the small living room, surrounded by stacks of cardboard moving boxes—all those books!—and, I’m ashamed to say, we broke down and cried. A new job in a new country, a new house in a new place—it was all too much.

The next morning things looked less grim. I moved the bed upstairs in pieces, and we found alternate places downstairs for the other furniture. There was much to do, and since I did not have to start teaching until the new year, we got down to it. A previous owner had removed the wall between the dining room and living room, presumably to “modernize” the house. Instead, it simply looked odd, a Victorian lady in shorts. I resolved to put the wall back and re-create a more traditional interior. The kitchen had been added to the house sometime in the 1960s, a bright, attractive room with a continuous band of windows on two sides, although very little storage space. I built open shelving as well as a floor-to-ceiling wooden rack for hanging pots and pans. We replaced the gas stove and treated ourselves to a Sub-Zero refrigerator.

The outdoors needed a lot of work. There was a nice brick terrace behind the kitchen, but the garden was a mess. The house was tucked into one corner of the small lot, and much of the leftover space was taken up by an asphalt driveway and a parking area. With the help of a landscape architect colleague at Penn who was also a neighbor, we replanned the garden, cut back the driveway, added a stone retaining wall, restored the lawn, built a front walk, and planted trees and shrubs. One feature of the garden in particular had attracted me to this property: a small garden house, an attractive old building from the previous century that had been recently renovated and would make a perfect writing studio. I moved in IKEA shelving as well as the long dining table that I had built when we lived on Île Perrot.

Putting our stamp on the house and garden during our first year in Philadelphia helped to ease the move from our handmade home in rural Hemmingford. Chestnut Hill was hardly the city, but shops and restaurants were nearby and there was the Wissahickon for longer walks. It’s true that our house was pretty small. I sketched possible additions, but none really worked. In any case, I liked the compact interior, which reminded me of the Boathouse. I was surprised to learn that Shirley did not share my enthusiasm. During a conversation it emerged that although she enjoyed our garden, she was not as delighted as I with the house. Despite the interior modifications, she disliked the small rooms and the steep stair. She reminded me of a large house that we had come across during our house hunting. I had made an offer but was unwilling to raise our bid sufficiently, and the house had sold to another buyer. Shirley was not recriminating, but I felt I owed her. I had not exactly dragged her to Philadelphia—we had both felt that it was time to leave Quebec with its separatist politics (see “Words Apart,” the Scholar, Summer 2009). But I had to admit that the purchase of the Rex Avenue house was precipitated by the pressure of moving and—if I was honest—by the attractive little writing studio. So I agreed that we should keep an eye out for a larger home. We both liked the neighborhood, so we would not look far afield. And this time we would not be rushed.

The Icehouse, 1999–2017

The secluded terrace of the Icehouse, with its massive retaining wall and rhododrendons, during a rare snowfall

One day the following year, Shirley excitedly showed me an ad in our neighborhood newspaper, a grainy black-and-white photograph of a house, or rather the entrance to a house, a hooded canopy with heavy beams supporting a slate roof, a double door with elaborate glazing, and small side windows. I think we should look at this house, she said. It’s a private sale, so we mustn’t delay. I wasn’t sure exactly what she saw in the ad, but I thought, Why not? I had to be in Washington for a lecture that Thursday night, but I got back on Friday and we drove over. The address was near the edge of Chestnut Hill. The old stone house sat high above the street; we must have passed by it scores of times without noticing. The front door with the hooded canopy was at the top of a long flight of stone steps. We knocked and were let in. People sometimes talk about “curb appeal” in a derogatory way, as if it were something superficial and fundamentally deceitful. But first impressions are important, and our first impression of the interior was of space: a generous stair hall that extended into a living room on one side and a dining room on the other. The openings were framed in rough timbers rather than moldings, and rugged wooden beams supported the ceiling. The wood was stained dark brown and contrasted with the sand-faced plastered walls. Older houses in Chestnut Hill tended to be staid American Colonials; this was a cross between a rustic Japanese teahouse and a Bavarian hunting lodge. Shirley and I grinned at each other. It was what the French call a coup de foudre—that is, love at first sight.

We were given a tour of the house. A smallish kitchen, a breakfast room, a glazed sun porch. Fireplaces in both the dining and living rooms, the latter huge and built of fieldstone. Bedrooms and bathrooms upstairs, and more bedrooms on the spacious attic floor. The owners explained that they had been in the house only a year, but an unexpected job offer in San Francisco necessitated the sale. Their asking price was a lot more than our Rex Avenue house, but a lot less than such a large house would normally cost, probably because it faced a busy street and had no garage or even a driveway, only on-street parking. The sellers were obviously pressed to move, and two days later we made an offer—no home inspection, no contingencies, as is. Five days later, we signed an agreement, and two weeks after that, with our respective lawyers, we met with a notary to finalize the sale. It was all very impetuous, a headstrong romance. There was a nervous period when we found ourselves the owners of two houses, but in due course we had a buyer for the Rex Avenue house and had secured a mortgage from the bank. Six weeks after that first visit, we moved in.

Our new home had an interesting history. It started life in the early 18th century as a barn built into the side of a hill, part of a large estate. At some later date, after the estate was subdivided, the barn was turned into a community icehouse. In 1907, after a new larger icehouse was constructed nearby, the old icehouse was converted into a residence. The work was done by H. Louis Duhring, a young local architect who would go on to design many houses in Chestnut Hill (by curious coincidence, his own home was next door to our Rex Avenue house). Duhring demolished the upper part of the old structure, keeping only the basement and the wooden floor above; its structure was unusually massive to support the weight of ice blocks. On top of the old walls he built a brand new house. Duhring was interested in old European styles—the décor of his own house was Spanish—which may explain the gemütlich interior. On the exterior he incorporated features of a Norman farmhouse: rusticated stonework, a steep slate roof without eaves, and stepped gables at each end. To one of the gable walls he affixed a wrought-iron monogram: I C E. The Icehouse.

One of the most attractive features of the house hadn’t made a big impression during our first lightning visit. In the rear, Duhring had cut into the slope to create a shaded slate terrace the length of the house. Over the years rhododendrons had established themselves in the massive fieldstone retaining wall, turning it into a vertical garden. This unexpectedly romantic and secluded terrace contrasted with the otherwise rather severe exterior.

Eventually we had the outside of the house repainted: dark brown for the woodwork, green for the underside of the canopy, brick red for the front doors. There was little to do on the interior; the living and dining rooms were largely unaltered from 1907. The second floor had been partially renovated sometime in the 1950s, judging from the pastel-colored tiles and retro fixtures in the bathrooms, which appealed to Shirley. I connected two of the smaller bedrooms to make a writing studio. The only room that we were unhappy with was the kitchen. The small room had been renovated a decade earlier by someone who was more interested in decoration than cooking. There was a wall oven and a Jenn-Air range, but little counter space. The ugly floor was multicolored ceramic tiles masquerading as slate. It didn’t help that the previous owners’ favorite color was baby blue. I painted over the offensive color and removed the wall cabinet doors, but having just blown our budget on the house, we agreed that we would have to live with the less-than-ideal arrangement.

Twelve years later our old Sub-Zero started to malfunction, and in the process of replacing the refrigerator we decided to make some adjustments in the kitchen: fix the cracked plaster, improve the lighting, maybe change the flower-patterned backsplash tiles that had always been an irritation. One thing led to another, and what began as a piecemeal improvement project ended with a completely gutted room. We started over from scratch. The work was a three-way collaboration between Jay, our contractor, Shirley, and myself. The result combined Jay’s craftsmanship, my architect’s eye, and Shirley’s desire that the kitchen should be a workplace rather than a showpiece. She was an accomplished cook—during our time in the Boathouse she had cooked her way through two of Marcella Hazan’s cookbooks. By relocating the main fixtures in what had been a dysfunctional arrangement, I was able to create a practicable work triangle of sink-refrigerator-stove—a kitchen requirement that had stuck with me from my schooldays. The ersatz floor tiles were replaced by oak, the granite counters were recycled from the old kitchen, as were the base cabinets, one of which Jay converted into deep drawers at Shirley’s request. He also found nice-looking adjustable track shelving to replace the upper cabinets. To expand the counter space, we added a cantilevered butcher-block slab that doubled as a bar counter.

A 1910 article in House Beautiful magazine described the Icehouse as “a thoroughly livable home,” and so it was. We used different parts of the house at different times of the year—lunches in the sunroom in the spring and on the shaded terrace in the summer, winter dinners in the dining room, or sometimes in front of the big fireplace in the living room. We occasionally used the breakfast room, but mainly it was a place for playing Scrabble. The house shone when it was full of people, and we held a big party for friends every New Year’s Day. We celebrated our 60th birthdays, then our 70th. Shirley had long since ceased being a redhead; her hair had turned pale blond, although she still had her mischievous smile and ready laugh.

We had been living in the Icehouse for 17 years—longer than in any of our previous homes—when Shirley tentatively suggested that maybe it was time to start thinking about moving to an apartment in the city: somewhere smaller, easier to keep up, where we wouldn’t have to drive everywhere, shovel snow, and take care of the many chores that the large old house demanded. She didn’t make a big thing out of it—I should just think about it, she said. Her suggestion caught me by surprise. I had retired from active teaching some four years earlier, and in a vague way I thought we would live here forever. But I had to admit that her judgment was more realistic. I started by clearing out the basement. In February, I made an appointment with a downtown real estate agent.

A Loft by the Schuylkill, 2017–2021

Our loft on the 11th floor looked out over the Philadelphia skyline. The varied furniture was like a tableau of our life together.

We spent a month and a half looking for an apartment. It was harder to find something than I thought it would be. We didn’t like new apartment buildings—too much glass and the rooms tended to be small. Older apartments had larger rooms, but they still felt cramped compared with the Icehouse. We wanted to downsize in terms of space, not quality. I liked one apartment building that was a bit pricey because it faced Rittenhouse Square, but when we came back for a second visit, the apartment had already sold; I think Shirley breathed a sigh of relief—she said that the labyrinthine layout didn’t appeal to her. One day, scrolling through a real estate website, I came across photographs of an apartment in an old industrial building that had been converted to residential use. What caught my eye was a trivial detail: dark blue tile in what looked like a largish kitchen. We had not looked at any loft apartments, although they were common in Philadelphia, which had once been an industrial powerhouse, its downtown dotted with factories, assembly plants, and warehouses. I thought it might be interesting to see the loft with the blue tiles, and I asked Jeff, our agent, to arrange a visit.

The building, a 12-story industrial block, was in the Logan Square neighborhood, a stone’s throw from the Schuylkill River. In most of the apartment buildings that we had visited, the corridors were narrow passages; here they were eight feet wide with tall ceilings. That was promising. Jeff unlocked the door to the apartment and motioned us in. The unit was basically one large space. The open kitchen was roomy and included a wide quartz countertop that did double duty as a bar. And the dark blue tiles were attractive. We took all that in later, because our attention was drawn first to the ceiling height—12 feet—which created an airy feeling, almost like being outside, and second to the dramatic 11th-story view offered by the factory sash windows: a downtown skyline of tall apartments and office buildings dominated by Norman Foster’s new 60-story Comcast tower.

In some ways, the openness of the loft reminded me of the Boathouse, which had only two enclosed rooms—the bathroom and the sauna—and two-story openings that gave the impression of one continuous space. The main living area of the loft was overlooked by a raised platform-like bedroom that was up a half flight of steps. The only doors belonged to the two bathrooms, one off the bedroom and one downstairs, and a small utility room. The open space near the front door, which the real estate fact sheet insisted on calling a second bedroom, would make a nice study and TV room. I could imagine living here, I said to Shirley, as we walked around. So could I, she said.

Neither of us had previously considered a loft, but in hindsight it was the perfect solution after the beautiful Icehouse—something completely different. The loft was about a third the size of the house, but because of the tall ceiling and because it wasn’t cut up into rooms, it didn’t feel small. Nor did it feel particularly domestic, with sprinkler pipes, air ducts, and track lighting suspended from the ceiling. There were traces of the original industrial building, not only the large, gridded windows but also the sculptural shapes of the reinforced concrete columns that engineers call mushroom columns. The building had been constructed in 1913 by the Larkin Company, a soap manufacturer and national mail-order company that a decade earlier had hired Frank Lloyd Wright to design its headquarters building in Buffalo. The Philadelphia branch was designed by a lesser light, C. J. Heckman, a Buffalo-based architect about whom the Internet provides no information at all. His design, while modest in keeping with the function, was well thought out, a very early example of reinforced concrete construction. A curious detail: the builders used corrugated metal sheets for the formwork of the concrete floors, which produced an unusual but not unattractive rippled effect on the ceiling.

We were fortunate that the loft was spacious because we spent a lot of time at home during the Covid pandemic; I wrote, she read, we listened to music and played Scrabble. Shirley developed an addiction to afternoon reality court shows, Judge Mathis and Hot Bench her favorites. We had downsized considerably before moving, keeping only our most valued possessions: my old rosewood coffee table, a leather settee that dated from our time on Jeanne Mance, an antique Québécois chest, a scarred 1950s Florence Knoll credenza from the Icehouse. Across the room, next to the bookshelves, was the long cherrywood dining table that we had bought after moving to Rex Avenue and Czech bentwood chairs that dated from the Boathouse. When Shirley got up in the morning, she could look down from the raised bedroom on this tableau of our life together. What a beautiful place we live in, she used to say. She loved the view out our windows—the roofs of the surrounding neighborhood, the children running around the rooftop playground of the nearby Montessori school, the distant dome of the Roman Catholic cathedral, and at night the illuminated steeples of the Mormon temple. After almost four decades, the city girl was back in the city.

It was during our fourth spring that this urban idyll was abruptly and unexpectedly cut short. A visitor to the loft in May would have encountered an incongruous sight: the dining table and bentwood chairs were moved against the wall and in their place stood … a stark metal hospital bed. One night Shirley had awoken with difficulty breathing. At first the doctors thought it was pneumonia, but it turned out to be much more serious, an acute failure of a heart valve. She was 77, and for various medical reasons we decided against open-heart surgery. While Shirley was in the hospital, she kept asking when are we going home? Soon, I said, and a week later we were back in the loft. Bedridden, she could watch me working in the kitchen; I could look down on her from the bedroom when I got up in the morning and last thing at night. She preferred to be alone, and there were no visitors, other than a regular succession of home-care workers and hospice nurses. Shirley put up with the indignities of bed care without complaint. She ate a little and accepted an occasional sip of wine. She didn’t want music or entertainment, no forced good humor or false sentimentality. Whenever I strayed too far into the latter domain, she would look at me sternly and say, “That’s enough.” Willful as always, in one of her last acts, she turned down a medication I offered her; she must have known she no longer needed it. That was in July. And so the story that began in an old stone house facing the broad Saint Lawrence ended here, in an airy loft beside the Schuylkill, an urban river that Shirley called our Seine.

Shirley, 1954. She is 10, and all her best qualities are already in evidence in her forthright gaze: good humor, intelligence, and moxie—she is fearless.