Present-Day Thoughts on the Quality of Life (1969)

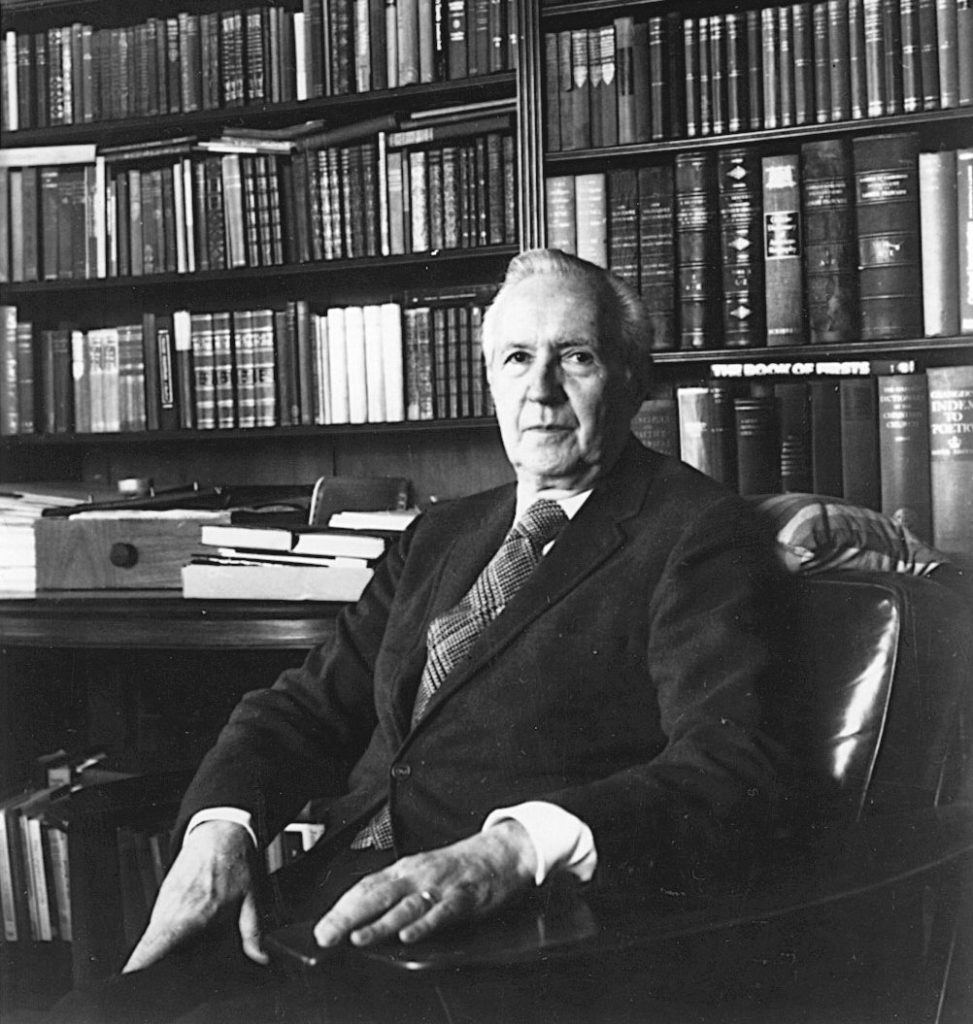

Jacques Barzun delivered this lecture half a century ago

Click here to read previously unpublished excerpts from a 1999 interview with Jacques Barzun.

Introduction

Charles Barzun and Matthew Barzun

The essay that follows was originally delivered as a lecture in 1969, but the two of us learned of its existence only in 2002. We were visiting our grandfather and his wife, Marguerite, at their home in San Antonio, Texas. After dinner, our grandfather offered us a CD on which was written in permanent magic marker, “Present-Day Thoughts on the Quality of Life (1969).” A stranger had sent it to him, but he had no memory of, or interest in, its contents. We were free to take it.

At the time of our visit, Jacques Barzun was 95 years old. He had been retired for more than 25 years from his post at Columbia University, where he had taught history for nearly 50 years and had served as provost for a decade. Though he had written dozens of books, his recently published magnum opus, From Dawn to Decadence, was earning him more national attention than he had received since the 1950s. His body was frail, but his mind was sharp. He continued to read and write for another decade until he died in October 2012, five weeks shy of his 105th birthday.

For each of us, our grandfather has been a guiding star in our lives and careers. But the Jacques Barzun we love and admire is not the famous historian and chronicler of the West’s decline, or the precise grammarian, or the iconographer of baseball, or even the man who knew everything. He was instead the lifelong humanist who, despite a traumatic childhood—indeed, because of that childhood—revered above all the “special quality in life” that can never be fully explained or defined but is no less real for it. That same reverence, as well as our grandfather’s humanism—one that insists upon the inseparability of feelings from thought—have fueled our own life’s interests: in the law, in diplomacy, in publishing, and in politics. It surprised neither of us when our grandfather told us years ago that, had he not become a historian, he would have entered the diplomatic corps.

Soon after our visit, we transcribed the lecture and sent it around to friends and family. Only years later did we learn that it had been given as part of a sesquicentennial symposium at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, entitled “Man and Life.” Although the university published its proceedings, it was a very small printing and, as a result, both the written and the audio versions have been very difficult to find. So when the lecture’s 50th anniversary was approaching, we reached out to The American Scholar about publishing a transcription of the audio version for the first time for a larger audience, with the thought that the questions it raises have special relevance today.

We did so, however, with some ambivalence. In today’s political climate, the lecture may be jarring, less for what it says than for what it does not. Although it conveys well our grandfather’s distinctive vision of the world, his observations of American society may seem so out of step with his own times as to be almost obtuse. During a century that witnessed two world wars, the Great Depression, the introduction of radio and television, the use of nuclear weapons, and the dismantling of Jim Crow, he insists that little of significance has changed in American life since the 1870s. At the end of a decade of riots, protests, and marches against racial apartheid and an intractable war, he notes the lack of political “Causes.” And a year after the assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr., he laments the lack of any true heroes. In short, in his preoccupation with the cultural malaise of the 1960s, he may seem to have been deaf to the political thunderclaps around him and blind to the injustices causing them.

But there’s an explanation for these opinions and omissions. It’s not that his privileged position as a white, male, Ivy League professor caused him to be out of touch. At Columbia, he was on the frontlines of those conflicts. No, it was something deeper and more personal. Our grandfather often spoke of how his childhood calm was shattered by World War I. He remembered vividly hearing the news that cousins, uncles, and teachers had been killed. He recalled seeing the maimed, shell-shocked, or gassed on the streets of Paris. When he began to talk of suicide, his parents took him out of school and sent him to the seashore, where he spent his days reading and reflecting. He later credited his reading of Hamlet as a 10-year-old with curing him of his suicidal thoughts.

Although his depression lifted, he once wrote, that experience “put an end to all innocent joys and assumptions … and caused a permanent muting of the spirit.” This early encounter with the senseless slaughter of war, albeit at one remove, must have numbed him a bit to the social upheavals and political conflicts he witnessed over the course of his life, including the particularly heated ones of the 1960s. Early on, it bred in him a historical sensibility—a feeling of detachment that prevented him from seeing every untoward event as menacing, every success or defeat as permanent, every opponent as a monster. So even when he wrote about horrors and calamities, his tone, as the commentator Arthur Krystal has put it, “is less that of someone appalled by what’s happening than of someone simply recording the ocean currents.”

This “permanent muting of the spirit” also meant that Jacques Barzun was not your typical grandfather, or father, for that matter. As grandchildren, we did not bounce on his knee. Although we and our sisters grew up calling him Grandpa, he later informed us that he had never liked that title and requested that we instead refer to him as Grandfather. Our father recounts how a comparable formality permeated his own interactions with his father, at least during those rare times when his father was not off working in his study.

But this is only a partial portrait of the man. Admittedly aloof and reserved in his dealings with others, our grandfather was also a romantic in the sense that he fervently defended the artists, poets, composers, and philosophers of the Romantic period. For Barzun, romanticism did not consist in the torrid exclamations of lovers or the ecstatic warbling of poets and spiritualists. The “Romanticists’ point,” he once said, “was in fact not an emotional point at all, but an intellectual point about the emotional life of man.” That point is that our emotional life is the source of our most creative and constructive powers, whether in the moral, aesthetic, or spiritual domain.

Barzun’s romanticism explains his concern in the lecture with the individual’s internal life or sense of self. The self, Barzun had observed, is “the primary one in determining the quality of life.” It is the sum total of the observations, discriminations, attractions, and repulsions, from the spiritual to the mundane, that orient a person in the world. It is what enables the individual to render the world meaningful.

But the self requires protection, which is where Barzun’s concern with formality and manners comes in. The creative energies that the romanticist prizes do not arise spontaneously; they develop only when the self has been properly guarded, nurtured, and cultivated. The function of a system of manners is thus to offer such protection, thereby preventing the self from becoming a “vending machine.” That is why he at once sympathizes with the hippies’ search for meaning yet doubts that free love will help them discover it. It is how he could remain a romantic in spirit and yet so formal in personal style.

Talk of nurturing and cultivating evokes images of farming, and that is intentional. Our grandfather cared above all about culture, which he saw as a process akin to the planting, toiling, and harvesting that agriculture entails. What is harvested are those creative and constructive energies on which our future depends. So when he complains about the breakdown of manners, he is voicing a concern about the eroding social conditions—the metaphorical soil—necessary for the cultivation of such energies.

Can a preoccupation with culture still be justified today? We think so, though we admit the burden seems heavy. Perhaps not since the decade in which he delivered the lecture has there been so much political conflict and uncertainty in our country. We seem to be living in one of those “drearier times” and “more anguished moments” about which Barzun warned us. Moreover, at a time when the conventional standards governing political life and debate seem to be disappearing as fast as the polar icecaps, it’s hard not to see talk of “culture” as peripheral and pointless. There are only politics and power.

But if Barzun is right, the opposite is true. Culture (in the descriptive sense) is what gives the shape, form, and quality to our lives. It consists of conscious and unconscious patterns of thought and behavior that channel and direct human energies. Thus, where there are political ruptures and social divisions, cultural pathologies must lie as well.

One such pathology that continues to afflict us all is our vacillating attitude about the sources of our own identity. On the one hand, we Americans tend to celebrate the self-made man or woman, the entrepreneur, the free agent. On the other hand, especially these days, we see an impulse to construct our identity by group or tribe, whether based on race, ethnicity, or political ideology. But our grandfather’s work reminds us that the forces that bind us together are expressed neither in Instagram feeds and Facebook profiles, nor in marches and protests. They instead take their form in our habits and manners—the way we think about, talk to, and deal with other people, particularly those whose concerns seem alien to our own. In other words, the virtues in demand are the essentially diplomatic ones that allow us to sustain multiple but meaningful human connections. For there is nothing older on the planet than political conflict, and no “solution” to it worth the cost.

True, it requires a kind of faith to believe that culture can be shifted through conscious effort and that such efforts may enable us to deal effectively with our social and political predicaments. But it is a faith our grandfather maintained for the better part of a century. And that may be his most important lesson for our present “anguished moment.”

Charles Barzun is a professor of law at the University of Virginia. Matthew Barzun is chair of Tortoise Media and former U.S. ambassador to Sweden and to the United Kingdom.

“Is Life Worth Living?”

Jacques Barzun

My purpose is chiefly to describe what is bothering a good many people today, rather than to go deeply into the causes of disquiet and unrest in the Western world, much less to offer remedies or advocate revolution. I take it for granted that we all know what we mean by “quality,” but the term “life” is not exactly a clear and distinct idea. It can stand for a number of things, and people in fact take it very differently. Some stress the value of life from the point of view of society—the need for talent, the opportunity for service. Others find the existence of another person satisfying—wife, child, lover, friend, and so on.

I think we have to start a little further back if we are to understand the feeling behind the question “Is life worth living?” Its root meaning, surely, is personal, subjective, solitary. There is a sense in which life is experienced, has always been experienced, and will continue to be experienced, by only one person: the living person. We have, to be sure, a vicarious, sociable knowledge that other people are alive, and that knowledge is both delightful and important. But only one person—yourself, myself—knows at first hand what life is.

Therefore, the question “Is life worth living?”—which has been asked through the ages—is a question that begins with the feeling attached to living by a person who is at the moment thinking about living, who knows what life is as no other person can know it and who knows whether he thinks it good. We have evidence right now on all our campuses, in all our periodicals, in all the great events characteristic of our time, that many people are saying, “My life is not of the right quality”; some say, “My life is not worth living. I want to remove myself from this society. I want nothing to do with its business and its institutions. I want to start life again on a new basis.” That is the meaning of being a hippie, of being a rebel, of being a certain kind of university student, of being a religious or philosophical critic.

A student of history such as I am might be tempted to call this feeling local and temporary and youthful, if it were not clear that the mood exists in many places throughout the world and that people who are no longer young support the views of the young, echo in their own hearts the objections, the complaints, and the rejection of life as we know it. So we are brought to consider what it is that the individual finds intolerable nowadays, or in other words, what general conditions detract from the quality of life. Obviously it is no longer enough for a person to be able to say to himself, “I am a good physician; I am an able lawyer; I deal in real estate better than my colleagues.” Brokerage, the law, and medicine seem at that level a mere rationalization of the physical urge to live. A rationalization, not a reason. This depreciation of one’s own value is connected with one’s awareness of people in large numbers. One says or thinks, “There are hundreds, thousands of physicians, lawyers, and real estate brokers who would serve society and supply its wants if I were not around.”

And in truth, the quality of one’s life resides in something immediately felt, not reasoned about—something that does not have to be sought by the indirect path of usefulness. I know that the whole tendency of our talk is the other way. We think that being useful, that being wanted, is inherently satisfying. We say so often enough. But I doubt it, in the light of what the new generations are doing and looking for. Our talk of service is not hypocritical, but it is a vain effort at reassuring ourselves.

So, where do we begin? We begin with the modern, industrial, and democratic society that we have known for the better part of 100 or 150 years. Its characteristics could be broken down into half a dozen groups. But I shall take up only a few indicative traits, habits, or attitudes to be looked at, rather than pretend to give you a complete survey.

The first characteristic we are to note is the vast increase of impersonality in the contacts we have with other persons. This is what generates the feeling of anonymity, of lack of self, of what has been called “alienation.” That last word has unfortunately been diverted from its original meaning until it covers nearly all our new troubles and new perceptions. But never mind. The individual is said to be alienated from himself and from society by the feeling that he is a mere unit, a cipher. He feels, moreover, that he has no power of either achievement or resistance in relation to the environment. He is manipulated, conditioned, or as we most often say, “pushed around.”

Undoubtedly, the present uprising against institutions—institutions as such, regardless of their innocence or merits—comes from the dim, dumb feeling that institutions are the agencies of manipulation. Students who say, for instance, that they do not find their curriculum “relevant” are really complaining that their courses are not something for them, but are a device for fitting them into the great organizations that run the world. The suspicion is of that outside world, and it destroys faith in everything inside, down to the roots of being. Impersonal contacts do not occur from choice, or as the result of individual traits. They are forced on us by the nature, and even more by the number, of our connections with the big world. It is a vast industrial process, and we are processed by it.

But with the process goes something that few people consider or talk about: I mean the breakdown of manners. And I mean in turn by the breakdown of manners both the indifference to others and the obsession with casualness, with informality, which we keep stressing in all the arrangements that we make. One can clearly see that, at first, casualness was designed to counteract this very coldness and impersonality of industrial life. We were meant to get a taste of brotherly love from having ready access to other people, not stopping for bows and scrapes, and immediately using first names. But of course there are diminishing returns to the idea of cutting out manners, because when informality becomes uniform, it loses its value of modifying formality, of contrasting with impersonality.

Besides, the unconscious mind and the senses soon notice that if everyone has equal access to you on easy terms, he chips off bits of yourself for his own purposes and leaves you depleted. He breaks into your life at will, claims your attention, enlists your sympathy, and acts with the emotional selfishness of a child. In short, the façade that we used to think false and pompous was in fact a protection for the self. It was a value to the ego when someone bowed to you. When instead the stranger gives you a nudge in the ribs and says, “Hey buddy, give me a match, will you?” the ego is disregarded in fact and becomes negligible in theory. You have become a vending machine.

To sum up, industrial and democratic society has not generated its proper manners. This is not the time or place to invent a system of new manners and submit it to your judgment. But the subject is worth thinking about. Let me just prime the pump with one suggestion. In our modern life of mutual attrition, the basis of any new etiquette should be to avoid disgusting your neighbor. Contempt is one of the corrosives from which we suffer. And it is not the old contempt of arrogance, of superior ego toward inferior, or anything of that sort. It is the contempt of indifference and disgust. The contempt of thinking that the other person is an interchangeable part of the machine, as unimportant as oneself. I dwell on self and ego because it—or they—are the place where one feels most directly and intimately the quality of life, and when in turn this quality is lacking, one hears of identity crises and other forms of the breakdown of the will to live.

A second fundamental loss is what I might call the disappearance of work. By work I do not mean busyness, nor effort, nor struggling. I do not mean the rat race of the executive life from which we all suffer. I mean work in the simple sense of tackling a job of some interest, overcoming its difficulties, known or unknown, and seeing at last a finished product—finding one’s powers, as it were, objectified in whatever it is, a chair made with one’s own hands, a new work of art or craftsmanship, any accomplishment in the realm of human affairs, even if it is only cleaning a house or painting a fence.

Everybody nowadays speaks of their professional and social energies as continually hemmed in by frustration. That is the prevailing word. Well, frustration means repeated nonaccomplishment, nonwork: pushing the rock up the hill and having it come down again. And nonaccomplishment is one of the most debilitating and despair-making experiences of life. It arises from the division of labor and the replacement of real work by abstract operations. From the concrete business of making a stone axe or turning a pot on a wheel, we have made our livelihood depend on answering the memorandum, picking up the phone, and trying forever to get somebody else to do something. It is a withdrawal from a part of reality, and that is what is so damaging to people, because they still possess great energies; they are still moved by the feeling that they must give themselves to some task, and they never see any task done.

The consequences are far-reaching: one of the causes, certainly, of modern dissatisfaction with the state; one of the causes of the strong belief that politics is to be despised, that no city is worth our patriotism, loyalty, or love. All these patterns of hate come from the feeling that nothing can get done, that nothing is done.

Take, for example, air and water pollution. We know a great deal about its physical and chemical conditions and remedies. We are all agreed that it is bad. There is no party or league that I know of which is in favor of air pollution. There is no rival school of thought as on other topics. And yet, we can do nothing about it. The more we know the less we seem able to perform. This is partly a result of democratic participation, which works so slowly. But it is also the result of our new attitudes toward work, or nonwork. We are too familiar with paper and not enough with reality. We are enmeshed in systems of words and ideas and statistics, which are often but the fantasies that active brains, not taken up with real work, devise in their moments of fatigue and self-contempt.

A third destroyer of the quality of life is democratic competition and envy. What I am about to say under this head, incidentally, does not mean that we should abandon democracy. What it means is that we should recognize how equality generates envy and pointless competition. Competition, in the sense of outdoing your neighbor in some productive effort, has long since vanished, as I have shown. But there remains, stronger than ever, the competition that calls for justifying one’s existence over and over again. If we could measure the amount of talk among us that comes down to self-praise, beginning with individuals and going on to institutions—colleges and universities particularly—we should be aghast. Every little group, every momentary or permanent establishment feels the need to continually say what good things it is doing, how indispensable it is to the universe, and how distinctive—indeed unique—it is. Others are doing the same thing and paying no attention to anyone else.

This apprehension, this envy, this self-justification combine to encourage deplorable habits. In the first place, they reinforce what might be called biased self-analysis: “What am I doing here? Why am I doing it? What are my objectives? Am I up to date? Have I done better in the first six months of this year than the first six months of the year before?” This familiar self-consciousness is just as bad as the intolerable shyness of an adolescent standing on one foot and then on the other, putting his fingers in his mouth, and not knowing whether he wants to be there or underground.

Self-consciousness is, again, an enemy of reality. For it means that we are always thinking about ourselves—our place in the group, our place in the world, or in the whole line of endeavor that we happen to pursue. We are not living, we are spectators at our own life, wondering at our ranking, our rating, our popularity. It comes out in reverse in our conversation. There we have to express self-depreciation, which is the offprint of the self-praise that we make public. The two are the two halves of what would be a real life lived: forgetful of self and possibly enjoyable.

Next, one could say that a certain quality has gone out of life because of the limitations that have been put on life’s goals by a secular culture. We have only a vague recollection of loftier goals because relatively few people are left who remember or who experienced the best of the old religious feelings. I do not mean that people are no longer religious or incapable of belief in transcendent reality. What I say is that it is extremely hard to sustain such beliefs and feelings in a world that quietly asserts that they are less than moonshine. And by extension, even apart from religious ideas, all heroism, greatness, nobility are discounted. Life is limited to what we can do in the span and the spot of present social utility. Now, it’s no doubt possible to be for a while an enthusiastic young seller of vacuum cleaners. But the time comes when the thought occurs, “Is this what the planet and its teeming millions must devote themselves to: selling one another soap and vacuum cleaners? Must I, with only this instant of time at my disposal, this life of mine, the only life, Life with a capital L, spend it ringing doorbells and telling prepared modifications of the truth about a gadget?”

This self-questioning is even more noticeable in the middle-aged than in the young. The crisis of the 50th year among those in business is getting to be a familiar fact. Suddenly comes the revelation, “I have made enough money to live on for the rest of my life. I now want to devote myself to something else—some good purpose that does not pay in cash.” And they gravitate toward the hospitals, the universities, the charitable institutions, with the hope that they can be translated to a different realm where every act will be self-justifying, where the stuff dealt with will not merely serve bodily needs but will somehow accumulate credit in a heaven not at all religious or transcendent but simply independent and spiritual. And these same people are terribly disappointed when they are told that if they want to work for the university or the charity organization, they will be given a desk, a telephone, and a secretary in order to start the same old routine with different words, equally mendacious. The one difference will be the much smaller salary check.

I have spoken of the distrust of greatness and heroism. We owe that particular loss to the working out of the principle of democratic equality. If everyone is like everybody else, nobody may be deemed superior, and nobody should try to be. Ambition in the old sense is dangerous and destructive; we cannot afford great men, powerful leaders. We distrust power. The term elite is a reproach. And meritocracy is a new word that carries the overtones of injustice. Besides, where would one find the worshippers of great talent? Everyone is concerned with his own dwindling self, trying to nurture it, and therefore very touchy. Out of mutual considerateness, everybody agrees that we should all be human—that is to say, harmlessly average. The one outlet for self-assertion is through membership in some going concern that deserves the name of good or great or permanent. In other words, ambition is socialized, and hence limited, which for good or ill means life is limited.

There is of course another possibility. One of the great goals for high talents in the past was that of the meditative life. But this too we have made extremely difficult by denying it sanctuaries. The monasteries of the Middle Ages are gone, and a secular place where until recently meditation was possible, the university, has turned worldly and embattled. Its members are too frequently found in jet planes and international hotels, which is not a monastic experience. What the sanctuary permitted, of course, was a reversal of values that comes out pretty much the same as ambition. If you kill a great public ambition by your own desire and devote the released energies to contemplation, to study, to the achieving of inner peace, you’re attempting a great piece of work. Becoming a saint or a scholar is no less strenuous than becoming Napoleon or Genghis Khan or Lincoln. I am not so bloodthirsty as to want only great leaders in the military, but now we tolerate no exceptions. Our nuns and monks are in secular attire, busy and traveling and conferring under the sway of the social gospel. The amount of true meditation that goes on anywhere would hardly fill a paper cup, which is one of the reasons why we have so few new ideas. New ideas are the products of leisure, meditation, reflection. We are all journalists: we work for the day. And the great works of philosophy or art, which in the past came from at least a partial sheltering, are hardly possible now. And their absence, in the end, affects adversely the quality of life for everybody.

The last great limitation under which we labor is that we are unmistakably at the close of an era—the era that began around 1500 with what we call the Renaissance and which developed all the forms of art, all the forms of social thought, philosophy, and political organization by which we still profess to live. These forms, ideas, and institutions were in many cases Causes with a capital C. People, for example, fought for political liberty and were inspirited by the very struggle. Now the theory of liberty has been so widely accepted that there is nothing to fight about. Nobody believes in slavery; nobody believes in discriminating against women or depriving children of their rights. There is no emancipation to be fought for. To be sure, there is the practical task of carrying out the common belief in liberty, but that is dull work, not a Cause.

Similarly, in the arts it used to be a Cause to fight against conventional art, academic art, or else the art of the previous period—and, by producing new masterpieces, to show that there is an original way to paint or to write or to compose. Now there is no fight left. There are no philistines left to knock over the head with epigrams and great works. Anybody can get a one-man show. Anybody can do anything, on canvas or without it. Pick up a few things from the junkyard, assemble them, and you may be the new wave. There is no resistance and no need of courage.

This lack of Causes is perhaps a subhead under the absence of work. In both, the desire to lose oneself in some effort which has a goal transcending the self and which yet will leave a mark is balked, denied. Or, to put it another way, there is no stage or platform where an idea or a person can be seen and judged, glorified or damned. The dramatic quality of life, in short, has fled, leaving only the sense of futility, which inhabits our young and many of our older inhabitants of the suburbs—people seemingly so complacent and so satisfied.

To top it all, we suffer from the illusion of change, which should contradict everything I have said. That illusion is a destructive fantasy. Count the instances when you hear or read that the world is changing so fast that that is why we feel so uncomfortable. It is a cliché, an obsession. And a great error. Little that is fundamental has changed since 1890 or 1870. I mean in the relationships of individuals, relationships of men to machines, of men to their beliefs and their fears. What has changed is the surface of life—interesting, and not negligible. We go faster in airplanes than in trains, and also slower in automobiles than on foot if we are in a city. These are captivating variations on the theme of locomotion. But the underlying forces and their effects, the things that make up the quality of life, have not changed since the latter days of Thomas Carlyle or John Ruskin. They, and others with clear minds, described and predicted our misery. It was Ruskin who first pointed out that the conditions of modern work would induce self-contempt. It was Carlyle who foresaw the paralysis of social action. The bulk of their contemporaries may not have known what they meant; we do now.

To these evils, we bring remedies of various kinds, most of which tend to worsen the disease. They try to act by removing further qualities from life because they all partake of the idea of engineering. I mean engineering in the bad sense. The supposition is that what we face is a problem to be solved; and it is a foolish supposition. Human affairs rarely contain problems with solutions. They contain predicaments and difficulties, which is a very different thing. The sociological solutions propose to remove problems by finding out the state of fact, the motives at work, and making policies to fit. But of course, none of these elements stay put; it is like walking up a hill of sand.

Then we have the genetic remedy: we have the gene optimists who think that they can manipulate our genetic structure and produce ideal men, or at least better men, and even, some say, duplicate men—the exact facsimile of Einstein or Rip Van Winkle. The only limits here are in the imagination of the manipulators, who do not as yet seem to know a great deal about human beings in society. A rival nostrum is the psychiatric remedy: let us gather in friendly groups and tell each other our troubles. And by a kind of washing of our dirty feelings in the same tub, we shall all come out whiter and purer. Then there is the politico-economic remedy, in some ways very practical, yet it runs into the greatest difficulties. The conception of the Great Society has nothing intrinsically against it, except the natural resistance to forming new habits and the natural tendency towards waste, stupidity, and corruption.

An equally natural disgust with this spectacle brings us to the attitudes that I cited at the outset as giving our subject immediate importance, namely the retreat of many young people into a neoprimitivism—religious, in some cases, and generally humanitarian. Like primitive Christianity, this outlook is sustained by the feeling of kinship and often associated with sexual license, which is felt as the re-creation of a social bond. Some devotees go through this phase very quickly to reach the neoprimitivism through chemistry—I mean drugs, which are said to tap a lower level of consciousness and regain union in that organic, anti-intellectual way. In each of these remedies, something is given up for the sake of regaining a hold on the lost current of the will to live. The choice is: the life of impulse and self-will as against the life of reason and civility.

Such are some of the conditions that appear to make or that are said to make the quality of life evanescent. They are enough to suggest the likelihood that we are in a period of well-nigh total dissolution, and that before the wellsprings of a tolerable existence are tapped afresh, we shall go through even drearier times and more anguished moments. What the future will be is not the business of a historian to say. But whether the future lies with or without industry, with or without democracy, with or without science and technology, it is at least conceivable that the future will be without them, either through catastrophe or willful rejection. No matter. What is certain is that the desire not for life alone, not for brutish life, but for a special quality in life will not cease, even for the last shivering inhabitant of a devastated planet. That desire is planted deep, and it seeks its fulfillment, which is what makes humanity other than animal.

Click here to read previously unpublished excerpts from a 1999 interview with Jacques Barzun.