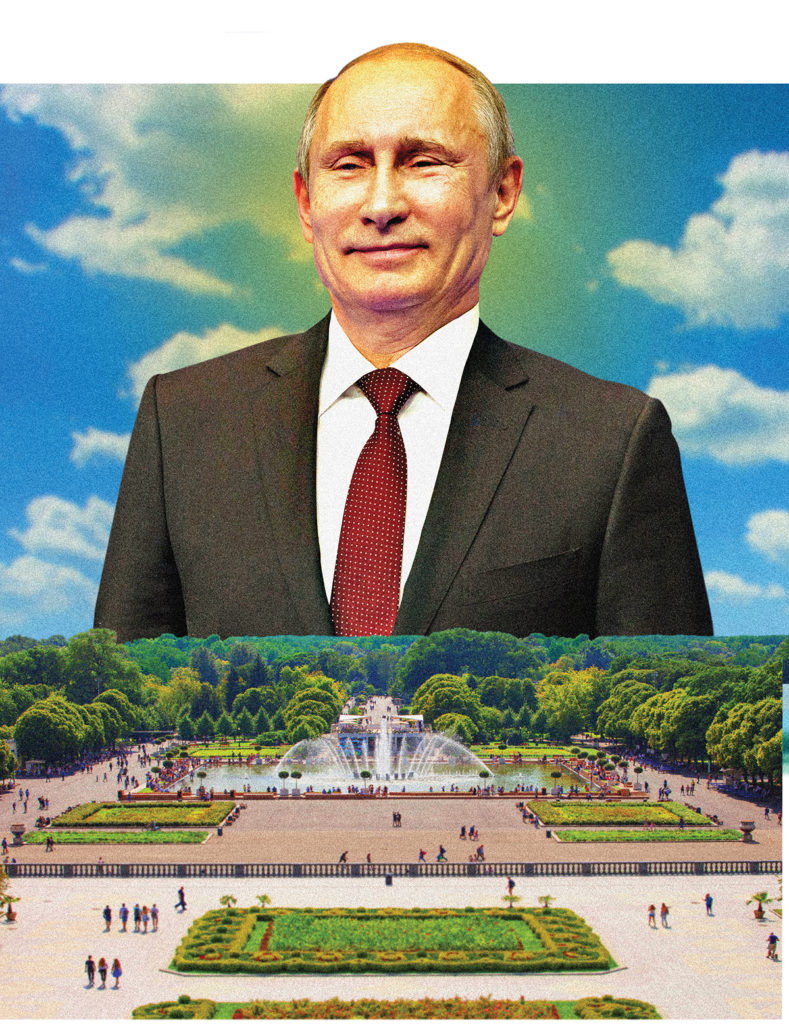

Putin’s Potemkin Paradise

The troubling appeal of Russia’s blend of political repression and bourgeois comfort

The travel writer Paul Theroux rode the Trans-Siberian Railway in the 1970s and again 13 years later, as a prelude to a trip to China documented in Riding the Iron Rooster. “Russia had changed in many ways,” he wrote, “and most of those changes were improvements.” Drunks no longer terrorized the dining car. The provodniks who attended the compartments now gave a damn. But there was one sure sign that the Soviet system would fail anyway: on the railway platforms, Theroux wrote, strangers still accosted him and offered to trade for his Western clothes. “Perhaps it was only my imagination,” he mused, “but it seemed to me that there was something fundamentally wrong with a country whose citizens asked to buy your underwear.”

I first visited Russia 12 years after Theroux’s second trip, and by then the street value of foreigners’ undies had declined to less than zero. Capitalism and freedom won, I suppose—and approximately in the way that I, as an American schoolchild in the 1980s and ’90s, was taught it would. No Russian, I learned, would prefer a system that was both morally inferior (because it oppressed its citizens politically) and economically inferior (because it oppressed its citizens materially). These were the days when Russians would line up for hours to taste a french fry in Moscow’s first McDonald’s. My teachers never explained whether both forms of oppression were necessary to bring the Evil Empire to its knees. Lucky for us, the Soviets had both. That is why the Soviet Union simply wound down its affairs, like RadioShack or Montgomery Ward, and closed up shop.

On that trip, I crossed Russia from Vladivostok to Moscow, and signs of the country’s incomplete adoption of Western capitalist-consumerist ways still abounded. Prostitutes would call my hotel rooms, dialing numbers randomly from the switchboard to see which guests were bored and alone. The dining cars rarely had anyone in them because the food was monotonous and gross. I shared a compartment with soldiers from the Far East, headed to the North Caucasus to fight in the Second Chechen War. Together we ate instant noodles and drank vodka. They spent whole days doing nothing but listlessly browsing porno mags and filling in crosswords. Once, I smelled something wonderful from the dining car, but when I entered, the cook raised a finger before I could speak. “Not for you,” he said in English. It was his own dinner—sausages and a thick soup. On the platforms, old women sold oily potato-based foods in plastic bags so gossamer-thin that I thought they might dissolve, like the casing of a Tide Pod.

The march toward parity with Western lifestyles had nevertheless taken a few steps forward. They may have been goose steps: no one imagined that the new political freedoms resembled those in the West. But Russians at least had a chance to buy the goods they were once denied, and even in small Siberian cities one could see people whose lives were, like mine, flagrantly bourgeois.

Now Russia poses a question opposite the one posed in Theroux’s imagination: Can any country that clothes its citizens and improves their standard of living be all that bad? In a deep moral sense, the answer is yes. In any other context, the evils of Vladimir Putin’s Russia would require no enumeration. But before considering all the good things Putin has done, one should take care to specify the evils. Putin is a thief—by some accounts the richest man in the world, which is to say the richest person who has ever lived. He is a murderer. Those who challenge his rule or defect from their loyalty to him die in distinctive and outré ways that reflect the participation of the Russian state. The most famous of these is Alexander Litvinenko, the former Federal Security Service (FSB) agent who defected to the United Kingdom and drank tea laced with polonium-210, setting off a miniature Chernobyl in his own digestive system that killed him three weeks later.

Then there is Alexei Navalny, the 44-year-old leader of the Russian opposition. Few people on earth would have a harder time getting a life insurance policy. Massive evidence supports Navalny’s contention that, last August in the Siberian city of Tomsk, Putin’s FSB poisoned him by applying the military-grade nerve agent Novichok to his underpants. (No one has yet offered to buy them.) He nearly died when symptoms appeared on a commercial flight. The flight landed in Omsk. Navalny was airlifted to Germany and recovered. He returned to Russia in January to challenge Putin and demand transparency in government and reduction in corruption. Russian authorities arrested him almost immediately, and unprecedented protests broke out in his support. Navalny is, at this point, daring the Nobel Prize people not to recognize him, in the unlikely event that he survives.

But here is the catch. The twin sources of First World superiority during the Cold War were moral and economic, and though the moral edge appears fairly sharp (say what you will about political leaders in the United States and Western Europe; some may aspire to be like Putin, but because they are bunglers and kept in check by other aspects of their government, none have come close to succeeding), the economic one is duller than you think. And for a certain class—corresponding roughly to those bourgeois types I saw 20 years ago, beginning to prosper in Siberia—it may not exist at all. If you believe the Cold War was won because a society where you can buy denim jeans and eat Big Macs until you retch will inevitably vanquish one where pants are scarce and your diet is meager and beet- and cabbage-focused—then you should downgrade your confidence that the United States will be able to challenge Putin. Indeed, some would apply to any of several other authoritarians who have delivered order and bourgeois comfort, unaccompanied by the dignity that comes from not living at the dispensation of a sociopathic despot. American political and economic hegemony sounds like a great deal when the alternative is abject immiseration. But the Putin model focuses on economic growth, at a pace ranging from slow to gangbusters, accompanied by eternal illiberalism—a model with obvious appeal to tyrants around the world, and now a plausible alternative to Western democracies for some of their citizens as well.

In 2019, I entered Russia from Norway and transected the country from its northernmost major city of Murmansk to its southernmost, Derbent. This time I cheated by hopping between cities on low-budget airlines and resorting only briefly to trains. That was, all by itself, an indication of something: taking interminable train trips, where the boredom of the featureless taiga sets in after the first hour, is a pastime only for those whose time is worthless, and who are in effect waiting to die.

Murmansk should not exist. It is the world’s northernmost city of significant size—a place best understood not as a natural human settlement but as a polar base that has somehow gotten out of hand. The buildings are, like many Soviet-era structures, big and charmless, but here they have the excuse of being built in an environment where aesthetic consideration is a luxury—after all, there is no appreciable daylight in Murmansk for months at a time. Why bother with a fresh paint job when you spend most of the year rushing to get inside and warm up? Overlooking the city is Alyosha, a 116-foot statue, in the blocky Soviet style, of a Red Army soldier. From Alyosha’s feet you can see huge piles of coal in the port and a sooty haze in the air that leaves a residue on all those buildings. The defense of Murmansk in the Second World War saved the Soviet Union. Since the Soviet defeat of the Germans saved, in turn, the rest of the world, I could hardly begrudge Murmansk for being proud of its sacrifice. Alyosha fought for me. Nevertheless, the city felt even stranger and more inhuman for having a concrete giant with a submachine gun watching over it.

Murmansk is the ugliest city I have ever visited, but in other ways it is a cozy little paradise. In one of those wretched apartment blocks I rented a suite that included amenities like fast Internet, a washer and dryer, and a heated towel rack—nothing fancy, except when you consider that you are in one of the extremities of human civilization. And the city had everything I, with my American tastes, could want. The grocery stores were full. I ate a breakfast of toast with cream cheese and cheap caviar. Late one night, I tried to buy a sweet Abkhazian wine, and the babushka at the grocery store checkout scolded me: alcohol sales stopped an hour ago, she said. It was the first time I had ever been denied alcohol by a Russian, and it was hard not to take that as a sign of social improvement. (Russian life expectancy jumped by three years between 2000 and 2010, mostly because Russian men abandoned the nightly habit of drinking enough alcohol to anesthetize a bear.)

Perhaps it seems that I am damning Murmansk faintly. At the time it did not feel that way. Instead, my growing love for this city felt like faint damnation of my own home of New Haven, Connecticut—not a bad city, but when you consider its advantages over Murmansk, you begin to wonder how it is possible that there is any competition between the two. Their metro areas are about the same size. One has had centuries of peace to figure itself out. It has a fine university, and every year it enjoys a nine-month thaw. The other is cold and dark, barely existed a hundred years ago, was nearly wrecked by Hitler, then was continuously impoverished through another half century of communism. Still, Murmansk, not New Haven, has the better playgrounds, restaurants, and nightlife.

St. Petersburg and Moscow are, unlike Murmansk, showcase cities, built and maintained to strike awe in foreigners at their grandeur, and to inspire patriotism in Russian bumpkins who come to the metropolis and realize that their country is not desolate everywhere. Before being sent to a penal colony in February, Navalny gave a final oration in court, noting that “life is bearable in Moscow, but travel 100 kilometers in any direction and everything’s a mess.” These Potemkin metropolises nonetheless tricked me completely—and so did provincial capitals many hundreds of kilometers to the north and south.

St. Petersburg is on the banks of the Neva, which by convention we now call a river. In fact, its name is Finnish for bog. (Until 100 years ago, the local demotic language was Finnish.) St. Petersburg is a marvel of urban engineering. It has reclaimed dry land and built in its place a city to rival and surpass Paris in nearly every way that a Parisian might wish it to be judged. Its bakeries, restaurants, parks, arts, museums—every one of these meets Paris’s on its own terms. Some of the city’s triumphs are imitative. Peter the Great famously sent his best minds overseas to plunder the styles and technologies of more advanced European countries. But today, St. Petersburg continues to put up buildings that are not hideous, whereas for the past 50 years, France has been, at best, a custodian and restorer of the buildings erected by its ancestors.

Next to Moscow’s Gorky Park, New York’s Central Park feels like a relic of another century. Gorky Park contains huge playgrounds for kids, free yoga classes for parents, a contemporary art museum. When I visited, I saw families lounging on publicly maintained beanbags, the parents reading magazines (not porn, I think, but I gave them their privacy), and the kids running around and flopping in the grass nearby. The child-rearing advantages in Russia were the starkest of all its differences with the United States. In the latter, raising a child has become expensive and lonely, with the burdens falling directly on the shoulders of parents. In Russia, I witnessed servers at restaurants pick up the babies of strangers and bring them into the kitchen to play while the parents browsed their menus. Ordinary restaurants (not Chuck E. Cheese, but places where single adults might go on a date) kept toys, and sometimes marked off play areas—like IKEA, but everywhere. (Fear of liability makes these courtesies rare in the United States.) The greatest kid entertainment on earth is a Russian circus. Most American parents I know would happily forgo a substantial portion of their income for the ability to parent less fearfully and with more cooperation from the rest of society. In Russia, it seems, parents actually do so.

The largest city of the Northern Caucasus is Makhachkala, the capital of Dagestan—a Muslim-majority republic that contributed more Islamic State foreign fighters than anywhere else in Russia or any comparably sized Western country. Dagestan has a vaguely Middle Eastern or Central Asian terrain, with desert lowlands and mountains impregnable to conventional armies. In this context, and the context of Russian invasions going back to the days of Tolstoy’s Hadji Murad, the relationship between prosperity and political dissent felt especially curious. Many of the Islamic State’s followers went to Syria in search of not a richer material life but a richer spiritual one. (I noticed no overt jihadist sympathy in Dagestan, other than a taxi driver who was listening to an Arabic nasheed, a kind of Islamic a cappella popular among jihadists. He turned it off and denied everything when I asked him about it.) Maybe the reaction of the Islamic fighters to the new Russian wealth was to reject it, or at least to realize that emerging opportunities for money and leisure were false idols, and to choose bullet-pocked mud houses and war over supermarkets and cineplexes.

But for those who remained, the consumer comforts were as evident as anywhere else—probably more so, given that just 20 years ago the North Caucasus was the site of an exceptionally dirty war. Putin and his local partners had made their peace offering to the region clear: submit to being ruled as if by kings and we will bring you abundance. Or, if you prefer the way of your ancestors, fight us and get more of what they got.

I asked for travel advice from an Afghan warlord who was well connected in the region. He replied that all his friends were exiled, imprisoned, or dead. One of them had introduced him to a fine floral liqueur. I visited the vineyard and distillery that produced it using plants from the owner’s garden. The proprietor was delighted at my interest. That was my experience of Dagestan: not bombs and kidnapping, but a jeroboam of champagne and a shot of sweet, boozy liquid infused with rose petals.

There is a name, historically, for people like me, and if you know anything about the jargon of the Cold War, it has already occurred to you. The term is “useful idiot.” (Useful ? I’m just happy to be appreciated.) In the Soviet era, these were the Westerners who went overseas on Intourist packages and came back rhapsodizing about their night at the Bolshoi, the equality of the new Soviet man, and the Moscow subway’s chandeliers. What made these travelers idiots was their belief that they were seeing anything other than what their handlers wanted them to see, and that through that tiny window they had a vantage on the whole Soviet system. Useful idiocy survives in the accounts of the assorted weirdos who take state-sponsored tours of North Korea and Iran.

One difference between the cringy accounts of Soviet splendor and mine of contemporary Russia is that I believe these autocracies have achieved these gains not because of their tyrannical practices but in spite of them. And I find their success a source not of envy but of concern. To visit Moscow today is to be forced to contemplate whether America’s double advantage was real—and to perceive a new challenge. Would the Soviet Union have collapsed if its tyrannical system had somehow provided material well-being, and only our moral advantage remained? The experience provokes a question that the Cold War never raised but that looks increasingly like the central question of this century: What do we do if tyrants become competent? Fifty years ago, only a fanatical ideologue or an adventurer would choose to live in China or the Soviet Union. Now the choice is harder. Smaller examples abound elsewhere. The happiest, most serene, and most livable capital city in Africa is Kigali, Rwanda, a country ruled by a capable autocrat who has brought stability and rising incomes without even the pretense of liberalism. Saudi Arabia, for decades known to the world as a joyless pit of sand and an economic and religious monoculture, has announced that it intends to diversify and liberalize its economy and culture—without relaxing the absolutism of its monarchy. In Asia, the Chinese model is the more salient challenger to liberal democracy, and more and less menacing versions of it exist in Singapore (a technocratic dreamland where cost-benefit analysis has prioritized liberalism at the lowest level) and the Philippines, which is ruled by a Putinesque strongman. China is interning Uyghurs in concentration camps and destroying their culture. But my goodness, the economy is booming, and life outside the camps is getting better, as it has in China in general throughout the lifetimes of most Chinese.

In Russia, as elsewhere, it is tempting to wonder whether these rising standards might be, for political reform, the whole game. A friend who fled the Soviet Bloc in the 1980s tells me that his parents remember the middle Brezhnev years, when high oil prices made the Soviet Union temporarily rich, as the most depressing time of their lives because it seemed as though the system could go on forever. Goods were on the shelves, and no one remembered a better time, though they all remembered much worse ones. Now most Russians have only a vague recollection of the 1990s, when the Soviet state was plundered by criminals and the country deteriorated into an alcoholic wasteland. Russian GDP sextupled between 2000, when Putin took office, and 2010. (Russians call this decade zhirniye gody, “the Fat Years.” Growth has been slow since then, but the gains from that period do seem to have been permanent.) For many years, Putin enjoyed Saddam Hussein–like approval ratings. And don’t forget the free yoga classes. Who would jeopardize such a life for the chance to play human Whac-A-Mole with the billy clubs of Putin’s riot police?

The answer is tens of thousands of people, in Moscow alone. But these extraordinary numbers will not reach revolutionary magnitude without greater middle-class participation. “The winners of the Putin period have been the middle class of state civil servants,” Cornell political scientist Bryn Rosenfeld told me, citing teachers and doctors as examples. Protests before Navalny’s arrest in 2021, she said, were constrained by the absence of these groups. “They were destabilized by the post-Communist transitions of the 1990s, and now their salaries are being paid on time, and still rising.”

Others are more optimistic about reform. “We are all unconscious Marxists: we believe that revolutions start when economies are bad,” cautions Leon Aron, a Russian-born Putin critic at the American Enterprise Institute. “But that is not the case. Tocqueville pointed out that the hatred of the king was largest where the economy was growing at record speed.” That may explain Putin’s increasing suppression of dissent. As the standard of living has risen, some Russians have grown more conservative, but others have tasted material abundance and been emboldened to demand political rights as well. The masses may not be ready to rise up and risk their gains, but the minority that wants political change now requires a specific, and sometimes quite brutal, reaction.

A certain amount of Russia’s rise is still imaginary, just as it was in the Intourist days. The Moscow subway system is so beautiful and efficient that, in any American city, it would be closed to riders and converted into a museum. But more Russians still ride marshrutka-style minibuses, which are unglamorous, and no useful idiot ever sentimentalized one of them. The nicest food stores I visited were, not coincidentally, opposite the fortress that houses the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and in the Moscow flagship GUM department store—places most likely to be visited by outsiders. If Russia shines these locations until they sparkle, it can safely neglect everywhere else and still impress visitors. The large cities in Dagestan may seem more livable than New Haven, but some Dagestani villages looked plucked from the Afghan frontier.

The overall feeling, though, was of a country making progress, and doing so as a hedge against anyone who would call it to account for its moral failings. I had thought myself immune to this sort of thing. I knew the Russian government to be a malign influence, even if it can make its citizens and visitors comfortable. But I was won over, temporarily, by the bread and circuses. I mean that literally: I wished my own country had St. Petersburg’s bakeries or Moscow’s circus. It is hard to feel negative toward a country you envy, even in part. By the time I left, I knew I would have to deprogram myself out of my Putinophilia.

This is harder than it sounds. I flew back to the United States and landed at John F. Kennedy International Airport. Donald Trump’s inaugural speech, which described the “American carnage” he inherited from his predecessors, baffled me when I first heard it. But when you stand in the arrivals corridor of JFK, for a brief moment, it sounds like sober description. The shabbiness assaults your senses. The snaking queues to meet a glowering Customs and Border Patrol bureaucrat are the American equivalent of the Soviet breadline. The subway to Manhattan smells bad, and modest improvements cost billions of dollars. Compared with American cities, Moscow feels dynamic. New York, by contrast, feels like Paris or other cities of Old Europe, unable to afford innovation and instead intent on preserving former greatness.

Putin has invested in an illusion of prosperity. I would not mind a little more illusion of prosperity in American public spaces—or at least more appreciation of what these kinds of public extravagance can buy. Yes, they can buy acquiescence to great evil, but they can also buy self-respect of a positive kind, a sense of collective investment in a national project. The decrepitude of American public transportation, and of public spaces in general, from playgrounds to airports, reminds us that we grant the places where we meet each other only the lowest rank in our hierarchy of concern. We barely tolerate each other’s presence and feel fully ourselves only when alone.

For all the caviar and blini in the world, I would not trade my American passport for a Russian one, as long as the latter meant a truncheon in the face should I dissent from the government line. I am less confident that Russians themselves would be so intolerant of their own oppression. Theirs is a civilization of almost unsurpassed accomplishment in music, literature, and other arts—and of continuous misgovernment since the beginning of its recorded history. The truncheons are normal; the improvement in living standards is abnormal. If the streak of misgovernment shows even a faint sign of ending, do you risk what you have gained? Or do you put on some Shostakovich, stay home from the protests, and hope for incremental change?