The spring of 2020 brings the promise of death, especially to the already old. The coronavirus is racing from China to Europe to New York City, devouring hundreds of thousands of people and leaving countless others breathing to the merciless rhythm of machines. Public health authorities direct us to “shelter in place.”

I’m a step ahead, I think. On March 18, I happily moved to the Carol Woods retirement community in Chapel Hill, to a one-bedroom cottage brimming with sunlight. I felt like a freshman entering college again, awaiting new friends, Wednesday concerts, Thursday lectures, who knows. But shelter has turned into a cell. Instead of the cheerful din of the dining-room, meals arrive in cardboard containers with a knock on my cottage door. Before the pandemic, I delivered Meals on Wheels every Tuesday morning to eight or 10 clients who greeted me in pajamas or a wheelchair or in bed with a smile, a joke, “can’t complain,” “God bless,” while the TV flickered in their shaded rooms. With the 96-year-old novelist Daphne Athas, who wouldn’t wear her hearing aids, I held shouted conversations about the evils of Trump and the etymology of demagogue, her delight rereading War and Peace, or memories of her Greek immigrant father, while I placed the plastic dinner tray in her fridge and laid today’s banana beside yesterday’s brown banana. In February, alas, Daphne fell and was taken to rehab, where she has been denied visitors.

As am I. Shelter in place has become quarantine, derived from quaranta giornia, 40 days during which all ships arriving in Venice during the 15th-century plague were required to sit at anchor before passengers and crew could go ashore. Forty days and nights. Nine hundred and 60 hours. The long cottage silences are punctuated by shrill newscasters and the wavery voices of friends on cell phone and Zoom. And visits by Stuart, my beloved lady.

On our first date six years ago, I heard myself saying, totally out of the blue, “If we’re going to have any kind of relationship, Stuart, I need to know whether you like romantic comedies.” “I do,” she said. We’ve been living alone together ever since, laughing at our foibles. Before the pandemic, she joined me for evenings in my Carrboro apartment. Amid the quarantine, she furtively arrives in my cottage like a student sneaking in a dorm, although a six-foot-tall, blond, beautiful woman with a wide white hat can hardly count on furtiveness. She arrives at my door with romaine lettuce, cherry tomatoes, a ripe avocado, green onions, and a lemon, out of which she constructs an elaborate salad to accompany the Carol Woods chef’s variant of pasta and veggies that I sauté and spice back to life. Stuart takes food seriously. And friendships. Her incandescent smile warms everyone in her radius. Especially me.

By April, hospitals in New York City have become as crowded as rush-hour subways, with patients lying in hallways gasping for life. Then similar scenes appear in Los Angeles, Atlanta, the Midwest. Three-fourths of Americans are under lockdown. How much longer? We’ll enjoy normal life by Easter, Trump proclaims. Just wait and see.

In my cottage, quarantine gives rise to urgent existential questions that I long ago settled or shelved in a dusty corner of my brain. What is the point of surviving however long—months, years—imagining how my body and mind will deteriorate into nothingness? And how shall I get through the next two hours until dinner? I made a career teaching United States history, but I won’t find answers there. “Life becomes ideas,” the French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty wrote, “and the ideas return to life.” I’m desperate to breathe the air of lofty ideas.

One afternoon I come upon Wolfram Eilenberger’s Time of the Magicians: Wittgenstein, Benjamin, Cassirer, Heidegger, and the Decade that Reinvented Philosophy. Of the four philosophers in the title, whom I’ve heard of but never read, Heidegger seems the loftiest and maybe most helpful. There he is, alone in his hut a century ago, hammering out Sein und Zeit (Being and Time). Time I had all too much of, and not enough being to fill it with.

I knock on the door of his wood-shingled hut overlooking a green valley high up in the Black Forest. The man who greets me looks more like a peasant than a philosopher in his brown farmer’s jacket and knee-length breeches. He is small, lean, with tiny black eyes and a bow-shaped mustache above a pinched mouth. Not much to look at. But as his students at the University of Marburg can testify, Professor Heidegger is charismatic. When he enters the classroom, he carries an air of danger, ready to send the edifice of traditional philosophers crashing down upon their heads. “Thinking has come to life again” in his lectures, according to one student, Hannah Arendt. “Thinking as … a passion. Thinking and aliveness become one.” Heidegger dares to plunge into the momentous question unanswered since the Greeks 1,500 years ago: What is the meaning of “Being”?

Being is around us, he says. We have a preconceptual understanding of it—an everyday understanding. If I say, “There is a chair,” you ask no questions.

But think about that little verb is, Heidegger says. What does it mean to say anything is? There is a chair, and there is a cat, but where is Being with an uppercase B? Sein. Isness. Chairs and cats don’t worry about this question. Only humans do, so the answering takes off from you and me.

There’s a knock on my door and I drop the book, grateful to be called away from Heidegger’s boggling question. Inside the cardboard container I find goat cheese macaroni with steamed spinach and baked butternut squash. Soon Stuart arrives with a kiss, salad makings, and another episode of the mouse. Three nights she has put peanut butter in the Have-a-Heart trap and each morning no peanut butter, no mouse. “A political science professor,” she laments, “is outwitted by a mouse!”

“You’ve created a cushy welfare program,” I say.

“I consoled myself with a breakfast of poached egg with two asparagi, plus a slice of perfectly ripe avocado on toast.”

Oh Stuart, my beloved queen of the quotidian.

“And how are you getting along with Heidegger?” she says.

“Not well. He reminded me of a long-ago afternoon when I was a graduate student drinking coffee in Hannah Arendt’s New York apartment. I’d finagled the invitation through my mother, who’d been a friend of Hannah’s in Weimar Germany.”

“Wow. Lucky you.”

I shake my head. “All I remember is Arendt abruptly asking a question in German and me like an idiot, tongue-tied.”

“Failed the pop quiz, eh?” Stuart says, and we laugh together.

In the morning I resume where I had left that strangely intoxicating verbal music high in the Black Forest. “What is the meaning of: ‘es gibt’ (there is)?” Heidegger asks. “Again: the question is not whether es gibt chairs or tables, or houses or trees, or sonatas by Mozart or religious powers, but whether es gibt means anything whatsoever.” He pauses for a beat. “And what does anything whatsoever mean? Something universal—indeed, one might say, the most universal, that applies to every possible object.”

Heidegger is 29, delivering his very first lecture at the University of Freiburg, when he speaks those words. Three years later, in 1922, he spends eight days talking philosophy with his friend Karl Jaspers. Jaspers, a young psychologist and philosopher, has made a splash with his book about how people experience a sense of authenticity in the face of death. Germans are all too familiar with death. After four years of the Great War, one of every five German men is dead or maimed or suffering shell shock. Peace has brought hunger and angst along with political unrest: communists versus monarchists versus Nazis versus republicans. Worse, many Germans chew on a bitter fantasy about why they were defeated. The Kaiser’s omnipotent army, they believe, was stabbed in the back by Jews.

“I enjoyed our eight days of ‘symphilosophising,’ ” Heidegger exclaims to Jaspers. “A friendship came toward us, the growing certainty of engaging in a common struggle, sure of itself on both ‘sides’—all of that remains uncannily in my mind, just as the world and life are uncanny for the philosopher.”

But now he needs to be alone in his hut in the Black Forest. “When I have been meeting new people,” he explains to his wife, who has stayed home with their two sons in Marburg, “I notice I am essentially indifferent to them all—they walk past outside as if on the other side of the window. … The great calling to a transtemporal task must always also be a condemnation to solitude.”

That task is to decipher the ontological mystery of Being (Sein). It is a lonely task. Each of us, as an individual Dasein (“being there”), must undertake the work on his own. “Factual Dasein, whatever it is, is only ever the fully own, not the just-being of general humanity. In each case mine (Jemeiniges).”

This sounds like nonsense, I tell myself, as I close the book and walk to the kitchen. But give it time and an open mind, like when I first stepped into James Joyce’s Ulysses.

“A dollop of brie cheese did the trick,” Stuart jubilantly announces at dinner. “This morning I found the mouse in the trap and took him—or her? or them, as we’re supposed to say these days—to run free in the woods.”

I’m about to take salad out of the bowl when she says, “Wait! Before you mess it up, look how beautiful it is.”

I gaze at the undulant, gleaming landscape encircled by ceramic blue, and it is beautiful. “Thank you,” I murmur.

Heidegger is waiting for me in the morning. Dasein won’t find true knowledge of Being by taking courses in sociology or psychology, he explains. Search not in the ivory tower but in the everyday world. “This is the way in which everyday Dasein always is: when I open the door, for instance, I use the latch.” The path toward answers involves what Heidegger calls “projects.” Cut wood for the stove. Hammer nails to fix a floorboard. “The less we just stare at the hammer-Thing, and the more we seize hold of it and use it, the more primordial does our relationship to it become.” Handlichkeit. While you are employing the hammer, it acquires for you a “readiness-to-hand,” your particular Being.

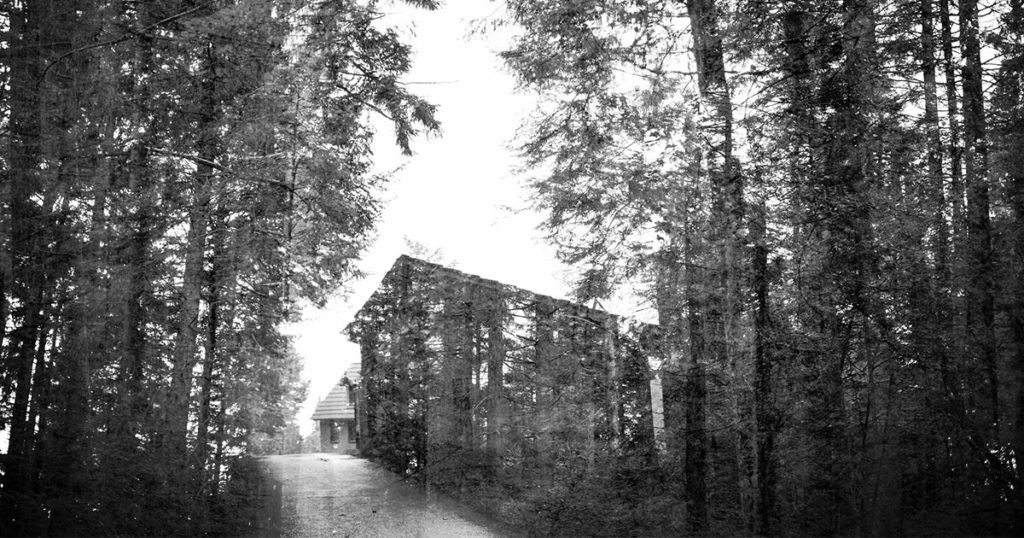

I find myself growing busy with projects. Or as the philosopher and novelist Iris Murdoch put it, I “inhabit” myself with projects. I make a loaf of herb and onion bread, enjoying the steady rhythm of kneading the dough with flour-dusted hands. Maybe this is how authenticity feels. Unable to take my camera to New York or Paris, where I shot the photographs that hang in FRANK Gallery and on my cottage walls in Chapel Hill, I improvise. I tear old prints into strips and combine them into collages. Voila! The familiar double-exposures are reborn into multilayered images that intrigue me all over again.

I lay out three of them on the coffee table. Stuart picks them up tenderly at the edges one at a time. “I’m not sure, is this supposed to be a child?” “Oh, I love this one.” “Sorry, this black blob is just … ” and she makes a face. Silently I protest against that “not-sure” and “blob,” but a few days later I recognize she’s right as usual.

Forty days have stretched to 60, 80, 120, interminable. New cases of Covid hit a record daily high. The virus rampages like invisible wolves. No, like swarms of bees. When I was stung 40 years ago, I spiraled helplessly down toward the darkness of extinction en route to the emergency room and the miracle of epinephrin. No, neither wolves nor bees—people, friends, and strangers, everyone is a possible killer with one cough of a microscopic droplet. Thursdays, senior discount day at the grocery store, I dash masked through the aisles grabbing bread, broccoli, yogurt, and bananas and return to my cottage breathless and sweaty.

One morning I wake up with pain throbbing on the right side of my jaw. The next morning it’s worse. Root canal? Cancer? I make an emergency appointment with my dentist. He and the hygienist, outfitted like astronauts, probe and X-ray. “Just a bruise,” he says, finally. “From clenching your jaw. This month we’ve had an unusual number of patients clenching, grinding, even cracking teeth.”

Stuart undertakes a project more daunting than salad. Her name has risen to the top of the Carol Woods waiting list, and a cottage has become available just down the path from mine. Now she has to outfit it. Week after week she struggles with countless quandaries about cabinet doors (maple or oak? light or dark?), countertops (quartz or granite?), towel bars (round or square?), and so on and so forth. She is making that cottage jemeineges, fully her own. Soon we’ll be even closer to each other.

I’m deep into reading At the Existentialist Café by Sarah Bakewell when the phone rings. It’s Daphne Athas’s nephew in California, who’s sorry to tell me she died two weeks earlier, alone. There will be some kind of memorial ceremony after the pandemic. I picture Daphne struggling to finish War and Peace in time. That evening I weep in the shelter of Stuart’s arms.

May. In Minneapolis, George Floyd slowly suffocates under the knee of a white policeman. “Black Lives Matter!” Back in the 1960s I marched and picketed and sang “We Shall Overcome” in the streets of Boston. Now, in solidarity with protesters across the country, I join a dozen white-haired residents at the front gate of Carol Woods. We stand for an hour, a few people hunched over their walkers, six feet apart in the shade, waving handwritten signs at passing cars.

The evening news makes us groan and shake our fists, but Stuart and I can’t help watching. As good citizens, it’s the least we can do. After dinner, though, we snuggle on the couch and watch another episode of Emily in Paris, a glitzy romp around the city we had eagerly arranged to visit for a week in May before Covid canceled us. Quel dommage.

The Weimar Republic is teetering on the brink of collapse. Inflation has soared into hyperinflation, with prices jumping 10-fold, a hundred-fold, within hours. The cost of a single egg equals the cost of one billion eggs before the war. People go shopping with a wheelbarrow of deutsche marks and stand in long lines to buy a loaf of bread. There are riots and looting. Communist brigades and nationalist Freikorps engage in daylong street battles in various cities. In a beer hall in Munich, Adolf Hitler, surrounded by Nazi Stormtroopers, calls on a crowd of 3,000 to “begin the advance against Berlin, that Babylon of Wickedness,” overthrow the government “of the November criminals,” and recreate “a Germany of power and greatness. …” They rush out to the Defense Ministry headquarters where soldiers fire on them, killing 16, and the mob disperses.

“I am driving to the cabin and very much look forward to the strong mountain air,” Heidegger writes Jaspers. “I don’t long for the company of professors. The farmers are much more pleasant and even more interesting.” The “simple folk” of the Black Forest have authenticity. “Eight days of wood-work, then writing again.”

Through the handling of its projects, individual Dasein seeks a personal relationship to Being (Sein). In this quest to know the essence, however, Dasein is beset by anxiety. “It is already deep night,” Heidegger reports. “The storm sweeps over the summits, the beams creak in the hut, life is pure, simple, and as big as the soul.” Instead of experiencing authentic Being, Dasein suffers a loss of meaning, emptiness, its own possible nothingness. In a word, death. This is the existentialist moment. “With death, Dasein stands before itself in its ownmost potentiality-for-Being.” We can live authentically if we choose to head resolutely toward our death.

Heidegger is working hard on his book but finds himself unexpectedly distracted. He has fallen in love with his brilliant, beautiful 19-year-old student Hannah Arendt, and she in turn is bowled over by her charismatic mentor. “The fact of the Other’s presence breaking into our life is more than our disposition can cope with,” he writes her. “I daydream about the young girl who, in a raincoat, her hat low over her quiet, large eyes, entered my office for the first time, and shortly and shyly gave a brief answer to each question. …” Nothing like it had ever happened to him, he exclaims. “To be in love is to be pressed into Existence.”

But there is also the mundane fact that he’s 35 years old, married with two children, so he insists they conduct their affair in secret. On the days he leaves a chalk symbol on a park bench, they meet in her attic room. When he lectures in other towns, she follows and waits for him two streetcar stops ahead. Obviously, she can’t work on her dissertation with him, so in the summer of 1926 she moves to Heidelberg and works with Karl Jaspers. “I will never be able to possess you,” Heidegger tells her, “but you will belong in my life henceforth, and may it grow with you.”

During the next two years they will continue to meet, furtively and passionately, but in retrospect Arendt’s departure marks a turning point. She has chosen “The Meaning of Love in St. Augustine” as her dissertation topic. While she employs Heidegger’s theoretical principles, she imitates Jaspers’ approach by analyzing relationships in practice. Neighborly love, for example. Whereas Heidegger is concerned with future existence, she’s concerned with past and present. Shortly after she earns her doctorate, their romantic relationship turns into a friendship.

During the summer of 1925, Heidegger writes 30 pages a day and completes his 450-page magnum opus. In Sein und Zeit the word love appears only once—in a footnote.

In addition to salad, Stuart arrives with her other favorite kind of project. It’s a 500-piece jigsaw puzzle, a mostly white and gray winter landscape that makes my heart sink. I have fun making collages, but fitting those tiny odd-shaped pieces together makes my head hurt. Worse, there is Stuart’s rule: proceed without looking at the picture on the box.

“Why must you make the task harder than it already is?” I complain.

“Why do you want to know exactly where you’re going? That takes away the excitement. And a lot of the pleasure.”

Stuart always avoids reading the jacket of a book. During a trailer at the movies, she closes her eyes and covers her ears. I consult reviews before deciding.

“After all,” she points out, “in real life we can’t know how things will turn out until they turn out.”

I nod my head. No need to say aloud what we’re thinking. Her husband died of a heart attack 11 years ago while running to catch a bus. Nine years ago, my 30-year marriage expired in divorce.

She strokes my arm and recites a verse by Garth Brooks.

Our lives are better left to chance.

I could have missed the pain but

I’d have had to miss the dance.

Fall. The virus rages out of control. Deaths spike. Trump tests positive. Three days after being hospitalized, he climbs the staircase to the White House portico, removes his mask, and raises one arm like an orange-haired Mussolini.

Biden becomes the Democratic presidential nominee.

“2020 will be the most INACCURATE & FRAUDULENT Election in history,” Trump tweets.

In the wake of publishing his book, Heidegger has acquired fame and a cult of admirers. At the end of every lecture, students burst into thunderous applause. In 1929, in the Alpine resort of Davos, he’s the star at a three-day gathering of illustrious European philosophers. Wearing his peasant garb, Heidegger confidently debates Ernst Cassirer, the elegantly dressed, Jewish proponent of Enlightenment humanism.

But now he makes a move that leaves me bewildered and horrified. Shortly after Hitler takes power, Heidegger agrees to be the rector of Freiburg University, which requires him to join the Nazi Party. In a hall adorned with Nazi banners, he delivers his inaugural address. “The essence of the German university,” he declares, “is the will to knowledge as the will to the historical spiritual mission of the German Volk as a Volk that know itself in its State.” As for students, “You can no longer be those who merely listen to lectures.” Commit yourselves “to make the sacrifices necessary to save the essence and to heighten the inner strength of our people in their State.” Do not let “ideas” govern your Being. “The Führer himself, and he alone, is the German reality and its law today and in the future. Heil Hitler!”

How do we understand Heidegger’s embrace of those loathsome principles? Pragmatic careerism plays a large part, as does political naiveté. But he has also stepped into the trap of his own philosophical ideas. Passages in his book about “Dasein finding uttermost possibility in giving itself up” to the universal take on grim meaning. His fascination with authentic German culture now harmonizes with Nazi racism. Heidegger is betraying existentialism. And as the Nazis strip Jews of legal rights, he goes on to betray colleagues and friends.

At first, Jaspers is spared, but, because he’s married to a Jewish woman, he eventually loses his university position. With sadness, Heidegger’s long-time, generous-minded friend—really his only friend—cuts off their relationship.

Arendt confronts Heidegger, but he sidesteps her questions and ducks responsibility. When she’s arrested and temporarily imprisoned by the Gestapo for writing about anti-Semitism, she flees to Prague, Paris, and finally New York. In her renowned books, she will employ Heideggerian ideas for un-Heideggerian purposes as she explains the origins of totalitarianism and advocates citizens’ responsibilities in a republic. For 17 years she will have no communication with him.

I too am done with Heidegger. My quest for lofty answers has come back to earth with a jolting lesson. Dasein’s lonely struggle for authentic Being produced allegiance to a group of men who murdered six million human beings. I need to attend to events taking place in the world around me.

November. Biden wins by seven million votes. Trump declares, “This was a RIGGED ELECTION! We won in a landslide.”

January 6. “We must stop the steal,” Trump tells his followers outside the White House. “If you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore. So we’re going to the Capitol.” Armed with baseball bats, flagpoles, hockey sticks, bear spray, and stun guns, the mob breaks into the Capitol building, beats policemen, ransacks offices, chants “Hang Mike Pence,” and shoots selfies.

As I watch all this on TV in my living room, I can’t stop my arms from shaking. This isn’t protest. It’s insurrection. It’s a putsch. For the first time in my life, I’m imagining a dictatorship in my country: Trump feeding his brutal appetite for power; the elaborate edifice of the republic crashing down upon us.

But the even more alarming fact, the chilling fact, is that most of those arrested in the Capitol don’t belong to extremist groups. They’re predominately middle-aged and middle class—shop owners, accountants, IT specialists. They’re ordinary men and women, representatives of the 74 million Americans who voted for Trump. They may be anyone, perhaps this man walking toward me in the grocery store aisle with his mask sagging on his chin.

The new year begins and the pandemic continues. Everyone at Carol Woods has been vaccinated. Stuart and I are giddy, dancing between freedom and anxiety. Shall we go to the beach? To a movie theater? Masked or unmasked? But surely we can deliver a year’s backlog of hugs to our two little granddaughters, can’t we?

In any event, I’m looking forward to teaching a seminar next month here at Carol Woods: outdoors under a big tent, 15 residents in person, unmasked. Sixty years I’ve been teaching, and I always feel excited, and, at memorable times, authentic. My lifelong “project.” I’ve chosen to go back to the 1920s—not to Weimar Germany, certainly not to Heidegger’s hut, but to the United States. It was a decade when Americans were divided, Klan vs. immigrants; fundamentalists vs. Darwinists; “wets” vs. Prohibitionists; race riots; Red Scare. Maybe we’ll gain some perspective on our own fractured era.

With romantic comedies and jigsaw puzzles, the outcome is predictable. Real life, on the other hand, acquires inevitability only when it recedes into history. Not knowing the future, we do the best we can in the meantime.

Stuart has taken ownership of her cottage and has been happily installing her belongings. This evening she will walk down the path with the makings of a salad. After dinner, we’ll work together on a new jigsaw puzzle. Then we’ll snuggle on the couch to watch Love, Actually for the umpteenth time.