Rabbit, Rabbit, Rabbit

“There was the rabbit lying in the middle of the road, legs limp but twitching before its head sagged and went still.”

It happened before the stop sign at the base of the hill, the steepest part of the road, an inevitability she should have anticipated when they moved in eight months ago. They’d come for her husband’s job, a faculty position at an elite liberal arts college in rural Pennsylvania, the kind of job he’d coveted when he started his history PhD at Berkeley and the kind of job she’d feared. He’d told her, Relax, there are colleges in every major city in America, and then he’d defended his dissertation and they were not in a major city, they were not even in a town, but on the outskirts of a tiny town where field ants marched through the kitchen until the first October frost and where swarms of carpenter bees drilled holes in the attic as soon as March crocuses appeared and where white-tailed deer dashed across the road all through winter, eyes gleaming in the dark. Her husband’s department chair had plowed straight into a buck this past January, the car totaled, the deer hobbling off into the snow to die. And now it was early May and the deer were breeding and she crept slowly down the hill, scanning the brush for fawns. She didn’t expect a rabbit. She’d never even seen one since they moved, just gray squirrels and striped chipmunks and the occasional firecracker-flash of a cardinal.

She’d just buckled her 20-month-old into his car seat for the five-minute drive she took every morning to the college-sponsored daycare before returning to an empty house and to the marketing job she was now working remotely. When she fastened the car seat, the baby had shouted tight! The baby was shouting new words every day, tree and apple and giraffe. She didn’t know if she could even call him a baby anymore. She hadn’t understood before having a child why parents never used years, why they’d say their child was “22 months old,” making her do the math, when they could have just said “two.” But now she understood, now she saw that each month was its own lifetime. The baby waved to her husband, whispered bye-bye. She pulled out of the driveway. She felt her foot on the brake down the hill, the stop sign visible ahead. Morning mist clouded the hills in the distance. For just one second, her eyes strayed from the road toward the rising sun spreading through the fog. And then she looked back and a brown flash magneted across the road and she stomped on the brakes and her purse sailed from the passenger seat to the floor. The crunch was sickening, a word she’d read in crime novels when a bone snapped or a neck broke. There was no other word. She heard her own screaming. The baby stayed silent, tiny shoes kicking against his car seat. Another car zipped through the intersection. At the stop sign, she peered into the rearview, hands shaking on the steering wheel, and there was the rabbit lying in the middle of the road, legs limp but twitching before its head sagged and went still.

The college billed itself as a close-knit community nestled in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, but there were no foothills, just soybean fields and livestock farms and more concentrated wealth in a two-mile radius than in the entire surrounding 11 counties. Ticks infested the grass. Last month, she’d spotted a nymph on her husband’s ear and grabbed it so fast, she nearly tore off the lobe. She scanned the baby every night in the bath, and he’d learned to parrot back: tick check. Gray heavied the sky all winter. Sometimes snow accumulated two feet in one night.

They’d closed on a three-bedroom house last June and flown from California to Pennsylvania in late July, bursts of goldenrod blooming through the surrounding woods when they moved in. An abandoned robin’s nest fell from the fireplace when she opened the flue. A family of field mice nibbled on the potatoes in the kitchen until pest control set traps. The baby’s room was across the hallway from their room upstairs, and the third bedroom downstairs became her home office. The window above her desk looked out on a field piled with snow all winter, the sky above a thin pancake of sludge. A content strategist, she managed the digital marketing and user navigation of a grocery-chain website. At the new-faculty welcome party, a literature professor asked about her work. When she heard herself say front-end strategy, the professor refilled his snifter and never came back. All year, she’d had the same conversation at the same parties with different professors refilling the same negronis and Sazeracs, professors whose faculty webpages were maintained by someone in college communications who did her exact job, maintaining outdated headshots they never replaced.

The corporation she worked for was based in the Bay Area. After she convinced her boss that telecommuting was entirely possible, the transition was easy if not for the crushing isolation. Her family lived in Wisconsin. None of her friends had settled anywhere nearby. Her husband’s family lived across the state line in Ohio, but Pennsylvania was wide. She dropped the baby off every morning. Her husband picked the baby up every afternoon on his way home from class, unless he had meetings or office hours or committee work, all of which had proliferated as the months progressed. And the hours in between, eight hours of silence, with only her computer and the faint crackle of the home’s forced air. It was the loneliest she’d ever been in her life.

After she dropped off the baby and returned up the hill, her hands still shaking, there was no rabbit in the road. There wasn’t even a bloodstain on the street. Maybe a red-tailed hawk had carried it away, or one of the turkey vultures she’d seen circling the hill since the snow had finally melted. She glanced at the passenger seat where her purse now lay, open and on its side.

Her husband’s car was still in the garage when she pulled into the driveway.

I hit a rabbit, she said when she walked into the living room.

He was dressed in a plaid shirt and khakis, sitting on the couch with his coffee. He scrolled through his phone and didn’t look up.

It happens, he said. Then he got up and left his mug on the fireplace mantel, a ring of residue, she knew, surely lining the wood.

She was still thinking about the rabbit as she breastfed the baby that evening, rocking in the chair that sidled against the nursery window, which looked out on the surrounding woods. She planned to nurse until he turned two. Their breastfeeding relationship had gone smoothly and largely unacknowledged for 19 whole months. But in the past few weeks, his language now fractaling out, he’d started tugging at her bra strap in public and shouting boob, what sounded more like boom.

She wondered if the rabbit was a mother. She imagined tiny pink babies nestled in the grass, eyes matted shut. She ran her finger along the curve of the baby’s ear, his still-small body tilted against hers, his pudgy hands worrying her bra strap as he nursed. She’d mentioned the rabbit again at dinner. Her husband looked up from his spaghetti for only a moment—they’d learned to eat their meals in five minutes, before the baby threw his food. It’s a rural place, he said. Roadkill is a fact of life here. Then the baby hurled a handful of noodles onto the floor, and she knew they’d never talk about the rabbit again.

All done boob, the baby said, and she lifted him from her lap. He’d long outgrown burping, but she rocked him and patted his back. He’d started waking at night, sometimes just a few minutes of crying before he settled himself back to sleep, sometimes longer until one of them soothed him. She held him close and thought of the rabbit thrashing in the street before going still, and the baby looked out the window over her shoulder and whispered moon, a glowing sickle rising above the trees.

In high school, just once, she hit a bird. She’d just gotten her license, she was speeding too fast with the new freedom of being 16, she was whipping around the bend of her best friend’s street when a robin flew too low against the wheel. She barely felt anything at all—she might have hit nothing if not for the confetti of feathers she saw strewn across the street when she pulled over and craned her neck toward the back window. She never told her friend. They opened Coke cans and watched five episodes of Friends. But that night, she lay awake and watched the ceiling of her bedroom and thought about the robin, its abandoned nest, the possibility of bright-blue eggs clustered in woven grass.

She didn’t know if her husband had ever hit an animal in nearly six years of marriage and another two of dating, but on one of their first outings back in California, a bright day on the beach in Alameda, they’d happened upon a purple shore crab, beached and overturned, its tan underbelly exposed, its thick claws waving desperately in the ocean air. Her husband picked up the crab delicately. He’d flipped over the pale body so the deep purple returned right side up, and then the crab skulked away toward a tide pool and disappeared into the shallow water.

As she strapped the baby into the car seat the next morning, she thought of that tenderness, that clear awareness in her husband’s hands of the crab’s fragility. She wasn’t sure where that tenderness had gone, if it was this place or if she was just so lonely here. The winter had been interminable. She hadn’t even seen a full summer, what her husband’s colleagues said could draw tourists from all over the world if they only knew, 12 whole weeks of lake swimming and long light and bonfire flames licking the night sky. But something had changed, in a way that was nearly impossible to pinpoint. They barely fought. He washed dishes, he whipped up weeknight dinners, he got down on all fours and play-wrestled the baby, who squealed with glee and shouted oh, dada! but she noticed the way he told his colleagues that he was from the Pittsburgh area when in fact he was from Youngstown, the deepest point of the Rust Belt, his father a steel-mill worker and his mother a retail clerk. Long before California, he’d put himself through community college, now absent from his CV, those two years replaced by all four at Ohio State and then straight on to Berkeley.

She clicked the seatbelt into place. The baby shouted tight! Her husband waved from the entryway and closed the door. And then she pulled out of the driveway and crept down the hill and thought about the rabbit and the red-tailed hawk that had surely carried it away and she still could not stop the car when another rabbit lurched from the same bushes and sank beneath the tires.

Her purse, this time, lay still on the passenger seat. She’d been prepared this morning, even if there was no logical reason to be prepared. But she heard herself scream. The baby waved his small fists in the rearview mirror. A lair of rabbits, all nesting in the same spot on the same street.

When she arrived at the daycare center, she led the baby through the hallways to the small classroom for 18-to-24-month-olds. Two babies toddled to the doorway and peered at her. The baby’s teacher took his tiny backpack.

Are rabbits a problem here in spring? she asked.

A faint wrinkle dimpled the teacher’s forehead. A problem?

She telescoped out of her body, a bird’s-eye view. She realized how absurd she sounded. She knelt to the ground and gave the baby a hug. Have a good day, she whispered into his hair.

When she drove back up the hill, there was again no rabbit anywhere in the street. No flattened fur, no bloodstain, no evidence that she’d hit anything at all. When she parked in the garage and found her husband sitting at the kitchen table staring into his phone, she sat down in the chair across from him.

I hit another rabbit, she said.

He laughed. He didn’t look up.

Women drivers, he joked, a joke he’d never made in his life. Are you sure you should be driving?

That evening, a faculty cocktail party. Graduation weekend. She distracted herself from thinking about the rabbit by looking up drink recipes and knowing the difference between a Paloma and a Verano. Private planes had circled all day over the tiny airport built specifically for the college, what seemed mundane now but had shocked her back in August when small jet after small jet flew in for move-in weekend. The graduation ceremony would be the following morning, preceded by this evening’s senior-class tradition of setting paper boats afloat at sunset on the campus lake and then meandering over to an enormous canopy on the quad where parents and faculty mingled with increasingly drunk students and a jazz band played before tables of hors d’oeuvres and desserts.

The baby was already asleep when the babysitter arrived. He hadn’t woken up in the night at all this week. They were five minutes away. She watched 300 boats skim across the lake and heard the parents sigh and kept it to herself that this looked nothing like a picture-perfect moment but like an armada, a tiny fleet preparing for war.

Beneath the canopy, a mojito in her hands, she stood beside her husband as he introduced himself to the parents of one of his graduating seniors, a tall kid in boat shoes with a mop of hair who had a job in finance lined up that, she suspected, would bring in more than her and her husband’s salaries combined. He was one of our best this year, her husband gushed, and the father beamed, even though she knew this kid had turned in his thesis three days late. She wandered over to the cheese table. She speared blocks of Gouda and Gruyère with a tiny fork. A recently hired music professor sidled up and loaded a small porcelain plate with fruit.

Well, we made it, he said. One year down and in the books.

One year down, she repeated, though she hated when her husband’s colleagues roped her in like this, as if everyone in town orbited around the sun of the college calendar.

Summer plans? he asked.

Not yet. We’ll probably stick around here and work on the house. You?

We’re heading to my parents’ place in Maine, he said. By we she knew he meant him and his fiancée, a quiet woman with dishwater hair who also had a doctorate but had trailed him here with an adjunct position for the year. By my parents’ place in Maine he meant their second home, which she knew had been in the family for generations.

That sounds nice, she said. Then her husband was beside her, filling his own tiny plate with an absurd amount of Ritz crackers.

The music professor slapped her husband’s back. Your wife was just telling me you’re working on the house this summer. Need any contractor recommendations? We just remodeled our bathroom, and I know a few guys.

She looked at her husband. His father had taught him how to fix a leaking pipe, install a hot water heater, build a back-yard deck. The one thing he’d complained about throughout this incessant year was that even though his colleagues play-acted at homesteading in this rural place, all of them still knew a guy, someone they paid to mow their lawn or plow their snow or clean their house.

Her husband shoved a cracker in his mouth. For now, we might just start a back-yard garden. Maybe take a trip or two. Maybe visit her family in Wisconsin or see my parents.

Where are they again? the music professor asked.

Just outside of Pittsburgh, her husband said, and she wanted to scream high above the drowning sound of the brass band.

She stayed home with the baby through the weekend while her husband attended graduation. He showed up in his Berkeley cap and gown and took celebratory snapshots in the midmorning sun with other new faculty, a scroll of group photos on Instagram hashtagged #firstyeardown and #wedidit, as if they themselves had graduated. The baby pressed his face to the kitchen window and shouted plane as private jet after private jet took off. And now her husband was on summer vacation, which meant he’d be home all day while she worked but they’d keep the same schedule. She would drop off the baby in the morning, he would pick up in the afternoon.

She anticipated a heavy week, an excess of virtual meetings mapping the user experience of the grocery site’s digital platform. Her husband would build raised beds, he would scatter potting soil, he would weed-whack just outside her office window. She said nothing at breakfast about the drive to daycare, the pit of fear growing in her stomach when she imagined approaching the stop sign. It couldn’t happen three times. Her husband sipped his coffee. The baby picked at his Cheerios. After she dressed him in tiny shorts and a tiny shirt, she buckled him into the car seat and set off down the hill.

They’d driven down the hill all weekend, to the cocktail party and to the post-graduation luncheon and to the grocery store, and there’d been nothing, no rabbits, no sign of movement in the bushes. But as she braked down the street, inching toward the stop sign, a rabbit rocketed from the roadside wildflowers and the car rattled over its soft body with a definitive thump. She barely reacted, only glanced in the rearview mirror at the flattened fur in the center of the street. But she felt her fingers tremble against the steering wheel as the baby whispered oh no.

When she led the baby into his classroom, one of the other parents was hugging her daughter goodbye, an English professor whose child was a few months older than her baby and with whom she’d tried to organize playdates that never quite stuck. They saw each other at cocktail parties. The professor had been writing some journal article all year about the problematic worldview of The Great Gatsby.

Happy start to summer! the professor said, and she bristled again at this roping in, as if her own week and entire summer weren’t filled with meetings.

Any big plans? she asked anyway.

The woman shook her head. Just writing. It’s so hard to get any research done any other time of year. How about you all?

Just working. She thought about the mulch, the potting soil, the weed-whacker. And planting a garden.

The woman’s face lit up. Did you see that big summer activity feature in the Times parenting section? We’re definitely making the strawberry-mint-yogurt pops.

She said she’d look it up, this foreign language of podcasts and articles floating in the ether of faculty parties. She’d already burned three of her four free articles this month.

When she arrived home, the rabbit nowhere on the pavement as she ascended the hill, her husband was unraveling the garden hose. She knew not to mention the rabbit. She turned to him before she ducked inside the house.

Why do you say Pittsburgh?

He blinked. What?

Why do you say you’re from Pittsburgh and not Youngstown?

His face darkened. It’s just easier. People know Pittsburgh. Nobody knows where Youngstown is.

He unfurled the coils and said nothing else and she tunneled into her office to prepare for her first meeting but opened the Times website to the popsicle recipe instead, the ingredients and directions too convoluted, wasting her last remaining article.

That night, after three back-to-back virtual meetings on webpage navigation, the last of which she barely heard as her husband pushed the lawnmower back and forth outside, she settled the baby into the rocking chair to nurse. He played with bubbles today, his teacher had said, and the babies all found a toad on the playground. Maybe she was too hard on this place. Maybe she was depressed. Maybe she needed the summer to make friends. As she switched breasts, the baby pointed out the window and whispered oh no. She looked past his tiny finger and saw nothing, just the slow-sinking sun, the freshly shorn grass. But after he nursed and she zipped on his footed pajamas, she carried him back to the window, and before she closed his curtains, she saw one lone rabbit standing at the edge of the woods. Her stomach seized. The third rabbit, what she’d forgotten all day through meetings. She pulled the baby to her chest and peered back out the window and there was no rabbit, just the wind pushing through the trees.

In retrospect, it was strange she’d met her husband in Berkeley, both of them Midwesterners. She’d gone to public schools, she was solidly middle-class, she’d ventured off to the University of Wisconsin, and she could have teetered either way after graduation, toward a place like San Francisco or back to the suburbs of Milwaukee. But she and her college roommate had decided to take a chance on California. They’d been living there two years when she met her husband, just starting his doctoral degree, at a bar on Shattuck where she’d gone to watch the Giants play the Brewers. He’d been enrolled in his program less than a month, still September, but he’d already absorbed the diction of academia. He said things like theoretical framework and insofar as, but she noticed his accent, the nasally fork and milk, how he ordered a Miller Lite instead of a local IPA.

Their baby was born as he finished his dissertation, a treatise on the postwar growth of American highways, and then he was flying out for job interviews and signing the contract to come here, Pennsylvania, a state she’d never visited until their plane touched down.

He told her midweek as they made coffee that he wanted to have a party. A summer kickoff.

Just a back-yard gathering, he said as he loaded the breakfast dishes into the sink. Nothing fancy.

She knew what nothing fancy meant. It still meant comparing microgreens farmers, sharing the name of the one person in town who sold $20 bags of ramps. It meant conversations naming television critics by name, if anyone had read Elsa Newman’s latest piece on Succession. She knew Alex Trebek, Pat Sajak. She’d never listened to NPR, never knew who Terry Gross was until this year.

Friday night, he suggested. We can build a bonfire. I’ll send out a few invites.

She felt exhausted thinking about a party, a gathering, whatever her husband wanted to call it. The baby had woken up last night, just for a few minutes, and she’d been the one who hadn’t fallen back asleep. But she remembered what her husband’s colleagues said about the magic of summer, the long lingering twilight, the first shimmering stars above a bonfire’s flames.

Okay, she said. She grabbed the baby from his booster seat at the kitchen table. She buckled him into the car, and he shouted driveway as they pulled out of the garage. She was still thinking about the party when the car plowed into another rabbit, of course it did, just before the stop sign.

She barely felt anything this time. She had no meetings until noon, nine a.m. on the West Coast. She pulled on athletic shorts and running shoes when she returned from dropping off the baby. She knew not to tell her husband, already out in the yard hammering together two-by-fours that would become raised beds, when she slipped from the house and began jogging down the hill.

There was again no rabbit when she’d driven back up the hill. Her hands no longer shook, she wasn’t even sure if she felt guilt anymore, maybe only curiosity or else faint annoyance that rabbits kept running into the road. She edged her way down the street, jogging along the gravel shoulder, until she found the approximate spot where all four rabbits had darted from the bushes. She’d worry about ticks later. She took a deep breath and pushed into the tall wildflowers.

Her hands shoved aside desiccated cattails and rope-thick weeds. She felt low thorns scrape against her bare shins, tiny gnats buzz her ears. The high morning sun bore down, low and heavy, a curtain of humidity cloaking the hill. She burrowed through the grass until she was certain she’d covered every inch of where any rabbits might be hiding, but she found no rabbit hole, just snarls of thistle and dandelion.

It was inexplicable, she thought that afternoon during a meeting on search engine optimization, scratching her dully itching legs beneath the desk. So many rabbits, but only when she was alone, as if she were going mad. Her husband wouldn’t believe her if she told him. She wanted to feel sad, four lives she’d taken in under a week. But as her computer monitor shifted into a full-screen share, one of her colleagues’ voices rising into presentation mode, she realized how numb she felt, how quickly the monotony of the morning drive had settled in.

That evening, after they’d bathed the baby and put him to bed, they stood in the back yard beside five new raised beds.

I still need to put up a deer fence, he said. It might take another day or two.

These are gorgeous, she said and felt through her whole body what it meant to mean it. Five boxes of nailed natural wood, soft mounds of fresh-tilled mulch. She realized, in her malaise throughout the entirety of winter, how little she’d verbalized anything positive to him at all.

We can start with tomatoes this summer, he said. Maybe some herbs and kale.

She knew from her own Midwestern back yard that these were easy crops to begin with, a test garden to make sure the plots would take. She reached out and touched his back, the same tenderness with which she’d rubbed the baby’s back less than an hour before.

You did a good job, she said.

His shoulder slid away from beneath her hand. We have three folks in for Friday night.

The new music professor and his wife, he told her, plus a second-year film professor. She didn’t like the film professor. At a faculty party, a Tom Petty song had been blasting from the stereo and he’d leaned in and asked if she knew what film it was in and she said Silence of the Lambs and he patted her head and whispered good girl and she’d wanted to rip off his hand. But the garden beds were raised. The crickets were whining. The sun was sliding behind the trees. As they stepped back into the house, she felt something like contentment, though she saw how long her husband stood at the kitchen sink scrubbing the dirt from his hands, the same dirt that once caked his father’s fingernails every day after work.

She hit another rabbit the next morning. She knew she would. And then another the following morning, the sixth one, an expectation so expected and so increasingly vexing that she almost felt her foot press down on the pedal when she saw the fur missile out from the grass. She said nothing to the baby’s teacher. She said nothing to her husband, already out in the yard pounding stakes, stringing up netting. She was tired. The baby had awoken again in the night, crying until she soothed him. The meetings had proliferated. What had already been a packed week of user experience navigation had ballooned into troubleshooting snags discovered in the grocery site’s digital pathways, plus the baby was cranky, the baby had catapulted his peas to the floor, the baby had woken up wailing two nights in a row.

And she noticed her husband’s preparations for this gathering, what seemed like a party the closer Friday night came. How he went out for mulch and came home with a bottle of Jameson from the town liquor store, then a bottle of Campari, then a bottle of cognac.

It’s only three people, she said on Thursday night when he came home with two types of cheese from the grocery store, just brie and an aged cheddar, the fanciest the town store could stock.

It’s our first party, he said. Why not make it special?

Now it’s a party?

His eyes flashed at her. What’s your problem? Do you not want to have anyone over?

She didn’t know what her problem was. She never wanted to have anyone over. She longed for Wisconsin, where a fire was a fire, marshmallows, and graham crackers. She thought of telling him about the rabbits, of saying out loud that she’d killed six, that this was what was wrong with her, that she barely even cared.

Yes, she sighed. I want to have your friends over.

Our friends, he corrected her. Yours and mine. We’re here, together.

She leaned against the counter and looked at him, the day’s mulch small black moons on his fingertips. It wasn’t just the rabbits. She didn’t know what to say to him and wondered if this was the shift, not the winter or the gray skies or the fact of this place, but that she couldn’t find the words anymore that would communicate to him that these were not their friends, only his, that every single person she’d met since they moved here had gazed right through her as if she were a ghost and that he was starting to do the same.

Okay, was all she said. They’re our friends.

There was nothing left to do. The baby would be crying in only hours, she knew.

Her husband was already out in the yard when she woke up, the sound of hammering drifting in through the open screens. The baby waited patiently in his crib, having not awoken at all in the night, the first glint of promise. Today could be different. The garden beds were nearly done, the stakes raised, her husband malleting the netting into each post. The seedlings waited in their pots beside the beds, visible through the kitchen window as she fed the baby breakfast. Tiny kale. Tomato vines. The sprouts of basil leaves. Through her day of intensive meetings, her husband would place them in the soil.

She thought about that last rabbit as she buckled the baby into his car seat, how it flattened like rolled dough beneath the car tires. The baby shouted tight! She reversed out of the driveway. The baby whispered garage. She reeled down the road and the sun crested over the hills and she knew she was well within the speed limit, she was creeping toward the stop sign, she was feeling the first murmurings of that lightness in so long, this last day of meetings and the summer spooled out ahead, her heart was a floating buoy when she felt the familiar weight beneath the tires, that same thud that was somehow still sickening.

She glanced in the rearview mirror. She watched the small outline of a rabbit’s head raise from a crushed mass, then lie still. This was number seven. This was the end of an unfathomable year. This was routine. Even still, her heart sank, an anchor falling to the ocean floor.

She dropped the baby off. She watched him patter into the classroom toward another child, more toddler than baby. She watched him grab a basket of plastic toys. Heat pricked the edges of her eyes. As she drove to the grocery store, for the water crackers and mixed nuts she promised she’d pick up on her way home, she thought about the rabbit. She thought about all the rabbits. She wondered what kind of parent this place would make her, if her son’s upbringing would look anything like her own, with its bug boxes and s’mores, if he’d soon graduate from bread and apple to lobster roll and charcuterie. She thought of her own mother. It was easy to romanticize her Wisconsin childhood. But as she pulled into the grocery store parking lot, she recalled the time in junior high when she heard her mother crying. It was late at night, and her mother must have thought everyone was asleep. They’d gone to the mall earlier and she’d asked for a pair of Jordache jeans and her mother had bought them and only later she’d overheard her mother lamenting to her father downstairs, $40, I can’t believe my child needs $40 jeans.

That night, as she nursed the baby, she wondered if this was the way of all parents. This class ascension. This autopilot life. This capacity to ramrod over a rabbit and not blink. This horror of water crackers and fine liquor, if this kind of moving up meant happiness at all. She lifted the baby and held him to her chest and felt the ripple of his beating heart. He pulled away from her and pointed at the window. She heard him whisper bunny.

She turned and looked, a needle of ice piercing her chest, and in the dimming twilight at the edge of the darkening woods stood a single rabbit, nose twitching, staring straight into the window.

The film professor arrived first, followed soon by the music professor and his wife, the last layers of sun lining the clouds in pink. She hated that she thought of the music professor’s wife as just his wife. Her husband mixed each of them a Boulevardier while she threw two new logs on the fire, the flames flickering off into the dark as her husband’s colleagues had promised.

Even though it was still May, she listened as they talked about the fall semester through the first round of drinks. She hated that she knew the phrases. Core curriculum. New student orientation. Everyone here would look at her blankly if she said editorial calendar or content plan. She’d spent the entire day in five hours of virtual meetings, a day that felt like it hadn’t even happened.

But she’d promised to try. She gestured toward the raised beds at the edge of the back yard.

We just finished those today. She nodded at her husband. Or, I should say, he did.

I was just noticing those, the music professor said. What are you planning to grow?

Mostly kale and tomatoes, her husband said. And some herbs. We’re starting small.

She watched the first stars poke through the dark and imagined the baby toddling through the garden, showering the beds with his tiny plastic watering can. He’d fallen asleep fast. His window faced the back yard, but he would sleep soundly, her husband assured her, a gathering of only five people. She wanted a summer of gardening hoses and sprinklers and new seedlings for the baby. She wanted a summer that felt like the kinds of summers she’d once known.

Refills, anyone? her husband said.

The music professor motioned to his glass. I’ll have another, if it’s not too much trouble.

Her husband grabbed each of their glasses and caught her eye as he headed inside. I’ll just have a beer, she said. She’d picked up a six-pack at the store along with the crackers and nuts.

So you two are staying put this summer? the film professor asked. No travels?

She shook her head. Maybe just a weekend trip here or there. Since this is our first summer here, we’re planning to just settle in and explore nearby. How about you? Any Memorial Day plans coming up?

He shrugged. Same as you for the summer, maybe a trip here and there. I wasn’t planning on going anywhere for the holiday weekend, but I lucked into a place in Cape Cod for a few days.

Sounds nice, she said as her husband returned with drinks, but what she really felt was tired. Just once, she wanted someone to say they’d lucked into a rental in Branson or the Jersey Shore, not Cape Cod or the Hamptons. Summer vacation to her once meant the Wisconsin Dells. To her husband it once meant Put-in-Bay off Lake Erie. A place he’d never mention now, filled with bumper boats and miniature golf.

We’re thinking of remodeling our bathroom, her husband said, now that the garden is complete.

This was news to her. She looked up at him across the fire, but he didn’t meet her eyes.

You need a recommendation? the music professor asked. We have a guy who’s good with plumbing.

Her husband nodded, though she knew he could remodel both of their bathrooms on his own. She knew her husband had spent his entire teenhood shadowing his father on bathroom retiling and plumbing fixes, trades his family assumed he’d take on after high school instead of pursuing community college.

Who built your garden fence? the film professor asked. I was thinking of finally starting a garden too. She expected her husband to make the correction, to take the credit, to say, It’s easy enough to build one yourself, but she felt her throat close when he spoke.

A guy in town, he said softly. I got a referral through the local nursery.

But you built them, she said, louder than she meant.

The fire popped. She watched her husband, and he didn’t look at her across the blaze.

Just the beds, he corrected her, his voice low.

She blinked through the fire, her beer sweating in her hands. She’d heard him pound the stakes, she’d seen him scroll the netting out the kitchen window.

Refills? he asked and the music professor nodded.

Another Boulevardier.

It wasn’t true, she’d recalled that morning as she stood in the beer aisle surrounded by refrigerated cases filled with six-packs, that her husband had never hit an animal. She remembered one night she’d nearly forgotten, just two weeks before their baby was born.

They’d been out for a fancy dinner, their last date before the baby arrived, and the bay’s fog had rolled in after dark and on the drive back, as they rounded a curve, her husband plowed into a lumbering raccoon that’d been crossing the road. She’d felt the thump, she’d screamed and veiled her hands across her face. What she remembered in the beer aisle was how her husband just kept driving, how he didn’t even stop to check the rearview mirror. There’s nothing we could have done, he said when they reached their apartment and she was still crying, his tone implying that her reaction was third-trimester hormones. He’d finished his dissertation three weeks later, already in first-round interviews for this job, this place that was now their home, this back yard where they stood drinking two beers after the film professor and the music professor and his wife left, the fire’s sparks still crackling into a sky salted with stars.

She didn’t know what to say to him in the silence. She hadn’t known what to say to him, she knew, for nearly the entire year they’d lived here, maybe long before.

That was fun, she said.

He turned to her, his eyes narrow in the flame light. You don’t have to lie.

She would have screamed if the baby’s window wasn’t so close.

Oh, I’m the one lying?

He swallowed a gulp of beer. Exactly what is it that you want from me?

She felt her hand clench around her beer bottle. She wasn’t numb, she wasn’t lonely, she wasn’t dulled by the routine of these days. She was the angriest she’d ever felt in her life.

I want you to look at me, she said. No one here does, not even you.

What does that even mean?

She watched the fire spark, her eyes burning back their afterimage. She wanted to hear the words outside of her mouth.

I hit six more rabbits, she said. I’ve hit seven rabbits in the past week. Did you even know?

He laughed. How would I know you if you didn’t even tell me?

Would you have cared?

Lower your voice.

Why? she shouted. In case the neighbors hear? What would they even think?

You’ve barely given this place a chance.

You’re right, she said. I hate it here. I fucking hate it here.

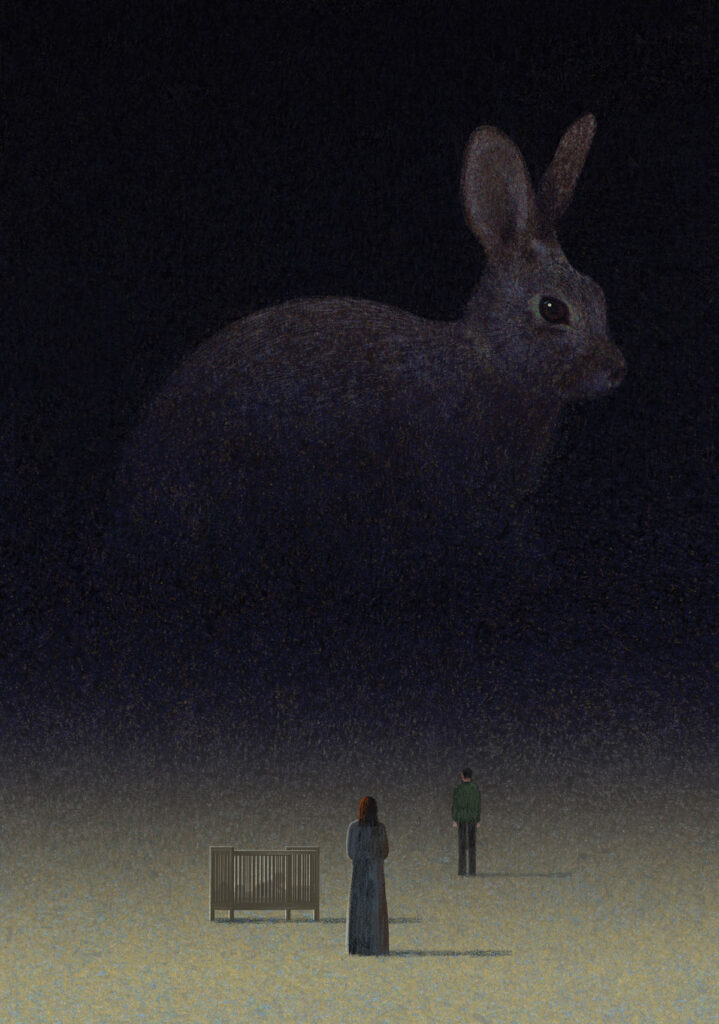

She didn’t know by here if she meant this place or this marriage or this entire life they’d built together, this life that felt so far from what she wanted for herself and for the baby. She glanced at the night sky, clouds pushing in, a low half-moon still visible above the house. She didn’t even need him to look at her. She just needed them to be who they were without hiding, to anyone else or to each other. She glanced at her husband and wanted to say it, what the fuck are we doing here, but he wasn’t looking at her anymore, he was staring out into the yard where all at once she heard it too. He turned on the porch light, an illumined halo that spread into the grass and to the edges of the fenced garden where a clear hole had been chewed straight through the netting, one lone rabbit standing in the center of the raised beds.

Motherfucker, her husband whispered.

Leave it alone, she said, a strange fear bubbling up her chest.

Get out! her husband shouted at the rabbit.

The rabbit chewed one leaf of kale and blinked.

You’ll wake the baby, she hissed.

Oh, now you care about noise? he said too loudly and turned back to the rabbit. She heard a soft whimpering from the baby’s window. Get out! her husband shouted again. Get out! Get out! Get out!

You’re going to wake him up! she hissed, and her husband laughed, of course he laughed, he would laugh if she rolled down the hill on Monday morning and mowed right over another rabbit and the morning after that and the morning after that, as if she was a terrible driver, as if all of this was her fault, as if she’d made every fucking thing up. Her husband shouted again and the baby’s whimper rose from the window into a cry and in the porch’s light she saw the rabbit’s twitching nose, the rabbit’s soft munching, the rabbit’s hollow eyes blankly watching both of them, and she felt her hand seize her beer bottle and hurl it so hard that it bent through the mesh and struck the rabbit’s skull.

She felt nothing, no thump, no certainty of fur flattened beneath her tires. Her husband went silent. The fire sparked and popped into the dark. The rabbit slumped on its side. Her hands shook.

Through the window screen, the baby wailed and wailed.