Raising Mank

The Academy Award–winning film about the making of Citizen Kane is really a window into the tumultuous, brutal side of Hollywood’s golden age

I first fell in love with director David Fincher after watching Se7en (1995), a film about a fictive serial killer with a menacing softness that lent a poetic flair to the truly monstrous—and that made all of us in the theater sit in the shadow of madness. Fincher’s best film, Zodiac (2007), about the real-life serial killer who preyed on the San Francisco Bay Area during the late 1960s, was also a subtle polemic on the idea of monstrosity. Fincher’s latest film, Mank—which was nominated for 10 Academy Awards this year and won for cinematography and best production design—is no exception. The historical figures it portrays, including Orson Welles, Louis B. Mayer, and William Randolph Hearst, all have a monstrous side. It’s Hollywood, after all.

Mank could never have been conceived without the subversive sleight-of-hand of Pauline Kael, whose 1971 two-part essay in The New Yorker, “Raising Kane,” might easily have been called “Waking the Dead.” By 1971, Herman J. Mankiewicz, or Mank, was all but forgotten as the Academy Award–winning cowriter of Citizen Kane (1941), and Kael was a lonely warrior on his behalf. She condemned Welles as a charlatan and the greatest loser in Hollywood history. It was Mank, she wrote, who was the sole author of Citizen Kane.

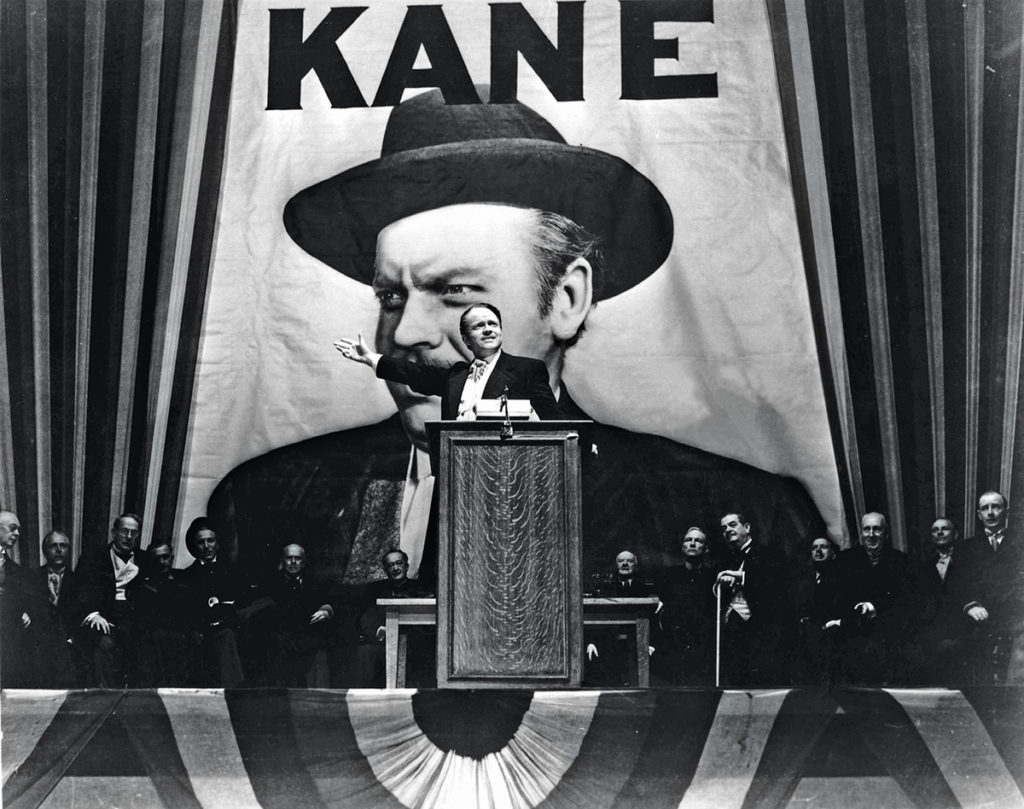

This is what Fincher feasts upon in Mank. Like Kael, he argues for the greatness of Citizen Kane while diminishing Welles’s participation in its making. Tom Burke plays Welles as a cocky young Mephistopheles in a barbed beard, with a black cape and a floppy black hat. He’s here to hinder Mank—played by Gary Oldman with languid panache—not to help him.

Fincher’s father, Jack, wrote the script. A former journalist and magazine writer—he had worked as the San Francisco bureau chief of Life magazine—Jack shared his love of films (including Citizen Kane) with his son. After Jack had turned to writing screenplays, David urged him to read Pauline Kael and suggested that he write a script about Herman Mankiewicz. Jack did, and it took David nearly 30 years to get the film made. It serves as an homage to his dad, who died in 2003.

The story of Welles’s relationship with Mank is not a pretty one. A refugee from the Algonquin Round Table, a mecca in Manhattan for an elite band of writers who believed in the sanctity of their own acerbic wit, Mank went out to California in 1926, before he was 30. He became the head of Paramount’s scenario department in 1927 and was soon the highest-paid screenwriter in Hollywood. “Millions are to be grabbed out here and your only competition is idiots,” he wrote to journalist Ben Hecht.

Mank helped produce and write (without screen credit) two Marx Brothers classics, Monkey Business (1931) and Horse Feathers (1932), but by 1939, when Welles first hired him, he was a drunken misfit and a barely employable beggar. He wrote scripts for Welles’s radio show, The Campbell Playhouse, receiving no credit for the work he did. He had the same kind of contract for Kane: Welles, always the egomaniac, even at 24, offered him $1,000 a week but no screen credit. (According to Robert L. Carringer in his book The Making of Citizen Kane, Mank earned $22,833.35, a hefty sum in 1940.)

Lily Collins as Rita Alexander, the English typist hired by Orson Welles to assist Mank, played by Gary Oldman (Netflix/AA Film Archive/Alamy)

Welles’s arrival in Hollywood was a study in contrasts. By the time he landed at RKO Pictures, the floundering studio that ended up making Citizen Kane, Welles had already been on the cover of Time and had become fabulously famous as the producer-director-star of The Mercury Theatre, which put on, among other things, a series of literary radio dramas that aired on CBS every week. He was also a prankster and a provocateur, much like Mankiewicz. But Welles, the Boy Wonder, got away with his pranks. On Halloween eve, October 30, 1938, he presented War of the Worlds, which announced a mock invasion from Mars. It was this broadcast, and Welles’s whirlwind activity in the theater—staging a voodoo Macbeth with an all-Black cast and a modern-dress Julius Caesar—that brought him to RKO as a four-way wizard: producer, director, actor, and writer, with authority over the final cut on the films he produced. Naturally he wasn’t willing to share any credit with a has-been like Mank, who was hired not by RKO but rather by Welles’s own Mercury Theatre.

But Welles had a real problem. He didn’t know how to sculpt a screenplay. Mank broke his leg in an automobile accident, and in the spring of 1940, Welles shunted him off to Victorville, a desert town 60 miles from Los Angeles, to write the first draft of Kane. This episode serves as the touchstone of Mank. Welles had the cofounder of The Mercury Theatre, John Houseman (played by Sam Troughton), accompany Mankiewicz as his babysitter and bulldog.

“Write hard,” Houseman tells him. “Aim low.” But Mank decides to write a masterpiece in the Mojave Desert. “The narrative is one big circle,” he says, “like a cinnamon roll.” And that prismatic form of a flashback within flashbacks does contribute to the ingenuity of Welles’s film. Mank, feeling the force of his own writing, declares to Welles that despite his contract with the Mercury, he wants credit for his screenplay. And there’s the rub. “It was not my interest to make a movie about a posthumous credit arbitration,” Fincher told The New York Times last December. “I was interested in making a movie about a man who agreed not to take any credit. And who then changed his mind. That was interesting to me.”

Mank sees himself as some kind of Ahab, chasing a great white whale composed of Welles, Hearst, and Mayer. But he’s far too passive in his pursuits. The real revelation of Mank is not Mank himself but the character of Hearst’s mistress Marion Davies, portrayed by Amanda Seyfried with a charm and a vulnerability that provide the film with much of its flavor. “Don’t kick Pops [Hearst] when he’s down,” she says after she has read Mank’s script.

What we don’t see in Fincher’s film is any depiction of the actual collaboration between Welles and Mankiewicz. It isn’t clear who came up with the idea to model the character of Charles Foster Kane on Hearst—to therefore use Hearst as the film’s whipping boy and central incarnation. Welles, with all his boisterousness, bears as much resemblance to Kane as Hearst does. Mank must have sensed that and used it in the script. There were seven drafts, and Mank was away on assignment to MGM during at least four of them. How much of the script was altered in the midst of shooting Kane? “Films are not made in the minds of screenwriters,” declared director Werner Herzog, and he’s right.

The title, Citizen Kane, came not from Mank or Welles but from RKO President George J. Schaefer. And even though Mayer and the other moguls tried to destroy Kane, as Mank suggests, it’s still the ultimate studio film. The moguls were frightened of Welles’s wizardry, of his desire to craft a film with a wayward beginning, middle, and end. When Welles came to Hollywood, he didn’t know the first thing about film production. RKO was like a great big toy electric train to him. He couldn’t have constructed Kane without cinematographer Gregg Toland, who arrived on the set with his small army of cameramen, or art director Perry Ferguson, who helped create many of the film’s special effects.

Welles was a dynamiter; he wanted to tear apart Hollywood’s fixation with telling a strict, linear tale. And he was so relentless in driving his film crew to create effects that had never been tried before that he became known on the set as “Monstro,” after the whale in Walt Disney’s Pinocchio. His makeup artist, Maurice Seiderman, managed to age the 25-year-old Welles into a 70-year-old Kane with a false nose and a rubber mask. There’s nothing quite as poignant as the moment when Kane tears up the quarters of his second wife, Susan Alexander (Dorothy Comingore). Welles moves with a staggering gait that no one could have equaled. It’s the dance of a broken man, captured with miraculous depth by Toland’s camera. With his booming radio voice, Welles invented Kane out of the markings of Mank’s script and his own bearish energy.

Recently, I reread Kael’s “Raising Kane” after a lapse of almost 50 years. The essay holds up, but I was startled to see that it isn’t really about Welles or Mank and the birth of Kane. It’s about the golden age of Hollywood, as she remembered it, and her own girlhood at the movies. She understands that the movie industry of the ’30s and ’40s was a producer’s paradise, yet it was the horde of writers who came out to Hollywood, who worked in tiny cribs at the studios, often in pairs, who provided the real flavor of the era, with their rat-a-tat-tat dialogue in such films as Bringing Up Baby (1938) and His Girl Friday (1940). “Hollywood destroyed them,” Kael writes, “but they did wonders for the movies.”

There’s Charles MacArthur, George S. Kaufman, Ben Hecht, Dorothy Parker, and S. J. Perelman, most of whom appear in Mank. “They escaped the cold, and they didn’t suffer from the Depression,” according to Kael. “They were a colony of expatriates without leaving the country,” and while they stayed in Hollywood, “American letters passed them by.”

William Faulkner was also out in Hollywood and worked on several scripts for Howard Hawks, including The Big Sleep (1946). But he wrote his best novels long before he settled for a little stay in the California sun. And F. Scott Fitzgerald labored on an unfinished draft of The Last Tycoon (1941) while he himself was a Hollywood hack. His hero, Monroe Stahr, is a fictional portrait of Irving Thalberg, the prince of Hollywood producers, another Boy Wonder, like Welles. Thalberg was the one who contrived the devilish idea of having dueling teams of writers work on the same script.

Herman J. Mankiewicz, less than five years after Citizen Kane appeared (Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy)

A “blue baby,” born in Brooklyn in 1899 with a damaged heart, Thalberg lived to the age of 37 and was head of production at MGM by the time he was 24. He was also monstrous in his own way. He brought the Marx Brothers, with all their joyous anarchy, from Paramount to MGM, telling them that their previous films suffered from a surfeit of laughter—“one laugh too many.” They never made another madcap film. Thalberg tamed the Marx Brothers, made them very rich, and buried whatever genius they had.

Played by British actor Ferdinand Kingsley, he appears in Mank as the man who produced doctored newsreels and phony radio spots that helped Frank Merriam defeat Upton Sinclair in the 1934 California gubernatorial race. A socially minded author-activist, Sinclair had captured the reins of the state’s Democratic Party; he intended to tax the rich, particularly the moguls, some of whom threatened to move their studios to Florida if Sinclair became governor. (Merriam won the election handily.)

Thalberg was an anachronism during his lifetime. He wanted to produce “classics,” linear masterworks that would last forever, but he didn’t understand the innate anarchy of the screen. Neophyte as he was, Welles understood that the screen could breathe, that it was as porous as human skin, and that it reflected all the confused feelings—the pain, the dread, the laughter—of its own time. Thalberg could fashion movie stars like Greta Garbo and Clark Gable, who turned Hollywood into a global film capital, but these stars, however famous, were no more than rich indentured servants with seven-year contracts that the moguls could break at will.

With its tyrannical bosses, its talented technicians, and its bestiary of beautiful faces, Hollywood remained a provincial fairyland, a racially divided village, where Black Americans like Bojangles might dance in a Shirley Temple saga but couldn’t be seated at one of its fancy nightclubs, such as the Cocoanut Grove. Hattie McDaniel was the first Black actor to win an Academy Award—for her performance as a house slave in Gone With the Wind (1939). But she had to sit at a segregated table in a far corner of the Cocoanut Grove, where the Academy Awards were being held.

Thalberg was also one of the creators of the Motion Picture Production Code, which gave Hollywood the valuable gift of self-censorship so that it could avoid being censored by outside forces, such as the Catholic Legion of Decency. The code could stifle any “licentiousness or suggestion of nudity—in fact or in silhouette.” It also forbade any image of miscegenation on the screen, or the slightest hint of a gay or lesbian relationship. Yet Hollywood was a town where producers and other potentates exploited women (and men) on and off the screen. Women were presented as objects of desire to be gazed at and were subject to producers’ whims. Harry Cohn, president of Columbia Pictures, reportedly interviewed potential starlets in his office without bothering to wear a shirt. This marked Hollywood almost as much as the films he delivered.

The saddest tale of Hollywood’s golden age concerns a forgotten novelist, Daniel Fuchs, who wrote a trilogy about Brooklyn that sold roughly 2,000 copies. He barely survived as a substitute teacher at a public school in Brighton Beach and went out to Hollywood in 1937, the year I was born. Like most other screenwriters, Fuchs worked in a studio crib, often in tandem with other writers. In 1971, he wrote a little memoir, “Days in the Gardens of Hollywood,” for The New York Times Book Review. “The studios exude an excitement,” he declares, “a sense of life, a reach and hope, to an extent hard to describe.”

Fuchs was like a perpetual tourist in an undiscovered country. “Everything in this new land [was] wonderfully solitary, burning and kind,” he writes. He loved to roam the backlots, visit “the Western streets, the piers, the empty railroad depots, the somnolent New Bedford fishing village of 150 years ago.”

But Fuchs wasn’t as blissful when he had to dive into the Hollywood dreamscape and work with some producer on a script. And once, on the 14th week of an assignment, utterly blocked and unable to write a word, he wondered if he could think of “some way of committing suicide without dying.” Like a cavalier, he offered to go off salary. His bosses considered him a crazy man. Fuchs found the answer “in a dazzling rush of clarity that scares me: all I have to do to commit suicide without dying is to murder the producer.”

This was the Hollywood of Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Welles, a crazy house that both of them tried to conquer. And in his innocence and megalomania, Welles was able to construct Citizen Kane, with the help of Mank and a host of technicians who understood that it was the best work they would ever do. Finally, this is what is missing from Mank. Buffoonery abounds; Gary Oldman entertains us with his reckless behavior, but we never really see Mank as an integral part of what many people consider the finest movie ever made.