Houston native Raul Gonzalez’s art focuses on themes of immigration, construction, and confronting stereotypes. He is preparing for three solo exhibitions later this year, while also taking care of his two young daughters as a stay-at-home father.

“I wasn’t exposed to any fine art until I was in high school. Before then, the only exposure I had to art was in the form of movie posters, video games, T-shirts, Disney movies, and stuff like that. I got exposed to fine art by seeing artist characters in movies. There’s this one movie, Bound by Honor, about Chicano family members in Los Angeles. One character is a really talented artist and gets represented by a gallery. The first time I saw that film, I was 15 years old, and I was like, ‘I didn’t know artists do stuff like that!’ It made me ask, how do I become an artist? I had no idea what a fine artist was. Later, I found my way into the art program at University of Houston. I was drawing my whole life, and once I started painting, it came easily. Even mixing colors—once I started, I didn’t stop. I got involved in the Houston art scene, joined an art collective. So I was doing a lot to learn self-sustaining practice. For 10 years of my life, I was working at least one full-time job and sometimes one or two part-time jobs on the side. Then I decided to move to San Antonio, go to grad school, and get my masters. Once I moved here, I was like, ‘Okay, I’m going to be a full-time artist and figure out whatever I need to do to work as a full-time artist and not have to get any other job.’

My dad has been working construction now for over 35 years, and while he’s worked construction, he’s always had two or three other part-time jobs. I’m sure a lot of people share the same type of story—they come over here as immigrants and they work their butts off doing jobs no one wants to do. My dad worked extra jobs so he could have money for us kids growing up, and also so he could send money back to his family in Mexico. That’s what everybody does. On Friday, people are cashing their checks and sending money back to their families. A lot of opportunities come from construction. If you look at the turn of the century in America, there are all these black-and-white photos of skyscrapers and these immigrants—they’re all from Europe. We glorify those images and we’re like, ‘Wow, look at that.’ There are people doing that now, but they aren’t building skyscrapers, they’re building highways and bridges.

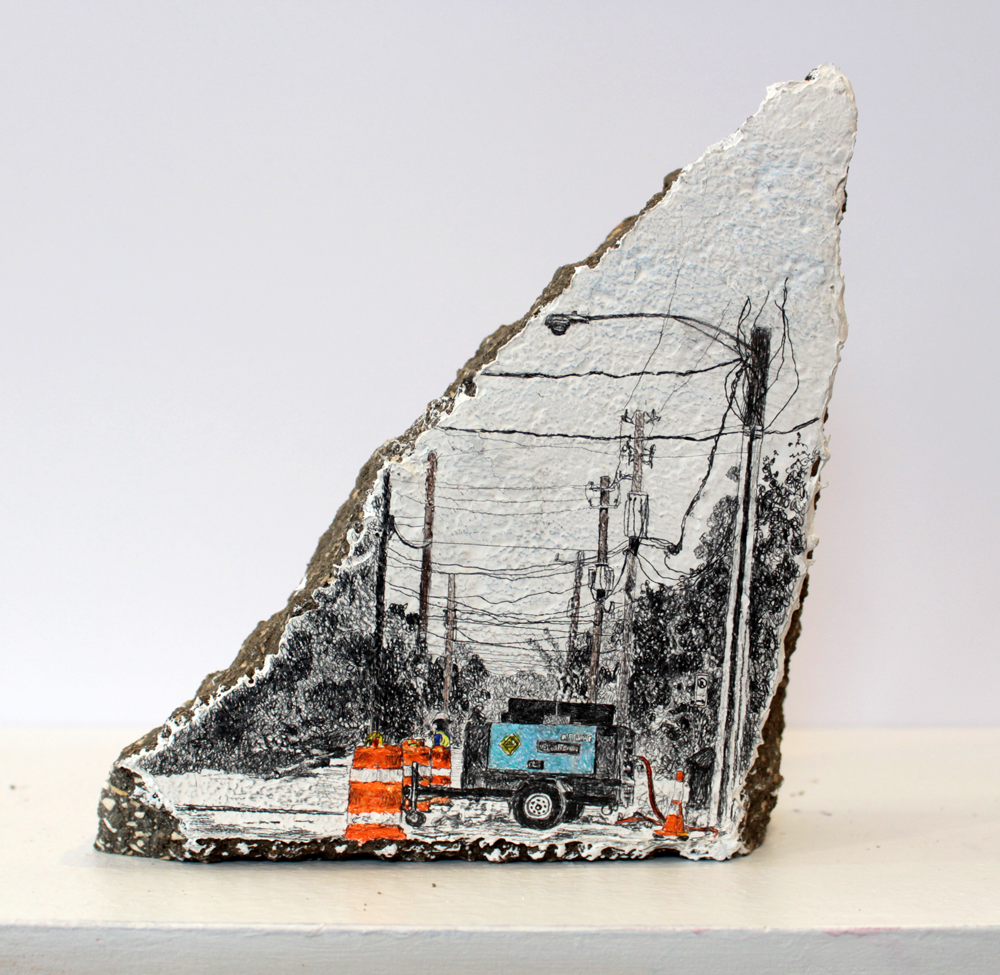

This series was all about highlighting construction scenes and people you see when you’re driving around. They’re on the side of the road doing all this labor, and it’s hard work. Most of the time, they either get neglected or people don’t even think about them—it’s just like they’re part of the landscape, they’re part of the construction scene, they’re not even people, especially now with all the rhetoric and the news, and people talking down workers who are immigrants.

I spent a lot of time driving around Houston—there’s always traffic, there’s always construction. People complain about it, but once all that work is done, we have highways and roads that weren’t there before. We take them for granted. I want to recognize people who are constantly building and fixing everything around us. And realizing, they’re a part of all this. I put these images on concrete so it’ll be a little bit more striking than a traditional image.

When you think of concrete, you think of laying down the foundation for a home or laying down a foundation for a civilization. And so, the material itself all of a sudden carried symbolism. It was the perfect replacement for a piece of paper or a canvas. A lot of my work is about demystifying the canvas—it doesn’t have to be sacred. I want this series to have a little bit more life than just a nice striped canvas that looks like it was made to never be touched.”