At age 11, I entered Hasmonean High School in London having daydreamed my way through primary school, enduring repeated reprimands for inattention. Mrs. Merkel, my indefatigable new English teacher, noticed me and took my writing seriously. She read my essays aloud, praised my ideas and creativity and listened to me in a way that no primary school teacher had. The study of English, she said, was the gateway to the world and everything in it: geography, history, science, art, music, culture, politics, nature.

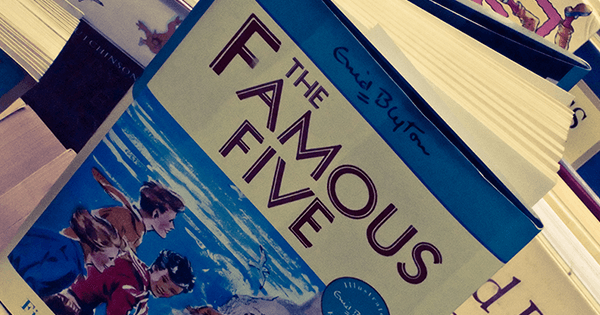

But Mrs. Merkel also issued a warning: Do not read anything by Enid Blyton. Blyton (1897–1968) was a popular and prolific writer of children’s adventure stories. She wrote about 800 books, selling more than 600 million copies worldwide, and according to UNESCO, is the fourth most translated author in the world, just behind Shakespeare. The trouble is, her plots are often elitist and full of stereotypes. The BBC banned Blyton from its airwaves for nearly 30 years, from the 1930s to the 1950s, because executives thought her books lacked literary value.

Fortunately, for me Mrs. Merkel’s injunction came too late. By the time I reached high school, I had read Blyton’s oeuvre almost in its entirety. Thanks to the adventures of the Famous Five and the Secret Seven and the jolly boarding school girls of Mallory Towers and St. Clare’s, I had learned about such curiosities as potted meat for picnics, children who had “people” not parents, a magic faraway tree with rotating lands at its crown (“Topsy-Turvy Land,” “The Land of Take-What-You-Want,”) midnight feasts, a courageous girl called Georgina who dressed as a boy and insisted on being called George—yes, back in the 1940s—and the doings of some very independent children who solved mysteries without the aid of pesky interfering adults.

That confidence and independence—including the ability to choose my own reading material—is a lesson I learned from Mrs. Merkel, as well, even if it wasn’t quite the message she intended to impart. As Walt Whitman wrote in his Preface to Leaves of Grass, “re-examine all you have been told at school or church or in any book”—a lesson I hope to convey to my own children, as well. These days, I’d take Blyton’s secret islands and curious, questioning find-outers over that twinkly princess pap and insipid Dora-The-Explorer-Thomas-the-Tank-Engine bland bilge that now passes for popular children’s literature. In fact, I’m planning on buying some of Blyton’s series for my children. I do hope that Mrs. Merkel doesn’t mind.