On July 4, a great artist and a remarkable human being, Abbas Kiarostami, died—unnecessarily, as it turns out. I knew him slightly, having interviewed him several times and written about him often. He was, to my mind, not simply the greatest Iranian filmmaker but one of the two or three greatest filmmakers alive (and now I have to amend that last word). Although his name barely registered on the American public, he was a revered figure on the international art film festival circuit. He began making short films about children, having been invited to start the filmmaking branch of the Kanoon Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults in Iran. From these shorts he graduated to superb feature films, such as Homework, Close-Up, Where Is My Friend’s House, And Life Goes On, Through the Olive Trees, and The Wind Will Carry Us, which combined neorealist humanism in the tradition of Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, and Satyajit Ray, with a formalist rigor (choreographed long-duration shots) and a playful, postmodernist self-referentiality. In a sense, he solved the dichotomy between fiction and documentary. His films were gifted with patient observation and curiosity about ordinary people; there were always humorous bits, they breathed naturally, and they were healthy for you—that is, they made me feel engrossed, suspenseful yet at peace, when watching them.

Here is an excerpt from an interview I did with him in 1996 that conveys that thoughtful part of his sensibility:

PL: I have a question about your sense of pace. Your movies have these alternations of tension and relaxation, of stillness and conflict. Some scenes seem to go on a long time, and then at other times the drama is very condensed.

AK: That rhythm is based on nature, life: you know, day, night, summer, winter. The contrast between these things is what sustains our interest, because even if you love spring, you can’t have spring all year long or you’d get bored. I think there is a pace to nature, and if you adopt the same pace to your films, in the sense that you manipulate it—at some point caress it, at some point be rough with it—that will cause interest.

PL: I wonder if it’s also a cultural difference, because American movies are becoming more and more constant action. You’d rarely get a sequence in an American film like the one in Through the Olive Trees where the two old men are philosophizing, since it doesn’t “advance the plot,” so to speak.

AK: I’m really enjoying this conversation, because these are the kinds of things that I was always thinking about, but no one ever brought them up. So I worry that maybe they don’t understand. In the most recent example, Through the Olive Trees, we were making a movie about making a movie, but there were moments in the film when we weren’t “doing” anything. I was even sometimes tempted to put black leader in between the scenes—because I was constantly hunting for scenes in which there was “nothing happening.” That nothingness I wanted to include in my film. Like in Close-Up, where somebody kicks a can. But I needed that. I needed that “nothing” there.

PL: Do you need it for aesthetic or spiritual reasons? Or both?

AK: At some point those two intersect. If you bring out the aesthetic aspect, then maybe you’ll see a reflection of the spiritual as well. The points where nothing happens in a movie, those are the points where something is about to bloom. They are preparations for blooming, similar to a plant which has not emerged from the earth yet, but you know there are roots there and something is happening. … So when people tell me “Your movie slows down here a little bit,” I love that! Because if it didn’t slow down, then I couldn’t lift it again.

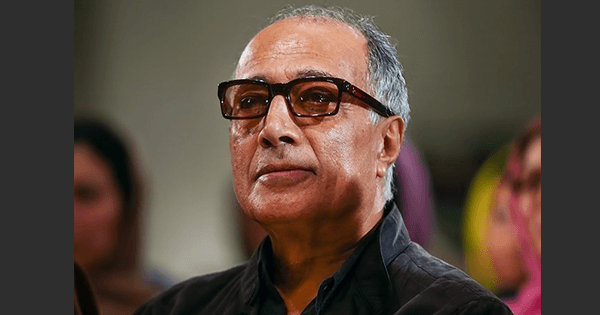

Through his films and his bearing, Kiarostami embodied the antithesis of the scary Iranian fundamentalist image we were being bombarded with in Western media. He felt no obligation to make art that polemically criticized the mullahs—that was not his style—but you were never in doubt of his cosmopolitan, secular sympathies. He was a very handsome man, and a natty dresser who always wore sunglasses, who carried himself with the aristocratic elegance of an Italian prince. Before our interview, I met Kiarostami and his translator in a hotel lobby near Lincoln Center, and we went upstairs to his room, where the translator immediately drew the blinds, explaining that “sunlight is the enemy of Mr. Kiarostami.” So the shades were not an affectation of cool. Before we could begin, my mother-in-law rang my cell phone, warning me to be on the alert: she was nervous about my getting stuck with this Iranian Muslim in a hotel room. I joked about it with Kiarostami. Many years later, as I was interviewing him again, this time about his marvelous Japanese picture Like Someone in Love at the New York Film Festival, he suddenly cried in the middle of the event: “I remember now, the last time your mother-in-law cautioned you about me!” The audience had a good laugh.

Women were always buzzing around Abbas, trying to snare him. He was undoubtedly courtly, but I am not sure he was a ladies’ man. Rather, he gave off a discreet noli me tangere signal, underneath the cordial manners. I learned from a documentary about him that he liked nothing better than to go off alone to remote places in nature, where he would take photographs (a medium he came to like more than motion pictures, possibly because he could practice it by himself) and write poems. He knew hundreds of Persian poems by heart, and published five volumes of his own poetry. Not the typical film director, in this respect as in so many others. His publisher and best friend said that Kiarostami confided in him that he had felt lonely all his life, though is there really any contradiction between a person of great sensitivity’s sense of loneliness and his desire to go off and be alone?

I said earlier that he died unnecessarily. The obituary in The New York Times got it wrong, saying the cause of death was cancer. Here is what I learned from Kiarostami’s champion, the film programmer Peter Scarlet:

He went into a hospital to have an intestinal polyp checked. The doctor, whom he trusted, left for Norouz (New Year, first day of spring) holiday, and had an assistant handle ‘this simple job.’ But both overlooked the fact that Abbas, who had had heart surgery a year earlier, was still taking blood thinners. So after the surgery, they couldn’t stop the bleeding. Yes, normally a polyp is checked not with surgery but with a colonoscopy. But for the same thing, they cut Abbas open. Finally, after weeks in ICU, to the relief of his friends, he was flown to Paris, where it was too late to save him. Now the motherfucking medical people in Iran, who are saying they can’t discuss the case because it’s a ‘medical secret,’ are blaming the French doctors!

So ended the life of the noble filmmaker Kiarostami at age 76. We, sitting where we are, might second-guess his decision to trust the Iranian medical system; but it was characteristic of his attachment to his country. For all that he had started to make more and more of his films abroad, he still identified with Iran’s ancient culture and with its contemporary people. He loved trees, and as he said, you don’t uproot a tree.