Remembering Robert Stone

The novelist possessed his characters, and was possessed by them

Robert Stone, who died on January 10, was a member of the all-but-vanished tribe of hard-living, two-fisted, wildly ambitious American novelists who grew up in Hemingway’s slipstream. In the 1960s, when Bob was writing his first novel, Hall of Mirrors, the elders were guys like Norman Mailer, William Styron, Saul Bellow, and Nelson Algren. They punched like heavyweights. They swung for the fences. They all stalked that shaggy beast, the Great American Novel.

Or so it seemed to an impressionable younger writer like me; I felt just enough younger to have missed out on something. Perhaps I romanticized the generation of writers ahead of me, but from the safety of the academy—I was on path of the writer-teacher—they did seem larger-than-life: more adventurous, more daring, more glamorous that the rest of us would ever be.

By the time I met Bob, he had already won the 1975 National Book Award for his second novel, Dog Soldiers, a thriller that linked the disastrous war in Vietnam with the drug culture that was epidemic on the home front. That book is richly populated with the kinds of characters who would become familiar to his readers: the druggies, the drunks, the psychopaths, the world-weary, the desperate, and the deluded, some of them so violent, cruel, or just plain loony that they could strike fear in your heart. Some critics took Bob to task for what they perceived as a darkly distorted view of humankind, but sheltered as I might have been, I believed that his vision of a dangerously out-of-control America was accurate, and prophetic.

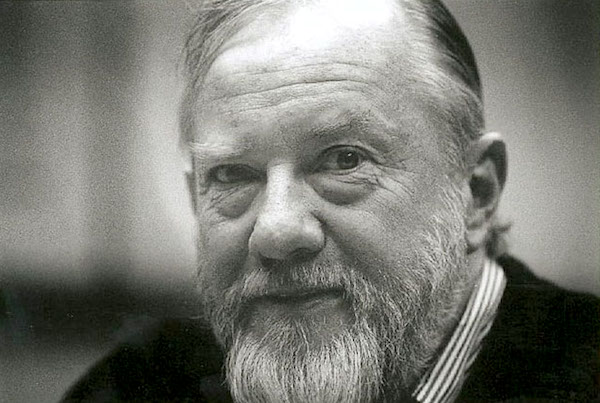

In the spring of 1983, Bob came to read at George Mason University, where I still teach, and I picked him up at Dulles. Every time I saw him, I had to smile a little: Bob was a dead ringer for Tolstoy. Same white beard, same fierce eyes, same straight hair worn close to the skull, same sanctified potato nose. He was not an imposing man but you knew at a glance that you did not want to cross him. On the plane he’d had a few belts, and since it was mid-afternoon, we went to a bar to meet Richard Bausch, fellow writer and nonpareil storyteller, to have a few more.

The whole of happy hour stretched before us and we put it to good use. Bob talked about hanging out in Mexico with Nick Nolte during he filming of Who’ll Stop the Rain, the movie based on Dog Soldiers. “His idea of a good time,” he said, “was to drink a bottle of tequila and lie down in the middle of the main street and see what happened.” If memory serves, Bob judged this to be “a capital stratagem.” The more he drank, the more eloquent he became. We must have gotten louder, too, or expressed unwelcome opinions, because the citizens at the next table began to mutter and then told us to pipe down.

“Kind sirs,” said Bob, a semi-Shakespearean voice coming to him in a twinkling, “’twas not our purpose to give offense but to entertain, and only ourselves; and if our mirth hath spilled over, why then, you are welcome to the overflow.”

This further riled them.

“I am a peaceful man,” Bob said, “but your words do buzz about me, and sting. Oh! Ow! I am pricked! I swoon! I stagger!”

And so he did. I am guessing at the words, but not at the performance. Bob did stand and deliver, and he did stagger. He stayed in character, and the tension somehow went out of the confrontation, maybe because the other guys were simply dumbfounded. They shook their heads, shrugged heir shoulders, and went back to their own business.

There was still the reading to get through. By the time we got to the packed hall where Bob was to speak, he seemed as muddle-headed as I was. I took my seat and expected the worst—but Bob came alive. He performed brilliantly. I have read that some actors have the ability, no matter how much they have drunk, to take full command the moment they set foot on the stage. As I listened to Bob read a story that required a variety of accents, including a fruity, fluty Irish-Indian hybrid, I could only marvel. He was as composed and majestic as Olivier.

Over the years I saw Bob pretty regularly, but whatever insight into the man I have dates from that night. The ease with which he could invent a character on the wing and slip into another role—this wasn’t just a matter of performance. It was uncannier than that. When Bob inhabited another character, he possessed that character, or was possessed. There in the bar, and later at the podium, his whole aura had changed. In fact, when I spoke to him only seconds after his presentation, he could barely put two words together, as though his whole being had depended on sustaining that illusion of another character.

To some degree, all novelists must be able to enter their characters, and perhaps I am reading too much into that night. I have undoubtedly embellished that memory in many retellings, but my conclusion stands: something eerie happened when Bob got into another character. He was gone.

Other people, including those he had only imagined, were entirely real to him. We were both involved with the PEN/Faulkner Foundation (Bob was the chairman of the organization for 30-plus years), and I saw just how generous he was, how loyal, and how tender. Any report of suffering could bring tears to his eyes. Having been raised by a schizophrenic mother, having spent many years in a Catholic orphanage, Bob knew the pain of abandonment and loneliness. The way he made it bearable for himself, or so I have come to believe, was to invent stories.

That ability—that need—to lose himself in his stories remained with him. His emotional and psychic investment in his characters is absolute. For me this has come to stand as the essential quality of his work, the quality that makes his fiction so moving. His characters might be drugged out, violent, or deluded, but the reader who does not turn away will come, slowly and perhaps painfully, to sense the balance tilting toward mercy. These characters have souls. They might never be redeemed, they might be beyond forgiveness, but their creator finds himself in them, and he loves every anguished one of them.