Editor’s Note: February’s school shooting in Parkland, Florida, has come to dominate the national debate over gun rights, and rightly so. But our memories of earlier massacres, such as the one at the First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, Texas, last November, often fade troublingly quickly, as our attention is overtaken by fresh horrors. In Sutherland Springs, 26 people were shot to death during a church service, and another 20 wounded, when 26-year-old Devin Patrick Kelley opened fire with an assault rifle. What follows is a writer’s chronicle of how, in the days and months that followed, a community dealt with the magnitude of its loss.

November 5, 2017

When word of the massacre reaches me on a bright Sunday afternoon, I’m drawn into social media and the live news coverage. By evening, it’s time for another shooting conversation with our kids. Our 15-year-old daughter asks, simply, “Why?”

I could speak of evil and complicity. I could bring up mental health, culpability, and how, collectively, Americans own 270 million guns. I could talk about broken laws, politicians in lobbyists’ pockets, and apathy. Instead, I say, “I don’t know.”

That night, I think about how one of my college professors had said that our lives are framed by war. We can say the same about mass killings. Remember San Ysidro, Killeen, Columbine, Goleta, Virginia Tech, Fort Hood, Aurora, Sandy Hook, Navy Yard, San Bernardino, Charleston, Orlando, Las Vegas. And now Sutherland Springs, only 25 miles from our house and, until today, one of those places we never noticed on our way to somewhere else.

November 9, 2017

I walk the aisles of the sporting goods store where the killer bought the gun, the same place where we buy our kids sneakers and baseballs. Between the fishing poles and compound bows, AR and AK assault rifle accessories fill the shelves—30-round mags ($12.99), 42-round mags ($14.99), rail grips ($18.99), red laser sight ($29.99). Cases of AR ammo—420 rounds of 5.56mm for $189.99—fill the next aisle. The Ruger AR-556 semiautomatic rifle, the kind the shooter used, costs $649.00, plus tax.

“CSM to the gun bar for a gun sale,” the intercom announces. The gun bar runs along one side of the store under a red, white, and blue FIREARMS sign. Long guns fill a rack on the wall, and handguns fill glass display cases. Customers take numbers and wait. I look on as a dozen middle-aged men and women from San Antonio’s suburban sprawl stand in line, waiting to buy weapons. They listen for their numbers to be called as, overhead, store speakers play “Stairway to Heaven.”

November 10, 2017

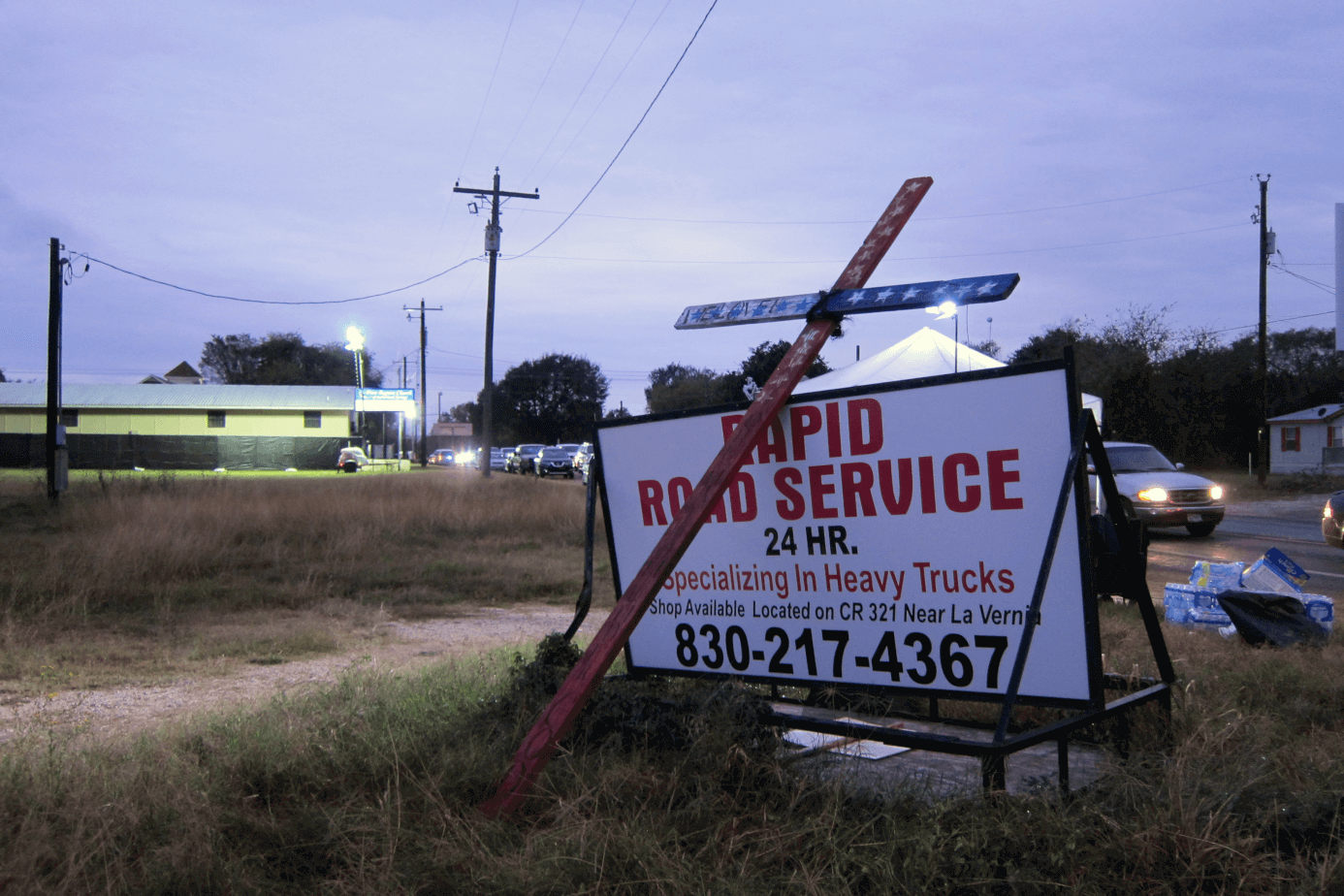

At the town line, not far from the Gunn Creek bridge, a lone purple ribbon waves from the Sutherland Springs sign. Semis and horse trailers roll through the intersection of Highway 87 and Farm to Market Road 539. The First Baptist Church sits on the south corner, near the site of a makeshift memorial. Only three satellite trucks remain where dozens had clogged the shoulders 48 hours ago. News crews chat in low tones, smoke cigars, and eye those standing before the wooden crosses near the corner. People stare at the names, photos, flowers, stuffed animals, balloons twisting in the breeze, and stacks of fresh bouquets atop older ones. The mourners kneel, hug, cry, hold hands, shake their heads, and look at their feet. A “Billy Graham Rapid Response Team” car arrives and people in Red Cross vests wander about. A jogger carrying a large American flag runs past, while nearby in the dirt, an orange-and-white cat crouches, licking a Styrofoam container of leftovers.

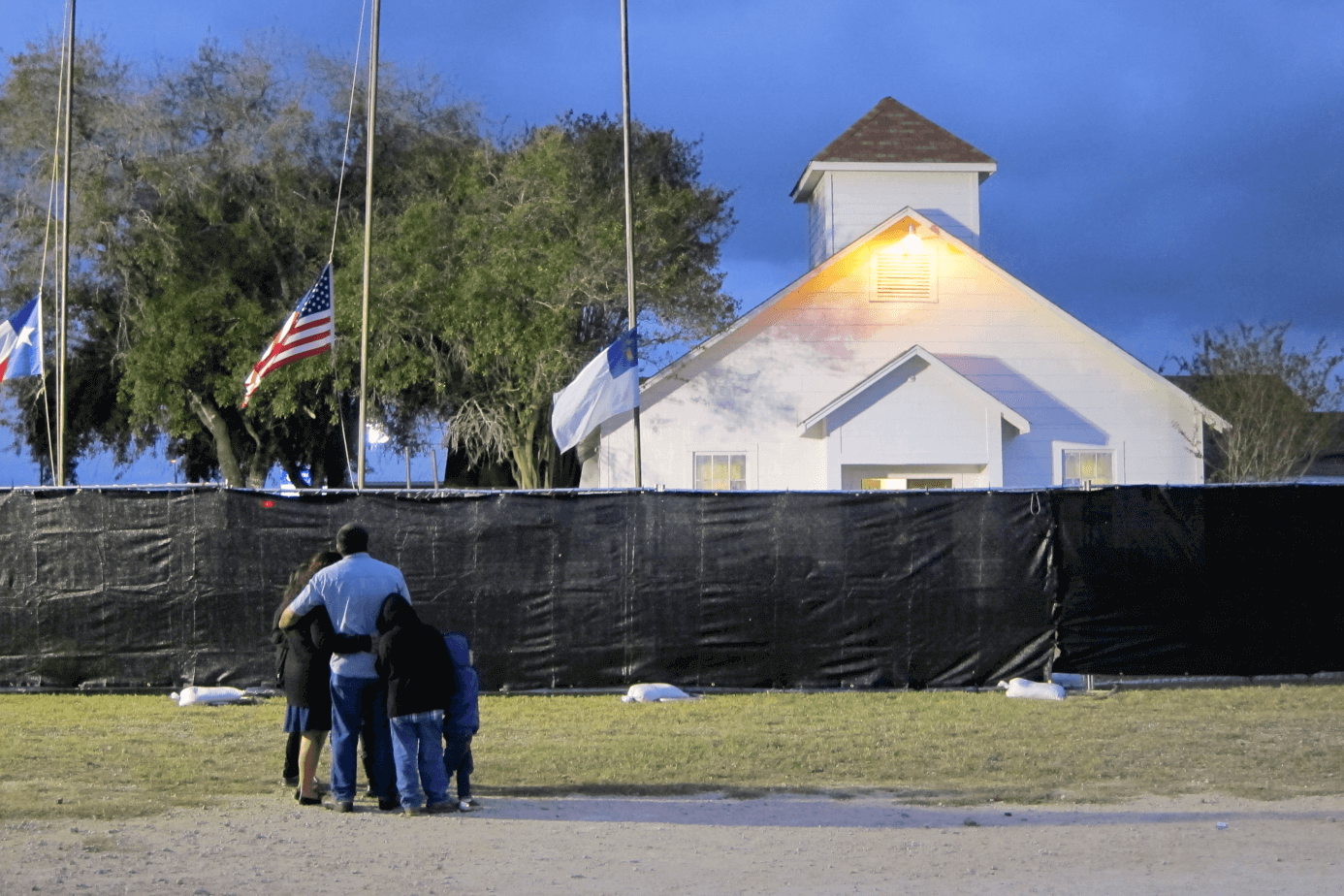

A chain-link fence covered in black mesh shrouds the church grounds. Three half-staffed flags and the low steeple rise above the barrier. A blue-and-white sign out front still reads: “JOIN US, FALL FEST, OCT 31, 6 TO 8 PM.” Squares of tape cover bullet holes in the stained-glass panes. People stare at the fence with crossed arms. One guy snaps a selfie. A mobile command post hums from behind the fence. Wilson County Sherriff’s deputies stand near a gate, while members of a controversial right-wing militia group called the Oath Keepers patrol the perimeter. People speak softly and move slowly, intentionally. The church door opens, and from inside, I hear what sounds like people scrubbing the floor.

November 11, 2017

From the north, I cross the limestone green Guadalupe River and pass grazing horses, crumbling barns, cattle, an RV park, Good Luck Road, and Sweet Home Road. Words from the mouth of Flannery O’Connor’s Misfit come to mind: “No pleasure but meanness.”

Ten miles from the church, at the corner of 539 and Sandy Elm, there’s still evidence that the shooter died here. Orange spray paint highlights where his car’s tires left the pavement. Pink marker flags show the vehicle’s path and resting spot in a field dotted with hay bales. But the barbed-wire fence has already been repaired. Soon the rain will wash away the paint, and someone will pull the markers.

A father plays ball with his son within view of the crash site. Farther on, a man jockeys his riding mower, and a University of Texas flag flies above a pasture filled with massive Longhorns. I catch a whiff of crude and pass historical markers for Linne Oil Field, Polley Cemetery, and finally Pat Higgins’ Grass Farms. Then over Cibolo Creek, up a small hill, and I’m in Sutherland.

The sky’s dark, and it’s raining just enough to notice. One news vehicle remains. The chapel lights shine against the ashen sky, and an industrial fan stands in the doorway. Tomorrow the church will reopen as a memorial. Visitors will pass a 150-pound wooden cross, displayed at the makeshift memorial on the corner, which a man carried on his back from New Braunfels, a distance of 40 miles.

There are fewer police officers, but members of the militia still linger about. A man tries to peak through a gap in the fence, and a female Oath Keeper yells, “Sir, sir, sir. You cannot look! You need to back up. They’re not allowing anybody close.” Members of a police motorcycle club, called The Thin Blue Line, idle their Harleys nearby. The guy next to me opens his Bible despite the raindrops and reads. A family with two small children huddles in front of the fence. A militiaman approaches and speaks quietly to the father. A boy, maybe four or five, walks through the dead weeds to the cat.

Driving home, I think of what Robert F. Kennedy said, when announcing news of Martin Luther King’s assassination: “We can do well in this country.” And we would do well to heed his challenge to “tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of this world.”

November 16, 2017

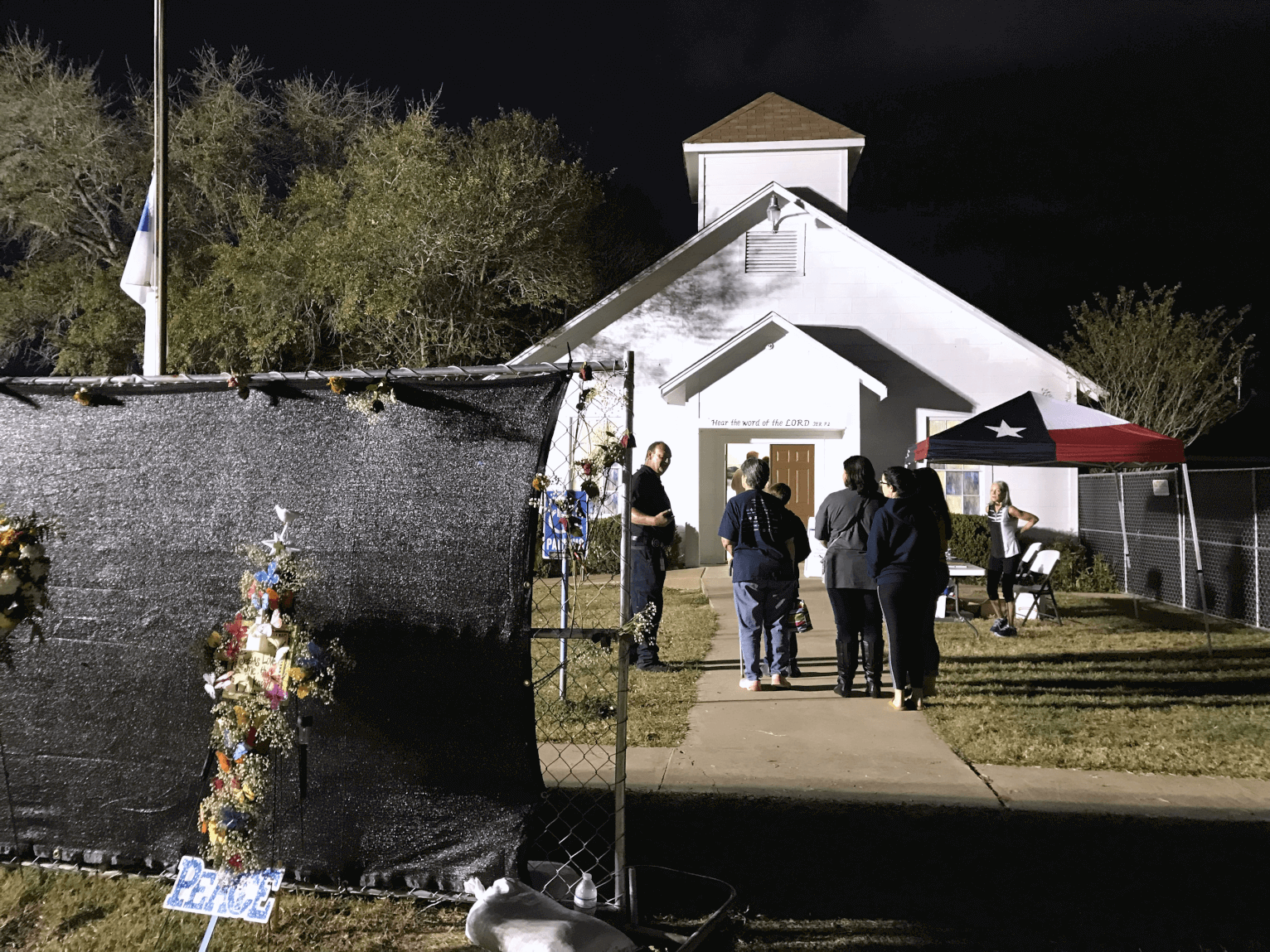

Just after sunset, driving home from a middle school basketball game, my 13-year-old son and I are approaching Sutherland from the east. I tell him that the church is now a memorial, and we decide to stop there.

The news trucks are gone, and the black fence is open. Flower arrangements stand at the entrance. Two women with a guest book smile at us from under a Texas-flag pop-up shelter. Hand-painted letters above the door read, “Hear the word of the LORD.” There’s no sign of the militia group, and a state lawman stands at the entrance. He extends his hand and says, “Welcome. Thank you for coming. You’re welcome to take photos. Just don’t take pictures of people without their permission.”

Whiteness fills the room. Some have called it a vision of heaven and others a minimalist art installation. Twenty-six white chairs—each with a single rose, red cross, and first name written on the back in gold ink—are positioned around the room where the victims happened to be sitting. We stand in the back. I place my hand on my son’s shoulder and feel guilty for peeling back another layer of innocence and security. A recording of scripture readings from past services plays on a loop, and in that moment, we’re the only ones in the chapel. In front, a tall wooden cross stands behind a podium with an oversize Bible surrounded by tissue boxes. We walk around the room silent, staring, and thinking. The stained-glass panes have been repaired. Several quarter-sized pockmarks dot the cement floor, and a crack runs under many of the chairs. On the wall, a sign: “This passage was to be read the morning of November 5, 2017, and was never heard. It will now be heard by all … Be Thankful: A psalm of thanksgiving.”

The church was resurrected in seven days. Reporters describe how the former associate pastor had a vision from God to convert the sanctuary into a place of remembrance. Volunteers removed pews, carpet, paneling, and equipment. They cleaned, patched, and painted. We marvel at the bravery of this congregation to open its doors, to allow us to look inside.

On leaving, we step out into the darkness, passing the illuminated blue-and-white sign. One side reads “LOVE NEVER FAILS,” and the other, “JESUS ALWAYS WINS.” Under the glow of streetlights, we stand alone at a row of crosses. The orange-and-white cat emerges, pausing in front of a sign reading “PEACE,” and then walks toward us. We stroke his fur.

December 27, 2017

Fifty-two days since the shooting, and the story has largely disappeared. Near the Sutherland Springs sign on Highway 87, 26 white crosses now line the shoulder. Like roadside markers for crash victims on highways across America, the display recedes in the rearview mirror, increasingly distant, then forgotten.

A few miles southwest of the church, the 158-year-old Sutherland Springs Cemetery is a small, well-maintained tract on a knoll overlooking a pond and ranchland. Near the entrance, words on the plaque carry new meaning since the massacre: “This historical burial ground is a chronicle of Wilson County pioneers and significant figures in the history of the region.” Some of the shooter’s victims are interred here with temporary markers. Their headstones have yet to arrive.

Back at the church, the black fence is gone, and a winter wind blows banners that read “Sutherland Strong” and “#VegasStrong,” which hang alongside signs and decorations honoring the dead. I’m watching visitors stroll around the chapel when two men arrive in a pickup hauling a large wooden ramp. They’re from San Antonio, and they’ve built the ramp to help one of the wounded parishioners access the stage in the new worship center. They’ve come to deliver their handiwork, and I offer to help. Minutes later, we’re in a nearby portable-building-turned-sanctuary. Christmas decorations still adorn the walls, including the words, “Joy to the world the lord is come.” We clear a path, hoist the ramp from the pickup, carefully situate it, and replace the items we moved.

Back in the chapel memorial, I visit with the volunteer caretakers—a gentle couple from New York, who traveled to Texas to help friends who are church members. They greet the steady flow of visitors with smiles, handshakes, and hugs. I hear the husband describe the shooting as demon’s work. He says the victims are dancing in heaven. A visitor tells him how thankful she is to be able to pay her respects. He understands, he says, and gives her a book, Why Forgive?

February 2, 2018

Nearly three months after the shooting, all of the survivors are now out of the hospital, recovering at home. The Gun Violence Archive reports that there have been 60 mass shootings—incidents in which four or more people are shot, excluding the shooter—since November 5, 2017. The memorial chapel still hosts visitors, and the roadside display of crosses appears more orderly and permanent. Today, the blue-and-white sign says, “Hang in there, even Moses was a basket case once.” As I stand outside the church, a lady drives up, slows, snaps a photo, and drives on. She doesn’t look back as she pulls away.

Driving north from Sutherland on 539, I see leafless trees against the dull, brown South Texas landscape. The clouds hang low, and to the west, a sliver of clear sky reveals the sun hovering on the horizon. I realize, suddenly, as if for the first time, that this is gun country, and it will never change.

April 9, 2018

Sutherland Springs will forever reside between Las Vegas and Parkland in our country’s unending chronicle of mass shootings. Hard as it is to believe, right-wing conspiracy theorists have harassed churchgoers since the shooting here, online and in-person. As with previous mass shootings, they call the tragedy a “false flag” operation—a staged event meant to influence public opinion against gun ownership. In March, a couple confronted the pastor outside the church, denying the existence of the dead and demanding to see their birth certificates. They were arrested after vandalizing church banners. Despite this, Sutherland continues to heal, having recently unveiled plans for the construction of a new church complex.

Las Vegas and Sutherland came and went without any prolonged national discussion about gun rights, background checks, mental health, or other actions to curb such violence. But the Parkland shooting sparked the most significant reconsideration of gun rights since Sandy Hook, with hundreds of thousands of people taking to the streets in Washington, D.C., and across the country. It’s worth asking, why did earlier shootings fail to spawn such a powerful reaction? The answer, I think, is a confusing mix of timing, geography, demographics, and politics. The tragic irony of Sutherland Springs is that, far from motivating local people to reconsider gun laws, the shooting has only emboldened their support for guns as personal protection—a strange but revealing example of how different people in different parts of the country react to gun violence. But somehow with Parkland, much of our society has reached a critical mass where we realize, finally, that thoughts and prayers of the kind that are always offered after mass shootings, however well meant, will never be enough.