When some notable person whom you knew, however slightly, dies, you may find yourself perusing the obituaries and eulogies and disagreeing with this or that characterization. So it was last week when Robert Silvers, longtime editor of The New York Review of Books, passed away. The headline in The New York Times called Silvers “self-effacing.” and the obituary’s writer, William Grimes, after using that term, went on to say that “it was Mr. Silvers who came to embody The Review’s mystique, despite, or perhaps because of, his insistence on remaining a behind-the-scenes presence, loath to grant interviews or to make public appearances.”

The Bob Silvers I knew was no shrinking violet. He was an extremely proud, self-confident man, completely aware of his stature, achievement, and power, and willing to represent The New York Review of Books at any public event. If he was loath to grant interviews, it was probably because he considered them a bore. Everyone remotely attached to the book world knew who he was, admired him, worshiped him, resented him, or feared him. What the obituarist took for self-effacement was in fact a reserved, impersonal manner—the Anglophile side of Silvers, which went with his tailored gray suits, his refined taste for the good things in life, and his insistence that anyone writing for the publication keep a tight rein on their personal effusions.

I first came into contact with the man when I was working for Teachers & Writers, a nonprofit agency that sent writers into the schools to renovate the language arts curriculum. Herbert Kohl, an educational reformer (author of 36 Children) had roped his sometime publisher Silvers into serving on T & W’s board. This was during the ’60s, and it was typical of the progressive Silvers that he would support idealistic causes like revolutionizing public schools for inner city minority youth—albeit from a safe distance. After a short period, he never attended T & W’s board meetings, but continued to permit his name to appear on the organization’s masthead.

When T & W commissioned me to edit an anthology about the organization on its 10th anniversary, I requested an interview with Silvers about the early days and his involvement in it. The NYRB was then still located in the General Motors Building on West 57th Street, its offices cheek by jowl with law and accounting firms along an endless drab corridor of frosted glass doors. I found Silvers in shirtsleeves and tie, smoking the sweet-smelling dark cigarillos he then fancied, surrounded by precarious piles of books and manuscripts. He dutifully obliged with his time but was at bottom unforthcoming, recounting the history of T & W’s founding (which I already knew) in an objective, impersonal manner. There were no human-interest anecdotes. I, who prided myself on an ability to establish a warm connection in any one-on-one conversation, had to admit defeat. In the face of this rather opaque personage, I was left to question if he took me in at all, and I was equally baffled by getting not even a peek at his inner life.

Meanwhile, two of my books were reviewed in the NYRB. The first, Being with Children, may have attracted his nostalgic approval because of its emphasis on the work I did with Teachers & Writers; the second, my novel The Rug Merchant, was suggested to him by the critic Robert Towers, an acquaintance of mine. Towers also recommended me to Silvers, who was looking for possible fiction critics, as a reviewer. My dream was to write for The New York Review of Books, so naturally I was excited at the prospect. I was sent two novels for a tryout; the novels were wildly different, but I did my best to knit them together in a coherent essay. I thought the results decent, but Silvers took a pass. I later learned that he wanted more plot summary, which I’d been averse to giving in a critique. It would seem that the typical NYRB reader preferred not to have to read the book under review, but to get enough of a sense of its contents to chat about it.

A few years later, having fallen under the thrall of the Japanese novelist Soseki Natsume, I proposed to Silvers that I write a consideration of the dozen Soseki novels that were translated. “We already have our Japanist,” he told me coolly. Whatever. It finally dawned on me that there was a club of NYRB writers: the same names kept recurring again and again. I suspected that new contributors could be brought into the club only by social introduction, and if you did not have the proper entry, you did not exist on his radar and would never get in. I tested the waters one more time: running into Silvers at a library event, I mentioned that I was working on an introduction to the reprint of William Dean Howells’s New York novel, A Hazard of New Fortunes. “Send it to me,” he said. I did, nothing came of it, and soon after, a piece by Arthur Schlesinger Jr. appeared in the NYRB: his introduction to a competing reprint of A Hazard of New Fortunes.

The sense of snobbish exclusion cut bitterly into my gut. It was that classic literary world resentment: Why not me? For whatever reason, no matter how much my writing was welcomed elsewhere, I was not to be accepted into this happy band of august arbiters. Was I too rough around the edges? Too Brooklyn, too personal essay-ish? Too unconnected to the Upper East Side/Upper West Side/London social circles in which Silvers traveled? What made it harder to take was that I could not disparage the rejecting organ because I loved to read The New York Review of Books. I found it indispensable to my well-being. An early subscriber, remembering the excitement around its first appearance in 1963, I had not missed an issue in decades. Of course some issues were duller than others; but almost always I read the publication cover to cover, and came away stimulated and enlightened by something in it. It was and is the standard bearer for American intellectual life: a unique repository of thoughtful discourse, unrepentantly highbrow, in a culture increasingly given to dumbing down.

Over the last five years, I have become a regular contributor to the NYRB. How did this happen? Edwin Frank, the publisher of the equally indispensable NYRB Classics, asked me to write an introduction to a novel by the 19th-century German novelist Theodor Fontane. Frank would routinely submit these introductions to Silvers, who would reprint the ones he liked best. He chose my Fontane introduction, and also one I did about the English writer Max Beerbohm. I proposed to Silvers an appreciation of the American essayist Edward Hoagland, and this time he accepted the suggestion. From that point on, every few months he would commission another article. He never discussed them with me in advance: a package would simply show up in my mailbox which contained one or more books, with a brief note saying he hoped I would find them interesting enough to review, and a mention of the fee. The pay was excellent, and so I accepted them all, not wanting the flow to stop.

The assignments were a catch-all of novels, poetry, and essay collections. I still was unsure he really “got” me, knew what my range of interests were, but clearly he now trusted me. I was in the club. Contrary to what I had heard, Silvers’s editing of my pieces was extremely light: either he had given up the old battles over each comma and word usage, or I turned in copy that was more or less camera-ready. You might say that from my over 50 years of reading the NYRB, I had so assimilated the house style that I could merge my own essayistic manner with its slightly formal, authoritative tone.

I reviewed books by Charles Simic, Joyce Carol Oates, Mischa Berlinski, Tim Parks, Cathleen Schine, Jane Jacobs, and Eli Gottlieb. All but Gottlieb were regular contributors to the NYRB, which made writing about them a tricky proposition. The common jibe was to call the periodical “The New York Review of Each Other’s Books,” and it was true that Silvers loyally assigned reviews of his contributors’ new publications; but I (compromised perhaps by now being a beneficiary) no longer view this as necessarily a corrupt payback. It may simply have been that he regarded his contributors as worthy authors, and so why punish them by neglecting their latest work? Practically speaking, I knew it would not do to savage any of the regulars’ books in my review, and in any case, as a fellow writer who realized what labor it took to compose a book, it wasn’t my style to pen vicious pans of anyone. So I drew on a measured, tactful, balanced tone, but when criticism was called for, of course I had to be honest. For the most part, Silvers accepted my judgments without demurral, though I could tell it pained him when I wrote a mixed review of Oates’s three books. He called me at home a few times to make sure I had got some historical facts about the Tawana Brawley case right, without coming clean and admitting that he wished I could have been more positive about two of her three books. Only when I used a review of a Jane Jacobs biography to question some of her premises and methods did he respond with alarm, saying that I had been too mean to “our Jane” and was not sure he could run the piece. I asked him for a chance to take another crack at it, which he gave me, and I toned down some of the criticism while buttressing my argument with more evidence. He thanked me for my work, sent me a check, and said he still had some concerns, but the implication was that he would run the piece eventually. With his death, it remains in limbo.

A friend of mine who wrote regularly for the NYRB counseled me that Silvers retained considerable nostalgia for the heroic protests of the ’60s, and Jane Jacobs, being one of the prime voices of that movement, may have been in his mind a sacred cow. This same friend also thought Silvers was much more engaged by public affairs, political ideas, and burning social issues than with literary aesthetics. (I agree.) He said Silvers would sometimes have long phone conversations with him about the latest turmoil; the editor had a taste for gossip about these matters. I kept that in mind when I had lunch with Silvers about a year ago. I had requested this face-to-face repast because it seemed odd that our dealings were taking place entirely through the mail and the Internet. Also, I was curious how well we would get along.

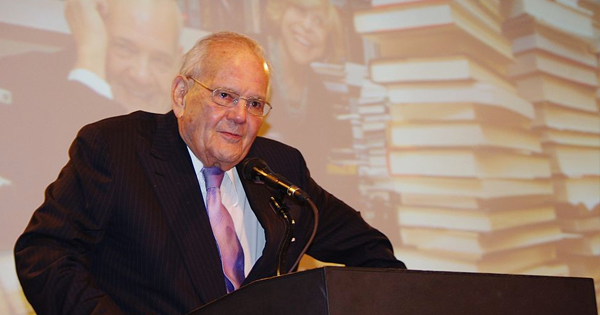

The NYRB’s office had moved downtown to a Greenwich Village townhouse, a cozier setup than their former digs. I stopped by to gather Silvers, and we went nearby to a Japanese restaurant of his choice. He looked healthy and in good form, and our hour-long conversation ranged over history, politics, the arts, and urban affairs. He seemed knowledgeable about everything, and I came away thinking him one of the smartest, most interesting guys on the planet. This time I perceived a warmth, a gusto for life, and a quiet humor underneath the reserve. He still didn’t talk much about himself—he obviously didn’t like to go in for such intimacies—but when speaking about other subjects he was fully engaged, fully present. His interest in the world was who he was; consequently, there was no question at all of self-effacement.

I realized I’d probably been getting him wrong all my life—thinking him stuffy and snobbish because of my own insecurity. I regretted having lost the chance of his becoming, if not a friend, then a stimulating acquaintance; I had started in too late to get to know this remarkable man. Of course, I realized full well that it had never been up to me: I could not have struck up an acquaintance with him until he gave me the nod, the exquisitely belated signal, that I could be considered a member of the club.

My memory of him as so mentally sharp and physically vibrant at our comparatively recent lunch keeps returning in the wake of his death. I had known he was ill, in and out of the hospital with pneumonia, these last few months, and that the illness had begun around the time when his companion, Grace, the Countess of Dudley, had died in Lausanne, Switzerland. Some of his writers thought he had lost the will to live when she passed away; but I am a firmer believer in the germ theory of illness than in the idea that people die of heartbreak. Moreover, it must have taxed him considerably, at the age of 87, to keep making those transatlantic flights. I was told he still insisted on editing pieces in the hospital. He did not like to delegate, was no good at it. Even at the gates of death he was loath to name a successor. He had wanted to go out as the working editor-in-chief of The New York Review of Books, and he has had his wish, and now we wait to hear who will take his place, if anyone indeed can be expected to fill his shoes.