Rooms With a View

A childhood in Haifa—before Israel attained statehood and just after—helped form an architect’s vision of what an ideal home should be

As I reach further into my 80s, traveling around the planet several times a year, I think of the long journey that brought me improbably from Haifa—the city of my birth—to the adventure in architecture I have pursued for six decades.

During my childhood, Haifa was administered by the British under the Mandate for Palestine. It lies at the southern end of a long crescent bay, and on the waterfront was the port, built and controlled by the British. It extended eastward toward the bay, where the Iraq-Mediterranean pipeline had its terminus. Along the port was the main downtown boulevard, then known as Kingsway, now Independence Road. Immediately behind this was the lower city, or the Old Town, as it was known, its architecture mostly Arab-Mediterranean vernacular, with narrow streets and crowded markets. A wafting aroma of spices and meat roasting on wood fires filled the air. The architecture was stone—warm and Mediterranean, vaulted and domed. Since childhood, I have loved domes. There is a spiritual element, I am sure—circularity symbolizes unity—but a practical, evolutionary aspect, as well: in desert regions without many trees to provide wood, domes built of brick or stone are the only means to span a large room.

Upward from the Old Town, then as now, the city changed color and character as it rose in elevation along Mount Carmel. Midway up the slopes was a neighborhood, Hadar HaCarmel, of white Bauhaus-style buildings. At the center of Hadar HaCarmel was the campus of the Technion—today, Israel’s equivalent of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In contrast to the stark, modern simplicity of the Bauhaus style, the Technion was a domed, symmetrical, winged structure built with buff stone arcades—a European attempt at Romantic Orientalist architecture. Farther up the hill were the Bahá’í Gardens, the holiest place for the Bahá’í religion, where its founder is buried. I thought of these gardens in my youth as the most beautiful place in the world—the embodiment of paradise. Finally, at the crest, with extraordinary views over the harbor and the city, stood a precinct of landscaped villas and low apartment buildings that was thick with pine trees. To this day, every time I smell pine, I think of Haifa. It remains a beautiful city.

My father, Leon Safdie, had come from his hometown of Aleppo, in Syria, in 1936. He imported textiles, quality woolens, and cottons from England and fabrics from Japan and India for the local markets. My mother, Rachel Safdie, née Esses, was English. She too came from a Jewish family with roots in Aleppo, but hers had emigrated to England at the turn of the century, settling in Manchester. My mother was born in that city and had a strong Mancunian accent all her life.

In 1937, my mother, age 23, traveled from Manchester to Jerusalem, where her sister Gladys lived. Disembarking at the port of Haifa, she almost immediately met a young man who had an office near the docks. She married him a month later, and I was born the following year, on Bastille Day 1938. My father spoke Arabic and a poor Hebrew, though he was fluent in French; aside from English, my mother knew a little French. They did not at first even have a strong common language.

The Jews of Aleppo were broadly known as Mizrahi, or Eastern Jews, but most of them also claimed to be Sephardic—that is, descended from the Jews expelled from Spain and Portugal by the Inquisition at the end of the 15th century. (Sepharad is the Hebrew word for Spain.) But Aleppo’s population also included many Jews whose ancestors had never left the Middle East. The Sephardim spoke Ladino, a Spanish dialect, though in time the old Middle Easterners took on Ladino as well, making the distinction between the two groups difficult to ascertain. In the world of Jewry, strongly divided into Ashkenazi (European) and Eastern Jews, the Jews of Aleppo, no matter what their actual origin, belonged to the Eastern group. My own family came originally from the town of Safed, in Galilee—hence the surname Safdie, variants of which (Safdié, Safadi, Safdi) can also be found among Muslim, Christian, and Druze families. Sometime during the 16th or 17th century, driven by the economic decline of Safed, many Jews had moved north from Galilee to Aleppo.

In Haifa, my family lived at first in a three-story Bauhaus-style apartment building in Hadar HaCarmel, which was home to much of the city’s large Jewish community. I went to kindergarten on the campus of the Technion and recall being allowed to walk there by myself at the age of four or five, my mother watching from the balcony as I crossed Balfour Street onto the campus. At this early age, I already enjoyed a sense of true independence, a feeling that would become even more pronounced in my teens—an experience familiar to many Israelis of my generation.

The onset of the Second World War provides some of my earliest memories. On Friday evenings, we hosted Jewish soldiers from the Australian Army for Shabbat dinner. We went down into the air raid shelter in the basement of the apartment building almost nightly. I remember looking with excitement at the giant silver barrage balloons that were launched above the bay, tethered to cables that served as obstacles to air attack. I remember stone towers along the waterfront emitting smoke to camouflage the oil refinery, which was the main reason Haifa was an enemy target to begin with. Luckily for us, the enemy wasn’t the Luftwaffe—it was the Regia Aeronautica, and though the Italians did score a couple of hits and inflict some damage, they never landed a crippling blow.

Unlike Haifa, Jerusalem was never bombed during the war. To escape the dangers of the coast, my own family stayed there for an extended period in 1940, in the home of my aunt Gladys, her husband, and their four children. It was during this time that my brother, Gabriel, was born. Traveling from Haifa to Jerusalem was a major undertaking in the early 1940s—four or five hours by bus on dusty roads, stopping now and again for breaks and refreshments at little shops offering falafel, orange juice, and sandwiches.

I did not enjoy staying with my aunt and uncle. Their home was small and crowded, and they were very religious and deeply observant, which my own family was not. They were also aggressively zealous. My uncle, an imposing figure, once offered to give me a pound sterling if I promised not to use electricity on Shabbat for an entire year—this was back in a day when a pound was worth four dollars. I can still see the silver coin in his hand. But I declined the offer. Judaism and spirituality weave through my life in important and distinctive ways, but the implacable religiosity of my aunt and uncle’s family—their attempted imposition of orthodoxy—served only to fortify my resistance.

Jerusalem itself I loved, especially the Old City, with its narrow passageways and up-and-down steps everywhere. I wandered the souks, with their spice counters and local crafts. The almost orchestral hum of languages and dialects was matched by the diversity in forms of dress—Muslim women covered modestly in many colors, British soldiers in khaki shorts, religious Jews in black, English women in floral hats. The sonorous tolling of church bells punctuated the Muslim call to prayer—this at a time when the call to prayer still came from an actual muezzin in a minaret, a man of flesh and blood, rather than an amplified recording. The Western Wall, the last surviving remnant of the Second Temple, was at the time accessible only by means of an alleyway, perhaps 15 feet wide, sandwiched between the Temple Mount and the Mughrabi (or Moroccan) Quarter. For a Jew, visiting the Western Wall in effect meant negotiating a canyonlike passage through an Arab neighborhood. The tension was palpable. One never knew when trouble would start—stone throwing, sometimes worse. But throngs of Jews could always be found praying at the wall—men mixing with women, unlike today.

Outside the ancient city walls was an emerging modern downtown. The elegant King David Hotel, its tall Sudanese doormen resplendent in red turbans, overlooked the Old City. From the terrace in back you could see the city walls, the golden Dome of the Rock, and beyond the city itself the Mount of Olives. Ben Yehuda Street bustled with cafés and shops. Jerusalem to me felt very cosmopolitan. The British presence was inescapable—officials, soldiers, businesspeople. So was the old Arab aristocracy. Jewish life revolved around the Hadassah Hospital, the Hebrew University, and the Jewish Agency, the precursor of the government of Israel.

After Israel achieved independence in 1948, and for two decades thereafter, until Israel’s victory in the 1967 Six-Day War, Jerusalem was divided, and the Old City was inaccessible to Jews from Israel. But in the early 1940s, when I first knew it, the city was a unified place. As a rule, we went to Jerusalem twice a year. Every summer, we also traveled north to Lebanon. Much of our extended family lived there, having moved to Beirut from Aleppo. My sister Sylvia was born in Lebanon during one of those trips—another extended stay prompted by wartime conditions. This time the worry was close to panic, though I am aware of that fact only in retrospect. The panic had to do with the advance of German general Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps across the Libyan Desert, toward Egypt. Would Palestine be next? We stayed in Lebanon until 1942, when English forces in Egypt blunted the direct military threat posed by Nazi Germany.

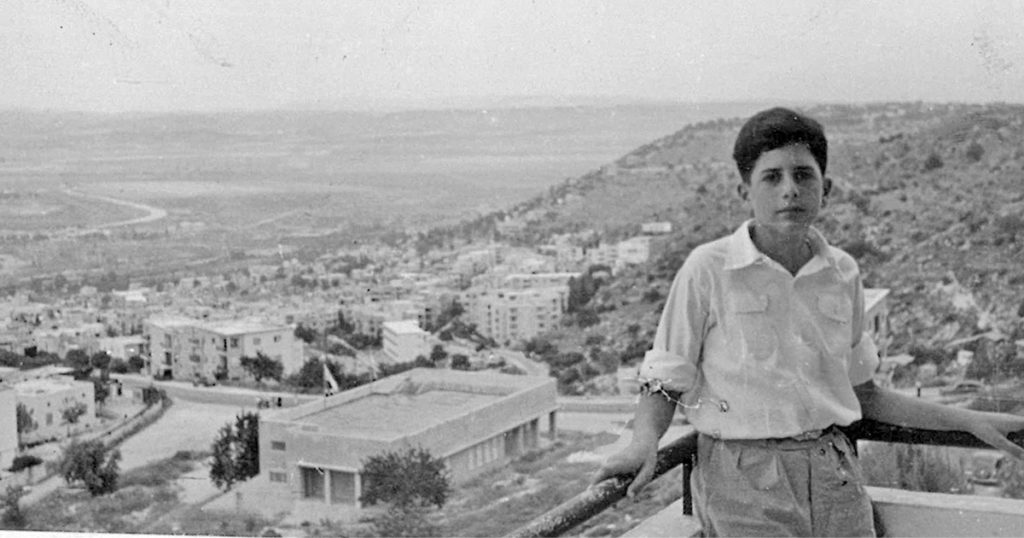

A view of Haifa from the slopes of Mount Carmel—where the author lived as a child—in a photograph taken in the 1940s. (From If Walls Could Speak)

For my family, the war years turned out to be good for business, as my father was able to continue importing goods that were shipped from India by my uncles. My parents bought an apartment building on Mount Carmel. We went to Beirut and bought a car. And it wasn’t just any car. It was a 1947 Studebaker Commander, with its radical new design by the brilliant Raymond Loewy, ivory in color and sensational to behold.

On that trip in the late summer of 1947, we ventured farther than usual, to Aleppo itself, the only visit I ever made to that city. Our extended family, children and adults alike, piled into three Chrysler limousines and drove north from Beirut to see my grandmother Symbol, fragile and petite. We visited the ancient citadel of Aleppo, an imposing medieval structure on a site that had been fortified for four millennia. Memorably, my uncles panicked when they realized that my brother and I had badges sewn onto our shirts. The badges showed the profile of the Reali School, which we attended, and were embroidered with the words vehatznea lechet, meaning “proceed with humility.” Because the Hebrew letters marked us as Jews, the adults were fearful of letting us into the streets. Tensions ran especially high in the Arab world during those last days of the British Mandate for Palestine. The countries of the newly established United Nations were at that moment deliberating whether to form the State of Israel, which by its nature would have life-changing consequences for everyone in the region. In the end, my uncles ripped the badges off our shirts and told us not to speak Hebrew in public. We fell back on English, our other language.

Palestine had been in a state of civil insurrection for several years as Jewish fighters for independence waged a guerrilla campaign against British authorities. Our family was in Jerusalem in July 1946 when the Irgun, the militant underground Zionist organization that believed in violence as a tool of persuasion, exploded a bomb in the King David Hotel, where Britain maintained its Jerusalem headquarters. I was a child of eight, standing with my cousins at the Jaffa Gate at that very moment, looking west. We saw the flash, and a second later the horrifying sound reached our ears. Scores of people—Britons, Arabs, Jews—were killed.

The United Nations agreed to the creation of an independent Israeli state on November 29, 1947, partitioning Palestine, at which point the conflict with Britain broadened into a conflict between Jews and Arabs. By springtime, the Battle of Haifa was underway, as the Haganah, the nucleus of the Israeli military, sought to gain control of the strategically important city, which was in the area designated for a Jewish state. From our home high up the slope, overlooking the port, we could hear the shooting. After stray bullets came through a window into my bedroom, we erected defensive steel plates on the veranda and windows. It is said that after the battle of Haifa, the message from the Jewish victors to the Arab population from loudspeakers mounted on cars was encouragement to stay in the city—and quite a few Arabs did stay. My parents had Arab friends. Haifa today is probably one of the more successful mixed communities of Israeli Jews and Arabs. But tens of thousands of Arabs, understandably fearful, left the city in 1948, fleeing to Arab towns farther north and to Lebanon and beyond.

My recollections of this exodus are firsthand and troubling. With my friends, we watched as much of the Arab population picked up and left—and then watched Jews from the poorer abutting neighborhoods enter the Arab neighborhoods and start to loot. They would go into houses, pull out drawers, and empty the contents. People often departed very quickly, leaving silverware and other goods behind. I saw someone take off with a stamp collection. At this young age, I already felt that life was taking a turn toward something more complex.

On Independence Day—May 14, 1948—when I was not yet 10, I remember going to downtown Haifa with friends. None of our parents were with us. We joined the crowd outside the city hall, listening to the broadcast as David Ben-Gurion, in Tel Aviv, proclaimed the State of Israel. Arab armies from neighboring countries would invade the next day. What is remarkable to me, looking back, is that in a period of ongoing hostilities, a bunch of 10-year-olds had the freedom of the streets without supervision.

The Reali School was an elite institution founded before the First World War. I attended the outpost atop Mount Carmel instead of the school near the Technion campus. My parents had apparently had a hard time getting me into the Reali School; they once confided that I had initially been turned down because, they believed, we were Sephardic. I was one of two Sephardic students in the school; this number would swell to three and then four as my siblings Gabriel and Sylvia enrolled. As a young man, I never experienced any kind of singling out, much less outright discrimination, on account of my origins. But my parents clearly had a different experience and were acutely sensitive to the issue.

At school, in my early adolescence—I was perhaps 13 or 14—I was part of a high-spirited group, verging on wild, and a frequent source of trouble. It was around this time that I joined the Scouts, as did virtually everyone else I knew. It was a coed group, one of the major youth movements in Israel. Others included the extreme socialist group Hashomer Hatzair and the moderate socialist group HaNoar HaOved. The Scouts, or Tzofim, embodied socialism’s most liberal wing. Participation in the Scouts, unlike participation in my school, was something I took very seriously, drawn by the camaraderie, the idealism, and the immersion in nature, and it soon became the center of gravity of my life. My parents were supportive. Being in the Scouts meant two meetings a week, one on a weekday and one on a weekend. It meant three- and four-day hikes into the mountains and other parts of the countryside. And it meant going for the entire summer to a kibbutz.

It was a foregone conclusion that when we graduated from school, at age 18, my friends and I would go together into the army—in Israel, military service was mandatory for both men and women—and would register for the Nahal Brigade, with its ties to agriculture and communal living. After the army, it was understood that the group would go on to form its own kibbutz. I had decided, at around age 15, that I was going to study agriculture, and I was already registered to enroll in the Kadoorie Agricultural High School, a boarding school in the shadow of Mount Tabor.

The future would turn out differently for me. Today, as an architect, I do indeed “work the land,” though not in the way I had anticipated. In those early years, I don’t remember thinking consciously of architecture as a subject of specific interest—and yet, looking back, I can see a connection to themes that would become central to my becoming an architect. The Bahá’í Gardens, which almost functioned as my back yard, instilled a deep and enduring love of gardens and landscape. Intuitively, I was aware of the two architectural languages expressed in the middle of Haifa—the Mediterranean vernacular (stone, sensual, warm, domed, rustic) and the modernist International Style (white, minimalist, cool, curvy, formal). I certainly didn’t use words like language or vernacular in an architectural sense, but I registered the aesthetic distinction between downtown Haifa and uptown Haifa, something that ripened in my imagination over time.

In the early 20th century, when the Jewish community in Palestine started building places to live—new towns like Tel Aviv and the new neighborhoods of Haifa—it initially adopted a kind of Romantic Middle Eastern approach, making buildings with arches and domes. The original Technion, built in 1912, is such a place. But then, in the 1930s, a wave of immigrant architects arrived from Europe, fleeing the growing anti-Semitism and the seemingly inevitable drift toward war. They were Bauhaus-trained or German-trained or Vienna-trained, and they built whole communities employing a modernist vocabulary that had not taken root to such an extent anywhere else in the world. The so-called White City in Tel Aviv, for example, today a UNESCO World Heritage site, has some 4,000 Bauhaus-style structures, mostly three- or four-story apartment buildings but also schools, concert halls, theaters, and department stores. In Jerusalem, the British had legislated in 1918 that everything in the city must be built with Jerusalem limestone, a softly golden local material that has been used for building since ancient times; British authorities hoped, by mandating its use, to preserve the city’s harmonious color and texture. And so, in Jerusalem, Bauhaus architecture is clad in Jerusalem stone. I call it Golden Bauhaus.

I can see other aspects of my early interests that are almost premonitions of what would come. Thinking now of the high regard in which I held my father’s Studebaker, I realize that I must even then have had an intuitive feel for design, although the name Raymond Loewy—responsible for the streamlined S1 locomotive and, later, the Shell Oil Company logo and the classic color scheme and typography of Air Force One—meant nothing to me.

The demands of ordinary life in Israel also brought a familiarity with what communities must have to sustain themselves. During the War of Independence and the first years of Israel’s statehood, amid stringent austerity, everything was rationed: two eggs per person a week, very little meat. My family had an easier time than some, because my mother’s brothers, who had moved to Dublin from Manchester, were shipping us boxes of food. But still, with austerity, we were all encouraged to become farmers. We used the ancient terraces around the house to plant vegetables. I had a henhouse in the garden and 25 hens that produced quite a few eggs a day. I had a donkey. I had pigeons.

I also kept bees—I was completely absorbed by the social organization of these insects and also by how they built their structures with such precision. Again, I wasn’t thinking in terms of architecture or about the process of bringing physical structures into existence. I would later learn about geometry and close packing and the platonic solids and other relevant ideas. In the moment, I just enjoyed beekeeping.

In school, my friend Michael Seelig (who also eventually became an architect) and I made an enormous model, which we built using an old door as the foundation. It was about three feet wide and about eight feet long. The surface was made of clay and plaster. We created mountains with waterfalls and painted the scenery to be realistic. Then we added hydroelectric installations and windmills to generate power. It weighed a ton. Our parents had to get a truck to take it to school. But the model was a sensation. To this day, I enjoy immersing myself in the work of the model shop at the office. Fortunately, we use lighter materials than clay and plaster.

Finally, as I think about the early influences on my career, I cannot forget the places where I lived. I was born in a three-story modernist apartment building. Our residence occupied the second floor, and it had a small balcony. When I was 10, we moved up the mountain, toward the crest. We lived on the third and top floors of a hillside apartment building, and one entered the apartment directly by means of a bridge from the garden—indeed, because the building was on a hill, every floor could have its own private entryway. We had a magnificent view of the city, and the entire rooftop was ours to enjoy.

My bar mitzvah took place on that roof in July 1951. This was the time of austerity—tzena, as it’s called in Hebrew—but the austerity was relieved in our household by the arrival of fruit, canned meats, and other delicacies sent from uncles in Ireland. That Ireland in 1951 loomed in my mind as the Land of Plenty gives you some idea of what ordinary life was like in Israel at that time. This hillside apartment expanded my concept of “home,” as did the villa where my aunt Renée Sitton lived with her husband, Joseph. Their home, above us on the summit of Mount Carmel, had a garage on the street and a walled garden with a path winding through it. Gently rising with the slope, the house was one story high, with every room opening onto the garden and views of the sea far below. It was beautifully landscaped. I soon came to think of my aunt’s residence as representing a version of the ideal home.

In the new State of Israel, my family faced some serious challenges. My father in particular felt that Israel’s new Mapai party, socialist and dominated by trade unions, was choking his business—denying him import licenses, showing favor to its own allies, and demanding an equity stake in his enterprises. He had a big inventory of goods, mainly textiles imported before 1948, but new forms of price controls made that inventory unprofitable to sell. Some of his competitors were selling their stock on the black market and making good money, but he would have nothing to do with illegal transactions. He believed he was being treated as a black-marketeer anyway—watched closely and inconvenienced in every possible manner. He took to calling the government “the Bolsheviks.” But there was more to it than that: my father believed that he and other friends were being singled out for harassment because they were Sephardic and because our relative affluence had become a source of envy.

He was also worried that I was being indoctrinated into socialism at the Reali School and in the Scouts. I certainly identified myself as a socialist, and I was committed to the kibbutz movement and to the cooperative movement, reflecting the values of Zionist socialism that were woven through our education. I marveled in those early days of the nascent state that the bus company could be owned and run as a cooperative and that various industries—glass, steel, dairy—were also cooperatives, all owned by the workers themselves. I saw a kibbutz in my future. Once, on parents day, my father made a speech at the school about socialist ideology and why it was inappropriate for an educational institution to press such an agenda. Even before it happened, I am ashamed to say, the event filled me with anticipated embarrassment—not only for the substance of what he would say but also because of his less-than-perfect Hebrew and his Sephardic accent.

Israel’s elections in 1949 and 1951 did not promise relief for an entrepreneur like my father. And so, in early 1953, my parents made their decision: we would be leaving Israel and putting down roots elsewhere. Emigrating from Israel in those days was a big deal. Jews who left were referred to as yordim—dissenters. It was a derogatory term, painful to hear. Emigration was seen by the authorities as a sort of national affront. Tickets for passage by ship or airplane had to be purchased with money sent from abroad. My teachers at the Reali School, learning of our departure, invited my mother and me to school. They acknowledged that I was the class troublemaker but said they would welcome me back if I ever returned. In the end, it seemed, Israel wanted to keep even its misfits.

The news that my family would be leaving Israel was, for me, deeply traumatic. I was firmly planted and happy. I was also living in a spacious home—not everyone in Israel was—and enjoying a comfortable life. Regardless, as a boy of 15, I didn’t have much choice in the matter. Looking back, I can appreciate a reality that I never gave much thought to at the time: how searing the decision must have been for my parents. My father was 45 and my mother 38—they were young people but not “young” when it comes to changing countries. My mother began selling off our possessions. She kept the Bechstein grand piano and some of the furniture, which was put into storage until we knew where we would be living, but she sold the Studebaker. The family business was shut down. Financially, our situation turned out to be more precarious than we might have expected.

There was also the vexing question of where to go. Much of my father’s extended family had left inhospitable situations in Syria and Lebanon and was living temporarily in Milan. Relatives had scouted out various options and had their eye on Brazil. They had gone so far as to send one family member to South America, who returned with a license to build a pulp-and-paper factory. So, Brazil was a possible destination, and many family members pooled their resources and made their way to the Southern Hemisphere. They proliferated and did well, in industry and banking. Today, there is a formidable Safdie clan in São Paulo.

My mother did not warm to this plan or anything like it. She wanted to go only to an English-speaking democracy. And so, our destination became Canada. My father knew a few people in Montreal, including an older brother, who would assist with the visa. His youngest brother, Zaki, would lend him $20,000 to start a new business. Getting entry visas was going to take a while, and we’d also have to get medical tests and clearances, so we joined our relatives in Milan until the paperwork was ready.

In February 1953, we boarded an El Al flight for Rome. It was my first airplane trip. The flight attendants were dressed with what to an Israeli boy seemed like unattainable elegance. I was astonished that food was served. Two years earlier, my father had been on a flight to Paris that had crashed on takeoff. The airplane had departed in the midst of a snowstorm, and the wings had not been properly de-iced. Miraculously, everyone survived. That episode was certainly on my mind as we took off. But once we were up in the air, I adjusted to the experience quickly—as if it were something I’d been doing for years.

At the airport in Rome, I remember going to get a snack and having my first introduction to a drink called Coca-Cola. I can still taste it on my lips. That night I ate pasta and a steak cooked rare. In subsequent days we visited Hadrian’s Villa, the Colosseum, the Pantheon, the Baths of Caracalla. I loved the pines of Rome—the umbrella pines that seemed to define the horizon everywhere one looked—and the Italian landscape more generally. After traveling north, we stayed in Milan for a month. We went on excursions to Lake Como and to Stresa, on Lake Maggiore, where island palazzi rose from the water. One evening, my brother and I climbed up to the roof of Milan’s Duomo. I was captivated by the cathedral’s ornate Gothic wizardry—by its sheer architecture, a concept I may at last have been starting to reckon with. Now I understand my parents’ overall strategy: to soften the blow of leaving our home in Israel, we children were being treated to three months of wonder in Europe.

Growing up in Israel in those early years of nationhood had been an extraordinary experience. But I recognize the insularity of the scene. Until my mid-teens, I hadn’t met many foreigners, hadn’t eaten unfamiliar foods. Our diet had consisted of traditional Aleppo cuisine—stuffed eggplant, roasted chicken, and of course hummus and olives. I knew basically nothing about the world, except the small world I mistook for the universe. This was before television and even before glossy magazines. Then, all of a sudden, I was thrust into a new environment—indeed, into many new environments. Every day brought a fresh discovery. By the time I got to Montreal, after three months in Europe, I was a different person.

We arrived in late March 1953, greeted by the lingering gray of winter, the early darkness. The buildings were a somber brick—not the white plaster and glowing limestone I was used to. There was snow on the ground, melting slowly with the changing of the seasons, and everything left by dogs in the previous three months had combined with the mud and the trash left by human beings to turn the streets and sidewalks into a slippery soup. We checked into the Queens Hotel, on Peel Street, for several days until we could move to an apartment on Sherbrooke Street in Westmount, an Anglophone neighborhood in the bilingual city. In a few months, yes, the trees would be green. There would be warmth in the air and color in the sky. But for the moment, I was in a state of total shock.