Saigon Summer

A spy’s daughter remembers the haunting unreality of embassy life in South Vietnam before the fall

One summer evening in Saigon in 1974, we were invited to dinner at the home of another U.S. embassy employee, probably a covert operative like my father. I don’t remember who he was, but I recall the house—an elegant colonial villa with high ceilings and boldly colored tiled floors, surrounded by a high concrete wall. We parked on the street, walked past two guards, and slipped through a slender door cut into the wall’s façade. Like so many experiences during this sojourn of mine, stepping through that portal felt uncanny and intriguing and off. The country was at war, the enemy digging its steady way down the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Yet here I was, a rising junior in college, tagging along with my parents in hand-tailored dresses to elegant dinner parties featuring French food served by beautiful Vietnamese girls. I was annoyed at my mother that whole summer and jealous of my brother, two years younger, but I remember feeling, as I passed through that almost invisible door in the gate, that I was entering into a private and ephemeral principality, a world that could crumble at any second.

After dinner, my mother pleasantly tipsy, we ventured into the warm tropical night, across the dusky garden with its pots of fragrant plants, and out the magic door. Not a guard was in sight. Residence guards, in their little booths, often fell asleep in the evening, worn out by their bored, day-long vigils in the unrelenting heat. The embassy people joked that they hoped the guards would wake up if the Vietcong arrived. By this time in Saigon, everyone was exhausted. No one knew when the war would end, and people spent the slow-moving time anxiously, waiting for its conclusion.

Overfull, in our party clothes, we eased into our embassy car, and my father pushed the stick into first gear. As we pulled away, he began to laugh and then to roar. Hearing him laugh in this broad, full-throated way was unusual by this time in his life.

“Look at this,” he said, indicating the windshield. We all looked. It was clean and clear—too clear, uncannily clear, and disorienting. Was this clarity real, or were we hallucinating? And then he waved his hand right through the glass. The windshield had been plucked, whole, right from under the guards’ noses.

My father laughed some more. “The guards were probably in cahoots with whoever did it. … I’m sure the men in the motor pool will just go right down to the black market tomorrow morning and buy it back.”

The note of cynicism was new in my father’s voice, and troubling to me, as was so much of what happened that summer when I turned 20.

But I am getting ahead of myself.

A month before, after a long journey from my Minnesota college, via overnight stops in San Francisco and Hong Kong, I had arrived in Saigon to spend the summer break with my parents. As I gazed out the window of a Pan Am jet traversing the world, my thoughts wandered to the one book I’d read about the country: The Quiet American by Graham Greene. In that novel, the jaded cynicism of longtime English war reporter Thomas Fowler is pitted against the naïve idealism of Alden Pyle, an American CIA operative. Toting romantic and high-minded theory but little experience, Pyle seeks to build a democratic, noncolonialist, non-Communist “Third Force.” Fowler, however, doubts that the Vietnamese are driven by ideas like liberty. “They want enough rice. … They don’t want to be shot at. They want one day to be much the same as another. They don’t want our white skins around telling them what they want.” In his estimation, liberals, in order to maintain clean consciences, abandon their allies and leave them to be crucified. When, out of misguided American can-do-ism, Pyle secretly funds a bombing that kills innocent civilians, Fowler, harboring his own set of lies, arranges Pyle’s assassination. I’d gleaned from the book a vague sense of conflicting, mixed, and murky moralities but couldn’t follow the ins and outs. I mostly just took in the noisy jumble of Asian life depicted there.

Landing at Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut fit my preconception of an airport in a country at war. It was chock-a-block with soldiers in dark khaki toting machine guns and crowds of Vietnamese milling about the terminal with overstuffed bags. From them I caught a fleeting whiff of anxiety. These people were fleeing something bad. My chest began to tighten—and then I was whisked away in an embassy car to the American cocoon.

As I stepped into my family’s new home, the pristine elegance of which immediately tantalized my youthful hunger for beauty and soothed my jetlagged limbs, my mother delivered some dismaying news: “The house only has two bedrooms, so we thought, since you’re older, that you might like to stay at the Duc. That’s the embassy hotel. You’ll have your own room and room service. It’ll be fun.”

My mother’s voice was blithe—I didn’t yet register the falseness in her cheer—but I was caught off guard. I looked at her, flanked by my father and my brother. She had her hand on Andrew’s shoulder. My brother would get to stay in the bedroom with the high, arched ceiling and the French doors to a balcony overlooking the garden, and I would stay alone in a hotel? It didn’t seem fun to me at all. It felt like banishment. It felt like my mother was finally getting to have her son and my father all to herself.

My mother hurriedly added, “There’s a pool on the roof at the Duc. You’ll love it.” She was clearly trying to head off my usual flip, “Whatever you want, Mom.” I was practiced at acting like I didn’t care. My mother and I had a contentious relationship rooted in a complex love. But I felt as if I were being extruded, perhaps, I would realize years later, like the jealous United States was, by sleight of hand, extruding its own wayward, threateningly noncompliant offspring. I don’t know if my mother knew what she was up to. People can simultaneously know and not know what they’re doing, can keep their own secrets from themselves. At any rate, I was crushed.

Seeing my room in the nondescript, five-story, concrete-block hotel didn’t raise my spirits. It was an average room reminiscent of many others I’d stayed in on home leaves when my family crisscrossed the country, hurriedly trying to cram in visits to as many relatives as possible during brief landings on American soil. It had two beds, two dressers lined up side by side along one wall, a closet, and a bathroom. It was spotless and military-utilitarian, tan and bland—a place where a spy wanting to keep under the radar would hang out. Which is what it was. The Duc Hotel was not really an “embassy” hotel. It was the Saigon billet for American spies.

The place was eerily quiet. On the ground floor, a receptionist sat at a desk and a couple of military guards loitered. My father, showing his ID, introduced me. We passed one tall, grizzled, disheveled man in the hallway as we made our way to the room. But otherwise: silence. During my stay there, I’d occasionally see a man in rumpled khakis or another in a shirt with epaulettes heading out with a briefcase, or a hairy fellow in shorts making his way up to the rooftop bar, but I never crossed paths with any women or other teenagers. It was a furtive place, a place for the fagged-out and the hiders-out.

When my parents left me there that first night, my mother fluttering on about what a nice room it was, I gritted my teeth and bucked up. Plus, I was too exhausted to protest. I got between those sheets with the military corners, and sank. But in the morning I woke to the colorless, empty walls.

I called my mother, and she cheerily said that the cook had a great breakfast waiting, and that she had some news for me. A car took me to 151 Phan dinh Phung, where a uniformed cook served me mango and toasted French bread and scrambled eggs on fine china. My mother, drinking dark French coffee, sat with me. She was excessively hearty, as if to assuage her guilt, or to butter me up—and then told me she and my father had gotten me a rare summer job at the embassy. I’d be working for the personnel office, rewriting and reassembling the embassy personnel manual. Furthermore, I could do the revising anywhere I wished. “It’ll be fun,” my mother said again. And so my Saigon summer began.

I remained disgruntled and hurt about my digs, but after a day or two, things seemed on track, normal. I was in an unusual spot, but as a “Foreign Service kid,” I was an old hand at this, having already been plunked down in several exotic overseas locales, including other poor, conflict-ridden places. (My father had diplomatic cover for his real job.)

[adblock-right-01]

Saigon had a sort of beaten-up grandeur. The broad, tree-lined avenues provided the city good French bones, and the presidential palace stood regally despite the battered roadblocks and swarms of soldiers. Both the major arteries and the smaller lanes were alive with honking mopeds and milling people. A huge black market of canopied stalls snaked along the central square, where people were selling anything and everything they could dig up: knock-off watches and cameras, fresh baguettes, old clothing, broken appliances, French primers and novels, dog-eared Playboys, GIs’ cast-off T-shirts, cooked rice dishes, U.S. Army paraphernalia, condoms, fish, vegetables, car parts (including windshields), and counterfeit and stolen everything else. Delicate women in creamy yellow and pale pink traditional ao dais shopped with baskets over their arms or roared by on motor scooters. Other women lingered languidly in doorways. Old men squatted at the walls, beating away flies while children raced around frenetically. The young and middle-aged men were all in uniform, as were many of the older ones. They meandered through the market or lounged in groups at the sand-bagged street corners, their guns hung slack over their shoulders or resting against the sacks of sand, idly chatting, waiting for something—I didn’t think much about what. The men seemed drifting and uneasy, and a little fishy, but I was used to that—I had lived in Chiang Kai-Shek’s early Taiwan, another place with restless uniformed men. I passed a lot of maimed people on Saigon’s sidewalks, but I was accustomed to that, too, from a childhood spent in the developing world, where many people seemed to have sores and scars or to be missing a limb.

We occasionally went out to dinner at small French bistros or tasteful, exclusive restaurants serving curries with boiled egg, cashews, dried fruit, diced mango, chutneys. Once my mother took my brother and me for tea at the Caravelle, a quintessential colonial hotel patronized by journalists and diplomats—first French ones, and now American ones, and every other sort of drifter or war follower from around the world. (Nearby was the Continental, where in Greene’s novel, Fowler and Pyle meet to argue the truth about Vietnam.) The building was creamy white, with a grand, columned veranda set with wicker furniture overlooking the bustling central place. High ceiling fans whisked coolness downward as subtle, watchful waiters brought us tea and scones. Who were they spying for, I wondered. The whole thing seemed like pretend: my brother, my mother, and I sitting daintily, drinking tea from clinking china and observing the real world grinding its gears.

Our parents tried to conceal the war from us. My father would say, “Nothing to worry about. The VC aren’t anywhere near Saigon.” We, like everyone else in the city, were in a kind of limbo. Perhaps in a finessed act of deception perfected by foreigners, my parents communicated a calm assurance that we were well sheltered—blotting out the truth the Vietnamese all knew: that we were living in the eye of the storm.

The author’s mother (wearing badge).

Conscientious by nature, I worked intently at my task, but I did take long lunch breaks, either by myself at the Duc’s rooftop café, or when I made one of my deliveries at the embassy. At the embassy pool, I’d find my parents and their friends, order a Coke and burger, arrange my legs on my chaise lounge for maximal tanning, and eavesdrop as the men in their seersucker trunks bantered with my mother and her friends in their batik one-pieces. Other noontimes, I’d go home for lunch, where my mother would greet me with “Oh Sara, come see what Mai Linh has made us” in her ever-solicitous tone. A few years later, I heard the quip, “Feeling guilty means you’re doing what you want,” and I would think of my mother that summer.

Often, when I arrived at home—morning, noon, or night—the living room would be full of American women cradling Vietnamese babies in their arms and bouncing them on their laps, and toddlers blundering around the coffee table. My mother was the embassy’s social service coordinator. One of the embassy wives’ main missions was to provide aid to war orphans and to help grease the skids in the evacuation process—to get the children to the United States, or Canada, or Australia, or Europe, wherever they were headed, as quickly as possible. So my mother and her embassy-wife friends were always visiting orphans, taking them home for the weekend, or looking after them for the last few days before they were sent off in an airplane, to accustom them a little bit to English, or simply to feed them before they departed. I’ve never seen women so delighted. The children were adorable, no matter how handicapped or fussy or skinny, and the embassy wives, who weren’t allowed to work for pay or do much of anything else, reveled in their surrogacy.

I got a kick out of all the babies, like everyone else, and admired my mother’s dedication to them, but at the same time, watching her cuddle and coo made me squirm. I didn’t examine why. It was another of the recognitions I didn’t want to have that last summer of my naïve contentment. My mother felt deeply for those in pain and less so for everyone else. I therefore didn’t merit the full glow of her attention. It was a long time before I understood this.

As for my father, the spy, naturally I had little sense of what he was up to. I’d learned of his true occupation when I was 15. “I don’t really work for the State Department,” he’d said. “I work for——” But I hadn’t the foggiest idea of how he spent his days. Was he paying off armed hooligans in creepy dives on trashy streets? Concealing Vietcong informants in hideaways? He was much quieter, more elegant, and much less brash than Alden Pyle in The Quiet American, my one source of knowledge about spies, aside from I Spy and James Bond. Back in Taiwan, my father had been an eager young man, riding high on post–World War II conviction, but he was never showy. He was the hide-in-plain-sight sort of spy, not the hail-fellow-well-met type from the Ivy League social set. My father’s Mandarin was very good—the CIA had sent him to Yale for a year to perfect it—and I knew he’d spied on the Chinese in Europe as a liaison with Dutch intelligence when I was in middle school and had worked with the overseas Chinese in Borneo when I was in high school. But I’d never really had a sense of what his work looked like.

In Saigon, it was the same, though he did mention that he and some other Americans were running a radio station that beamed American propaganda to the Vietcong, the North Vietnamese, and Laotian and Cambodian communists. One day, he pointed to a big square building and said, “That’s House Seven,” where the radio station was.

The only other whiffs I got of spying and spies came from eavesdropping on my parents and their friends as they chatted and joshed around the embassy pool at the lunch hour and after work, and from meeting my father’s boss. The CIA’s chief of station, Thomas Polgar, was a short, Humpty Dumpty of a man with eyes so sharp and intelligent that they seemed to bore straight into your brain. When my father said, “Tom, I’d like you to meet my daughter, Sara,” those eyes seemed not sinister—though I could imagine them being so—but respectful and curious. I had the sense that Mr. Polgar liked my father, and this made him predisposed to like me. His young wife was on her first overseas tour, and my mother began to look after her, putting her to work with the orphans and helping her to feel a little less green.

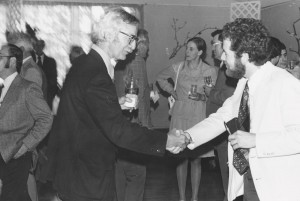

The author’s father (left) at a diplomatic reception.

So it went for a month or so—a quotidian routine of visits to orphanages, overheard poolside banter, and slow but diligent work on the embassy manual at the Duc. But then things took a turn, and the world started to get confusing. My parents began acting strangely, and a sense of unease set in.

The initial glow of my surroundings began to diminish, and I started to see something more about Vietnam. I began to look at the sandbag soldiers’ faces. They looked infinitely weary and their waiting seemed agitated now, their bodies twitching, waiting for the explosion. The beauty of the Vietnamese women seemed forced and desperate, their eyes bruised, their faces drawn, tinged with a grinding anxiety.

Sometimes at the dinner table we could detect the distant rumble of artillery fire. “Hear that?” my mother would say with more forced cheer, as though it were something interesting, and then give an almost imperceptible shudder. My father always followed up with, “Oh, it’s just outgoing mortar rounds. Nothing to worry about. Probably just the soldiers at the post getting bored.”

Then one day, my mother took me to a hospital I’d never visited before. It was jammed with crying and sick people. There weren’t enough beds, so patients were lying on blankets and mats all over the floors—many of them children whose arms and chests had been charred by napalm. Suddenly the war was not just soldiers lounging at their posts at the presidential palace.

Initially, my poolside lunches with my parents and their friends had given me a delicious sense of being grown up. Now, as I sat by the sparkling water in my bikini, I picked up a different note in my father’s voice. This wasn’t the upbeat, jocular political talk, with the tone of wonderment at the shenanigans of the world I’d been used to hearing all my life. This conversation held a sharper criticism, and its mood was darker.

One day I sat up in my lounge chair, forgot about my tan, and deliberately listened. I’m sure the adults didn’t notice. My father’s good friend, whom I will call Alex, said, “Snepp is putting it like it is.” My father said, “Yes. Bully for him.” Frank Snepp was the CIA’s chief North Vietnamese strategy analyst, a handsome, dapper man younger than my father and his friends, the bright boy at the station. And it was clear, as my father and his friend talked, that they thought Snepp had spoken the truth about the war to the ambassador when he’d said that the North Vietnamese were making steady progress in their drive toward Saigon. The ambassador, though, was still putting out foolish statements about winning the war.

“All the sources—everything—points Snepp’s way,” my father said. He and Alex, it was clear, thought that what the White House and the State Department were saying was a lot of hooey. The ambassador believed if you proclaimed something, it was true. I thought of Graham Greene’s observation that “Innocence is a kind of insanity.”

“Yeah,” Alex said, “I hear from our guys that the VC’ll be here about tomorrow.” And my stomach turned.

The men laughed bitterly. My father, who had started out his career as Alden Pyle, was turning into Thomas Fowler.

One evening at a party, my father introduced me to a man he called “my new friend.” When my father introduced me to someone, I always felt like a treasured princess. He’d put his hand lightly on my back and extend his other arm toward the person I was meeting and say, “This is my daughter, Sara,” like those were the most important words in the world. Fathers and daughters are different from mothers and daughters.

The man he was introducing me to wore a well-cut jacket and trim trousers. He was a square-jawed Eastern European whose eyes displayed the same sharp intelligence that I’d seen in Mr. Polgar’s. My father and the man had a sort of mutual knowing between them that was both markedly intimate and a smidgen sinister. I had the feeling this man was doing something for my father—delivering secrets of some sort. This was probably true. The whole encounter awed me, made me sense deception, and also aroused in me a shiver of fear that my father was trailing his fingertips in toxic waters.

[adblock-left-01]

One day in the midst of all this, my mother had to deliver some supplies by plane to an orphanage near Nha Trang, a town within a territory now occupied by the North Vietnamese. The town itself was safe, I was told, though apparently the Vietcong were encroaching all the time. How the embassy defined “safe” I didn’t know, but I trusted its assessment. Our main objective on the visit was to go to the beach—to swim in the South China Sea, which my mother said was “sheer beauty,” and to eat lobster at Jacques’, which my mother called “divine.”

Sure enough, the South China Sea was stunning. My mother hired a fisherman, and he rowed us in his little boat out into the bay. There, we hung over a gleaming, gently undulating, completely transparent emerald infinitude that stretched out to the horizon, and down to perfect, rippled white sand. I couldn’t even tell how deep the water was, it was so clear.

I slipped from the boat into a perfect coolness, and experienced one of those rare moments of sublime transport. I floated, I dived, I breaststroked way out toward the curve of the globe. I lay on my back, held up by the deeps, and felt borne aloft in the safe and welcoming arms of the great mother sea goddess.

Back on shore, my mother, the real one, took me on a stroll through the town of low, one-story houses and barracks set along broad lanes. All this was fine, until she pointed to the rolls of barbed wire that ringed the town. The truth penetrated. We were in a makeshift fortress surrounded by flat farmland. I couldn’t see how that barbed wire and the guards posted to its edges could keep out a determined enemy. “The Vietcong are just a little way off, out there in the woods,” my mother said.

After this sobering tour, it was late afternoon and my mother said it was time to go to Jacques’. A peaceful tread down the pristine sand took us to a wood-slatted hut, with a veranda, perched high on stilts. Up the stairs was an exact replica of a French bistro with four small tables covered in red-checked cloth. A wild-haired, burly Frenchman in an apron and short-shorts appeared and asked us to choose a table. He waved his towel around the room with a sense of proprietary pride, though we were the only diners. I shrank a little under his French hauteur, frayed though it was, like his towel, around the edges.

This Jacques—owner, waiter, and cook—served the freshest and most exquisite meal I have ever eaten. Lobster straight out of the sea, crisp pommes frites, and a tomato salad glistening with drops of oil. My mother and I chewed slowly, savoring every bite, and sipping the red wine he set before us. Out the window, the emerald sea glinted pink and yellow as the sun lowered in the sky. Once in a while we’d hear a boom, and my mother would say, “That’s the VC.” Periodically, Jacques said, Nha Trang had been overrun by the enemy, but so far they had always left him alone. They knew he was a harmless Frenchman, he snickered.

How strange to see this Frenchman, a denizen of the last conquest of Vietnam, subdued but thriving within the hazard. I wondered why our government couldn’t look at Jacques and see its own—best—fate. (He was a warning, like Fowler in the book.)

I flew back to Saigon alone, sitting on a fold-down canvas seat, the only passenger on a C-47, the cargo workhorse of the war. My mother had to go visit another orphanage, but I had to return to work on my manual. On the way, I tried to add up that swim in the emerald sea, the war pushing against the barbed wire, and the meal at Jacques’. The arithmetic eluded me.

By then, my mother had taken me back into the family home—perhaps the guilt finally got to her. She’d found a rice-paper screen at the market and set it between the beds in the second bedroom so that my brother and I each had a section to ourselves. But used to the Duc by now, I sometimes returned there to work on the personnel manual under an umbrella beside the gleaming rooftop pool, often with a spy or two sunbathing or laughing with his mate at another table. In a way, the Duc became my safe house, too.

I left Vietnam at the end of the summer with a pair of beautiful gold-loop earrings and some black-and-red cloth woven by the Montagnard tribes, which were helping the CIA locate the Vietcong as they made their way down the Ho Chi Minh Trail to Saigon. I was tanned and looking forward to my junior year of college, but as I boarded the gangway out on the tarmac, I had a lingering sense of doom, of a world all mixed up: a world where the ostensible wasn’t true. Surfaces and depths, truths and deceits, had flipped and blurred.

The April after I left, one of the orphan flights that my mother and her friends had helped load crashed in a field off Tan Son Nhut, leaving 138 people dead. Later in the month, because of poor planning on the embassy’s part, my father and the House Seven employees were left behind in Vietnam after the last helicopters whirred off the roof of the embassy and had to thumb a ride on a freighter in the Gulf of Thailand. Even the brilliant Frank Snepp had forgotten to count them for the airlift. The South Vietnamese were understandably dismayed at their abandonment by the United States 40 years ago, and in the end, the House Seven group, including my father, departed Vietnam under South—not North—Vietnamese gunfire.