Love, Kurt: The Vonnegut Love Letters, 1941–1945 edited by Edith Vonnegut; Random House, 240 pp., $35

Most men in uniform never see death. But Private First Class Kurt Vonnegut of Indianapolis was captured at the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944 and shipped to Dresden as slave labor. Decades later, he would describe arriving at “the loveliest city that most of the Americans had ever seen. The skyline was intricate and voluptuous and enchanted and absurd … Somebody behind him in the boxcar said, ‘Oz.’ ” His POW group was housed in an underground meat locker and told to memorize its street address: Schlacthof Fünf. Slaughterhouse Five.

One month later, Europe’s architectural jewel box was gone. In February 1945, the war nearly won, 1,249 Allied planes dropped 4,000 tons of high explosives on the city, destroying 100,000 buildings. Civilian casualties were immense, and are still debated: maybe 25,000, maybe 60,000. To be a victim of firebombing is like being dropped into the sun. Some people instantly suffocate. Others fry, bones and all, shrinking into small, dark brown lumps. Children are vaporized, mostly.

At SS gunpoint, Vonnegut dug Dresden’s dead from the rubble, an extreme tutorial in entropy and decay for the Cornell biochemistry major. He was only 22, raised in a prosperous German-speaking family proud of its Old World ties. The funeral pyres of Dresden became the core of his moral vision and the engine of his later literary fame, but the price of witnessing was nearly unbearable, and everyone who tried to love him paid it, too.

Two women kept him sane. His big sister Alice was his muse, a spiritual twin. His future wife, Jane Cox, a friend since kindergarten days, also a would-be writer, became his literary umpire. “One peculiar feature of our relationship is that you are the one person in this world to whom I like to write,” he told her in 1943. “If ever I do write anything of length—good or bad—it will be written with you in mind. … And let’s have seven children xxxxxxx.” Two weeks after V-J Day, they married and raised, yes, seven children, three of their own plus four young nephews, orphaned after their father’s commuter train fell into Newark Bay two days before Alice died of cancer.

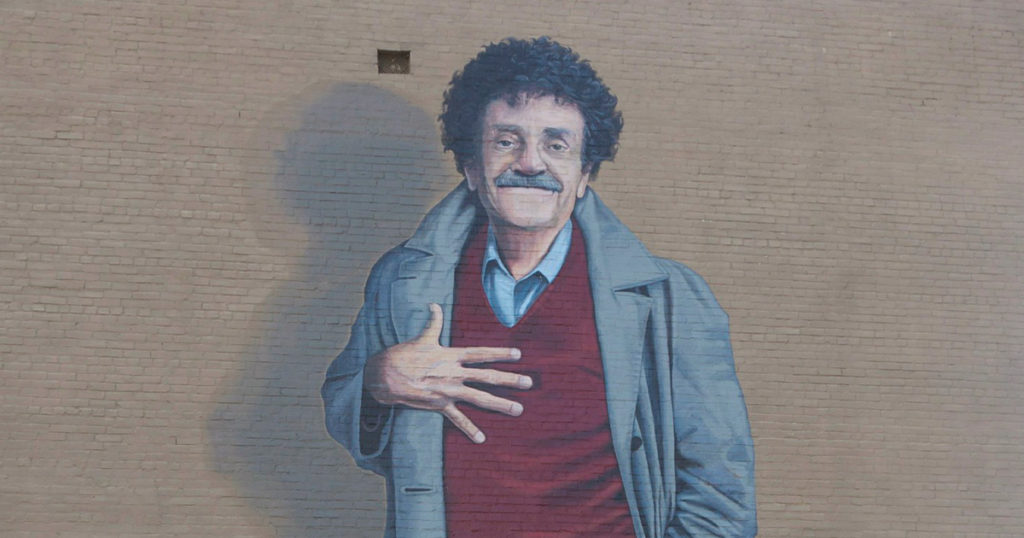

Vonnegut (1922–2007) isn’t taught much anymore, in high school or college; the Norton Anthology of American Literature, 6,448 pages long, includes only the first chapter of his best-known novel, Slaughterhouse-Five. His career is heavily documented: biographies, collections of correspondence, a vast archive at Indiana University. Yet a core mystery endures: how Kurt, the feckless Ivy frat boy, became Vonnegut, satirist to the galaxy.

Two missing links have recently come to light. The first is an 84-page scrapbook of letters and ephemera compiled by Vonnegut and his family, long hidden, sold to a private buyer at Christie’s in 2018. The second is this collection of love letters, recovered by his eldest daughter, Edith Vonnegut, who, while exploring a drift of moldy sleeping bags and old catalogs in her mother’s attic, found “a squashed white gift box sealed with brittle yellowed tape.”

Within were 226 wartime missives, some typed, some handwritten and illustrated. “I found the Lucy of Dad,” she tells us. “The earliest inklings of who he was going to become.” In this handsome compilation, each letter is photographed in full, a perfect choice for penciled scribbles from a fading war.

He took 24 years to express in fiction what he saw in hell, but Jane’s early advice makes clear that Vonnegut, apprentice fictioneer, was a co-production. (Jane’s side of many exchanges has been lost, alas, and her wartime OSS work is little described.) He broods, hesitates, circles. She, the more ambitious, plays therapist and drill sergeant, aware that his colossal neediness responds best to brisk command: read Tolstoy, read Dostoyevsky, get on with your destiny.

“You scare me,” he told her once, “when you say that I am going to create the literature of 1945 onwards and upwards. Angel, will you stick by me if it goes backwards and downwards?”

Love, Kurt is a terrific addition to Vonnegut studies; it is also literary juvenilia. But as Vonnegut knew, World War II was a children’s war, fought by the very young, with noncombatants fair game: “What infants we really were: seventeen, eighteen, nineteen, twenty, twenty-one. We were baby-faced, and as a prisoner of war I don’t think I had to shave very often.”

The Indiana dreamers got no happy ending. Years of poverty capped by head-spinning fame doomed their marriage. Both re-wed, Jane happily, Kurt not. As Korea bled into Vietnam, his gloom and his antiwar convictions both deepened, culminating in the extravagant genre mash-up of Slaughterhouse-Five (1969): the soldier’s tale, the time-travel romp, the literature of witness, the reparative writing for the Dresden dead, each horror and absurdity fueling a cosmic rage that Vonnegut rigidly suppresses, as only a true Midwesterner can.

“One way or another,” he said in 1981, “I got two or three dollars for every person killed. Some business I’m in.”

The Kurt of 1941 would be shocked; the Kurt of 1945, desperate to remember what normal felt like, might only nod. The journey between those dates also maps the gap separating, say, a Private Norman Mailer, clerk-typist, and the homesick slave laborer mining for body parts in the Dresden charnel house. How lucky for literature that Vonnegut had a lifeline when most needed. Love, Kurt, yes, but also Love, Jane.