Not long after my mother died, one of my students gave me an Italian leather notebook with leaves embossed on the cover. It was thick and had a substantial feel to it. Cupping it in my hand, smelling the oaken leather, I wondered, as I opened and closed it for weeks, what I could put in it that would be worthy of it. Finally, I wrote the first sentence, a bold commitment: “I’ll use this book to talk to my mother, to have her help me figure out how to live the rest of my life.”

My father died many years before her, when I was a teenager. But when my mother died, I felt strongly what I have since heard others describe: that recognition—almost a physical awareness more than a thought—that I really am on my own in this world, alone, no one reaching that far back in my life who is also standing out in front.

My mother was sick for a long time. Congestive heart failure and a lot else. Her last year was awful; her doctor said she hung on through sheer determination. Rosie never backed away from anything. During the final week, she went in and out of consciousness, couldn’t talk because of the tubes. But when she was alert, I would talk, and she would nod and even smile when I held her gaze. Finally, the nurses tilted her bed backward to give one final bit of aid to her failed heart. But her systems shut down, and she died swelling with fluid. The nurses removed all the tubes and IVs and disconnected the monitors. They moved her into a resting position and smoothed out the sheets and let me stay with her for hours, the door closed, everything quiet except me talking to her.

The loss of his wife was so painful for my stepfather, Bill, that he couldn’t bear to have any reminders of her around him. She had piles and piles of photograph albums, for she rarely missed a chance to grab onto a memory. (During my cousin Bobby’s wedding she, honest to God, walked up on the altar close to the priest to get a better shot.) If I didn’t take the albums, Bill was going to throw them away. The same with three or four scuffed boxes filled with her memorabilia, some going back to her 20s: my baby clothes folded in with jewelry, old wallets, snapshots, and most valuably her diaries.

The second entry in my notebook comes a month after the first and is telling: “I thought I’d be able to sit with this book and write to Mom, or take it to the gravesite maybe, leaning my head against the crypt—an awful word.” As it turned out, it was a whole lot harder than I thought to write as though I were talking to my mother. The sentences I formed in my head felt artificial, forced, as though whatever I wrote had to be weighty. If nothing else, it was awkward trying to keep the notebook open, standing in front of her grave, attempting to write something … lofty. Talking with Rosie could be funny (my cousins loved being around her), exasperating, heartrending, and you’d be taken with her wily gumption. But lofty? She’d think you were a bullshitter.

For much of my adult life, I’ve been interested in my family’s past, maybe because we knew so little about my father, whose life before he met my mother is obscure. And maybe it’s because I grew up hearing stories about the grinding poverty of the life my mother’s family had lived during the Great Depression in the industrial city of Altoona, Pennsylvania, giving up bedrooms to take in boarders, working dangerous jobs in the railroad yards. I never knew my grandfather Tony; he exists in a few creased photographs and in fragments of stories about losing his leg in a railroad accident. I was able to imagine him in first-person accounts I read of life in the railroad yards and to locate him in tables of labor statistics about the wave of immigration that he and tens of thousands of his southern Italian countrymen formed. We all try to piece our lives together, to create a story that makes sense to us and anchors us. Perhaps my mother’s diaries would help me further develop that story and learn from it.

In those boxes my stepfather gave me, I found four of my mother’s diaries, small books with black cardboard covers pressed to look like leather. The inside covers offer brief epigrammatic advice to the diarist: “Memory is elusive—capture it” and “You will turn aside the veil of forgetfulness.” The diaries would take me closer to the city where my parents started their lives together, beginning about six months before my birth in Altoona and extending sporadically until my parents left in bankruptcy, my father in poor health. With my mother’s writing in hand, I could return to Altoona early in the morning, or in the middle of the night, waking from a dream.

It’s an odd thing to be so loved by someone you know so little about. I hoped my mother’s diaries would reveal more about Tommy Rose, but he is elusive there as well. The little I do know about my father’s history is merely bits of a life told by my mother or one of her brothers.

Tommy was born in Naples in the 1890s. He went to one year of primary school, and in his second year he threw the stool on which he had been sitting at his teacher—thus ending with emphasis his formal education. Later, he came to America with his older brother, Michael. The two brothers settled in New Haven, which, after Ellis Island, was a major port of entry for southern European immigrants.

The one other thing I knew about my father’s past was that before Altoona he lived in Chicago and “knew Al Capone,” who, I came to understand partly from movies, was a big-time gangster. The other name I heard was Lucky Luciano, another mafia kingpin, and my mother noted that my father and Lucky Luciano (she always said the full name) were friends. God knows what my father’s connection was to the mob. Was it gambling or bootlegging? Was he a “businessman” or in the more violent side of the life? What became clear to me is that he came to Pennsylvania to start over—Altoona, a much smaller town than Chicago, far enough away—not cutting ties, maybe, but looking for a new path in the world. My mother would play a major part in Tommy’s transformation.

My mother’s parents, like Tommy, came from southern Italy, but from Calabria, the southernmost tip, the “toe” of the peninsula. What I know of that life comes from my Uncle Frank, the oldest boy. Before his arranged marriage with my grandmother, Frances Pata, my grandfather, Anthony Meraglio, tried to escape Calabria’s bitter poverty by responding to the promises of Italian steamship companies and American heavy industries and migrating to the United States, eventually finding employment in the booming railyards of Altoona. He went back to Calabria, married the 14-year-old Frances, and traveled back and forth, fathering a child upon every return to Italy, my mother being the youngest of four. Finally in 1920, Anthony had accumulated enough money to send for Frances and the children.

Life in Altoona was better than life in Calabria, but it held its own hardship and tragedy. The Meraglios rented a dilapidated house in the company projects across from the railyard. The six of them slept huddled together in the living room and rented out the upstairs bedrooms to boarders, two to a room. The boarders were all men whose wives were still in Italy and who, for a few dollars a week, got home cooking, clean laundry, and a place to sleep. The extra money enabled Tony and Frances to add meat to their diet and to buy shoes for their children. The warm Pennsylvania summers and the freezing winters set the rhythmic backdrop for the deliverance of five more children, two of whom were stillborn. Two of the three survivors—Sammy and Russ—were sickly and needed attention; the third, Joe, was rambunctious and always in some kind of petty trouble. Rosie’s mother made her quit school in the seventh grade to care for them.

As soon as they could, each of the children assumed a place in the household economy, from washing bedclothes to selling newspapers. The Meraglios were finding a tenuous stability. Then one day, in the midst of the smoke and noise of the main yard, Tony was unhitching the ash pan from a locomotive. He slipped the two hoisting chains under the bed and signaled up to the crane operator. As the crane yanked the pan into the air, it slipped loose and caught the startled Tony across his left leg, severing it above the knee. Tony could not work for the next two years, so Frances kept food on the table by making beer and wine and dealing in bootlegged whiskey from the hills outside Altoona. Frank remembers his mother buying off the local cops with shots in the coffee they would drink at her kitchen table. She also tended chickens and rabbits and a small garden, canned vegetables, scrubbed and ironed clothes for boarders and offspring, looked after sick children, and cooked for a household of 15. Rosie would absorb her mother’s endurance as well as a sense that life is a struggle with danger at every turn.

I am holding a faded photograph of my mother. She looks to be about 13 or 14 and is sitting on a wood wagon. Her hair is cut in a crude pageboy, her skin is dusky, and her features are plain, except for her eyes, which are big and sad. She is wearing a simple print dress, the top held tight with a safety pin, high-top shoes, and leggings that have a hole in one knee. Her hands are resting just above her knees, and she is smiling into the camera. Because she raised the second crop of Meraglio children, she felt especially protective of them, worrying constantly about the health of the frail duo, Sammy and Russ, and the doings of her wild brother Joe. She also worried, I’m sure, about herself, fretting with desires captured from the movie posters that caught her fancy. Innumerable times she threw herself between her mother and Joe as Joe got yet another beating for losing precious pennies in a back-alley craps game. Joe would seize the moment and sprint to safety, leaving Rosie to catch the strokes of her mother’s ire. By the time she reached her late teens, she desperately wanted out.

Once the boys grew into adolescence, Rosie got a job in a garment factory across town. The huge brick building was dark and hot, the air terrible, the work tedious, the wages low. During the years of her employment, the Pennsylvania winters were particularly bitter; Rosie had to walk two miles in thin clothing through snowy winds. One morning, she stopped in Tom and Joe’s diner to warm up with a cup of tea. Before long, an older man, impeccably dressed, got up from a far booth, walked slowly over to her stool, and reached for her check.

On one of my visits to Altoona, much later and after my mother told me about meeting my father, I went to Tom and Joe’s for lunch. It was a long, narrow place with a counter and booths. As with so much in the central sections of cities like Altoona, time and economic change had taken their toll. Everything was worn thin, from the name of the manufacturer on the napkin holders to the threadbare cloth towel in the bathroom dispenser. It was midafternoon, and the diner was empty but for an old man at the counter and a couple in the booth behind me talking about somebody who just got out of jail. I sat there looking at the counter where my father approached my mother so long ago. I imagined Rosie cradling a cup of hot tea, raising it to her lips, beatings and sewing machines and movie-inspired dreams running through her head. Then there is this man, dressed like the actor Charles Boyer, leaning gently into her line of sight.

“Can I pick up your check?” he might have said. “Can I sit down?” My mother told me she was stunned, self-conscious. “Well, I, uh, don’t know.” She barely takes her eyes off her tea. Then Tommy asks her if she wants something to eat. She is starving—she remembered that 50 years later—but says nothing. Tommy orders scrambled eggs and bacon and toast. Warm food.

Rosie gradually begins talking a little, then a little more, the food and the out-of-the-blue attention turning her gaze up from the tea, from the plate to my father. We can only guess what web of hopes and desires held them in those few minutes, but for Tommy there was the promise of a young Italian woman, free of his past, the possibility of a family. For Rosie there was the possibility of a way out of a brutal life. For each a kind of deliverance.

Tommy courted Rosie in proper fashion. He visited her at home and always brought gifts. The first time, a baby lamb for Rosie’s mother, whiskey for her father. It was during this period when Rosie’s brothers, my uncles, first got to know Tommy, and years later they would be able to pass on to me a few early stories. It seems that before the courtship, Tommy was selling building materials in the small towns in the mountains surrounding Altoona. By the time he sat down alongside my mother in Tom and Joe’s, he was running a “suit club” out of a hotel down the street from the house he would eventually buy for us. Whether it was siding or suits, my father had people buy on credit, and he had a crew of locals—in the small towns, in the railroad yards—who would collect a dollar a week, keeping a percentage for themselves. According to my Uncle Frank, Tommy “made a lot of money.” He always had a deal in the works.

Tommy went with Rosie for five years and at some point hired her to keep the books for his suit club. He bought her beautiful clothes, gave her money to have her hair styled, her makeup done. She became elegant. On March 12, 1942, they were married.

It would be hard to overstate the aura of salvation all this had for Rosie. Although I never heard her say a bad word about her mother, Rosie’s adolescent and young-adult life before meeting Tommy must have been hell. Who knows what assaults—along with the domestic labor—that house full of boarders brought. Then came the factory. Later in her life, my mother told me something else. Her mother had arranged a marriage for her to one of the neighboring Italian men, and all my mother would say about it was that it was awful, and she soon left, returning home. The rupture of the local social fabric and the dishonor brought to the family led to beatings, physical and psychological, that my mother only alluded to. (I would read in one of her diaries that the failed marriage much later brought her anguish when the parish priest in Altoona refused to baptize me because of Rosie’s violation of church law.) Imagine, then, Tommy Rose asking for my mother’s hand. It was for her a lucent pathway out of a smothering, vicious life.

In 1943, about a year and a half after they were married, Tommy opened a restaurant in the bustling center of Altoona and made Rosie the owner. Menus tucked in with the diaries note that the Rose Spaghetti House served hamburgers, veal chops, and liver and onions, and a piece of pie for 15 cents, but its main fare was Italian food. I think about what the restaurant must have meant to my mother. Rosie now presided over rows of booths and tables, hired waitresses and cooks, became known to whoever walked in the door. A neon rose glimmered in the front window. An ad in the phonebook listed “Mrs. Thomas Rose, proprietor.”

The photographs of Tommy and Rosie in the scuffed boxes are striking. My father wears tailored suits, sharp crease in the trousers, two-toned shoes, hanky perfect in coat pocket, fedora with a slight tip forward. My mother is in beautiful ’40s dresses, padded shoulders, thin at the waist, stylish hats. They look straight into the camera, Tommy with a calm, confident grin, punctuated in some shots by a cigarette, Rosie with a full smile not seen in any of the monochromatic snapshots of her childhood and adolescence.

The diaries begin here and fill in the story that accompanies these photographs. The entries are written in my mother’s clear Palmer Method script—something that the nuns passed on to her before she had to drop out of school. She was pregnant with me during the early months of the restaurant, so my infancy and childhood become part of the restaurant’s story as well. In addition to her diaries, she also kept a diary for me before I could talk, writing in a child’s voice she imagined for me, each day recording my moods and discoveries and my thoughts about my parents and our future. I’m taken with the idea of Rosie projecting her hopes onto me and conjuring my inner life.

From my birth through the beginning of primary school, my life was defined by the restaurant. In one photograph, I’m standing between Tommy and Rosie—probably on a stool—at the cashier’s station. In another I’m sitting with the cooks at the preparation table; they’re stern, I’m smiling. I remember the blast of heat when opening the kitchen door, the hidden noise and activity, chickens sticking out of large boiling pots. I remember being on the main floor among the customers. I’m leaning on the rough stone ledge of the second-floor window—huge to me at the time—announcing to the world, but really to those seated nearby, that I had just started first grade. To this day, I love being in restaurants right before opening, the prep work and anticipation, or later when the evening is winding down, the busboys and cooks, aprons off, having a smoke, the waitresses cashing out, counting their tips, telling stories about the night. This was the layout of my early life, and the diaries pull the curtain back on it.

The first entry in Rosie’s diary was written on New Year’s Day, 1944: “On Sept. 1, 1943, I opened up a restaurant called the Rose Spaghetti House. I did not think there would be very much work in it, but I got fooled, really I did, for I really am working very hard. But I love it.”

There is one more entry for 1944, in May, when she has come home from the hospital with her new baby. She picks up again in mid-1945 and writes an entry every day through January of 1947. From there—as Altoona’s economy worsens—until the end of 1951, there are only a dozen or so entries, each filled with worry. The restaurant would close in bankruptcy, but Rosie doesn’t mention that. Perhaps it was too painful to write.

As most diarists do, my mother records the events of the day. My first haircut. Watching her kid brother Russ jitterbug at the Jaffa Mosque. A fire levels a nearby building. There is gossip about a guy getting a waitress pregnant. World War II is present through Rosie’s brother Joe in the midst of heavy action in the South Pacific. She celebrates on V-J Day and takes me to a parade, only to wait anxiously through the following months of Joe’s demobilization. She talks to a soldier who wants to kill himself. She hopes Joe “will be the same as he used to be, won’t be disgusted with life.” The other thing of national consequence that appears in the diaries, evident through its effects on the restaurant, is the gradual demise of the Pennsylvania Railroad. “The shops have closed down again for the third time.”

But, overall, it is the Rose Spaghetti House that dominates. The diaries are filled with the details of restaurant life: how good or bad a day it was, a surprise rush of customers, or heavy rain or snow keeping everyone indoors. There are lots of names of cooks and waitresses; some names (Peanuts, Honey) I remember, and they are coupled with praise or damnation. Not a week passes without people showing up late for work or not showing up at all. There is tension, firing, then rehiring. Rosie is constantly filling in—waiting tables, cooking, washing dishes—or trying to cool down the squabbles between cooks and waitresses. She writes that one of them is “a regular pain in the ass,” another is a “skunk.” But when business is good, even if the staff is overwhelmed, the diaries brighten.

Tommy is mentioned often, though we don’t hear or picture him. He paid the bills, dealt with the vendors and the landlord, made the big decisions about upgrading or remodeling. And he typically took the cash. Rosie calls him “the brain man.” She was more in the thick of things, working alongside the cooks and waitresses, managing the flow of customers, even breaking up a fight when a friend of hers pulled a knife on some rowdy teenagers. I wonder when and where my mother wrote these entries. They have the feel of the restaurant to them, a tiny respite from work, dishes piled on a tray. I picture her sliding into a booth between lunch and dinner, writing for a few minutes before someone calls her name. The diaries record the experience of managing a small business, and doing so as the economy shifts, a calamity for so many Rust Belt cities. Against that backdrop, the diaries reveal a young woman thrust into a new life, running a restaurant, being a mother in unusual circumstances, trying to find her way in postwar Altoona.

Good times at Rosie’s restaurant before the city of Altoona starts to go downhill and the spaghetti house goes with it (All photos courtesy of the Mike Rose Living Archive)

Thinking about my mother as this young woman with so much on her mind, I can’t help but wonder about her relationship with my father. As I was at home with various babysitters or down in the restaurant itself, what was going on between them? Restaurants are social places, so even as Tommy and Rosie were consumed with the operation of the Rose Spaghetti House, I know there were people visiting, coming in for a meal to spend a little time with them. There were regulars like our physician Dr. Denny, but, too, there were Rosie’s brothers, or Tommy’s friends from the old days passing through town. Guys with names like Sammy Fashion. In one of my favorite pictures of the restaurant, nine people are sitting along one side of a banquet table. It’s the end of a meal, lots of glasses and condiments and coffee cups and pieces of pie. Everyone’s smiling and looking into the camera but caught with a fork in their pie or a raised cup of coffee. Tommy and Rosie sit in the middle, Tommy with his lips pursed, a sweet look, about to say something. Rosie is smiling fully, legs crossed, hands folded over knee, red nail polish. Rosie’s older sister Jenny in her waitress uniform sits to their left, a bright, round face. At the other end are the aerialists Betty and Benny Fox—when Altoona was booming, entertainers en route to Pittsburgh regularly stopped there. (You can still find vintage postcards with Betty skipping rope on a tiny platform jutting off the ledge of a skyscraper.) The camera flashes, and Tommy finishes his sentence—was he talking with a lean of the head to Rosie? Benny’s cup clicks back into its saucer. Jenny says something devilish—my mother’s favorite word for her—and gets up to go back to work.

Tommy was always bringing gifts to Rosie: a box of chocolates on Valentine’s Day, a dozen roses on her birthday, an expensive fountain pen … and the entries in the diary change for a while to blue ink. “I couldn’t have gotten a better husband,” she writes. “He’s the most wonderful man in this whole world.” The sense of salvation that originated in Tom and Joe’s diner hangs over these entries. “I would be lost without Tommy.” But I don’t know what Tommy is feeling. He enters the diary carrying the roses. I imagine him walking in the front door with that rare full smile of his, grand, generous. But Rosie never quotes him; I can’t hear him. Rosie finds a vase for the roses; the waitresses make a fuss. And Tommy recedes. I study two snapshots from the restaurant floor, Tommy and Rosie with others, including brother Joe in civilian clothes. Rosie is fully in camera, radiant. In one, she cups Tommy’s hand, and he is looking off, as if lost in thought. In the other, he is regarding her from across the table, an inscrutable look, taking in her beauty or assessing it.

Tommy and Rosie occasionally went to the movies together—an Abbott and Costello comedy, the war movie A Walk in the Sun—for the Mishler Theatre was a short walk away. But, Rosie writes, Tommy didn’t like movies much, so she usually went alone, and he would go up the street to the American Legion to play cards. Rosie confesses that she is “movie crazy,” and during the slow afternoons in the restaurant she would slip off to romances and melodramas—with a fair number of tales of deception, seduction, or betrayal: The Postman Always Rings Twice, Scarlet Street, Mildred Pierce. These movies stir Rosie, often to the point of tears. They call up, I would guess, her own swirl of feeling about the tenuousness of things, about loss, and for 90 minutes she can hold her own worries at bay and escape into the troubled lives of others.

The experience is purgative, and she writes again and again that it’s relaxing. She comes out refreshed and goes back to the Rose Spaghetti House. Playing cards provided Tommy with a different release. For a few hours, he could get lost in the play of spades and diamonds, in the small talk exhaled with cigarette smoke around the table. I wish I could sit by him, have him whisper to me what he’s thinking, the probabilities going through his mind, how he is reading the other players. My father as strategist.

The one thing that Tommy and Rosie frequently do together outside the restaurant is to take walks through town. It’s mentioned fairly often and with a gentle note, maybe because it marks the end of a long day. I picture them walking slowly—for Tommy was already having pains in his legs—maybe arm-in-arm, Tommy with a cigarette, Rosie with her purse cradled in her other arm. They probably talk about the restaurant, about me. But what else? They bump into people they know, customers, other merchants, Rosie’s acquaintances from Little Italy. They talk about business, or families, or boys away at war. Rosie kept a scrapbook of newspaper clippings of Altoona men injured or killed overseas, and surely people asked about her brother Joe in the Navy. Chances are, I would be awake when they got home, regardless of the hour. Exhausted, they would play with me—Rosie records my imagined thoughts about this—and when I was older, my mother would make us toast and tea and read to me.

The diaries reveal a fragmented family life. Rosie continually laments not seeing me, and though she is with Tommy throughout the day, it’s rare that the three of us are together at home for any stretch of time. A description of Christmas 1945, written from the restaurant on December 26, is unique among the entries: “I had a wonderful time yesterday because for the first time Tommy, the baby, and I was at home together. We had our first Christmas dinner at home.”

I sit with my mother’s diaries and try to imagine the day-to-day of the restaurant that, for me, exists in isolated though crisp memories. I had no idea that the restaurant for so long demanded so much of my parents. I knew from a young age that we moved to Los Angeles because the restaurant closed, and I heard the word bankruptcy, which I certainly could tell wasn’t good. But for much of my life I had the sense that the Rose Spaghetti House once thrived—look at those pictures of Tommy and Rosie, all style and confidence. The restaurant is anchored in my early experience of Altoona, which, though distant, seems as solid as the brick and steel that I can still see when I close my eyes.

In fact, the diaries reveal that my parents had to relocate the restaurant twice to stay afloat. They lost their lease on the first place and moved to the second floor over Fields Hat Store on 11th Avenue. Then, in desperation, to the ground floor of our house, a few blocks farther north of the railroad yards and away from the business district. My memories, then, are an amalgam of all three places, and with a little effort I can locate some in one place—that second-floor window—and some in another. I also realize now that I do not have a single memory of a crowded restaurant. It could well be that my parents kept me home during the busy times. But still, as I lose myself in the photographs and words and memories of that time, it is empty space amid the chrome and leather that I remember, a few people here and there to talk to, like Dr. Denny or Aunt Jenny, or my mother and father, my father sitting behind the cashier’s station in coat and tie.

I have been trying to understand what motivated my mother to keep these diaries during such a busy time in her life. She never kept one again, to my knowledge, and though she was a consistent writer of letters, she didn’t write much else. One of her friends tells her that it’s crazy to keep a diary. Why did she do it? Was it something a lot of women her age were doing? Did she get the idea from a movie? Did Dr. Denny recommend keeping a diary as a release for the distraught young proprietor? The diaries record hirings and firings, how good or bad a day it was, a few firsts, a few visits, and those listings of many movies. But as the days progress, the entries become a record of anxiety: worries about the business failing, about the mysterious pains in Tommy’s legs, about Rosie’s own health holding up. And woven through the worry are self-recriminations about not being able to spend more time with me. I sit with my mother’s raw anxiety. It is uncomfortable to read.

Then desire breaks through. Rosie wishes she and Tommy could take a vacation to New York. She dreams of visiting places with me when I’m older. She hopes that her work will make my future secure. Tommy tries another remodel. He wonders about moving the restaurant to Pittsburgh. For a few pages, an unnamed “big deal” becomes possible—from Tommy’s Chicago friends?—but that deal quickly fades.

As I’m writing this, I realize the terrible dilemma that Rosie found herself in, as the months with faltering business and longer hours went on and on. This bright symbol of her salvation transformed into a prison house of labor and worry. One 17- or 18-hour day follows another. Both she and Tommy are losing weight. The restaurant was Tommy’s gift, and Tommy was webbed into the core of it. “We used to have a lot of fun with Tommy,” she writes, “but business is getting him down.”

The best answer I can come up with, finally, is that my mother kept writing because she had nowhere else to turn, felt alone even when surrounded by others. “I can’t say anything because after all, it’s my restaurant. What else can I do?” She knows that Tommy is consumed with worry; she can’t keep complaining to him. There are entries where she’s alone in the kitchen at night. Entries when she gets home, and my father and I are already asleep. “I hardly see Michael anymore.” She keeps her game face on, holding the pain close to herself, spilling it out across the pages of her diaries. “Oh God, I don’t know what’s going to happen to us all.”

Toward the end, the entries are sporadic, and the detail thins out. “We can hardly make expenses.” “We can hardly pay anybody.” The final entry breaks my heart. The Rose Spaghetti House has closed. Rosie stops into Fields Hat Store, the shop beneath her second restaurant, to visit a friend. As she’s leaving, her memories of the restaurant flood in on her. To take her mind off things, she goes to see A Place in the Sun, the story of a young man who reaches way beyond his social class with disastrous consequences, and she breaks down, crying throughout the movie and out onto the empty streets of Altoona as the shops are closing.

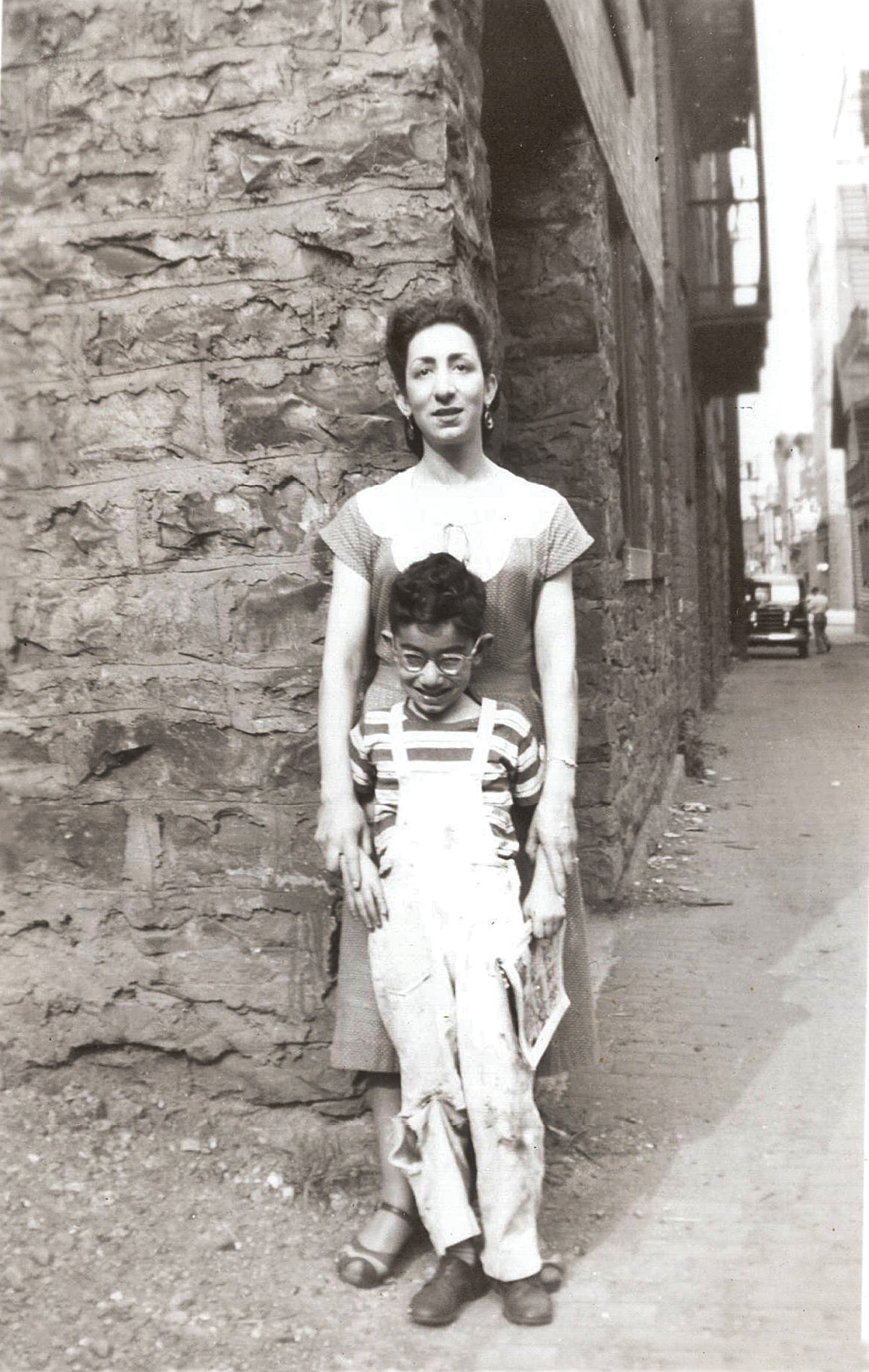

Mike and Rosie behind one site of the Rose Spaghetti House, a week before the move to L.A. (All photos courtesy of the Mike Rose Living Archive)

Soon after the steam tables and booths and chairs from the restaurant were sold, Tommy traveled by train to California to begin scouting out a new life for us. A warm climate would help him, Dr. Denny said, and Los Angeles was a city of opportunity. He would start over once again.

My mother and I stayed in Altoona so that I could finish the second grade. We would wait there until Tommy established himself. Early in her diary, Rosie noted happily that Tommy had started a savings account for me, a college fund. But he had to cash it out. We lived off that money along with steam table dollars, enough to get Tommy to L.A. and me and my mother through the summer until we, too, would board a train west.

My mother rented a furnished apartment in downtown Altoona that, in recollection, has the hue and feel of an old sepia print: beige wallpaper, light cast by a shaded lamp, curtains. I remember sitting on the bed with her, playing dominoes. It was during this time that we went to see Singin’ in the Rain. In her diaries, Rosie had wished I was old enough to go to the movies with her, and this might have been my first one. It filled me with joy. Walking back to the apartment, I danced around the streets the way Gene Kelly did. Watching the movie now, I notice at the end: “Made in Hollywood, USA.” Did Rosie see that? Did it telegraph her impending journey? She must have been devastated, both humiliated and worried. But I wonder if, in some way, she was also relieved, away from the grueling demands of the restaurant, finally able to be with me, maybe even hopeful about the future. What memories I have of that time have a certain calm to them.

I’ve recently talked with two people who were regular customers at the Rose Spaghetti House. One woman contacted me when she read my mother’s obituary, which I had reprinted in the Altoona newspaper. She sent a handwritten note to the funeral home, and I called her as soon as I got it. She remembered me in a stroller and remembered that all the waitresses would hold me. She said she could still picture the first restaurant, the layout of the tables, booths along one wall, a second section three or four steps up—an area for banquets. She remembered Rosie joking with her about her boyfriend away at war—gentle, lighthearted, reassuring her that everything would be alright.

My mother’s diaries reveal the backstage story, off the restaurant floor. But I’m comforted to think about my mother and father as this woman describes them. The Tommy and Rosie of the photographs. Tommy and Rosie as restaurateurs, as the people who have to keep up appearances, create a place that invites you in and lifts your spirits, if only for an hour or two. Maybe in the moment it did the same for the two of them.

When I stood at my mother’s grave trying to write to her, I was desperate to hold on to her and all the life she carried. Her diaries opened up for me a part of her life I would have never known, her inner life right before and after I was born. Amid the convivial artifice of the restaurant, Rosie fashioned a social self, to use a favorite phrase of hers, “among the public.” She wrote about it all, ventriloquizing a voice for me in one diary, and recording her own transformation in another as Altoona’s defining industry collapsed. It is through the telling of her stories that I’m finding a way to live the rest of my life—stories of work and opportunity and the barriers to it, of finding meaning in the hand we’re dealt, of her dreams for me, of desire that propels us forward or flattens us with a broken heart. My story was created within Rosie’s story, and the balance of my story is my striving to fully become Rosie’s son.