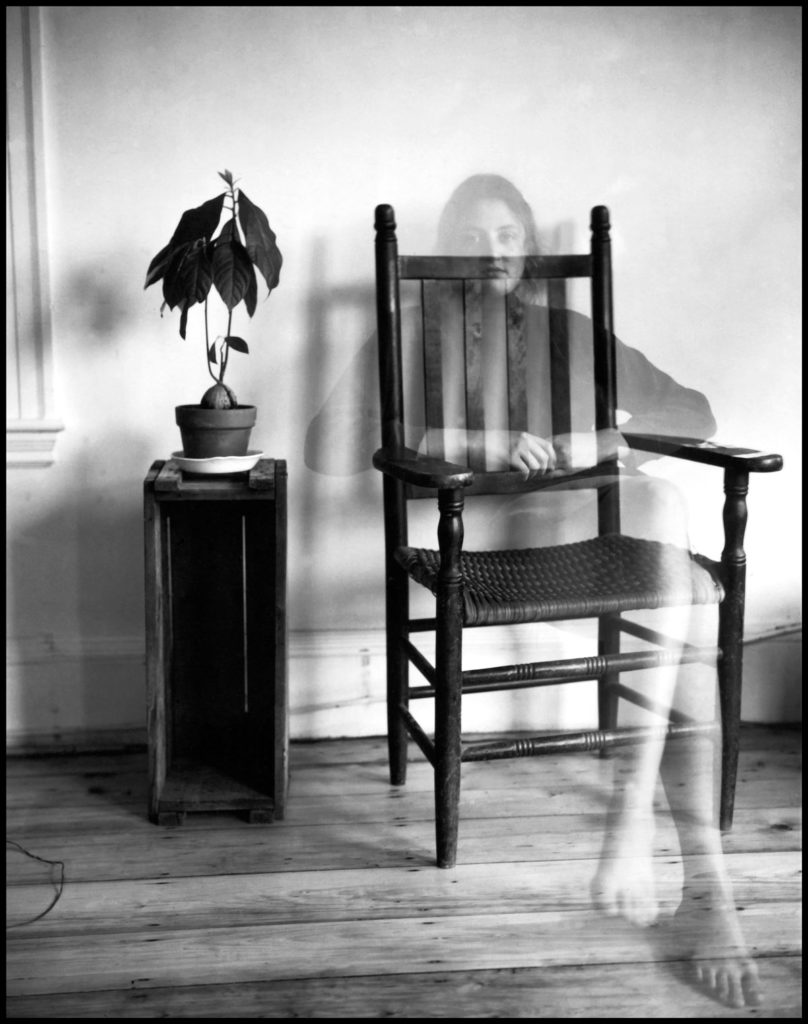

At first glance, you barely notice her. The black-and-white photograph seems to center on a wooden chair and a crate to the left holding up a houseplant. However, a closer look brings into focus the apparition of a young woman. Seated in the chair, she holds her hands in her lap, her legs are crossed, and she rests one bare foot on the floor while the other floats in mid-air beside it. She’s there and not there, visible and invisible. The intensity of her gaze, however, and the effort she has gone through to create the picture—the lighting, the timing, the cable release unfurled on the floor between her and the camera—is unmistakable.

Taken by Susan Meiselas, the veteran Magnum photographer, during her first photography course in 1971, this self-portrait introduces an approach to the medium based on the simultaneous presence and absence of the photographer that has distinguished her art for 50 years. For her final course project, Meiselas photographed herself and each of her neighbors in a shared boarding house, gave everyone a print, and asked them to write about how they saw themselves in her pictures. As her self-portrait suggests, the success of the project, and her work more broadly, relies on Meiselas using the camera to fade from view while she brings the community around her into focus on their own terms. From her earliest work in the 1970s to her most recent book, Tar Beach, published in the throes of the pandemic, Meiselas’s commitment to the social dimension of photography, in which her role is but part of the picture, highlights the value of vernacular practices with the medium and their significance to its history.

The term vernacular photography refers to the countless kinds of ordinary photographs that have circulated in society from the medium’s inception in 1839 until now. The sheer variety of photographic traditions that have emerged during this period has prompted at least one scholar to use the plural, vernacular photographies, to refer to these practices, underscoring the heterogeneity of the genre. Daguerreotype portraits of families in Monrovia, hand-tinted ambrotypes of American Civil War soldiers, picture postcards of Belgian city squares, or, more recently, yearbook photographs, snapshots, portraits encased in lockets, stashed in wallets, or tucked into the rearview mirror of a car: vernacular photographs comprise the gamut of images that, as art historian Geoffrey Batchen writes, “preoccupy the home and the heart but rarely the museum or the academy.”

While characterized by their diversity, vernacular photographs nonetheless share certain qualities, which reveal the limited scope of traditional histories of photography that tend to emphasize artistic achievements with the medium, technological innovations, or the accomplishments of renowned individuals. For one, vernacular photographs frequently appear in groups, such as portraits of family members clustered on a wall, gathered on a shelf, or assembled in a photographic album. Such arrangements suggest that the proximity of photographs or of those in them offers a way to represent the ties that bind the people pictured. In addition, vernacular photographs also often incorporate handcrafted additions, such as painting, collaged elements, or written annotations. Layered onto the photographic surface, these marks call attention to the photograph as “a record of a relationship,” to use Meiselas’s phrase, an image that provides a conduit for the memories and emotions that exist between subject and viewer. Further, vernacular photographs tend to emphasize the physical properties of the photographic print, reminding us that the photograph is also an object to be held, touched, and displayed. Although they occur in many different cultures across the globe, vernacular photographs share a tendency to be placed in domestic or public spheres where families, friends, and communities gather for everyday occasions or periodic rituals that fall outside the realms of official culture.

The qualities that distinguish vernacular photography also characterize Meiselas’s approach to the medium. For example, Meiselas’s projects highlight photography’s currency—and history—in long neglected regional, local, and indigenous communities around the world. Just as vernacular photographs have traditionally been considered too commonplace to be of interest to scholars or museums, the communities at the heart of Meiselas’s photography are typically viewed as too ordinary or, more often, too marginalized to make it into the history books. Her projects that demonstrate characteristics of ordinary photographs, such as assemblage, layering, or tactility, or that incorporate vernacular photographs she encounters, present an opportunity to advance what Batchen terms “a vernacular theory of photography”: using vernacular practices to understand a photographer’s work. This sort of analysis broadens perceptions not only of the medium, but also of the people who use it to be seen.

From the start, Meiselas showed an interest in helping communities tell their stories. In 1974, when Meiselas was teaching photography in an elementary school in South Carolina, she got to know her surroundings by taking pictures, a process that included an initial conversation, a click of the shutter, and, eventually, giving people a print of the photograph she had taken. The final step, in her view, was the “most important.”

Her peregrinations eventually led her to Lando, a small South Carolina town around an abandoned cotton mill where, through the local preacher, she embarked upon her first “community work”: a project that Meiselas conceives and orchestrates but that members of the community bring to fruition. After making a few of her own pictures, she taught some local teenagers how to photograph their families and neighbors using Polaroid instant cameras. They also collected stories about how families had originally come to Lando, who had left, and what had happened to them. Meiselas then helped them organize the materials they had gathered into displays around town to celebrate Lando’s bicentennial. Polaroid snapshots of friends and relations hung in grids on billboards at the roadside. Other pictures were arranged into family trees on walls and billiard tables in the community center. Listening stations accompanied the pictures, playing anecdotes about the people represented in the clusters of photographs around the room. Meiselas’s documentation of the town-wide exhibition shows residents reveling in coming together to see themselves portrayed. These photographs were eventually featured in her 2018 retrospective at the Jeu de Paume in Paris, one of the premier exhibition venues for the art of photography. Thanks to Meiselas, the ordinary photographs of an American town made their way into art history.

Meiselas’s use of Polaroid photographs throughout her career points to the value she places on photographs as objects that can earn a community’s trust and, eventually, help them represent themselves using their own visual language. In 2004, she was one of three photographers commissioned by the Centro Cultural de Belem in Lisbon to create new work for an exhibition that looked at Portugal from the 1950s onward as seen by photographers at Magnum. A selection of archival images by Bruno Barbey, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Inge Morath, among others, which was exhibited inside the museum, showed black-and-white scenes of Portugal in the past. Meiselas’s project, in contrast, invited viewers into the streets of Cova da Moura, a working-class suburb of Lisbon, where displays of instant photographs in color showed the vibrancy of a community that was typically disregarded.

Wandering through the neighborhood, Meiselas encountered a young man who, she recalls, had a camera on his cellphone, which he was proud to show her. But, she observed, “he clearly had never watched a Polaroid print develop in his own hands.” Once he recognized himself in the photograph, Meiselas signed it, added his name, and gave him the print to keep. Their interaction sparked a series of similar encounters in which a photograph—a tangible trace of a relationship, however brief—helped Meiselas earn the community’s trust.

It worked.

She then taught the residents of Cova da Moura to make pictures of their families and friends using instant cameras, which Canon supplied for the occasion. Rather than add written or recorded stories to their photographs, participants wrote their names on the prints’ white borders, another physical trace of individual identity.

Meiselas’s collaboration with the community culminated in an exhibition that demonstrated how photography can become part of the local visual vernacular. Residents celebrated their collective involvement in the project by displaying their prints and a selection of enlargements throughout the neighborhood. Visitors were offered a map to ensure they could see the local community whose photographs adorned walls, plastered electric poles, and hung from windows, balconies, and even clotheslines in Cova da Moura’s streets. For a moment, their vernacular became the official language of the Portuguese art world.

The value of vernacular photographs to represent and bind a community, especially one forced to exist as a diaspora, lies at the heart of Meiselas’s most ambitious project, Kurdistan. When the Gulf War began in January 1991, Meiselas, like most Americans, knew very little about the Kurds. She began learning their story during a brief trip to a Kurdish refugee camp in a “liberated” zone within northern Iraq. The Iranian government had granted her a five-day visa to document for the Western press the Kurds’ increasing need for humanitarian aid. While the world focused on their flight from their homeland, Meiselas turned her attention to the places the Kurds had been forced to leave behind and, eventually, the photographic traditions that bound them as a community, historically and in their present state of dispersal.

Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

The photographs Meiselas took of the Kurds she encountered in Iraq make plain the omnipresence of photography in their daily lives. In one image, a makeshift photo studio in Erbil, in the north of the country, welcomes customers, like the soldier pictured, to have their portraits taken in front of idyllic backdrops. In an instant, the camera transports them to picturesque worlds where calm lakes and sun-filled parks temporarily replace the signs of war and mass killings that scar the actual landscape. In another view, a group of men clusters around a black-and-white photograph that portrays one of them as a Peshmerga fighter in the 1963 rebellion. He holds the photograph gingerly with both hands, taking care to touch only the edges, a gesture that conveys his pride not only in his martial accomplishments, but also in the photograph itself.

A chief aim of Meiselas’s Kurdistan project was to gather families’ personal photographs into a public archive that could become a starting point for constructing a Kurdish history. Western accounts of the Kurds from the 19th century onward rarely refer to Kurdistan as a distinct place, Meiselas discovered. Instead, the history of the Kurds must be pieced together from histories of the numerous countries where they live as cultural minorities. What is more, historic photographs of the Kurds are typically considered ethnographic documents or aesthetic objects, rather than visual records of people with their own identity. Even though the Kurds can be seen in these photographs, their history and culture have remained invisible.

Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

To address this lacuna, Meiselas began amassing Kurdish family photographs and information about the lives of the people pictured. Recognizing the value of the photographs to the families to whom they belonged, she used a Polaroid process to photograph their photographs, usually as part of visits that included long conversations over communal meals. Families thus kept their originals while her copies formed the basis of a book, a series of exhibitions, and a website that presented to the world the collective memory of a community with no official record of its own.

In 1978–1979, Meiselas had spent six weeks in Nicaragua as the Sandinista rebellion against the Somoza Regime was gaining momentum. While there, she inadvertently made a photograph that triggered a proliferation of vernacular photographs, which led her image to become a symbol of the revolution.

“Not a war photographer” by her own definition, she initially took pictures of scenes that illustrated the pregnancy of the moment—a boy eyeing toy soldiers at a market, armed forces in uniform walking in formation, a young man with a rock in his hand and a makeshift mask covering his face. When the simmering unrest erupted into full-blown combat, Meiselas threw herself into the fray to chronicle the range of emotions that war elicits—anxiety, exhilaration, terror, grief.

In July 1979, as President Anastasio Somoza Debayle prepared to flee the country for good, Meiselas took a photograph of a Sandinista rebel, Pablo Jesús Arauz, known as “Bareta,” throwing a Molotov cocktail. The image went viral in the way a photograph could at the time. Photographic reproductions of “Molotov Man” appeared on murals and T-shirts, in advertisements and brochures. A figure synonymous with the incendiary nature of revolution, he emblazoned the tops of matchboxes. The flurry of popular reproductions of Molotov Man throughout Nicaragua made him a national symbol. Even the official insignia designed to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Sandinistas’ triumph featured his likeness. Rather than incorporate other peoples’ vernacular images into her photography, Meiselas in this instance took a photograph that became an icon of vernacular imagery.

Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

After a career traveling the world to help people present themselves as they wish to be seen, Meiselas recently turned her attention to the photographic practices that flourish in her own neighborhood. Last year she published a book based on collections of photographs taken by Italian immigrants on the rooftops of New York’s Little Italy, where she has lived in the same apartment since 1974. Tar Beach marks a capstone to Meiselas’s engagement with vernacular photographs both as objects and as markers of the spirit of a community. In many ways, the book looks like any other family photo album, bringing together snapshots taken by mothers and fathers, daughters and sons from the 1940s through the 1970s. The pictures commemorate events as significant as weddings and first communions and as commonplace as showing off a new bathing suit.

The photographs, which Meiselas and two neighbors collected from local families, show the resilience of a community over time. Earlier images are black and white and dog-eared; later ones are shot in color, many using the Polaroid instant photography process that Meiselas favors in her work. Judging by the photographs, people are rarely alone on Tar Beach. Families gather; friends convene; couples spend an afternoon together. Of course, even pictures of individuals include the presence of the photographer. Photographs stand “as evidence of [an] encounter,” Meiselas has remarked about her medium. The photographer may be invisible, but she is there nonetheless.

As a collection, the photographs in Tar Beach illustrate how a community is far more than a group of people who gather in proximity. Communities bring together likeminded people and those related by blood or by law who rarely see eye to eye. They comprise people who worship together, frequent the same places, or enjoy the same pastimes, in person, on the phone, or, as we’ve experienced in recent months, online. Considered against the backdrop of the pandemic and this year’s social unrest, Meiselas’s representation of one community’s rooftop rituals reminds us that even this period of isolation and turbulence has been one we’ve experienced together. And that no matter what neighborhood we live in, we all have a right to be seen.