The Book That Changed America: How Darwin’s Theory of Evolution Ignited a Nation by Randall Fuller; Viking, 304 pp., $27

What a beautiful thought: that one book, and even a single copy of one book, can change the course of history! In December 1859, Harvard botanist Asa Gray received a copy of Origin of Species from his friend Charles Darwin. Weeks later, Gray’s marked-up copy had made its way to the radical abolitionist and schoolmaster Franklin Benjamin Sanborn in Concord, Massachusetts, delivered there just in time for dinner on New Year’s Day 1860, by Charles Loring Brace, Gray’s cousin and the founder of the Children’s Aid Society. Sanborn’s other guests that night were Bronson Alcott, the quirkiest of the transcendentalists, and Henry David Thoreau, easily the most original thinker of the lot. No one was interested in the food that night, writes Randall Fuller. Instead, the men in Sanborn’s Concord parlor, with the notable exception of the somewhat befuddled Alcott, fed upon ideas. They “supped,” says Fuller, on the power of Darwin’s theory. America was never the same again.

Or was it? Fuller has a compelling story to tell, and he tells it well. His narrative is lush with memorable detail, and his best sentences have the force of proclamations. He is a master at making his characters come alive. A few quick strokes of Fuller’s pen and we see Alcott before us, his face, with its watery blue eyes, resembling “a rumpled pillowcase.” And whereas Alcott drifts through life obliviously, beautifully, like one of Thoreau’s beloved water lilies, the permanently dour Emerson shows up at unexpected moments looking like a “stork in a frock coat.” My favorite character is Asa Gray, lithe, short, energetic, all of his 135 pounds vibrating and his head bobbing from left to right as he begins to talk, way too fast as always, “his tongue tripping over his thoughts,” as if there were a race to win.

Oddly, Fuller’s book is a timely one. Who these days wouldn’t like to believe that history is driven by big ideas, that it is not a series of mishaps, stumbles, disasters barely averted—or not? That it was Origin of Species, read and admired by a handful of progressive Americans during one long winter, that yanked the transcendentalists out of their obsession with the Spirit, gave Louisa May Alcott the courage to write about sex, and mapped out a better future for the soon-to-be-freed slaves? But however much I would like to be convinced, the devil on my right shoulder keeps telling the angel crouching on my left to be quiet—and as usual, that devil has done his homework. The truth is, whatever transpired that night in Sanborn’s house probably did very little to influence the thinking of Americans. Whatever changes evolution wrought in America were the result of hard, patient work by many people, work that had begun before Origin was published, when, for example, the collections made by Charles Wright allowed Asa Gray to theorize, beginning in the mid-1850s, that the surprising similarities he found between the vegetation of the eastern United States and eastern Japan were the result of a common origin. Or when Louis Agassiz, later to become Darwin’s archenemy, encouraged him to undertake the research on barnacles that paved the way for Origin.

Like his characters, Fuller is committed to one big idea—and his adherence to it forces him to cut corners. His supremely sympathetic reading of Louisa May Alcott’s first published novel, Moods, for example, culminates in the assertion that the book’s ending is likely Darwinian. However, in the novel’s original version, Alcott’s protagonist Sylvia refuses to “fill [her] place bravely,” as she is told she must. This to me seems less an acceptance of nature than a bold refusal to live out one’s biological destiny. By contrast, Fuller’s descriptions of the less appealing characters—those who resisted the inevitable forward march of Darwinian evolution—are rife with mockery. Louis Agassiz appears as a cigar-puffing buffoon, discredited as a scientist and too arrogant to realize it, outdone in cluelessness only by Alcott, who thought that human beings had been created first. Agassiz’s long, painful decline had been years in the making, the result of a lethal mix of ruthless ambition and pandering to audiences. Yet when he died, most of the prominent American scientists teaching at important universities—from Addison Verrill at Yale to Burt Wilder at Cornell—were his former students. A central part of Agassiz’s legacy, from which Darwin had profited too, namely the emphasis on exacting fieldwork, lived on. (Fuller doesn’t mention that Darwin continued to write to Agassiz, asking him, as late as 1868, about such details as the coloration and head crests in Amazonian fish.) Although many of Agassiz’s students defected early on to the Darwinian camp, his former disciple Nathaniel Southgate Shaler, a professor of geology at Harvard, nimbly fused some evolutionary and neo-Lamarckian ideas into a form of racial polygenism that was no less noxious than that espoused by his former mentor.

Maybe, given the right circumstances and the right people, Darwin’s Origin of Species really could have changed America. But it didn’t. Gray, for all his support of natural selection, couldn’t ultimately let go of a benign creator; Emerson never distanced himself from Agassiz’s horrifying theories of racial mixing; and Thoreau, perhaps the only character in Fuller’s book who was fully Darwin’s intellectual peer, did not have enough time left to apply what he had learned from Darwin to his research on the distribution of seeds in the forest. On a larger scale, the benefits slaves gained from emancipation yielded only too quickly to what the African-American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar called the “sly convenient hell” of Jim Crow.

About halfway through his book, Fuller mentions a short review of Origin of Species published in Dial, signed by someone who mysteriously gave only his initials, M. B. B. After offering some halfhearted praise, M. B. B. stated his aversion to Darwin’s materialism and quoted Thoreau to bolster his argument that accepting natural selection would destroy any appreciation of nature’s beauty and especially of the human form, which, as everyone knew, was made in God’s image. Darwin’s theory would, M. B. B. said, give us a world populated by Calibans. But who was M. B. B.? A Thoreau-loving creationist? Fuller doesn’t tell us. In fact, he was Myron Beecher Benton, a poet and farmer from the Webutuck Valley, New York, a close friend of naturalist John Burroughs and an avid correspondent with the transcendentalists, a man not given, in the words of a friend, to “worrying about the universe.” As it turns out, Emerson was a great fan of Benton’s work and had memorized large sections of his poem “Orchis,” a fond celebration of how everything in the forest, even the shyest orchid, has been put there for us to find: “Rarest, dream-odored, delicate flowers, sisterhood fairest— / Found by thy prescient search, as gold by the pale treasure-seeker!”

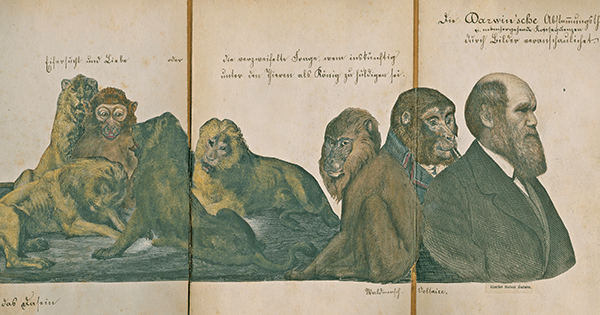

A century and a half later, we are still much closer to Benton of Webutuck Valley than to Thoreau of Walden Pond. A recent study conducted by the Pew Research Center revealed that only a minority of Americans accept the scientific validity of natural selection. As Fuller’s book unintentionally reminds us, we still haven’t quite absorbed Darwin’s central message that things in this world don’t tend to arrange themselves around one big idea or, for that matter, one big book. History, like nature, just is.