One of my first academic positions was as a visiting professor at a large university in the Midwest. Among my other responsibilities, I supervised 11 PhD students in the planning and teaching of a multisection course called Major Figures in Western Literature. Each semester, the students had to select an archetypal character (such as the Lover, the Outsider, or the Fool) around which to base their readings. When I supervised the course, the character they chose was the Imposter. As the epigram for the syllabus, they chose a line from Oscar Wilde’s 1891 essay “The Truth of Masks”: “Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth.”

The Imposter was an excellent choice, but then this was a smart, sophisticated group. All the instructors were fluent in at least two languages, and although still young, they were serious and hard working, with a quiet, grounded confidence that I envied and admired. The Imposter was intended as a college-wide requirement for freshmen non-English majors, and for this reason, I suggested it might be best to choose accessible, contemporary texts such as movies and short stories. But for the most part, the instructors ignored my advice and gravitated toward the ancient and classical texts they were most familiar with. The syllabus they put together began with a translation of Plautus’s Latin play Amphitryon, and included stories from the Thousand and One Nights, the tale of Cupid and Psyche from Apuleius’s The Golden Ass, Molière’s Tartuffe, and—in a concession to the modern age—Kurt Vonnegut’s Mother Night. Each text had its proponents and detractors, but there was one we all agreed on: Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Our meetings took place in a small, book-lined conference room normally used for private tutorials and thesis exams; it was too small for our group of 11, and we had to squeeze into corners and perch on top of cabinets. On the day we met to discuss the structure of the syllabus, I was squashed in a corner and recall feeling slightly disengaged from the group, thinking that my presence wasn’t really necessary. After all, the graduate students were perfectly capable of planning the course on their own. They all seemed so much more serious and devoted than I had been in graduate school—to their research, yes, but also to life in general. They never seemed to spend time dating, drinking, traveling, or socializing. Those who were in relationships seemed to be either engaged or married; one couple already had young children. They all seemed so focused, whereas I found myself constantly sidetracked by unrelated trains of thought.

For example, one of the instructors insisted on pronouncing the name “Jekyll” as “Jee-kill.” She said she had looked it up and that was the way Stevenson himself had pronounced it. She is right, but I found her pedantry irritating, and was glad no one else pronounced the name “correctly.” This was the same woman who, whenever anyone inquired about the subject of her thesis, rather than simply saying “Ibsen,” would always reply, “Henrik Ibsen,” which in her southern accent sounded like “Henry Gibson” and made everyone ask, “Oh? Who’s he?”

Another thing I started to wonder is why everyone always says, “Robert Louis Stevenson,” never just using the last name, as they did with Plautus, Apuleius, or Molière. The name is not so common that people would not know whom you mean—I cannot think of any other famous authors named Stevenson—but still, whenever I said “Stevenson,” someone else would always add, “Robert Louis Stevenson?” It is one of those names that you only ever seem to hear in full, like Edgar Allan Poe or Arthur Conan Doyle.

That my mind kept going off on these kinds of tangents made me feel like a bit of an imposter myself. This impression increased when, arriving at the department’s annual winter gathering, I found that the choice of beverages was limited to Coca-Cola or orange soda. In the United Kingdom, even as an undergraduate, I was used to being offered at the very least a glass of lukewarm mulled wine or stale sherry by my professors at our Christmas party. I had been unaware until now that I was working on a dry campus; in fact, it was the first time I had ever heard the phrase. My previous job had been at a university in London that had a student-run bar. On warm days, we’d hold our classes on the grass or picnic tables outside, and at the break, students would bring out trays of beer. Here, if I wanted a drink, I had to leave campus and find somewhere in town.

Of course, that was not difficult to do. What was more difficult was to separate, for the first time, my “private” self from my “professonal” persona. Although I was younger than many of the instructors, they would defer to me politely as the course supervisor, and I found myself dressing and behaving differently as a result. I felt as though I had to set an example, to play the role of a professor in a more obvious manner than I normally would. I wore heels, ironed my skirts, and did not ride my bike to work, or bring my dog. What furthered the divide was that I was given my own office, something I have never had before or since.

This issue of the private and professional self is at the heart of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. I’d read Stevenson’s novella when I was a child, and again as an undergraduate, but retained so little that I felt as if I were reading it now for the first time. Jekyll and Hyde came to life for me that year partly because I was in the right frame of mind to think about it seriously, and partly because it was so different from the story I thought I knew. For one thing, there is nothing noticeably ugly about Edward Hyde; he is not visibly hairy and ape-like, he does not have fangs or bad teeth—he just gives everybody the creeps. “There is something wrong with his appearance; something displeasing, something downright detestable. I never saw a man I so disliked, and yet I scarce know why,” says one man who meets him. “He gives a strong feeling of deformity, although I couldn’t specify the point.” Although Mr. Hyde is a man who looks as if he “must have secrets of his own; black secrets,” he is not physically repulsive, as he appears in so many stagings.

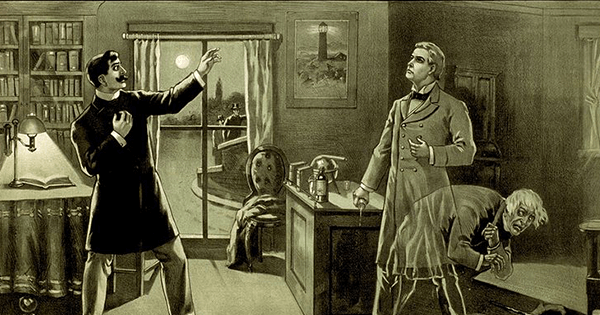

Stevenson’s novella isn’t a mystery or horror story, but a psychological case study, as its title suggests. Yet the mood is dark, and one especially scary moment occurs in a brief chapter called “Incident at the Window.” One Sunday, at twilight, Jekyll’s friends Mr. Utterson and Mr. Enfield are walking past the back entrance to the doctor’s premises, and, “uneasy about poor Jekyll,” they decided to step into the courtyard. Looking up, they notice that the middle one of the three windows is half open, and sitting close beside it, “like some disconsolate prisoner,” is Dr. Jekyll.

The two men invite Jekyll to take a walk with them, but the doctor admits to feeling “very low.” Utterson makes a few encouraging remarks about Jekyll’s health, suggesting that he has been working too hard and should spend more time out of doors. Jekyll smiles at him, but all of a sudden, “the smile was struck out of his face and succeeded by an expression of such abject terror and despair, as froze the very blood of the two gentlemen below.” The horrible expression on Jekyll’s face is glimpsed only for a moment, then the face disappears and the window is “instantly thrust down.” The men look at each other, both pale, and see an “answering horror” in the other’s eyes.

Things glimpsed peripherally can often seem more frightening than things faced head-on. There is something uncanny about them—they make us second-guess whether we really saw them, forcing us to question the reliability or our senses. Normally, we sift through all external stimuli, reject the bits that unnerve us, and accept whatever makes us feel most comfortable. We build our own worlds to live in, actively putting together a relationship to reality that we can maintain and that sustains us in turn. The sight of something uncanny slips through the cracks in the armor we have built ourselves, reminding us that our world is not as stable as we like to pretend it is.

It felt strange to be thinking about the instability of my world while living in this verdant and fertile Midwestern college town, where I spent much of my spare time exploring the quiet tree-lined streets, stopping to gaze enviously at the rambling old houses with their wooden porches and Dutch gables. Strangers raking leaves or walking their dogs would greet me as I passed by; occasionally I would hear the sound of someone playing the violin or practicing scales on the piano. When I tried to imagine the kind of people that lived in those houses, I always imagined academic couples with their sensitive children, sweet au pairs, and music lessons. I imagined kind, thoughtful, loving people. It was difficult to picture them being unhappy.

Of course, I knew this was a fantasy. There are crimes, accidents, and tragedies everywhere, and college towns have more than their share. On Independence Day weekend that year, I came home to find the end of my street cordoned off with crime scene tape and policemen all over the neighborhood. A white supremacist on a two-state shooting spree had shot and killed a student at the Korean church a few blocks away. The gunman committed suicide two days later.

One day before the semester had ended, I found a letter that had been slipped under my office door. It was a long, heartfelt, anguished mea culpa from a PhD student I will call Hans, a young man so absurdly tall, blonde, and handsome that I thought of him privately as Der Übermensch. This upright young man had been born and raised in Europe. He was unapologetically Christian (his parents served as missionaries), and in his letter, he confessed that his personal convictions had made it impossible for him to teach certain texts on the course syllabus. He had a particularly strong objection to Mother Night, whose protagonist commits suicide at the end of the book. Hans felt this scene might exert a destructive influence on vulnerable undergraduates; consequently, without asking permission, he’d replaced Mother Night with Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day, which he felt to be a safer choice.

I failed to see how The Remains of the Day would be less disturbing than Mother Night, nor could I help wondering what had led Hans to write such a letter this late in the semester—or even at all, since his textual substitutions, harmless in themselves, would otherwise have gone without notice. Perhaps he felt the sting of conscience. Maybe he had prayed about it. Either way, his letter was a strange combination of apology and declaration of war. While remaining convinced he had done the right thing, he also confessed to feeling guilty about taking matters into his own hands. He should, he admitted, have come and talked to me about his ethical objections. I admired the strength of Hans’s convictions, but I also wondered why someone with his firm moral principles had chosen to do a PhD in comparative literature. And why write me this letter, rather than approaching me directly? Perhaps, like many scholars, he felt more comfortable writing than speaking. By letting me in on his secret after the fact, he made it too late for me to do anything other than accept his textual switch—a strangely passive-aggressive act for someone who seemed so straightforward and fond of honesty. He had, I felt, much greater battles to come.

As part of my supervising duties, I visited each of the 11 class sections, and during the week dedicated to Jekyll and Hyde, sat in on a class taught by a shy instructor whom I’ll call Matt. He was a popular and dedicated teacher, though visibly nervous (disarmingly, at one point he accidentally referred to Jekyll and Hyde as Heckle and Jeckle, which made his students giggle). After his class was over, since it was a Friday evening, we decided to go and get a drink—something stronger than orange soda. We went to a bar in town, where, sitting in a back corner, we got into a long discussion about literature and life. Matt, I learned, was a voluminous reader with an undergraduate degree in music (he played classical guitar) and a deep interest in comparative mythology. Although laconic, he was also funny and self-deprecating. I liked him a lot, and the feeling seemed to be mutual. In short, we stayed too late, drank too much, and spent the night together.

On Saturday morning, we both felt hung over and a little sheepish, though the mood between us was playful and affectionate. Matt had a craving for pancakes, and we went to get breakfast. We sat facing each other in a booth. He asked me if I wanted to see him again, and I said I did but that we ought to keep it under wraps, at least while I was still supervising the graduate course. Matt agreed. I was sitting with my hands on the table in front of me, and Matt took my right hand in his and held it for a while, touching my fingers, playing with my rings.

The following Monday, I left my office door open so I could hear the ping of the elevator doors and see Matt as he arrived for our department meeting. Just before noon, I heard some of the graduate students getting coffee in the lounge area outside my office. Recognizing Matt’s voice, I went to the door and asked if I could speak to him for a moment. He followed me inside, clutching a French dictionary stiffly to his chest, and left the door open. I sat down and pulled a chair up for Matt, but he didn’t sit down and wouldn’t meet my eyes.

I suddenly realized what was coming. It wasn’t the first time I’d been brushed off—I’d done it myself, so I knew how awkward it could be—but in this case, I was taken by surprise. We’d had breakfast together, we’d talked things over; I thought I knew where I stood. Now, as Matt stood clutching his dictionary, averting his eyes and muttering about keeping his focus on his work, I was completely at a loss. I was surprised, then, at how quickly and automatically my own mask slipped into place, after he made his hesitant disavowal. He could not, he realized, mix his work with his private life.

I agreed, and, observing Matt’s undisguised relief, showed him out and closed my office door. The whole thing had taken two minutes or less.

I used to refer to a person who has two completely different sides to her character as someone with “a Jekyll-and-Hyde personality,” but I now realize the expression is inappropriate—for Jekyll and Hyde share the same mind. Only their bodies are different. Jekyll creates Hyde because he is unable to repress and compartmentalize. He cannot relax into the everyday hypocrisy enjoyed by his fellow middle-class Victorians. He is too worried about being discovered, too concerned about his reputation to enjoy his sins. In the same way, I can see in retrospect that the sweet, playful Matt of Friday night was another manifestation of the reticent, standoffish Matt of Monday morning. With hindsight, his change of heart is easy enough to understand. Sex and alcohol make an intoxicating brew that, unlike Dr. Jekyll’s potion, does not always wear off right away.

I cried in my office for a while, then washed my face, put on some lipstick, took a deep breath, and not wanting to let the pain of rejection show, put on my best professional mask. I do not know whether Matt said what he did to let me down kindly, or whether he really believed it; whether it was for professional reasons (he felt it could be damaging to his career), or personal ones (he was unable to separate his relationship with me as an adviser with his romantic interest). Whatever the reason, he was more mature than I was. I realized then that I, too, had to learn to be an imposter, to build walls, to compartmentalize, to repress my emotions. In other words, I needed to behave as an appropriate adult—which is another way of saying to learn how to lie. “A short primer, ‘When to Lie and How,’ if brought out in an attractive and not too expensive a form, would no doubt command a large sale, and would prove of real practical service to many earnest and deep-thinking people,” writes Wilde in “The Decay of Lying,” an essay published in the same 1891 volume as “The Truth of Masks.” Hans and I could both have used such a book.

Ironically, earlier in his essay, Wilde criticizes Stevenson’s novella for being too realistic, complaining that, “the transformation of Dr. Jekyll reads dangerously like an experiment out of the Lancet.” He argues that what makes life interesting is not reality but illusion; what is interesting about people “is the mask that each one of them wears, not the reality that lies behind the mask.” Behind the mask we are all alike; in order to coexist, we must repress and deny this fact. And so we pretend otherwise, making compartments and borders, levels and hierarchies. Eventually, if our imposture is successful enough, we learn to become strategic rather than intimate in our revelations and relationships. We develop a workplace version of ourselves that is neat and professional, that does not spill over the edges into betraying emotional neediness, instability, or desire. To successfully negotiate both public and private worlds, we must learn to lie. To be truly effective, however, we must learn to deceive even ourselves.