Sex Workers of the World United

Last year’s SESTA/FOSTA legislation aimed to limit sex trafficking—but it’s just the latest in a long line of policies designed to criminalize the oldest profession

On a cool, slightly breezy January day in San Francisco, several hundred female sex workers assembled and began to march. Decked out in colorful clothes, some wearing elaborate hats, the women trooped through the city’s Upper Tenderloin neighborhood, past a pair of police officers, and into Central Methodist Church, at the corner of O’Farrell and Leavenworth streets. Some of the women were old, some were young; some were white, many were not. All of these sex workers were in Central Methodist that day to confront the Reverend Paul Smith, who had been crusading for a police crackdown on prostitution. Once the women had settled into the pews, a locally famous madam known as Mrs. R. M. “Reggie” Gamble rose and began to speak.

Gamble addressed herself directly to Smith: “I want to ask first, how many of the women in your church would accept us into their homes—even to work? You would cast us out—where to?” She continued in her deep, sonorous voice: “Every woman here has at least one child. We are against street walking … as well as you. But what are you going to do about it? … I am a mother of a girl of 14. Another girl in my house is the mother of four. She was sick. She wrote to her brother, a Methodist preacher, for help. He answered, ‘trust in the Lord.’ ”

All eyes turned to the reverend. He began posing questions to the assembled women. “How many of you are in this life because you could not make enough to live on?” he asked. All hands went up. Yet it clearly wasn’t just poverty that led women to sell sex. How many would rather do housework? Smith asked. His question was met with a roar of laughter. One woman shouted back, “What woman wants to work in a kitchen?”

One day last June, in New York City’s Washington Square Park, this scene largely repeated itself, except that unlike the temperate conditions of a Bay Area winter, it was a blistering 90 degrees. Hundreds of sex workers and their allies gathered to protest the criminalization of prostitution and other forms of sex work. They wore colorful clothes and held red umbrellas and evocative signs. “Criminalization Kills!” read one. “The Only Good Cop Is A Stripper Cop,” read another.

The sex workers—mostly women, but also many men—began to march. They made their way around the park to its iconic marble arch. As they walked, they began to chant in unison: “Sex workers, survivors, united.” The marchers gathered in a circle as members of the crowd moved forward to give speeches. They decried recently enacted laws that would make it harder for them to coordinate the sale of sex from the safety of their homes. They spoke against police violence. After 90 minutes, the crowd began to disperse. “People hugged and in many cases wiped away tears,” journalist Zoë Beery reported in The Outline.

Those two demonstrations took place more than a century apart. The San Francisco march happened in 1917. The parallels between the two, however, are striking. Both were female led, both featured a diverse array of prostitutes and other sex workers, both took place in metropolises famed for winking tolerance and brutal repression—and both demonstrations were in response to specific policies that had been proposed in the name of helping sex workers.

In San Francisco in 1917, Reverend Smith insisted that shuttering brothels and locking prostitutes away in a “state industrial farm” would be for their own good; it would make them safer and less vulnerable to exploitation. “I am not in a crusade against you women or commercialized vice in San Francisco,” he told the throng of sex workers in his church. “No person in the world has more sympathy for you girls than I have. The problem of commercialized vice is a man problem. Men are making the money out of it.”

In New York, the demonstrators were gathered for International Whores’ Day (also known as International Sex Workers Day), which is observed annually. But they were also rallying against the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (sesta) and the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (fosta). These bills, which passed Congress in a combined form nearly unanimously in March 2018, were written with the express intention of shutting down websites through which people sell sex online. SESTA/FOSTA, like Smith’s campaign in San Francisco, had been proposed in the name of protecting sex workers, especially women, from trafficking and abuse.

“We are bringing a bill to the House floor that will protect the fundamental rights of victims of sex trafficking,” declared Republican Representative Ann Wagner of Missouri, in proposing FOSTA. “Online trafficking is flourishing because there are no serious, legal consequences for the websites that profit from the exploitation of our most vulnerable.” Previously, websites on which sex workers advertised their services were immune from prosecution because platforms were not held responsible for the actions of individual users. Now they could face criminal penalties. President Donald Trump signed SESTA/FOSTA into law last April, to bipartisan fanfare.

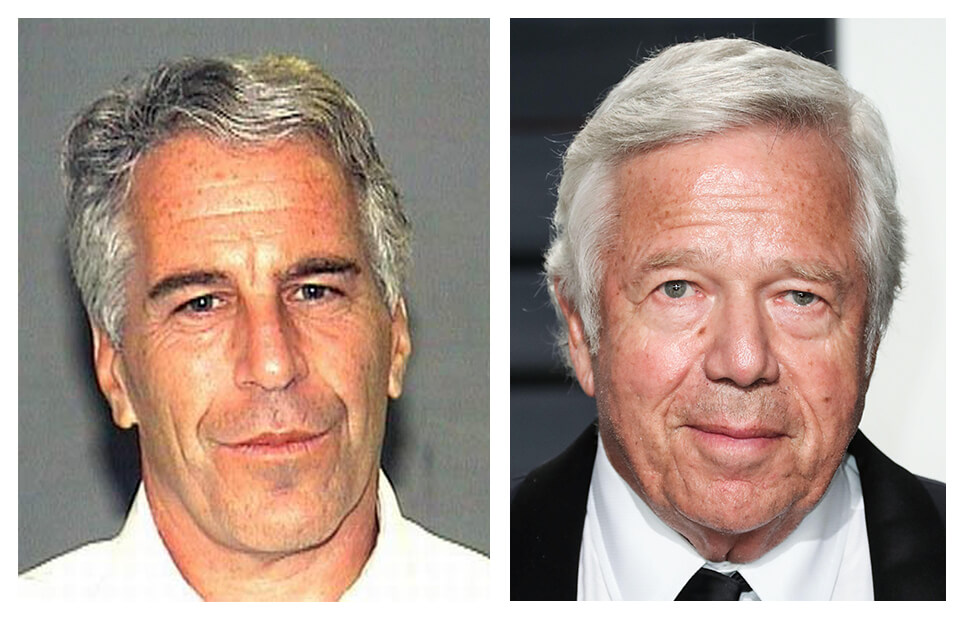

Financier Jeffrey Epstein (left) and New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft were charged with solicitation, and were both offered plea deals. (Archive PL/Alamy; Image Press Agency/Alamy)

Sex trafficking, the illegal transport of people for the purpose of sexual exploitation, is often conflated with sex work, the consensual sale of sex by adults. Except in roughly a dozen rural counties in Nevada, prostitution is illegal in the United States, and separate laws forbid human trafficking. But laws against prostitution often make no distinction between consensual sex workers and trafficked ones and are instead designed to maximize arrests and prosecutions—meaning that many trafficking victims are arrested and prosecuted while the men who solicit sex are let off the hook. The lenient plea deals offered to billionaire and New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft, as well as financier Jeffrey Epstein, are just two recent examples. Meanwhile, sex trafficking survivors who try to protect themselves, like Cyntoia Brown—convicted of murdering a man who had solicited her for sex in 2004—can be sentenced to life in prison. (Brown’s sentence was later commuted, and she is scheduled for release in August.)

Trafficking is real and horrifying. But criminalizing sex work or forcing sex workers onto the streets and under the thumb of male pimps only makes things worse. Trafficking survivors are likelier to go to the authorities if they won’t be thrown in prison—or deported—as a result. And after they’ve escaped their traffickers, survivors have a much easier time establishing a normal life—with safe housing, education, and legal employment—if they have no criminal record.

The way to prevent trafficking is to listen to the demands that sex workers have been making for generations. As trafficking survivor Laura LeMoon has written, “In truth, there is no simple answer to trafficking, which often occurs at the intersection of systemic, interlocking inequalities such as poverty, racism, sexism, and transphobia.” Changing these structural conditions would be a means to ending trafficking, she writes. “Attempting to abolish the sex industry will not stop sex trafficking.”

A century of American history bears out that argument. The new policies in 1917 and 2018 did not protect sex workers or reduce trafficking. Despite the intentions of their creators, both policies ended up making the lives of sex workers more dangerous by pushing them out into the streets—and into the hands of pimps who may turn consensual sex work into coerced sexual exploitation, or traffic them.

The effects of the 1917 policy are clear. Just days after Smith was confronted in his church, the city of San Francisco established a “morals squad” (headed by an ambitious former professional boxer), which was empowered to raid brothels and arrest their occupants. Within a week, practically every brothel in the Upper Tenderloin had gone under; a week later, dozens of policemen raided the city’s other red-light district, known as the Barbary Coast. Every prostitute was given an hour to “pack up and get out.” Male onlookers gathered to watch the women drag suitcases down the street. More than a thousand women lost their homes that night. Reporters later wrote that one question was heard repeatedly: “But where are we goin’ ?”

Prostitution did not disappear from San Francisco. Instead, women who sold sex were simply driven from the brothels and onto the streets. Whereas once they had enjoyed the relative safety and protection of the brothel walls, now they had to work in alleys and on street corners; whereas once female madams had controlled much of the sex trade in the city, now male pimps began taking over. As historian Ruth Rosen has written, prostitutes “became the easy targets of both pimps and organized crime. In both cases, the physical violence faced by prostitutes rapidly increased.” Contrary to Smith’s intentions, more men were making more money than ever from prostitution.

The same dynamic repeated itself in the aftermath of SESTA/FOSTA. Within days of the Senate vote, Craigslist shuttered its “Personals” section. Many websites, including Backpage—a popular site through which sex workers could safely screen potential customers—closed down, either preemptively or by federal order. Once again, sex workers were driven onto the streets—indisputably a more dangerous place to work—and prostitutes were subjected to violent johns who could not be screened, as well as to the police, who have been known to abuse or assault sex workers in addition to arresting them. One survey of sex workers in Alaska found that 26 percent of respondents had been sexually assaulted by the police; another survey from New York found that 14 percent had experienced police violence.

“I’ve had to carry around mace and a taser now, which I don’t want to [do],” one long-time escort told The Outline. “But guys honestly could choke me; I could be robbed by other women or by pimps. It’s [the] wild wild west out here, and it’s really endangering our lives.”

“Community members have died due to this legislation, many people have lost access to the majority of their income and don’t know how they will pay rent,” community organizer Danielle Blunt told Gizmodo in June. “The effect of these bills is vast and devastating.”

As Motherboard’s Samantha Cole reported just weeks after SESTA/FOSTA’s passage, “former pimp[s] are swooping back into sex workers’ lives. They’re capitalizing on the confusion and fear this law has created, as online communities where sex workers found and vetted clients and offered each other support are disappearing. What are you going to do without me, now? exploiters say, flooding former victims’ inboxes and texts. You need me. According to sex workers I’ve spoken with, this is a common message.” Slate, Rolling Stone, the Detroit Metro Times, and The Nation have confirmed such reports.

Despite being billed as transformative by its proponents, SESTA/FOSTA has a long, tired history. It is the product of decades of repressive American laws and policies that were framed as protection but instead caused harm. It is also the product of the centuries-old belief that sex workers should not play a role in shaping the policies that govern their lives. If instead policymakers listened to sex workers, they might understand how ineffective their tactics are. If those who work in the sex trade had a seat at the table—if their voices and experience and wisdom were respected—bipartisan disasters such as SESTA/FOSTA might be averted.

“We want to be let alone,” one woman had yelled at Smith a century ago. “What ship are you going to send us away on?” shouted another. The day after the march in San Francisco, Gamble had an opinion piece published in the San Francisco Chronicle, begging the city fathers to heed her warning. “Remove prejudice from those whose attitude is one of ‘holier than thou,’ ” she wrote. “We have had our experience with liquor, with vice from time immemorial. Nothing dies. Vice does not die any more than another concrete entity. Seek for a better tomorrow. Seek without prejudice to provide against future growth, not to strive blindly to eradicate something of today which conditions and environment have created.”

The authorities didn’t listen.

Sex workers have argued against criminalization of the industry for more than a century, as this 1917 edition of the San Francisco Chronicle shows.

For much of American history, prostitution was a relatively safe and prosperous female-led industry. In the 19th century, as America expanded westward with the brutal rapidity of Manifest Destiny, boomtowns sprang up across the West. Since the populations in these towns were often majority male (most of them unmarried), brothels blossomed like prairie flowers. With limited supply and desperate demand, women could exercise some control over the prices they charged, and 19th-century prostitutes earned significantly more money than any other kind of female laborer.

The sex trade in the West was dominated by brothels, often lavishly decorated, where prostitutes lived and worked. Protected from the elements and from many forms of harassment, workers in brothels were generally both safer and better paid than those working on the streets, historians have found. The madams who often ran these establishments thus controlled much of the sex trade. Thaddeus Russell has described how certain madams became American icons, like Jennie Rogers, the Queen of the Colorado Underworld, who brought in personal hairstylists and dressmakers for her “girls,” and Mary Ellen “Mammy” Pleasant, who was born a slave but rose to become one of the wealthiest and most powerful women in San Francisco.

And, as Russell pointed out, it wasn’t only madams but also the prostitutes themselves who profited from the sex trade. George M. Blackburn and Sherman L. Ricards noted in their study of mid-19th-century Virginia City, Nevada, that prostitutes “amass[ed] more wealth than most of their customers.” Paula Petrik examined the same period in Helena, Montana, and found that about 60 percent of the city’s white prostitutes “reported either personal wealth or property or both.” They were rarely arrested, and proprietor prostitutes made nearly half of all real estate transactions undertaken by women.

Though authorities in the West periodically cracked down on prostitution, they usually chose to let the brothels operate as they pleased—often in exchange for handsome kickbacks. Officials in San Francisco even opened their own “municipal brothel” in the wake of the devastating 1906 earthquake; half of the profits earned by its 133 prostitutes went straight to the city treasury.

Back east, major cities had well-known red-light districts—supposedly named for the red lanterns hung outside brothels. In New York, this district was known as the Tenderloin; in Chicago, it was the Levee; in New Orleans, it was the infamous Storyville, mythical birthplace of jazz. As historian Neil Larry Shumsky has written, these red-light districts thrived on “tacit acceptance,” based on a simple logic: since prostitution was so difficult to eradicate, it could be tolerated as long as it was kept apart from so-called respectable citizens. (The irony, which some madams delighted in pointing out, was that so many “respectable” men visited their brothels under cover of darkness.)

Timothy Gilfoyle has written about “an affluent, but migratory, class of prostitutes” thriving in 19th-century New York. “In a world of imperfect choices, these women did not view prostitution as deviance or sin,” he writes. “Rather, they considered it a better alternative to the factory or domestic servitude.”

But 19th-century prostitution should not be romanticized, and red-light districts were not utopias. Many women were exploited and abused—sometimes by male pimps, sometimes by clients, sometimes by police, and sometimes by the madams themselves. Further, as Rebecca Yamin has documented in “Wealthy, Free, and Female,” her innovative archaeological study of a 19th-century New York brothel, many prostitutes “may have looked wealthy [and] free … from the outside, but an inside perspective suggests their lives were considerably more complex.” Prostitutes used jewelry and fine clothes to attract bourgeois clientele, but many lived no better than “their sisters in the tenements.” And as was true in many other professions, white prostitutes indisputably made more money and endured less official abuse than nonwhite prostitutes.

Still, it is hard to examine even cursorily 19th- and early-20th-century prostitution and not conclude that it was often a profitable vocation that operated largely in the open. “When I look closely at the life stories of poor women during the early years of this century,” wrote Ruth Rosen at the beginning of The Lost Sisterhood, her masterly study of American prostitution, “I am struck again and again by most prostitutes’ view of their work as ‘easier’ and less oppressive than other survival strategies they might have chosen.”

Such relative tolerance began to change around the turn of the 20th century. First in England and then in the United States, a powerful movement of religious activists and elite women united to oppose what they called “white slavery.” The term, which was said to have been coined by Victor Hugo, distinguished between the “slavery of black women,” which had been “abolished in America,” and the “slavery of white women [that] continues in Europe,” according to a pamphlet from 1902. Tales of virginal young white women kidnapped and sold into sexual slavery—sensationalized, and in many cases demonstrably false—were read by hundreds of thousands in England, and activists seized on public anger to demand an end to the tacit acceptance of prostitution.

The battle soon spread to the United States. Prominent men and women invoked the fiery religious language of the crusade against white slavery and demanded that all brothels be destroyed. In Los Angeles, for instance, hundreds of church workers marched into the red-light district, trying to “rescue” prostitutes from white slavery and preparing churchgoers for the “Battle of Armageddon.” In 1909, a minister named Sidney C. Kendall led his riled-up followers to help initiate a recall election against Los Angeles mayor Arthur Harper, who, along with some of his police commissioners, was accused of selling worthless stock shares to brothels in exchange for protection (alongside a string of other industry-enriching privatization schemes). The mayor resigned before the recall vote could take place, and his successor, George Alexander, promised to “rid the city of prostitution.” Immediately, the police began raiding brothels and forcing their residents into the street. The city council passed an ordinance making it “unlawful for any woman to offer her body for the purpose of prostitution.”

Such closures did not end prostitution, however. According to Los Angeles policewoman Aletha Gilbert, the prostitutes in Los Angeles simply scattered into “every part of town.” Likewise, in England, the white slavery crusade led to the passage of the Criminal Law Amendment, designed to protect women from trafficking and exploitation. The law enabled the police to search brothels on a whim and made street solicitation a serious crime. Promoted as a way to protect women, it ended up being a cudgel that allowed state authorities to criminalize, stigmatize, and lock up thousands upon thousands of marginalized women.

In 1910, Congress passed the White-Slave Traffic Act, better known as the Mann Act, which made it a federal crime to transport a woman across state lines for “prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose.” The Mann Act’s advocates insisted it would cripple the white slave trade; in reality, it allowed officials to intensify their campaign against brothels and street soliciting. The first arrests made under the Mann Act were a madam and “five apparently perfectly willing prostitutes” traveling from Chicago to Michigan. Women suspected of aiding in the trafficking—or of being trafficked—could be locked up. “The Mann Act had been passed to protect women,” historian Jessica R. Pliley has observed, “yet women increasingly came under its purview. … Even women who were deemed to be victims in white slave investigations faced incarceration.” This fit with the never-ending pattern: the women who sold sex were locked up, while the men who purchased it often got off scot-free. (The Mann Act has also been used to target racial and political minorities, like African-American boxing champion Jack Johnson—posthumously pardoned only last year—and Charlie Chaplin, accused of being a Communist.)

The fight against white slavery was ostensibly a fight against sex trafficking, and although modern historians agree that some forced prostitution existed during these years, the amount was greatly exaggerated by anti-prostitution crusaders. Furthermore, no evidence suggests that in the wake of these laws, trafficking went down. Part of the difficulty of studying trafficking in the early 20th century is the lack of reliable estimates of how many people were actually trafficked, since the crime was always conflated with sex work. But based on primary sources and attention to context, most historians agree that tales of trafficking were hugely exaggerated, and that the reports of vice commissions were overblown.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries also witnessed the rise and consolidation of urban “machine” politics, which led to more male control over the sex trade. Political bosses, sometimes with ties to organized crime, consolidated power over prostitution in many cities, with underlings exploiting any commonalities of language or national origin they shared with women who were new to the United States or else excluded from the mainstream labor market. This, in turn, led those campaigning against white slavery to likewise decry the “vice trust,” or otherwise invoke the specter of some ethnic political boss controlling the traffic in white women. The white slavery crusade thus reflected racist and anti-immigrant sentiments and, frequently, a bitter anti-Semitism (“It is an absolute fact that corrupt Jews are now the backbone of the loathsome traffic,” declared McClure’s magazine in 1909).

Finally, the fight against white slavery, and the concomitant crusade against prostitution, reflected a fear of sexually active young women. The turn of the 20th century was a time when more women were becoming formally educated and beginning to demand the vote and a political voice. Rates of premarital sex and divorce were rising steadily. The fight against female-run prostitution was one aspect of the patriarchy striking back.

The American entrance into World War I in 1917 provided the impetus for the expansion of isolated municipal campaigns against brothels. But as in Los Angeles a decade earlier, this crackdown did not eliminate prostitution. “In most cases,” Rosen writes, “thousands of prostitutes simply left town and went to another city where the local vice district remained open.”

In the name of protecting soldiers and sailors from prostitutes, the War Department demanded that hundreds of cities shutter their brothels and crack down on prostitution—which hundreds did. Federal agents, state police, and local officials began combing the streets, looking for women, some newly expelled from brothels, who were trying to feed and clothe themselves by selling sex. By the end of the war, tens of thousands of women had been locked up for practicing prostitution—or for having sexually transmitted infections, or for simply being promiscuous. The American Plan, as this crackdown was later known, was in effect about controlling female sexuality.

After the war, dozens of cities across the country continued to detain and examine women by the thousands. The Great Depression broke the policing fever, to some extent, as many cities ran out of funds with which to imprison so many women. Prostitution was tacitly accepted again, and some brothels returned. However, male pimps had gained power during the previous two decades, and men now dominated much of the sex trade.

Yet even as policing diminished in the United States, calls for the suppression of trafficking continued. The newly formed League of Nations dedicated itself to combating forced prostitution and in 1921 established an Advisory Committee on the Traffic in Women and Children; the term “traffic” had largely replaced “white slavery.” But in 1923, the American delegate to this committee, Grace Abbott, suggested that it examine the true extent of forced prostitution: “Do we really know that the traffic exists at all?” At her suggestion, the committee created a Special Body of Experts—staffed by American anti-prostitution advocates—to travel the globe, investigating trafficking in 112 cities and districts, in 28 countries. The subsequent 1927 report was vague about the extent of actual coercion, but it was unequivocal on the general matter of prostitution—unsurprising, given that its authors had been instrumental in the American Plan. “Prostitution should be regarded as a public evil to be kept within the narrowest possible limits,” it read. “Safeguards of all kinds against international traffic are difficult to enforce when the lowering of the standard of morality serves to create an insistent demand.”

The report, despite its somewhat unreliable trafficking data, had tangible effects on policy: at the advisory committee’s suggestion, some countries began arresting women suspected of selling sex. In Cuba, for instance, after investigators from the advisory committee visited, the local police shut down more than 200 brothels and jailed hundreds of women. Hundreds more left the island when they could no longer make a living there.

Two decades later, America’s entrance into World War II prompted a repeat of the previous war’s invasive policing. Once again, tens of thousands of sexually active women—some of them prostitutes, many of them simply suspected of extramarital sex or infected with syphilis or gonorrhea—spent time behind bars. In the postwar years, prominent Americans, including veterans of the wartime campaigns to lock up women, again partnered with international organizations (this time the United Nations and World Health Organization) to draft a new Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Persons and of the Exploitation of the Prostitution of Others. This convention, approved in 1949 and enacted in 1951, demands that signatories punish anyone who “[p]rocures, entices or leads away, for purposes of prostitution, another person, even with the consent of that person” or “[e]xploits the prostitution of another person, even with the consent of that person.” It remains in force, with more than 80 parties to the convention.

Women suspected of prostitution are rounded up in Chicago, c. 1955. Invasive policing had begun again following America’s entrance into World War II. (Kim Vintage Stock/Alamy)

The postwar period also marked the dawn of the sexual revolution. The celebrated studies of Alfred Kinsey revealed that some 70 percent of American men had slept with a sex worker. In 1960, birth control pills became available; in 1964, activists held a “speak-out” at Columbia University, arguing for the legalization of prostitution; in 1967, a sex worker in a mask testified before the Kansas legislature, opposing a bill that would outlaw prostitution. All throughout the 1960s, sex workers took part in uprisings against violent policing, such as those at Stonewall and Compton’s Cafeteria; sex workers of color and transgender sex workers played especially vital roles. Meanwhile, the women’s liberation movement and the nascent gay rights movement publicly demanded recognition of fundamental rights to social and legal equality.

The sexual revolution profoundly altered the status quo of policing and sex work in the United States. Many states halted decades-long enforcement of laws that allowed authorities to detain, examine, and incarcerate “promiscuous” women. Other states, such as New York, debated decriminalization. One observer in New York pointed out that in the late 1960s, “of the total prostitution and patronizing convictions, less than one percent were for patronizing”—that is, the purchase of sex by men.

In the 1970s, former sex workers themselves formed organizations to advocate for decriminalization and for greater economic and civil rights. One such organization, Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics (coyote), successfully (albeit temporarily) halted enforcement of many laws against prostitution in San Francisco, and other sex workers rights’ groups spread across the country and around the world. By the mid-1970s, many public opinion polls showed broad popular support for legalization or decriminalization.

But then, as before, the backlash came. The election of President Ronald Reagan and the rise of the religious right killed much of the momentum for decriminalization. Cuts to welfare and antipoverty programs led greater numbers of women to begin selling sex. And increasing awareness of the hiv/aids epidemic led to new fears surrounding sex and promiscuity. A fresh spate of laws allowing authorities to scrutinize and criminalize sexual conduct passed in dozens of states. Many of these laws were specifically directed at sex workers, who were thought to indiscriminately (or even maliciously) spread infection. Scientific studies in the late 1980s proved that female sex workers were not a major vector in the spread of infection, but such laws remain on the books to this day.

That history leads us back to SESTA/FOSTA. Authorities argue that this law is about preventing trafficking, as would-be reformers have asserted for more than a century. In reality, the issue of trafficking is often brought up by those who want to harass sex workers. And as we have seen, the repression of safer means of sex work has led to greater danger and more male control. More control in the hands of pimps has, historically, led to more trafficking. The government’s repeated criminalization efforts over the past century have hardly resulted in a reduction in sex trafficking—often, the opposite.

SESTA/FOSTA is a predictable extension of laws already on the books outlawing prostitution; of stereotypes and stigma that inaccurately depict sex workers as purveyors of crime and infection; of policing that harasses (and sometimes abuses) sex workers while letting off their clients with a warning and a wink. Above all, SESTA/FOSTA exists because members of Congress refused to let sex workers drive conversations about how sex work should be regulated—just as the legislatures and international bodies of the past did not.

It is worth noting that today, unaids, the World Health Organization, Human Rights Watch, and Amnesty International all advocate the decriminalization of sex work. More important, peer-led sex workers organizations across the world do so as well. In 2013, for example, the Global Network of Sex Work Projects issued its Consensus Statement on Sex Work, Human Rights, and the Law, arguing for the right to associate and organize, the right to be protected by the law, the right to be free from violence and discrimination, the right to privacy and freedom from arbitrary interference, the right to health, the right to move and migrate, and the right to work and choose one’s employment.

Full decriminalization is different from legalization. Many popular examples of “legal” prostitution—as found in Germany, Amsterdam, Portugal, or Nevada—are systems that limit control by sex workers and vest authority in the hands of the state or exploitative men. In Nevada, for instance, where prostitution has been legal in some of the state’s counties since the 1970s, the sex trade is regulated in a punitive and counterproductive way. Prostitutes cannot legally work outside brothels—meaning they can’t operate independently—which forces them to labor under the control of brothel managers (often men). Brothel prostitutes often cannot choose their own doctors for routine STI screenings or, indeed, many of the conditions under which they labor, and they do not receive insurance or benefits from their employers because they are officially classified as independent contractors. Because of these regulations, most prostitution in Nevada occurs outside brothels—and thus illegally.

Allowing sex workers to control the conditions of their work—that is, to operate brothels themselves, choose their physicians, provide and receive benefits, and work outside brothels if they so choose—would be a step toward improving their lives. Authorities should consider the examples of the 20th century, as well as modern San Francisco, where in 1999 sex workers opened their own clinic to provide health care, education, and aid for current and former sex workers and their families. This clinic, the St. James Infirmary, remains open to this day. Another way to prevent trafficking is to eliminate the structural conditions under which it thrives by giving women greater access to sex education (and sex-positive education, which doesn’t stigmatize pleasure or overlook consent), reforming police practices, and boosting systems of financial and social support for marginalized women. Sex education can empower women and also make them more aware of exploitative and dangerous behaviors; giving police less power over the lives of sex workers can diminish abuse and predatory quid pro quos; fighting poverty and stigma can address the conditions under which trafficking thrives.

The country that has come the closest to an ideal system, in my eyes, is New Zealand. In the early 2000s, New Zealand’s legislature considered the Prostitution Reform Act, which legalized voluntary prostitution and recognized contracts between sex workers and their clients. After contentious debate, the legislature passed the bill in 2003 by a single vote. The lobbying of sex workers themselves, including the advocacy of the New Zealand Prostitutes’ Collective and Labour MP Georgina Beyer (a trans former sex worker), was critical to the bill’s passage.

In New Zealand, sex workers control their own working conditions: individuals can sell sex inside or outside brothels, on the streets, inside their homes, or with associates. Sex work is regulated like other businesses and subject to occupational safety and health regulations—but police involvement is relatively minimal. Sex workers have an absolute right to decline clients without providing a reason. Human trafficking is illegal, and those requiring a visa cannot legally travel to New Zealand to work in the industry.

The New Zealand model is not perfect, and sex work remains stigmatized and sometimes unsafe. Sex workers can face restrictions on advertising their services, and abuse by authorities remains a real concern. Nonetheless, it may indicate a path forward. Perhaps unique among legislatures in the modern world, the New Zealand parliament heard the voices of sex workers and heeded their calls as it was considering a new model of sex work.

American legislators would do well to study the outcomes of New Zealand’s decriminalization. Five years after the act was passed, a government review committee found that “the sex industry has not increased in size … and the Committee is confident that the vast majority of people involved in the sex industry are better off under the [Prostitution Reform Act] than they were previously.” Retrospective studies indicate that prostitution by those younger than 18 (which the act prohibited) has not increased. Between April 2017 and March 2018, the New Zealand government prosecuted three defendants for sex trafficking. By comparison, in fiscal year 2018, the FBI prosecuted 467 defendants.

Since SESTA/FOSTA became the law of the land, sex workers have reported that demand for their services has not changed—and that street-based sex work has increased. The legislation “has suddenly re-empowered this whole underclass of pimps and exploiters,” Pike Long, deputy director of the St. James Infirmary, told a San Francisco news station in February. As Savannah Sly, with the Sex Workers Outreach Project, testified to the Washington state Senate Labor & Commerce Committee in March, “What we’re seeing is an uptick in violence across the sex trade since the passing of these bills.”

Already, more than 20 individuals and organizations have come together under the umbrella of Decrim NY, a sex worker–led coalition pushing for decriminalization. Several New York state legislators have announced plans for a comprehensive bill that would decriminalize sex work; one of them, State Senator Julia Salazar, included decriminalization in her 2018 campaign platform. And 2020 presidential candidates are facing questions about sex workers’ rights.

As a historian, I have some hope for the future because for more than a century, sex workers have refused to silently submit to the paternalistic policies of the state—we cannot forget the marches, prison riots, pickets, spontaneous uprisings, and coordinated movements. The protests in the wake of SESTA/FOSTA’s passage are part of the legacy of these earlier acts of resistance. Such resistance will continue. If lawmakers truly want to eliminate trafficking, they must let sex workers drive the conversation, believe sex workers when they talk about their lives, and work to ameliorate the conditions under which poverty and bigotry thrive. Current legislation only stands in the way.