A performance last March of Anton Bruckner’s Eighth Symphony, by Christian Thielemann and the Vienna Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall, was very possibly the peak event of the New York season. And yet, when it ended, I discovered myself shouting my displeasure.

Bruckner’s Eighth lasts 80 minutes and is exhaled in a single breath. It invites—it demands—a pact with the audience. It is communal. It cannot be fairly experienced in a living room. On this occasion, Carnegie Hall had been sold out for weeks. The audience was a marvel—if not fully intergenerational (listeners under the age of 30 were scarce), at least strikingly international.

It took Thielemann barely a moment to secure perfect quiet: 2,790 souls in thrall. He navigated the great structure with monumental assurance. The last movement ends with a famous apocalyptic coda. Bruckner pauses for a long, capacious breath. Then he restarts his engines quietly, gradually, and with the unmistakable promise of a culminating paragraph. In a compositional tour de force both ingenious and inevitable, he proceeds to pile all the symphony’s themes atop one another. This achieved, he drives a refulgent final thrust. Thereafter, Thielemann and the musicians froze. And so did everybody else, save someone in the left balcony who broke the spell by bellowing “Bravo!” Thielemann reacted with visible consternation. But there was worse.

Not long after the performance began, the little lights had begun appearing, raised high. The hall’s ushers dutifully raced hither and yon, up and down aisles, gesturing frantically. And the cellphones were put away. Some clever listeners, however, realized that they could film the symphony’s iconic ending with impunity.

With the trembling onset of the coda, I had moved to the edge of my seat. I was in my preferred location—center balcony. As it happened, one of the offenders was seated directly in front of me. She held her phone high, blocking my field of vision with her bright miniature screen. The ovation was deafening, and that’s when a shouting match between us began. Reflecting on this experience, I discover that her behavior was less discourteous than it was selfish. As far as she was concerned, she was the only listener who mattered. The world of cellphones is both cause and effect of what some call “hyper-individualism.” I cannot think of a purer example than the woman who filmed Bruckner’s coda to take home as a memento.

When I posted my experience on my blog, the most interesting responses came from readers in London and Berlin. They said that an intrusion of this kind—not inadvertently failing to turn a cellphone off, but consciously flaunting it—was “unthinkable” in a British or German concert hall. And that is something to think about. It’s the same strain of personal entitlement that said “no” to Covid mask mandates. Its American lineage is potent.

And yet, my New York cellphone debacle came directly after an exemplary shared experience of music in live performance: two weeks’ worth of Dmitri Shostakovich in South Dakota, including the Leningrad Symphony in Sioux Falls and performances of the Eighth String Quartet at the University of South Dakota and South Dakota State. Perhaps all this manifested a benign Lutheran strain—a traditional receptivity to the arts that is respectful and communal. I’m certain it registered the sustained impact of Delta David Gier, the music director of the South Dakota Symphony, who in 2005 moved to Sioux Falls to raise a family there.

As is increasingly apparent, the arts in post-pandemic America are sharply declining. (I wrote about this crisis two years ago, in “Our Revels Now Are Ended,” published in these pages.) Diminishing audiences and funding resources will dictate fresh strategies. In these visits to Carnegie Hall and South Dakota, I learn twin lessons. One is about retaining contact with the cultural past—with traditions profoundly preserved and served. The other is about finding new ways to move forward, cognizant of changing times and circumstances. If classical music has a viable future in the United States, we will need to absorb both.

The present fraught American moment—an impasse that seems ever worse than before—is typically observed and discussed in terms of governmental and political dysfunction, of social decay, of religious decline. Barely mentioned, if at all, is that the arts are today in crisis in the United States—or that music, theater, literature, and the visual arts were once a binding factor, defining America and individual Americans.

So unnoticed are the American arts that a major American historian, Jill Lepore, can produce a wonderfully readable 900-page historical overview—These Truths: A History of the United States (2018)—without devoting so much as a sentence to the arts. No one could possibly dispute her emphasis on present-day issues and needs—the urgency of pondering American race relations and inequality. But it does not follow that there should be no consideration of Walt Whitman or Herman Melville, Emily Dickinson or William Faulkner, Charles Ives or George Gershwin, Duke Ellington or Billie Holiday. Classical music, opera, theater, jazz, and Hollywood are all absent. Could any history of Russia omit Tolstoy? Could a British historian overlook Shakespeare? Is there a Germany without Goethe?

Two years later, Robert D. Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett published The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again. It was accompanied by a new edition of Putnam’s best-selling Bowling Alone, subtitled The Collapse and Revival of American Community. The necessary topic at hand was the absence of “social capital” in today’s fragmented United States, as researched by a leading sociologist. To my amazement, Putnam did not invoke the arts as a potential source of social bonding and community. He did not even perceive the social significance of the arts during the Gilded Age, when New World institutions of culture enjoyed an astonishing early heyday.

In 1883, Mariana Van Rensselaer—America’s leading critic of architecture and a formidable arbiter of culture generally—wrote in Harper’s,

This our nineteenth century is commonly esteemed a prosaic, a material, an unimaginative age … blind to beauty and careless of ideals. … But leaving out of sight many minor facts which tell in the contrary direction, there is one great opposing fact of such importance that by itself alone it calls for at least a partial reversal of the verdict we pass upon ourselves as children of a nonartistic time. This fact is the place that music—most unpractical, most unprosaic, most ideal of the arts—has held in nineteenth-century [American] life.

In fact, the late Gilded Age charts the apex of classical music in America. Its central mission—which turned diffuse and subsidiary after World War I—was the creation of an American canon of symphonies, sonatas, and concertos. Its institutional embodiment was the concert orchestra—virtually an American invention, in contradistinction to the pit orchestras of the European opera house. Its prophet was the conductor Theodore Thomas, whose pioneering Thomas Orchestra plied the “Thomas Highway” north to south and coast to coast. Thomas preached: “A symphony orchestra shows the culture of the community, not opera.” Opera connoted theaters with balconies hosting rowdies and morally suspect companions. Orchestras connoted Beethoven: a moral lodestar. Thomas called his concerts “sermons in tones.” He became founding music director of the Chicago Orchestra—today the Chicago Symphony—in 1891.

Thomas is one of two individuals most responsible for implanting classical music in American soil. The other was Henry Higginson, the banker who invented, owned, and operated the Boston Symphony Orchestra beginning in 1881. Higginson was no Brahmin snob. As a music student in Vienna, he could not afford three meals a day. A trained musician, an impassioned music lover, he resolved to create a permanent orchestra for the city he had early made his home. He was practical, openhearted, widely experienced in many walks of life, rich in friendships, quickly susceptible to profound feeling. Of the slow variations capping the finale of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony, he wrote, “The gates of Heaven open, and we see the angels singing and reaching their hands to us with perfect welcome. No words are of any avail, and never does that passage of entire relief and joy come to me without tears—and I wait for it through life, and hear it, and wonder.”

The Boston Symphony’s first home was the drafty Music Hall. Higginson replaced it in 1900 with the acoustically superb Symphony Hall—the orchestra’s home to this day. Its functional New England plainness is democratic: there are no boxes. And Higginson from the start set aside 25-cent tickets for nonsubscribers. Symphony Hall’s sense of place, honoring Boston’s awareness of history and of its Puritan legacy, contributed to the fulfillment of Theodore Thomas’s credo: Boston’s symphony showed “the culture of the community.” It was—a distinction unknown today in the American arts—the city’s central, centralizing civic institution. Isabella Stewart Gardner, the Back Bay queen bee who was herself a reckonable force in the city’s musical life, sometimes turned up with a Boston Red Sox headband. Important local composers—George Whitefield Chadwick, Arthur Foote, Amy Beach—were Symphony Hall fixtures, both in the house and on the stage. When Artur Nikisch led Beethoven’s Fifth in a reading more flexibly Romantic than Bostonians were accustomed to, inflamed controversy in the daily press lasted nearly a month: Boston’s cultural pedigree was at stake.

Nikisch went on to become Germany’s preeminent symphonic conductor. During his four Boston seasons, he led 388 concerts. That is, he stayed put. Another Boston Symphony conductor who came and stayed put was Serge Koussevitzky, whose tenure lasted from 1924 to 1949. Rarely did anyone else lead the Boston Symphony during that quarter century. In Philadelphia, a world-famous orchestra emerged under the leadership of Leopold Stokowski, from 1912 to 1936. Like Koussevitzky, he was a civic fixture. He ceaselessly promoted new and unfamiliar works. He conducted everything, including young people’s concerts. Meanwhile, Koussevitzky realized his vision of a permanent American music center: the Tanglewood Festival, which he considered his most significant legacy.

Preponderantly, however, classical music in America was not about Stokowski’s relentless experimentation or Koussevitzky’s quest for the great American symphony. The defining American classical musician was the New York Philharmonic’s Arturo Toscanini, who recycled Germanic masterworks, retained Italian citizenship, and frequently shared his New York Philharmonic podium with guests. Notwithstanding fin-de-siècle expectations, notwithstanding the later efforts of Stokowski and Koussevitzky, classical music in the United States remained Eurocentric. Its New World roots remained stunted, nascent, predominantly shallow.

Today’s Boston Symphony music director is Andris Nelsons, who is also Kapellmeister of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra; during the 2023–24 season, he will conduct 34 of 66 subscription concerts in Boston and fewer than half of the orchestra’s summer concerts at Tanglewood. Today’s Philadelphia Orchestra music director is Yannick Nézet-Séguin, who is also music director of the Metropolitan Opera. This factor alone cancels Thomas’s prophecy. As Alex Ross, music critic of The New Yorker, once put it,

For a music director to carry off an ambitious project, you have to be there. You have to be on the scene, persuading people, interacting with them, listening to their ideas. Not just communicating your own. Building a sense of cooperation. You cannot do that as effectively if you’re flying in for two or three weeks, and another couple of weeks in the winter, and another two weeks in the spring. I find it a bit outrageous that music directors are so highly paid to begin with for one job—and then you find them holding a second or even a third position with exorbitant salaries in those places as well. This, of all things, is something the orchestra world should really be thinking about: drastically revising our idea of who a music director is, what their job entails.

Ross told me he had long considered visiting Sioux Falls to see for himself what Delta David Gier was up to—programming quantities of new music, regularly tackling big repertoire, linking to communities across the state. For Gustav Mahler’s Symphony of a Thousand, part of a complete symphony cycle dedicated to that composer, Gier had used a chorus from South Dakota State University packed with agriculture and engineering students. For Bach’s St. Matthew Passion (unabridged), Choir I was the South Dakota Symphony Chorus, Choir II the combined choruses of South Dakota State and the University of South Dakota—campuses an hour away from Sioux Falls in opposite directions. For Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman, the choristers were Mennonites from Freeman (population 1,300—“a singing community,” Gier says). Gier has programmed six other complete operas. He has given Peer Gynt with Grieg’s complete incidental music and actors. (“Though they’re descendants of Norwegians, very few people around here had read Ibsen’s play.”) Finally, last April, a major world premiere—of John Luther Adams’s 45-minute An Atlas of Deep Time—impelled Ross to fly to Sioux Falls. He wound up naming the concert one of the 10 “most notable performances,” nationally, in 2022: “There’s just a tremendous amount of caution, a tremendous amount of groupthink, in the orchestra world. So to see an orchestra really out on its own, forging its own identity, and bringing its audience along with it is just extremely impressive—even more impressive than I anticipated.”

South Dakota’s may plausibly be considered the most genuinely innovative, most inspirationally forward-looking professional orchestra in the United States. It is also the happiest professional orchestra I know, and the most engaged. Fulfilling Theodore Thomas’s credo, it “shows the culture of the community.”

Gier never intended to conduct in South Dakota. For many years, he was an associate conductor with the New York Philharmonic, handling young people’s concerts, covering for Kurt Masur and Lorin Maazel. When he landed the Sioux Falls job in 2004, he waited a year before moving there. “I looked at it as a steppingstone, but it didn’t happen,” he says. He was already 44 years old. Though it’s well known that conductors ripen slowly, the market has for some time favored young (and green) conductors as marketing assets. Today, women and African Americans have a decided edge in landing music directorships and guest engagements. And yet, for Gier it all worked out. “South Dakota was a wonderful surprise,” he says. “I was able to ascertain what people wanted. I was able to really accomplish something. I just never could have imagined it all.”

Early in his tenure, Gier proposed that the South Dakota Symphony initiate an annual Martin Luther King concert. He was taken aside and informed that, in South Dakota, racial bias targeted Native Americans. He next hosted a lunch for Lakota and Dakota leaders. “I went into that with all kinds of ideas about how we could collaborate,” he recalls. “But I was met with distrust—which in retrospect is not surprising. ‘What’s in it for you?’ ‘Who’s making money?’ A litany. It was my first lesson in learning to listen. At the end of that lunch, a man introduced himself and said, ‘You’re crazy. But I’d like to try to help.’ That was Barry LeBeau, an actor and lobbyist. I spent a couple of years making intermittent trips around the state with Barry introducing me to tribal elders and leaders.”

Gier arrived in Sioux Falls with the notion that “an orchestra should serve its unique community uniquely.” He wasn’t sure what that would look like—but he knew he had never seen it happen. His core conviction was that cultures could better be bridged through music than through conversation and debate. He encountered skepticism on all sides. His own musicians questioned whether they should be “enforcing white culture on Native Americans.” The turning point, Gier says, was a snowy evening on the Pine Ridge Reservation in 2005:

It was basically a jam session between our string quartet and woodwind quintet and a drumming group, the New Porcupine Singers. Everyone was a little nervous. We started by just playing music for one another, and people talking about what the music meant to them. Then after an hour or so, the Keeper of the Drum for the Porcupine Singers, Melvin Young Bear, stood up and said, “We sing the old songs. We’re not a pow-wow group. We hope to pass on our traditions to the next generation.” And I thought, bingo, that’s exactly what we do. It was a mission we could share.

My own introduction to the Lakota Music Project came in 2016. As director of an NEH-funded concert initiative, Music Unwound, I found myself collaborating with Gier on one of many “Dvořák and America” festivals. Antonín Dvořák, who directed New York City’s National Conservatory of Music from 1892 to 1895, had prophesied a future American classical music rooted in twin sources: Black America and Native America. He drew inspiration from his interactions with the Kickapoo Medicine Show—Native American entertainers who sang and danced—during a summer in Iowa. And he was riveted by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha (1855)—in the 1890s still the most-read, best-known American literary work. I imagined that this story, retold in South Dakota with the participation of Native Americans, would prove fruitful. Gier agreed—but with a degree of foreknowledge I had barely glimpsed.

A crucial early ingredient in the Lakota Music Project was the permanent engagement of a prominent scholar of Lakota music and culture, Ronnie Thiesz. (A rare initiative: though museums have scholars on staff who initiate research, American orchestras have failed to intersect with the scholarly community.) Now retired, Thiesz is an Austrian who after earning a PhD in ethnomusicology at NYU took a job teaching at Black Hills State College in Spearfish—and never looked back. He also became the only non-Native member of the Porcupine Singers. And Thiesz, I was apprised by Gier, viewed Longfellow as a merchandizer of myth—that of the “noble savage”—who confused the Indian legends he repackaged. What is more, Thiesz mistrusted Dvořák’s efforts to adapt Native American sources. This impasse became my introduction to Gier’s methodology: three months of conversation and negotiation. I discovered in Ronnie Thiesz the same personal qualities I would discover in the musicians Emanuel Black Bear and Bryan Akipa: gravitas, deliberation, and patience.

Early on, Chris Eagle Hawk, an honored elder of the Oglala Lakota Tribe, took me aside to share an axiom. One should listen with one’s heart, he said, and only later process words with one’s brain. In the meantime, one’s mouth should remain shut. Though (as Chris had noticed) this is a lesson I have never learned, I shut my mouth sufficiently that a singular South Dakota Symphony Dvořák program emerged. The second half—something I have produced innumerable times—combined the New World Symphony with a “visual presentation” extrapolating its American accent: African-American and Native-American imagery, as well as iconic paintings of the American West. The 75-minute first half, unique to South Dakota, featured the Creekside Singers of the Pine Ridge Reservation in a symphonic composition by the Native American composer Brent Michael Davids. Thiesz contributed a mini-tutorial on the structure and vocal techniques of Lakota song. Chris Eagle Hawk eloquently described the role of music in Lakota culture and the sanctity of the Black Hills. Gier contrasted Longfellow’s “noble savage” trope with such 20th-century Indianist kitsch as Victor Herbert’s “Dagger Dance” (which I remember hearing as a child via cartoon commercials for Hamm’s beer).

Following two performances in Sioux Falls, we took the whole show to Sisseton; half of its 2,500 residents are Native Americans from the Sisseton Wahpeton Reservation. Sisseton produced the most eclectic audience I have ever encountered at a symphonic concert. Both the very young and the very old were well represented, as was the local Dakota population. Dvořák’s sadness of the prairie instantly evoked the wide horizons directly at hand. Not the least memorable aspect of this event, for me, was the three-hour bus ride. I had been on buses with orchestral musicians before; they were workers doing a job. But here, 50 members of the South Dakota Symphony were pursuing a mission.

The outstanding principal oboist of the South Dakota Symphony since 2003, Jeffrey Paul, also happens to be an outstanding composer. When he composed Wind on Clear Lake (2013), Paul began in a cabin on Clear Lake itself, listening to the wind through the cottonwoods. He discovered music there—a quasi-pentatonic strain he sensed he and his colleagues could share with the Lakota flutist Bryan Akipa. A core participant in the Lakota Music Project since 2013 and a National Heritage Fellow, Akipa is credited with reviving an ancestral Lakota musical tradition. He plays wooden flutes, with five or six holes, that he carves himself. The pungency of Wind on Clear Lake arises from the slight disparity between the wavering pitches of Akipa’s instrument and the notes being played by Western strings and winds. When I asked them how they experienced preparing this score together, Akipa and the South Dakota Symphony players all used the same adjective. They said they found it “humbling.”

Week-long “composition academies” are another component of the Lakota Music Project. Orchestra members visit Indian reservations to collaborate with grade-school students on chamber pieces embedding the students’ compositional suggestions. The South Dakota Symphony’s principal second violinist since 1998, Magdalena Modzelewska, performs the resulting music with the Dakota String Quartet. “It’s really stunning, what’s happening with those kids, the light that we see on their faces,” she says. “For quite a few, it’s changed their lives. They were on the verge of something awful—and it pulled them through. Some have gone on to college to study music—where it was not even a consideration before.”

Of the Lakota Music Project experience, Modzelewska says, “In Indian culture we’ve found such peace and goodwill. It’s truly remarkable how similar our musical goals are. We get to share something sublime.”

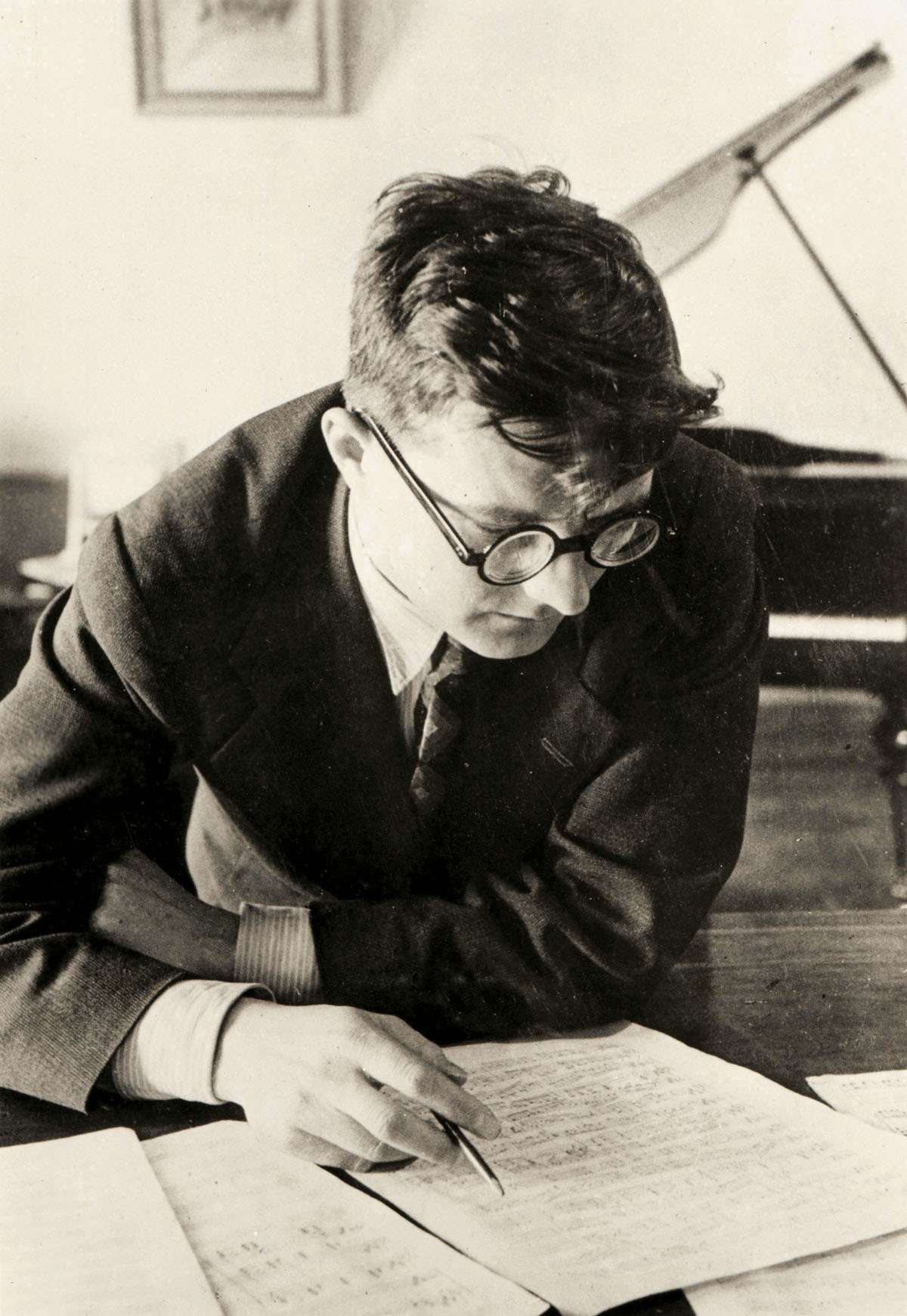

Dmitri Shostakovich in the early 1940s. In 1941, he bore witness to the Siege of Leningrad with his searing and defiant Seventh Symphony. (Everett Collection Historical/Alamy)

In the seasons following “Dvořák and America,” the South Dakota Symphony mounted two more NEH-funded Music Unwound festivals. The central purpose of “Copland and Mexico” was to showcase not Aaron Copland (whose name sold tickets) but his Mexican contemporary Silvestre Revueltas, a galvanizing political artist whose concert works and film scores parallel the murals of Diego Rivera. The central purpose of “American Roots” was to showcase America’s preeminent symphonist, Charles Ives—with Dvořák and George Gershwin driving the box office. These were scripted, multimedia projects I had produced elsewhere. But only in South Dakota was the music director a proactive creative force. For “Copland and Mexico,” Gier interpolated—as an interruption with placards, stopping the concert in its tracks—a re-creation of Copland’s grilling by Senator Joseph McCarthy in May 1953, during the height of the Red Scare. For “American Roots,” Gier interpolated paintings by South Dakota’s foremost Native American artist, Oscar Howe. All this formed the backdrop for the Shostakovich performances last February and March (in which I again took part as an artistic consultant).

Mindful that “an orchestra serves its unique community uniquely,” Gier chose the Leningrad Symphony partly for its programmatic content. Shostakovich wrote symphonies musically more distinguished, but the story of the Seventh is unique. It is an exigent product of the Siege of Leningrad, when Hitler’s army surrounded a city of six million people for 872 days with the intention of starving its inhabitants while bombarding them from the air. One and a half million Russian soldiers and civilians lost their lives. The snowy streets were littered with corpses. Shostakovich, whose genius was to bear witness, composed a symphony for the city he called home. Miraculously, all 80 minutes of it were actually performed there, 11 months into the siege. Only 15 members of the Leningrad Radio Symphony were alive and able to play. Other instrumentalists were brought in from Soviet Army bands. Special rations were procured. The ovation was fervent and stoic—it was Leningrad applauding its own resilience. People left feeling strangely elated.

Gier’s fundamental consideration was how to maximize impact. He decided on a scripted preamble with musical examples. Early on, he shared the project with the University of South Dakota and South Dakota State. Both agreed to host lectures and an ancillary concert featuring the Dakota String Quartet in Shostakovich’s most autobiographical composition, his agonizing Eighth Quartet of 1960. Ultimately, the preamble took the form of a 40-minute “dramatic interlude” beginning with music from Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk—the lascivious bedroom scene that in 1936 so aroused Stalin’s ire that the composer was denounced in Pravda. Gier narrated the subsequent vicissitudes of Shostakovich’s relationship with the state. He explored the ambiguous ending of Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony, an ostensible act of contrition that may also be read as a musical act of defiance. He evoked the siege of Leningrad. He explored the Seventh Symphony. He summarized:

Shostakovich learned three things. The first was that he could convey extra-musical messages in a wordless symphony. The second was that—because music is less explicit than words—these messages could actually be subversive, connecting with needs and beliefs that could not safely be spoken. The third was that he could become a true “people’s artist”—not by serving an autocratic state, but by serving more profound human needs, groping for a common humanity more fundamental than any ideology.

The quartet concerts at the two universities were also contextualized. Shostakovich composed the Eighth Quartet after joining the Communist Party. Though this painful decision was denounced even within the U.S.S.R., it enabled Shostakovich to exert more leverage in the artistic community—a complex tradeoff. And yet, he was reportedly suicidal. All of this, and more, was shared with rapt student audiences. David Reynolds, the director of the School of Performing Arts and professor of music at South Dakota State University, vigorously supports collaboration with the South Dakota Symphony—not least because it includes music and music appreciation students as well as global studies and political science students. He bused dozens of students to Sioux Falls for the Leningrad Symphony performance; many took part in an hour-long postconcert conversation there.

Reflecting on dropping enrollments in the humanities—at South Dakota State and just about everywhere else—Reynolds says,

I realize that in some high school curricula today the story of World War II may be only a week. I think that finding a way to use the performing arts to bring this kind of story to life is a wonderful opportunity to touch students who are growing up with social media and other nontraditional resources. Students in our music appreciation classes—those are the folks that one of these days will be bank presidents, school board presidents, and will decide the role of the arts in public and private schools. It’s very important for them to have experiences just like this one—Shostakovich and the Siege of Leningrad. To get them thinking that life would be incomplete without the arts being a part of it.

For Mark Bertrand, the pastor of the Grace Presbyterian Church in Sioux Falls, Shostakovich’s Leningrad Symphony evoked the resilience of Ukrainian resistance to Russia’s invading army in 2022–23. Bertrand also found himself thinking about the role of culture in a nation’s life:

It’s striking that as the symphony was being composed, Shostakovich was updating people in real time about his progress. They were looking forward to this happening. And it can’t be the case that this besieged population was just seeking some entertainment to get their thoughts off their everyday reality. I tried to imagine us today feeling a similar kind of anticipation for an artistic statement. We don’t value things the way they did. It really gets you thinking about how different their values must have been. You know, I would say that I’m a cynical person by nature. David [Gier] is constantly challenging that cynicism and renewing my confidence in the meaning of music, in the meaning of the arts. I feel that I’ve been elevated through this experience as much as anyone.

As Shostakovich’s symphony began its slow, inexorable ascent toward a final climax, Bertrand found himself thinking about words quoted earlier in the evening. The Russians not only broadcast the Leningrad Symphony throughout the Soviet Union. They managed to broadcast it via loudspeakers to the Nazi troops blockading Leningrad. After the war, a German soldier testified, “It had a slow but powerful effect on us. The realization began to dawn that we would never take Leningrad. We began to see that there was something stronger than starvation, fear and weather—the will to remain human.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9PJXMkmGsY

All this preceded Bruckner’s Eighth at Carnegie Hall by a mere week. Notwithstanding the Carnegie cellphones (an accessory wholly absent in South Dakota), the South Dakota Symphony and Vienna Philharmonic in concert complemented more than contradicted each other. At the heart of both performances were musical experiences both communal and rooted. In Sioux Falls, the roots were American, nurtured for two decades by Delta David Gier. At Carnegie, the roots were Viennese, nurtured for more than two centuries starting with Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert.

The Vienna Philharmonic premiered four of Bruckner’s nine symphonies. Bruckner’s occasional rusticity—his fond allusions to folk dance—is part of the orchestra’s bloodline. Bruckner’s organ sonorities align with the smooth, creamy textures that remain a Vienna Philharmonic signature. At Carnegie Hall, Thielemann’s encore was Music of the Spheres by Josef Strauss; the orchestra kicked the second beat of the waltz rhythms with singular authenticity.

A famous recording of Bruckner’s Eighth was made in live performance by Wilhelm Furtwängler on April 10, 1954. The orchestra was the Vienna Philharmonic. Furtwängler’s version is very different from Thielemann’s today. From the start, the descending woodwind phrase responding to the strings’ main theme is streaked with pain. In the Adagio, which Bruckner asks be rendered “tenderly,” the presiding mood is one of heartbreak. It was Furtwängler’s genius—setting him apart from all other conductors of his generation—to channel the moment. In ways not so different from Shostakovich’s contemporaneous compositions, his wartime performances narrate calamitous tragedies—which his postwar performances (he died in 1954) profoundly remember.

Thielemann reveres Furtwängler but is too sophisticated to imitate. He finds scant Weltschmerz in Bruckner’s Eighth. But at Carnegie Hall, he did pull off a grand Furtwängler rubato—a species of climax virtually extinct today. A classic instance crowns Furtwängler’s 1954 Vienna Philharmonic recording of Wagner’s Lohengrin Prelude. As I once wrote in Understanding Toscanini (1987), distinguishing Verdi’s (and Toscanini’s) accelerating climaxes from the Wagnerian school of interpretation Furtwängler perpetuated,

Furtwängler’s climaxes pre-empt repose and lead to exhaustion. Their slow, weighted pulse might be likened to that of a pendulum swinging with greater force as it spans ever longer arcs. Their visceral impact bears some relation to the Hollywood convention of shooting moments of crisis or ecstasy in slow motion. Inner turmoil produces a sensation of temporal dislocation. Time “slows down,” even “stands still.” In the Prelude to Lohengrin, Furtwängler’s slow-motion climax seems to exist outside time.

In Bruckner’s Eighth, the climax of the half-hour Adagio is punctuated by two cymbal crashes. Here, Furtwängler eschews a time-stopping deceleration. But Thielemann does not. On Thielemann’s recent Sony recording, the effect is labored. At Carnegie, the effect was tremendous. In fact, a climax this extreme is a risk. It cannot be precisely conducted. It must be felt by a hundred players, and the feeling is wholly interior. It relies on instinct and tradition.

Where all this leads, today, is an interesting question that connects to the American failure to produce an adequate classical music canon. The quintessential American orchestra was Leopold Stokowski’s in Philadelphia; it produced a seamless, kaleidoscopic, even cinematic New World sound that was sui generis, and that served sui generis New World readings of Old World masterworks. That many members of other major American orchestras retained German, French, or Italian musical roots was decisive. Here, the most striking example was the astounding Metropolitan Opera orchestra as heard on broadcasts from the 1930s and ’40s. The players were predominantly Italian. Some had played in the Met pit under Toscanini, even Mahler. They intimately knew the operas. Two conductors of genius presided: Ettore Panizza, leading the company’s Italian wing, and Artur Bodanzky, in charge of Wagner. Both invariably produced a powder-keg intensity of expression and commitment (try Otello from February 12, 1938; or Brunnhilde’s Awakening from Siegfried from January 30, 1937). Today’s Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, in comparison, is uprooted: faceless and tame. And the Stokowski lava flow is not even a memory.

And so, South Dakota becomes a manifesto. I would never propose that the Vienna Philharmonic’s Bruckner performances add a 40-minute preamble. The Berlin Philharmonic performing Beethoven, the Mariinsky Orchestra’s peerless Shostakovich performances under Valery Gergiev are self-sufficient. But if you were to ask me whether the New York Philharmonic should perform the Leningrad Symphony sans commentary of any kind, I would certainly opine: those times are past.

At South Dakota State University, every student with whom I spoke about the Leningrad Symphony performance mentioned the 40-minute preamble as a crucial ingredient. Even in the case of undergraduate Austin Teas, whose “favorite symphony” was already Shostakovich’s Seventh, contextualization “elevated the experience.” He adds, “And that could be said about just about any symphonic work, in my opinion. Context is essential to reaching a broader audience.” A trombonist, Teas hopes to pursue music professionally. He follows the South Dakota Symphony’s Lakota Music Project on social media. During his senior year of high school, he played in the South Dakota Symphony Youth Symphony—and joined the parent orchestra for a young people’s concert performance of excerpts from the Mussorgsky-Ravel Pictures at an Exhibition. “It was a life-changing experience. I decided: I want to do this.”

At the University of South Dakota, Markus Klassen, who studies both piano and voice, considered an ancillary lecture on Shostakovich “as important” as hearing the Dakota Quartet perform the Eighth Quartet. “Being able to ask questions in real time made the performance come alive in a new way,” he told me. “I also think that contextualizing the quartet with commentary and musical examples actually influenced the performers. I think we should have a little bit of that at almost every concert … TikTok and social media, the inundation of easy music—it’s really damaged the attention span.” Klassen calls contextualizing the music a remedial strategy “hidden in plain sight.”

My own 26-year-old daughter watched the Leningrad Symphony performance via livestream. When it was over, she phoned me from New York to say how she wished that her friends could experience “concerts like that.” And there is another overdue responsibility. The standard narrative for American classical music—the one initiated and sustained in the postwar writings of Aaron Copland and Virgil Thomson—is defunct. Looking back, we can readily discern that it was a modernist narrative, prioritizing clarity and other “neoclassical” virtues, shunning the vernacular, cleansed of what Emerson memorably cherished as “mud and scum.” Accordingly, it denied the significance of music composed before World War I. This restriction squandered the Black musical mother lode once extolled by Dvořák and W. E. B. Du Bois. It marginalized our foremost classical music geniuses—Ives and Gershwin—as gifted dilettantes. It ignored the persistence of interwar Black classical music. In Dvorak’s Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Black Classical Music (2022), I propose a more inclusive “new paradigm” in which Ives and Gershwin are twin pillars. It is not enough to program Black composers in a rush to catch up. That effort, to date, has been scattershot. (The most formidable interwar symphony by a Black composer is surely the one by William Levi Dawson, not any of the four by the much-performed Florence Price.) It overlooks a story that deserves to be told in full.

Museums, privileging scholarship, diligently curate the American past. Here again the South Dakota Symphony shines a beacon light. Gier conducts Ives alongside Gershwin. Beyond the standard narrative, he has programmed pieces others overlook: Dvořák’s American Suite (a New World picture book postdating the New World Symphony), Silvestre Revueltas’s Redes (a landmark score for a film that was itself an iconic product of the Mexican Revolution), and Lou Harrison’s Piano Concerto (arguably the most formidable concerto by an American). Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony is high on his to-do list.

Violinist Magdalena Modzelewska told me, “Ours is a very special orchestra—and I have felt this for a long time.” She recalls a Harvard University study of “job satisfaction” that ranked orchestral musicians on a bottom rung. “What we feel here is something different—gratitude and friendship.” The orchestra’s board includes musicians as voting members. Very unusually, the musicians are not unionized—and do not seem to identify as a sectarian institutional component. Gier adds, “We’re very focused on our musicians and their satisfaction. They need to know how much they’re valued. Including them on the board is a game changer—they see how hard our board members work to fund them.”

As of this writing, New York City’s Public Theatre has announced that it will lay off 19 percent of its staff. The Brooklyn Academy of Music will reduce its staff by 13 percent. We will be reading about similar arts cutbacks elsewhere. Cycles of “emergency” Covid arts funding by Congress have come and gone with nothing to take their place. The usual belt tightening will not suffice—and nowhere more than in the symphonic sector.

Quite obviously, mine are inconvenient opinions. You will not find them emphasized at meetings and workshops of the League of American Orchestras. They do not mesh with prevalent norms for administrative staffing. Orchestras lack resources to adequately scour and contextualize the American musical past. Conductors lack the skill, the time, or the interest to fashion the teaching tools deployed by Delta David Gier—or by Leonard Bernstein decades before him. For many of our larger orchestras, shrinking audiences will logically dictate fewer concerts. And new audiences, generally, will present new needs.

Five months ago, the NEH funded a fourth installment of Music Unwound, supporting thematic festivals curating the American musical experience. The concerts will elaborately contextualize the repertoire at hand. All six participating orchestras, including the South Dakota Symphony, will partner with universities. Unbeknownst to many in the American orchestral community, a new moment is upon us: new templates for format and repertoire, templates tangible yet mainly dormant. They have in fact been awaiting our attention for quite some time.