Mind Fixers: Psychiatry’s Troubled Search for the Biology of Mental Illness by Anne Harrington; Norton, 384 pp., $27.95

Psychiatry today is in crisis. By some reckonings, mental illness is more prevalent than ever—yet the effectiveness rates of most treatments are no higher than they were 40 years ago. The profession is riven, as ever, by internecine clashes. The field’s guiding text, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, its bible since 1952, has been officially abandoned by the National Institute of Mental Health; the DSM’s most recent edition, the fifth, was bitterly denounced by the editor of the fourth. Most of psychiatry’s “cutting-edge” treatments date to the 1950s—and in some cases the 1930s. Even its basic terminology seems to be unraveling: Is “major depression” clinically distinguishable from “bipolar disorder”? From “generalized anxiety disorder”?

Underlying these are more fundamental questions. Are disorders like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder psychological problems, what practitioners since Sigmund Freud and Adolf Meyer have called “problems of living” or “failures to adjust,” and therefore properly treated via psychodynamic means—talk therapy and the like? Or are they medical problems—rooted in genetics and physiology, like cancer or strep throat—and therefore best ministered to biologically, via targeting the brain with drugs or shock therapy? Or, as critics like Thomas Szasz and R. D. Laing have argued, is the entire edifice of psychiatric disease a manufactured construct designed to maintain social control, invalidating certain forms of dissent and alternative modes of perception as the product of “mental illness”? Or is psychiatric illness a confection of Big Pharma marketing departments, with disease categories proliferating and inflating beyond reason in order to enlarge the reservoir of potential customers?

In Mind Fixers, Anne Harrington, a professor of the history of science at Harvard, explores these entangled questions, primarily via a narrative account of, as her subtitle has it, “psychiatry’s troubled search for the biology of mental illness.” Though the basic story Harrington tells is familiar—versions of it having been rendered in dozens of recent accounts of the history of psychopharmacology—her history is premised, bracingly, on the notion that psychiatry has steered itself into a dispiriting cul-de-sac where it has spent decades driving in circles.

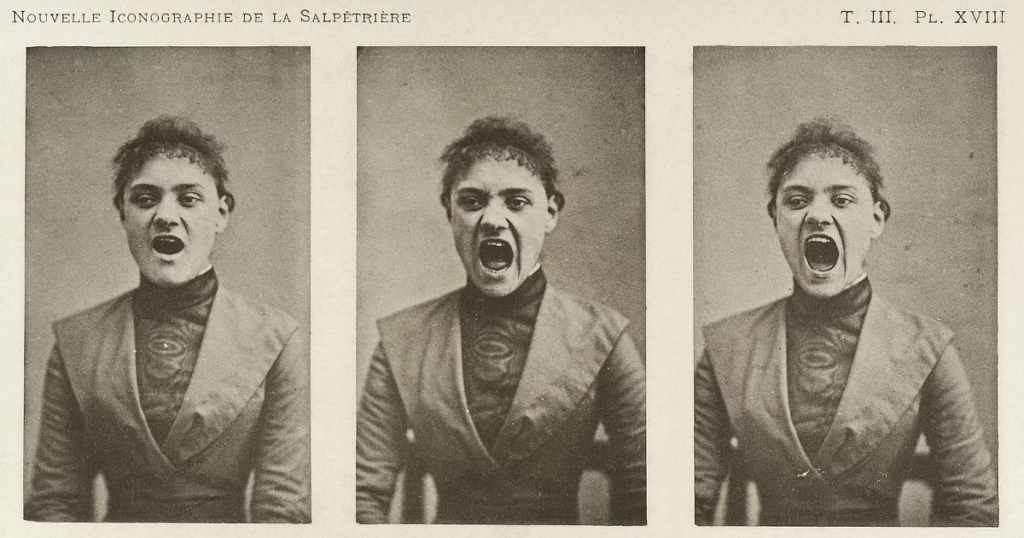

Psychiatry’s record is blemished by some remarkable failures. For starters, there were the dubious theories of hysteria promoted by the 19th-century French psychiatrist Jean-Martin Charcot and his disciple Freud. In the early 20th century, clinicians such as Henry Cotton, the medical director at the New Jersey State Hospital at Trenton, believed they could cure schizophrenics by performing colonic irrigations or surgically removing infected organs. (Up to 30 percent of Cotton’s patients died from such procedures.) Midcentury witnessed the field’s dark foray into lobotomy: in 1949, the Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for pioneering brain surgery as a treatment for mental illness; in 1952, Walter Freeman, a psychiatrist at George Washington University, embarked on “Operation Icepick,” traveling across the country to perform transorbital lobotomies in state mental hospitals.

Psychiatry’s sometimes tragic ineptitude at treating mental illness has been matched at times by a comic inability to diagnose it. In 1973, as Harrington recounts, a psychologist named David L. Rosenhan sent eight people with no history of mental illness into psychiatric hospitals, where they pretended to hear voices. All eight were wrongly diagnosed with either manic depression or schizophrenia and admitted for treatment. Once hospitalized, these patients started acting normal, but it took between nine and 52 days for them to be declared “in remission” and released. The staff of another hospital got wind of Rosenhan’s study and dared him to try and trick them in the same way. He accepted the challenge, and the hospital staff subsequently identified 41 fake patients—wrongly, as it turned out, since Rosenhan didn’t wind up sending anyone; all of the patients identified were real ones.

Subsequent research found that when two psychiatrists independently examined the same patient, they disagreed on the diagnosis nearly 70 percent of the time. How can research advance, or treatment protocols develop, when the field can’t agree on what’s being researched and treated?

One constant throughout Harrington’s history is psychiatry’s ongoing quest to try and put itself on reputable biomedical footing, to lend empirical respectability to a squishy and uncertain “science,” and “to assert guild privilege” against the onslaught of nurses, social workers, and psychologists who would tread on its turf. She lambastes a myth long promulgated by psychiatrists themselves: the idea that in the 1980s, after a half century wandering in the Freudian “wasteland,” the biological psychiatrists—armed with new discoveries from neuroscience, genetics, and psychopharmacology—wrested control of the field and placed it back atop its proper foundation in medical science, ending the psychoanalytic wrong turn. “It was a simple explanatory story, one with clear heroes and villains, and above all a satisfyingly happy ending,” Harrington writes. “The only trouble with this story is that it is wrong—not just slightly wrong but wrong in every particular.” The so-called biological revolution, she goes on to write, “overreached, overpromised, overdiagnosed, overmedicated, and compromised its principles,” leading to science and to patient outcomes that were just as bad as anything the Freudians had come up with. In Harrington’s telling, psychiatry can at times seem a mere pseudoscience, lodged somewhere between phrenology and chiropractic on the scale of scientific repute.

What does Harrington think the profession can do to save itself? First, psychiatrists should restrict themselves to dealing with the most serious forms of mental illness—like schizophrenia and other forms of psychosis—while leaving to other species of therapist the care of the “worried well.” Second, psychiatrists should at once be more modest in their claims and more ambitious in their search for the biomedical bases of mental disease. Third, the field should “commit to an ongoing dialogue with the scholarly world of the social sciences and even the humanities.”

Harrington’s historian’s-eye view of psychiatry is perhaps even darker than my own patient’s eye-view. (I have suffered from anxiety and depression for decades, and have tried with varying degrees of success many forms of treatment.) But my sense—perhaps motivated more by the need for hope than the presence of evidence—is that the prospect of more effective treatments lies at least theoretically on the horizon, if not even closer at hand. New clinical evidence piles up suggesting that various forms of mindfulness, as well as a widely used technique called Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, can be reasonably effective treatments for depression, anxiety, OCD, and other disorders. Meanwhile, experiments with ketamine, a club drug, and psychedelics like LSD suggest these old drugs may have promise as treatment for the suicidally depressed, while research into the neuroscience and genetics of mental illness is breaking new ground that might one day yield new, more effective medications.

Or maybe this is all just the latest spin on the psychiatry merry-go-round, and we will soon end up, yet again, back where we started.