One of the first things I noticed inside Billiam Jeans—a small Greenville, South Carolina, atelier that I visited a few years ago—was the row of antique sewing machines carefully arranged on a window ledge. The half-dozen people working inside happened to be seated at contemporary sewing machines, but the array of prewar counterparts was no mere window dressing.

Bill Mitchell founded the company, which sells its high-end denim at boutiques both here and abroad. A svelte, bearded twentysomething, he pointed to a first-generation Union Special 43200G hemming machine, or “edge locker.” Stout and brimming with thread, it looked like something you’d find in the dusty corner of a provincial industrial history museum. Mitchell told me that he’d purchased it from a seller in Thailand, at a cost more appropriate for an automobile.

What the 43200G does that most modern machines cannot is produce a distinctive chain stitch, a series of tight interlocking loops of thread on the underside of the hem. Over time and with washing, Mitchell said, the hem will begin to develop a prized “roping” effect, a kind of subtle spiral that has become de rigueur among makers of premium denim. Mitchell said his Union Special machine radiates an almost fetishistic power, with customers in thrall to the “idea that we care enough to go back into history and preserve the old-school way of doing it.” The scarcity of the machines, meanwhile, makes clients “feel they’re getting something they can’t get in other places.” Similarly, the use of selvedge denim, which is made on specific types of short-width looms—a once-common technique that has largely vanished—has come to be synonymous with quality.

This kind of intense focus on questions of authenticity and provenance, with use of a language foreign to the uninitiated, has long been the purview of the art or wine connoisseur, who confers the approval sought by anxious consumers and is valued for an unerring eye or palate. Now, however, the mantle of connoisseurship extends to any number of everyday things, like blue jeans, toothpicks, pickles, and pencils. Call it the connoisseurship of everything—a state where it becomes difficult to disentangle one’s love for objects from the pleasure that comes with the mastery of knowledge about those objects.

On one hand, it makes sense: Why should we drink anodyne brew, eat insipid foods, wear poorly designed clothes made in distant factories using questionable means, when closer examination, an almost obsessive attention to detail, can lead to better, more satisfying purchases? On the other hand, there is something exhausting, almost soul-draining about this constant, questing game of having the best possible exemplar of a thing, of having to learn (or pretending to learn) another set of tasting notes, consumption rules, gradations of quality. Must coffee always be single origin, come embellished with a story, be crafted by the latest, truest method? Why can’t coffee ever just be coffee?

The term connoisseur—from the Old French connoistre, “to know”—surfaced in earnest in the early 18th century, largely in the context of appreciating and validating paintings. For Bendor Grosvenor—the art dealer, historian, and cast member of the BBC’s Fake or Fortune?—the connoisseur was needed for one important task: “very simply, the ability to recognize the hand of an artist in a painting.”

But from the start, academic rigor in the field was clouded by connotations of snobbery and class. Jonathan Richardson’s Two Discourses (1719) first laid out the qualifications and proper work of the connoisseur, then emphasized how appropriate the “science” of connoisseurship was for a “gentleman.” Here the line between technical prowess and a larger sense of overall good taste was blurred, and eventually connoisseurship became synonymous with elitism. “Part of the problem of being able to say this is a Rubens or a Van Dyck,” Grosvenor tells me, “is being able to explain it in words”—words that can often seem exotic, distancing, indeed elitist. Perhaps because of the art world’s affiliation with the wealthy, this expert terminology was often held in suspicion.

It could also be seen as antidemocratic. As Alexis de Tocqueville observed in Democracy in America, “Equality begets in man the desire of judging for himself.” But there is a difference, Grosvenor says, between knowing what something is and thinking something is good. “There’s a tendency these days to popularize people’s response to art—your response to that work of art is as good as mine,” he says. “And it is—if we’re only judging whether we like it or not. But if we’re judging whether it’s by Rembrandt, you have to go ask the expert.”

A sort of paradox lies at the heart of the idea of democratized connoisseurship. Over time, as the rising middle class increasingly acquired the means to purchase things once restricted to the aristocratic elite, there was a rising pressure to have authority in any number of spheres—like wine, once a rather undistinguished drink. “In democracies where the differences between citizens are never very great,” Tocqueville wrote, “numerous artificial and arbitrary distinctions are invented.” And so we make the distinctions ever finer, the knowledge more obscure, the language more performative, the search for authenticity that much more charged. The trend has found its apotheosis in the current all-access age of social media, in which a bowl of Japanese ramen, for example, once a working-class street food, is elevated into an object of intense attention. One cannot simply eat ramen; one needs to eat ramen made to the exactingly correct specifications in just the right obscure place, and then post a photograph to Instagram.

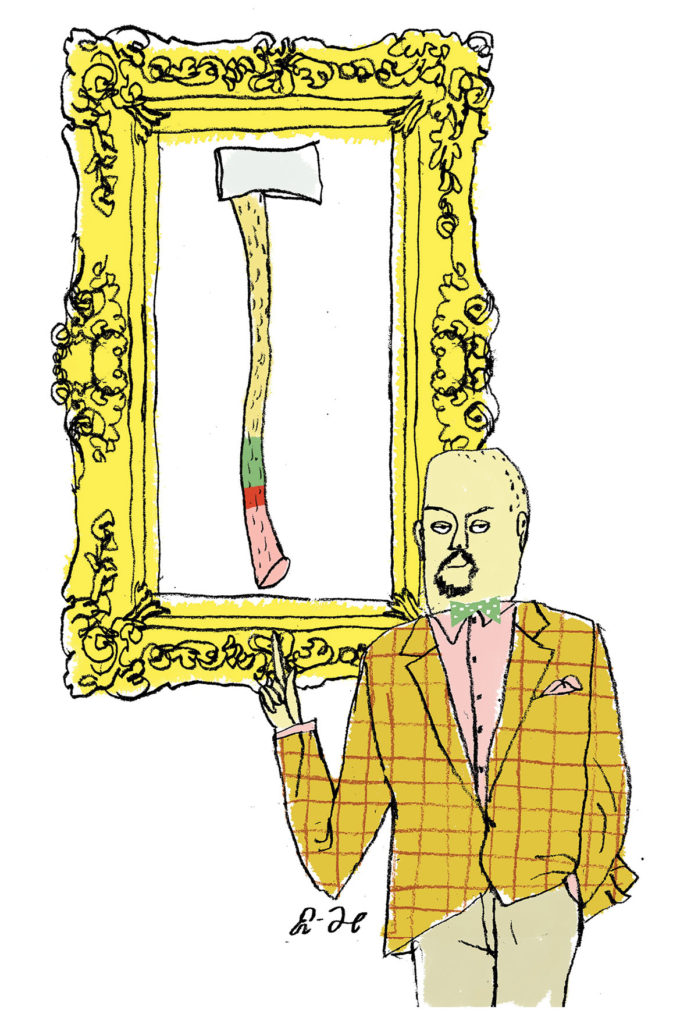

I am not in the market for an ax, but if I were, I would no doubt be tempted by a Best Made ax, produced by the eponymous New York–based company, which ceased production in October 2020. (You can still purchase Best Made axes from the Duluth Trading Company.) Best Made advertised axes from “American-made 5160 alloy steel … hardened to a Rockwell hardness of 54–56 HRC,” with a “straight-grain, premium hickory” handle “that originates in Appalachia.” Best Made axes have been displayed in such tony enclaves as the Saatchi Gallery, but I suspect that they are used less as tree fellers than as drop-forged signals of the buyer’s aesthetics. Hardly anyone swings an ax as labor, after all—lumberjacks these days use machines. When things become unnecessary, they can become art. And what so many of these products tap into is a sense of some lost craft or tradition—and a redemptive path to the “authentic.” Best Made’s axes certainly tick what I presume are all the right connoisseurial boxes. A Rockwell hardness of 54–56—that’s great! But wait, what is Rockwell hardness, and where does 54–56 sit on the Rockwell scale? Best Made virtually summons a world of discerning ax lovers into being, earnest and sturdy gents sitting in the woods comparing Rockwell hardnesses and the straightness of wood grain like they were sipping fine whiskey.

Lurking behind all of this is an actual crisis of authenticity. Restaurants have been accused of serving products falsely labeled “farm to table” (“farm to fable,” as one wag had it). Large producers of spirits have been sued for misrepresenting terms like “handcrafted.” Brooklyn’s feted chocolate makers The Mast Brothers, meanwhile, were accused in 2015, in a lengthy, much-commented-upon article by a Dallas food blogger who goes simply by “Scott,” of remelting “industrial couverture” and billing it as a “bean-to-bar” product. How did the blogger (among others) make this judgment? Largely by taste and texture. In an age of democratized connoisseurship, it seems, we still need actual connoisseurs.

One afternoon, I meet an energetic New Yorker named Mark Christian, who runs the C-Spot, a ratings site for premium chocolate. Christian likes to talk about the “retro-chocolate revolution.” By retro he basically means the Maya, who revered cacao long before the invention of the Dutch process in the 19th century led to the industrial production of chocolate. That’s when chocolate became a standardized, inexpensive consumer good, rendered smoothly bland by sugar and vanilla. “Cacao went into the candy bin,” Christian says, “dumbed down with domesticity,” most of its “bandwidth of flavor removed.” A few decades ago, however, small makers, inspired by the world of wine, began to produce chocolate that tasted nothing like the Nestlé or Hershey’s of the grocery aisle.

Christian is on a passionate quest to restore the luster and magic of chocolate, to explain why terroir is as important for cacao as it is for grapes, to understand the genetics of the cacao plant, to patiently tell people why they should pay $12 for a bar. He lays down a bar of “Madagascar 72%” from a small California “barsmith,” Bar au Chocolat. I take a piece, letting it melt in my mouth, the preferred method. I resist the urge to say, “It’s good.” But I realize how much training my tongue—hardly a stranger to chocolate—needs. “This is very identifiable origin—the red island,” Christian says. “It’s often a very top-heavy origin, all of these upper-register fruit analogues but no real ballast. She’s processed it in a way where you get good symmetry between high and low.”

Christian knows about the dangers of fetishization, and he does not want to simply wrap chocolate in a shroud of empty luxury: a list of “banned words” on his website includes gourmet, sophisticated, and, yes, connoisseur. He is aware of the trap of being seduced by good packaging and by misinformation spread by supposed experts—for example, the prevailing opinion that darker chocolate is always better chocolate. Conspiratorially lowering his voice, Christian tells me: “I love white chocolate.” Most people “in the tribe” disdain it. “They grumble, ‘It’s not chocolate.’ ”

He pops a piece of white chocolate in his mouth, enthusing over “the way it stakes out a melting point that’s almost identical with your body temperature.” He sighs. “Just enjoy it, receive it.”