When I was growing up, Miloš Forman’s Amadeus always seemed to come on cable TV around Christmas. Something about the cinematography, I suppose, with those carriages rumbling over snowy Old World streets, made the film particularly suitable for wintertime viewing. The movie was a favorite of my family’s, and we watched it whenever it aired. Not that certain aspects didn’t bother me: Tom Hulce’s portrayal of Mozart as a crass, farting man-child always seemed more than a little preposterous. But how could a film with so much glorious music not leave an indelible impression? The scene depicting the composition of Mozart’s Requiem has always been a favorite: as the composer lay dying, sweat-stained and exhausted, he enlists the composer Antonio Salieri to help complete his final work. Those 10 minutes or so are both poignant and dramatic—but also, as I only later learned, a complete fiction.

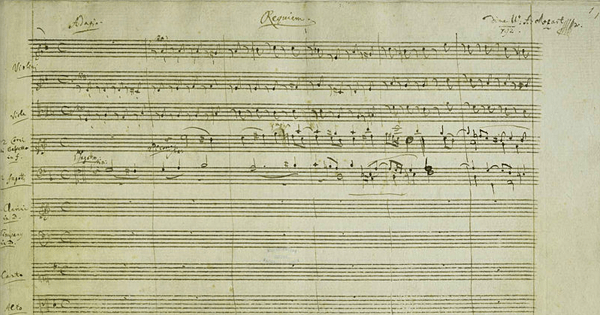

Neither Forman nor Peter Shaffer, whose 1979 play inspired the film, intended to produce a faithful biographical account of the composer. The movie is a work of art. If its historical basis is tenuous, any liberties it takes seem less important than its dramatic arc and richly drawn characterizations. As it turns out, Salieri was not some failed, embittered bachelor who commissioned the Requiem as part of a plot to bring about Mozart’s end. Neither was he Mozart’s amanuensis. The commission for a Requiem mass actually came from a young aristocrat named Count Franz von Walsegg, who wanted to memorialize his dead wife, Anna. Desperate for the handsome fee, Mozart accepted, but set the piece aside to work on his operas The Magic Flute and La clemenza di Tito. He managed only to complete the opening Introitus and Kyrie of the Requiem, though he did compose several other sections in a four-part vocal arrangement.

As Mozart’s health worsened, his wife, Constanze, asked the composer Joseph Leopold Eybler to help finish the work. Eybler scored a good bit of the Dies irae before giving up, frustrated perhaps by the lack of sketch material with which he had to work, daunted, more than likely, by the size of the task before him. In 1791, Mozart died. Constanze now approached a former student, the 25-year-old Franz Xaver Süssmayr, who gamely completed the piece, writing much of the concluding music himself. Other reconstructions have appeared over the years, yet Süssmayr’s is the version best known today and the one most often performed—even as scholars continue to revile it for its imperfections and clumsiness. Süssmayr was, by many accounts, a middling talent at best.

Yet what if we were to hear a version of Mozart’s Requiem that consisted only of music that the composer wrote? And what if this skeletal score were finished with music that had nothing to do, idiomatically, with Mozart? This was the project that Georg Friedrich Haas undertook more than a decade ago in writing his Sieben Klangräume, or Seven Soundspaces, an hour-long work that surrounds Mozart’s fragments with interludes that are decidedly 21st-century in temperament.

Originally from Vorarlberg, in the far west of Austria, and now a professor of music at Columbia, Haas is among the most important of contemporary composers, a master of innovative harmonic colors whose works occasionally inhabit the realm of performance art. His masterpiece, in vain, for example, which has engendered a cult-like devotion among new-music enthusiasts, requires that the audience be immersed in darkness for much of its duration. (Even to hear the piece via recording, I can attest, is a thrilling, frightening, and mesmeric experience.) Haas’s music makes uses of microtonal intervals—that is, intervals between two notes that are smaller than the semitone. In exploring the tension between pure tones and microtones, Haas builds upon the work of György Ligeti, who, in such pieces as Atmosphères and Lontano, summoned up immense and gauzy clouds of sound. The conductor Simon Rattle has talked of an “intergalactic stillness” when describing Haas’s scores, while also invoking the “throb and glow” of a Mark Rothko canvas. Part of this exquisite sound world comes from Haas’s obsession with the possibilities of timbre, the exploitation of overtones and other acoustical phenomena—techniques pioneered by the so-called spectral school of composers.

Now imagine seven soundspaces composed in such a style alternating with fragments of Mozart—and only those notes that Mozart composed, at that. (Therefore, no Sanctus, Benedictus, Agnus dei, or Lux aeterna.) Anyone familiar with Süssmayr’s reconstruction will immediately notice how naked these Mozart fragments sound, sometimes accompanied only by the basso continuo line of the organ, yet this austerity seems almost a necessary complement to Haas’s very contemporary soundspaces.

The first of these soundspaces follows the Dies irae: a swirling haze above the unsettling rumble of the chorus. Time and space appear at once to contract and expand as the music builds to a terrifying crescendo, before eventually dying away. The juxtaposition of styles can be jarring at first, but eventually, the two idioms slyly merge. After I had listened to Sieben Klangräume for the third or fourth time, Mozart’s Tuba mirum, featuring that expressive solo trombone line, began to sound as if it were specifically written as a prelude to the second soundspace, with its air of anxiety and confusion, the orchestral line falling and falling and never rising back up again, as if there were no bottom to the sonic abyss that Haas has created. With the chorus chanting, the music floats across our ken like a nebula in the cosmic night, shifting its shape menacingly.

A chilling moment comes after the fragment of the Lacrimosa. Mozart only wrote the first eight measures—eight slow-burning bars that ascend with increasing intensity, chorus, violin, and viola heading to an emotional climax. And then … nothing at all. Silence. Eventually, we hear the fifth soundspace, making out only the hushed sounds of percussion instruments, like soft exhales of breath, and the strings playing col legno, that is, with the wood of the bow striking the strings—a sound like rain. Or is it meant to be tears? The moment is all the more poignant when we know the text that has preceded it: “Mournful that day / when from the dust shall rise / Guilty man to be judged.”

One of Haas’s intentions, I think, is to show us how, until the day he died, Mozart was a man judged—not by his god, but by other men, none of whom had even a trace of the composer’s gift. Though the chorus in Haas’s soundspaces sings not one line of Latin, it does intone the text of a letter that Mozart received in the last year of his life, in response to his request for an unpaid position as assistant Kapellmeister of St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. The letter, in Haas’s words, sounds a note of “administrative brutality,” while showing “a total lack of understanding of everything related to art.” In the sixth soundspace, the chorus recites this document in full. It’s impossible not to feel a certain dread here as the voices relentlessly babble and chatter, hectoring the composer, reminding us of the bureaucratic realities Mozart had to endure. For any musician, having to beg for an unpaid job would be demeaning enough. But for the preeminent genius of the 18th century? Haas’s reliance on this letter brings another, more human, dimension to a work that has typically existed on a higher plane. It’s an ingenious effect. It also brings, in a way unimagined before, the fragments of Mozart’s death-soaked Requiem to life.