I have a weakness for tearjerkers from the 1940s, films featuring Dana Andrews and Teresa Wright, and drunk scenes that end not in calamity but in self-awareness or an act of courage. All of these elements are present in The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). You may want to have a handkerchief on hand for the wedding scene at the end. Two of the principal characters marry, two others plight their troth, a third pair blesses the scene with their presence, and Hoagy Carmichael plays “Here Comes the Bride” on the piano for a chorus of kids to sing along to.

Director William Wyler made a number of wonderful movies (Mrs. Miniver, Wuthering Heights), but this is an all-time great.

Three servicemen return to their small hometown after the end of hostilities in Europe and the Pacific in 1945. They represent the three primary divisions of military service and as many distinctions in socioeconomic class. Army sergeant Al Stephenson (Fredric March), a middle-aged man, holds an executive position at the local bank. In line for a promotion, Al is returning to his wife, Milly (Myrna Loy), and their two children, one of whom, Peggy (Teresa Wright), is old enough to witness a miserable couple and vow to “break that marriage up.”

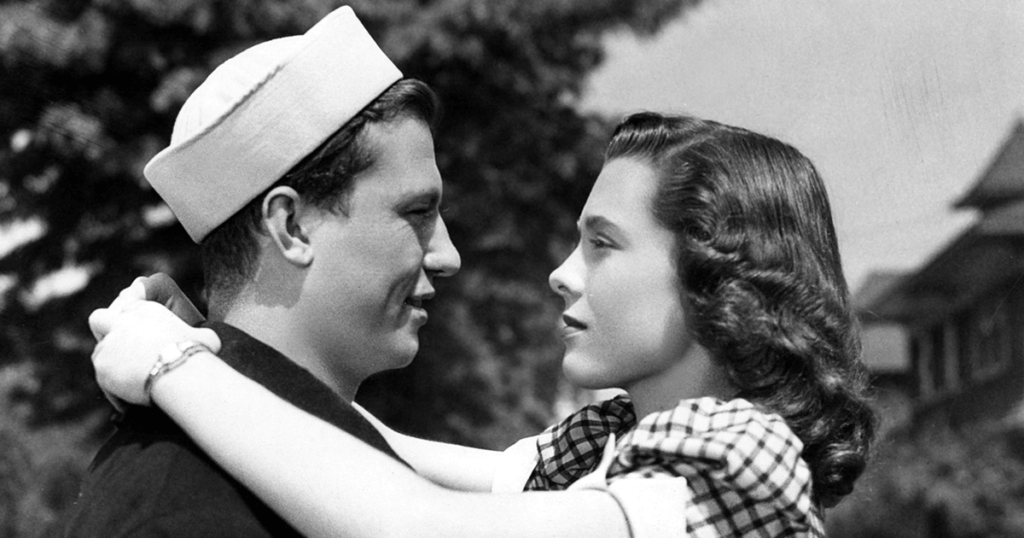

As for the younger men, Air Force hotshot Fred Derry (Dana Andrews) displayed valor under fire flying sorties over Europe, and now has nightmares of bombing raids and comrades who were shot down. Sailor Homer Parrish (Harold Russell), the youngest and lowest in rank, was a star quarterback in high school. But he will throw no more passes; he now has hooks for hands—as does Russell himself.

As an example of narrative brilliance, the movie’s presentation of the veterans’ first night back is hard to beat. Al has brought home souvenirs from the Pacific theater, but they seem to have lost their meaning on the living room table. When he, Milly, and Peggy go to celebrate at Butch’s, Butch (Hoagy Carmichael)—who happens to be Homer’s uncle—obligingly plays “Among My Souvenirs,” a marvelous song that a hungover Al will reprise in the shower the next morning. The integration of the song into the movie’s plot is exemplary.

Fred, who married Marie (Virginia Mayo) in an overnight romance before going overseas, joins the Stephensons that night at Butch’s because Marie is not at home and he doesn’t have the key to their apartment. The guys get plastered; Milly and Peggy are indulgent; and Fred ends up spending the night at the Stephensons’ apartment. When he cries out in his sleep, Peggy comforts him, and in the morning she makes him breakfast, foreshadowing a relationship to come.

The picture won its laurels as a sensitive treatment of the problems of returning service men. Courageous though he may be, Homer has taken quite a hit in the solar plexus of his self-esteem, and the awkwardness of people around him makes matters worse. Wilma (Cathy O’Donnell), his high school sweetheart, loves him, but it takes the better part of the movie for him to realize that her love really is “for better or for worse, in sickness or in health.”

The most affecting part of the story is Fred’s journey. A decorated Air Force hero who outranked Al in the military, Fred can’t get a job better than a soda jerk. He loses even that position when he slugs a smug customer who maintains that we fought the wrong foes in World War II and that Homer lost his hands for nothing. Between Fred and Marie there’s zero chemistry; she is stepping out on him and a divorce is inevitable. But Peggy’s folks are not exactly enthusiastic about her dalliance with a “slick” young fellow who happens to be hitched.

A great scene: lovesick Peggy confronts her parents, saying they can’t understand her because they “never had any trouble.” To which Milly responds, turning to Al: “We never had any trouble. How many times have I told you I hated you, and believed it in my heart? How many times have you said you were sick and tired of me, that we were all washed up? How many times have we had to fall in love all over again?”

I am always moved by a scene in which Fred climbs aboard a discarded bomber, his “office” during the war, which is now rusting in an aircraft boneyard. The scene has no words, just music, as Fred sits and stares into his turbulent past and blank future. This may be my favorite moment in the film, but there are others very nearly as affecting, including the one in which, at a formal dinner of bank officers and trustees, Al gulps down too many highballs but manages not to hiccup when he makes a speech that begins unsteadily but ends with eloquence.

The movie was a huge popular as well as critical success. There were detractors; there always are. James Baldwin felt it was “sentimental,” a fantasy. On the film’s release, The New York Times’s Bosley Crowther saluted the ensemble cast and felt the movie was a “beautiful and inspiring demonstration of human fortitude.” Most viewers concurred. The movie won nine Academy Awards, including a richly deserved Best Actor trophy for Fredric March.

For William Wyler, The Best Years of Our Lives was a highly personal movie. Like Fred Derry, he flew bombing missions in Europe and lost a friend who was shot down. Like Al Stephenson, he was middle-aged when he served. And like Homer Parrish, he came home with a wound that never healed (he lost hearing in one ear).

The last lines in the movie are spoken by Fred Derry to his bride-to-be in her stylish summer hat: “You know what it’ll be, don’t you, Peggy? It may take us years to get anywhere. We’ll have no money, no decent place to live. We’ll have to work, get kicked around.” Fred speaks in earnest, but the embrace and the tears of joy in Peggy’s eyes are all that matter.