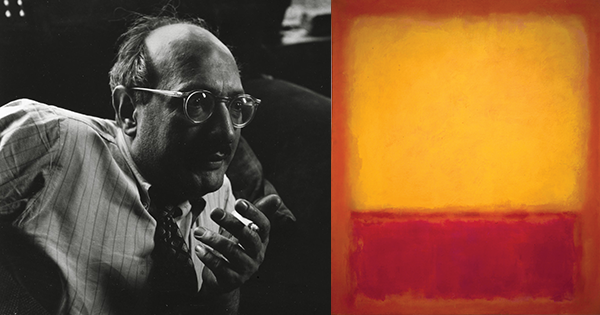

Mark Rothko: From the Inside Out by Christopher Rothko; Yale University Press, 302 pp., $35

Mark Rothko (1902–1970), whose paintings have mystified and entranced viewers for more than half a century, considered himself an extremely fortunate man. Now this good fortune includes a new book by his devoted son, whose collection of linked essays serves as a down-to-earth guide to (and guardian of) his father’s oeuvre. Like father, like son: both want art to speak for itself through form and color rather than narrative content, to aspire to the emotional power of instrumental music, to directly communicate universal truths.

Although Christopher Rothko is a practicing psychoanalyst as well as the custodian of his father’s estate, he generally refrains from the biographical approach to art, and he works to deflate readings of his father’s paintings that attempt to ground the artist’s inspiration in, say, his Jewishness or Latvian childhood. His own approach is implicit in his description of his father’s goals:

On the one hand, an objective stripping away of cultural and artistic clutter to get to the essential philosophical and pictorial elements, and on the other, a direct sensual communication of human emotion. The elemental ideas are generalized, abstract ones, not ones caught up in situational specificity. Similarly, the emotional plane is a universal one, not one beholden to individual experience.

Rothko’s ambitions for art were devout and extreme, and he would no doubt despise today’s art world for its quasi-sociological ironies and market-driven strategies, though his gently diplomatic son avoids stepping on too many toes. Christopher’s discretion is all the more admirable if one researches the trials he and his older sister went through after they were orphaned in 1970, which included a 10-year Dickensian legal battle against executors who had cheated them of their inheritance.

Rather, he keeps his eye on the prize, making his father’s work accessible and useful to those who, like me, have never been swept away. He is so successful in this that I, for one, am eager to go back and see, for instance, Rothko’s smaller works on paper, which the author defends against curators and potential buyers who consider them second class. Christopher argues that the later, darker work (produced between 1957 and 1970) also deserves careful and patient re-examination, or rather, re-immersion, although this is a harder sell. And we do benefit from such a loving and knowledgeable guide partly because, as with Tantric art, there is a cultural preparation necessary for breathing what can be rarefied air; for a long history precedes what aspires to be a self-sufficient experience. Christopher is aware that it takes effort to enter into this sphere, and that his father’s work may embody the end of a certain mindset about art and the world, all the while retaining a faith in the possibility of truth and the universal. Those of us who live in noisy specificity may find silent, resonant abstraction more of a curiosity than a monastic calling, but this book refrains from making us feel like Philistines: “My father, whom so many commentators seem determined to turn into a rabbi, is far more of a psychoanalyst, providing the obtrusive silence of the analytic hour; the silence you must fill with you.” We are told that “he was the philosopher who happened to paint,” looking for unity in an atomized world. There is reason to believe his faith in art’s power may have been shaken toward the end, but one feels nostalgic for this level of aspiration for art.

The take both the painter and his votary have on other artists and the other arts is intriguing. Rothko loved Piero della Francesco and disliked Mondrian, which is curious, since all three artists seem to consider painting a carefully crafted conduit to intuited truth. Rothko killed himself when Christopher was six, but they shared a passion for music, as described in one of the most charming and evocative chapters. Rothko admired, first and foremost, Mozart, identifying with an art that “smiled through tears,” and he was apparently less than sure about musical tributes to his own work in pieces such as American composer Morton Feldman’s quietly haunting Rothko Chapel. Equally revealing is the chapter on Rothko’s humor, which we become convinced is far from an oxymoron. In short, both Rothko and his son emerge as real mensches, men we might like to have as friends. I imagine that Christopher is a fine shrink: accessible, empathetic, and funny. Yes, he can be a curmudgeon, but a self-aware one, complaining at length about descriptions of his father’s paintings as “stacked.” But as a painter, I find that his approach to the work, as well as to the man, mostly rings true, as in this passage drawn from the book’s final page: “My father and I both believe at core that all people are ordinary, even the most accomplished. Sometimes, however, those very people are able to create things that transcend the ordinary, things that are greater than the fallible beings that created them.” Fallible Rothko was, but his son’s book stands as an affectionate and refreshing introduction to his troubled father’s best work.