Dr. Sal Mangione, a physician at Thomas Jefferson University, has a passionate interest in the works of Leonardo da Vinci, whose anatomical sketches he uses to instruct his medical students—and anyone else who is interested. I first heard him lecture on da Vinci at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, where he spoke to a rapt audience.

Mangione is striving to make a connection between Leonardo and Vesalius, the Flemish physician considered the father of modern anatomy. This year marks the 500th anniversary of the birth of Vesalius. It is also, Mangione points out, the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s last dissections. He did these for years, cutting the bodies himself and then sketching them in a basement room in Florence. Mangione believes that Leonardo’s great sketch of a fetus in the womb, part of his effort to discover the soul’s origin in the body, was the point at which the Catholic Church intervened. Forced to stop dissecting, he moved to France and died a few years later.

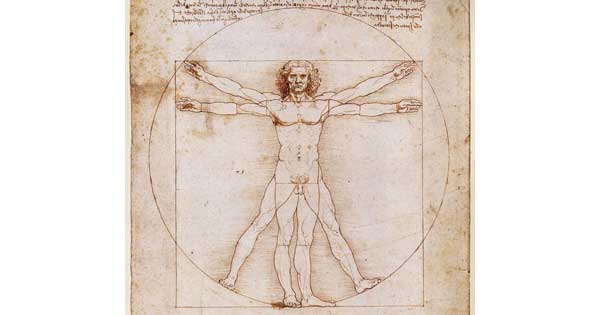

Mangione began his study of Leonardo with Vitruvian Man—that wonderful sketch that demonstrates the proportions of the human body (and whose face is possibly one of Leonardo’s many self-portraits). As Mangione sees it, the sketch marks Leonardo’s transition from outer to inner—from a focus on art to a focus on science. Subsequent sketches explore the inner workings of the body and pioneer representational techniques, such as multiple views, cross sections, and exploded views. Leonardo was the first to produce an accurate drawing of the human spine and to understand the structure and the hydraulics of the heart. He explored the muscles behind facial expression and performed comparative dissections of old and young bodies.

In their accuracy and mode of representation, these drawings were more than 100 years ahead of their time. Even so, Leonardo never published them, presumably unsatisfied with how they turned out.

On the relationship between Leonardo and Vesalius, Mangione writes: “there is almost a symbolic passage of the torch from the old Italian master to the brash Flemish upstart.” According to Mangione, Vesalius knew about Leonardo’s work, but in keeping with his narcissistic personality, never acknowledged the fact.

Whatever the degree of Leonardo’s influence on Vesalius, Mangione believes that, even after the march of centuries, Leonardo’s anatomical sketches have retained their currency. The technical information in them may no longer be a novelty, but they are testaments to the power of observation in the advancement of medical knowledge. Leonardo thought in pictures, and this, says Mangione, is the best way to learn about the body. His sketches are also works of sublime beauty, and, as such, pay tribute to that “piece of work” that is the human body.